At 06:15 on September 20th, 1944, Major Charles Carpenter crouched beside his Piper L4 Grasshopper on a muddy airirstrip near Aracord, France, watching fog roll across fields where German Panther tanks were advancing toward trapped American positions. 32 years old, 47 combat sorties, six bazookas bolted to his wings.

The German fifth panzer army had launched 262 tanks and assault guns against combat command A of the fourth armored division two days earlier. Carpenter was a high school history teacher from Molen, Illinois before the war. He taught teenagers about battles. Now he flew a fabric covered observation plane with a 65 horsepower engine over battles where men burned inside steel coffins.

The L4 Grasshopper weighed 765 lbs empty. Maximum payload was 232 pounds, assuming a pilot and no radio. Carpenter had mounted six M9 bazooka launchers on the wing struts. Each launcher weighed 15 lb. The M6 A3 heat rockets added another 3 lb each, 18 total rockets. The mathematics said his plane was overloaded by nearly 90 lb.

Every other L4 pilot in France flew reconnaissance missions. Spot enemy positions. Call coordinates to artillery. Stay high. Stay safe. The Germans barely bothered shooting at Cubs. Too small, too harmless. Carpenter had spent three months watching American tank crews die while he circled overhead with binoculars and a radio.

The fourth armored division lost 48 Shermans in the first two days at Aracort. German Panthers could penetrate Sherman armor at,200 yd. American 75mm guns needed 300 yd for a kill shot. Most Sherman crews never got close enough to fire. September 18th, the fog came before dawn and German tanks used it for cover. Carpenter took off at first light, but the ground disappeared beneath white nothing.

He circled blind for 90 minutes. By the time the fog lifted, 11 American Shermans were burning in the fields around Lonville. He watched crews bail out. Some made it, most did not. One Sherman took a hit to the ammunition storage. The explosion threw the turret 40 ft. Carpenter saw the loader stumble out with his uniform on fire.

The man took five steps and collapsed. Carpenter could do nothing except mark the position and call it in. September 19th. The 113th Panza Brigade pushed through American outposts near Arakor. 43 Panthers destroyed or damaged by midnight. American tankers fought from concealed positions using terrain and surprise.

It worked barely, but Combat Command A was spread thin across 12 mi of rolling farmland, and the Germans kept coming. Two weeks earlier, Carpenter heard about Lieutenant Harley Merrick and Lieutenant Roy Carson. They mounted bazookas on their L4s and destroyed two German trucks. Trucks. Carpenter wanted tanks. He found an ordinance tech and a crew chief willing to help.

They bolted three M9 launchers to each wing strut just outboard of the jury struts angled upward 20°. Electronic triggers wired to switches in the cockpit. Individual fire or full salvo. The crew chief named the plane Rosie the rocketer. Other pilots called it suicide. If you want to see whether Carpenters’s bazooka armed Grasshopper could actually destroy German tanks, please hit that like button.

It helps us share more forgotten stories from World War II. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Carpenter. The fabric on the L4’s wings was treated cotton. The bazooka rockets produced,200° of exhaust flame. Nobody knew if the wings would catch fire. Nobody knew if the overloaded grasshopper could pull out of a dive steep enough to aim the angled launchers.

Nobody had tested it in combat. September 20th, morning fog. German tanks attacking through the mist. Carpenter climbed into the cockpit alone. No observer, no radio operator, just him and 18 rockets. The engine coughed twice and caught. He released the brakes and the overloaded grasshopper lurched forward. By noon, he would either be dead or he would change how cubs fought.

The grasshopper climbed through fog at 400 ft per minute. Maximum climb rate was 600, but the extra weight cost performance. Carpenter leveled off at 1500 ft. White nothing below. White nothing ahead. He throttled back to cruising speed. 75 mph. The engine settled into a steady drone. Fuel capacity was 12 gallons.

Endurance roughly 3 hours. He had left at 0642. By 0930, the fog still had not lifted. The L4 handled differently with the bazookas mounted. The launchers created drag. The rockets added weight to the wings. Carpenter tested shallow banks. The grasshopper responded sluggishly. He pushed the nose down 5°. The fabric wings creaked.

The bazooka tubes caught wind and pulled. This was not the gentle cub he had flown on artillery spotting missions. This was something heavier, something angrier. At 0953, the fog began breaking apart in patches. Carpenter saw ground through gaps, fields, trees, the Rin Canal reflecting gray sky. He dropped to 1,000 ft and began a systematic search pattern, north to south, east to west, looking for German armor.

The fourth armored division’s combat command a held positions around Araort and the surrounding villages. Juval to the north, Monor to the south, Bzange Leapit to the east. German forces had attacked from multiple directions trying to encircle American units. Carpenter needed to find where they were massing for the next push.

11:07 The fog cleared enough to see the roads. Carpenter spotted movement. 3 mi northeast of Aracourt, he descended to 800 ft. Panther tanks. He counted six, maybe seven, difficult to tell, with some partially hidden in tree lines, armored cars moving with them, infantry following on foot. The formation was advancing southwest toward American positions. Carpenter checked his fuel.

Enough for one attack run and 90 minutes reserved to return to base. The M9 Bazooka had an effective range of 300 yd. The rockets traveled at 265 ft per second. Gravity and wind affected trajectory beyond 100 m. Carpenter needed to get close, very close. The bazookas were angled upward 20° from horizontal.

To aim them at a target on the ground, Carpenter had to put the grasshopper into a shallow dive, 30° nose down, maybe 35. aim with the entire aircraft, fire at 100 meters, pull up before German infantry opened fire with small arms. He climbed to,200 ft and positioned himself south of the German column, sun behind him. The Panthers were moving slowly through terrain, still partially obscured by ground fog.

Carpenter pushed the throttle forward and nosed over. The grasshopper accelerated in the dive. 80 mph. 90. The fabric wings vibrated. The bazooka tubes screamed in the wind. He could see individual panthers now. Turrets traversing, commanders standing in hatches. He armed the first launcher. Right-wing outboard position.

His thumb rested on the firing switch. 150 m. The lead panther grew larger in his windscreen. 120 m. He could see the German cross markings on the turret. 100 m. Carpenter pressed the switch. The M6 A3 rocket ignited with a crack that shook the entire airframe. 1,200° of exhaust flame shot backward, missing the fabric wing by inches.

The rocket stre toward the Panther, trailing white smoke. Carpenter did not wait to see impact. He hauled back on the stick and the grasshopper clawed for altitude. The overloaded plane responded slowly, too slowly. German infantry below opened fire. Small arms, machine pistols, rifle rounds snapped past the cockpit. One punched through the fabric on the left wing.

Another hit the tail section. Carpenter kept climbing. 200 ft. 300. The firing stopped. He leveled off at 800 ft and looked back. The Panther had stopped moving. Smoke rose from the engine deck. Not destroyed, immobilized. The rocket had hit the thinner armor on top or damaged the engine. The rest of the German column had scattered into defensive positions.

Infantry were pointing at the sky, at him. At the cub with bazookas that just attacked a Panther tank. Carpenter had 17 rockets remaining, and the Germans were no longer ignoring observation planes. Carpenter turned the Grasshopper northwest toward the American airirstrip at Lonville. Fuel gauge showed nine gallons remaining, enough for reloading and one more sorty, maybe two if he stayed over friendly territory.

The bullet holes in the wing and tail were small. The fabric held. The control surfaces responded normally. He descended to 100 ft and followed the terrain back to base using trees and ridges for cover. German infantry now knew cubs could bite. He touched down at 11:58. Ground crew ran to the plane before the propeller stopped turning.

They saw the bullet holes first. Then they saw the empty bazooka tube. One crew chief climbed onto the wing and examined where the rocket had fired. The fabric around the launcher was scorched black, but intact. No burnthrough. The metal tube had channeled most of the exhaust away from the wing surface.

The design worked barely. Reloading took 14 minutes. Six M6 A3 rockets slid into the launch tubes. Each rocket weighed 3.38 pounds. Total weight 19.4 in long. Blunted nose designed to prevent deflection at low impact angles. Shaped charge warhead could penetrate 3.5 to 4 in of armor plate. The crew chief asked what Carpenter hit.

One Panther immobilized. The crew chief asked how close he got. 100 m. The crew chief said that was insane. Carpenter said it was effective. 1219. Carpenter took off again. Fuel load 11.7 gall. Maximum capacity was 12 but ground crew could not completely fill tanks during rapid turnaround. 18 rockets total across both sorties. Six expended, 12 remaining.

He climbed to 1200 ft and turned east toward Araor. The fog had mostly cleared. Visibility extended to 5 m. German positions were now exposed to American air observation. Carpenter scanned for armor concentrations. 1241. He spotted another formation. Eight Panther tanks moving south along a tree line east of Bzange Laapit.

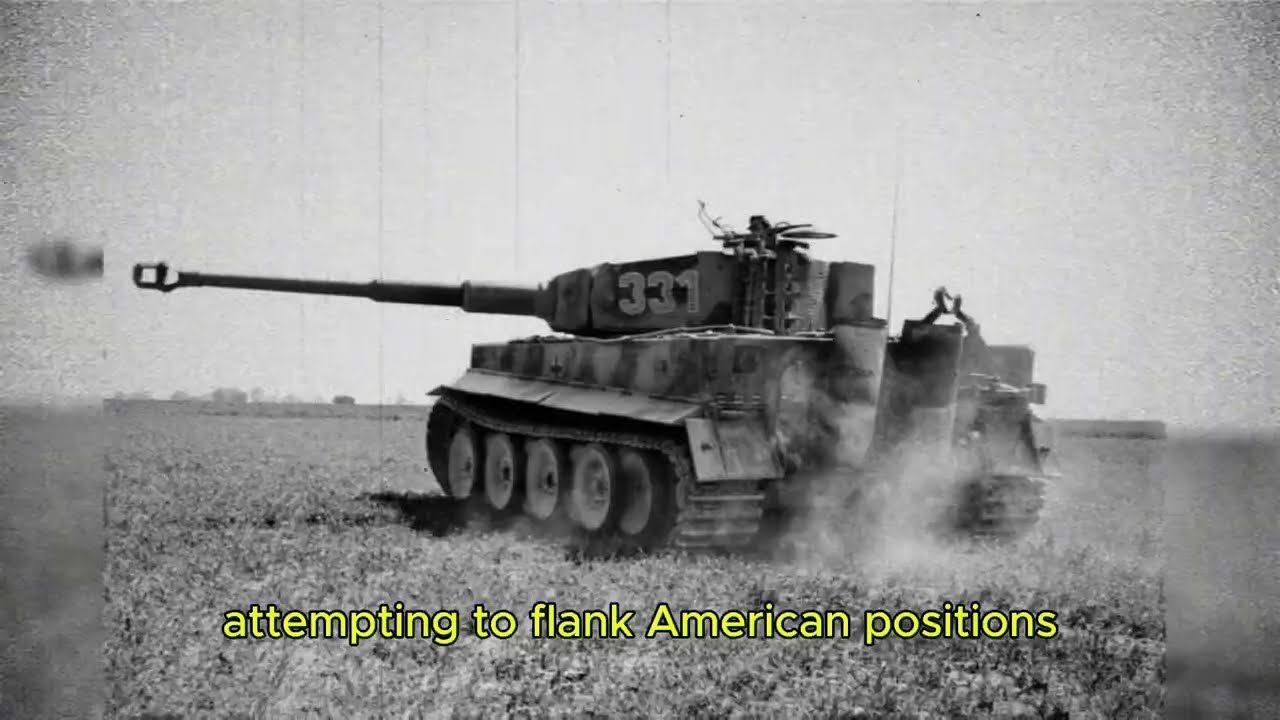

Infantry following in halftracks. This was a larger force than the first. Probably elements of the 111th Panzer Brigade attempting to flank American positions. Carpenter radioed coordinates to Combat Command A. Artillery, received acknowledgement, but artillery took time. Shells had to be ranged, adjusted, walked onto target.

The Panthers would be gone before rounds landed. Carpenter decided to attack immediately. He climbed to 1500 ft and positioned for a diving attack from the southwest. Sun still behind him. The Panthers were spread across 400 yd of road. Carpenter selected the lead tank. Same technique as before. Nose down 35°. Accelerate in the dive. 100 m range. Fire.

The first rocket launched clean. He pulled up hard and banked left. Machine gun fire followed him, heavier than before. The Germans had learned they were ready. Tracers arked past the cockpit. Something hit the engine cowling with a metallic clang. The Continental engine coughed once, but kept running. Carpenter circled wide at 1,000 ft and looked back.

The lead panther had stopped. Smoke from the engine compartment, immobilized, not destroyed. The rest of the formation scattered into dispersed positions. Infantry dismounted from halftracks. Some were setting up what looked like anti-aircraft positions. Carpenter had 11 rockets left, but the Germans were now actively hunting him.

He lined up for a second pass, dove toward a panther that had pulled off the road into a field, armed the launcher. 120 m. German infantry opened fire while he was still descending. The grasshopper shuddered. Fabric ripped somewhere behind him. He fired anyway. The rocket stre down. Carpenter pulled up without confirming impact. More tracers.

Something punched through the lower fuselage. He felt the impact through the rudder pedals. 800 ft. He leveled off and checked instruments. Oil pressure normal. Engine temperature normal. Controls responsive except the rudder felt mushy. He looked back. The second Panther was burning. Not immobilized. Destroyed. Flames poured from the turret hatches.

Crew bailing out. But Carpenter’s tail section had multiple tears in the fabric. One elevator cable looked frayed. The rudder was responding, but with noticeable delay. Two Panthers stopped, 10 rockets remaining. But his aircraft was damaged, and the Germans were setting up dedicated anti-aircraft positions around their remaining armor.

Carpenter turned west toward Lonville. The damaged rudder made coordinated turns difficult. He had to overcompensate with aileron inputs. The grasshopper wanted to slip sideways in banks. Fuel gauge showed 7.2 gall, enough to reach base with minimal reserve. The engine still ran smoothly, but the oil temperature had climbed 5° above normal.

Not critical yet, possibly a small leak from the round that hit the cowling. 1321. Radio transmission from Combat Command A. German armor had bypassed forward positions and trapped a fourth armored division waterpoint support crew 3 mi east of Araore. Approximately 20 men, no heavy weapons. Panther tanks closing on their position. Artillery could not reach them without hitting American forces.

Air support was engaged elsewhere. The Waterpoint crew was requesting immediate assistance. Any assistance. Carpenter checked his position. 4 miles from the trapped Americans, 6 miles from his airirstrip, 10 rockets remaining on a damaged aircraft that was barely holding together. The smart decision was obvious. Return to base. land.

Let me assess the damage. Reload. Return in a working aircraft. But the transmission said Panther tanks were closing on the position. 20 American soldiers had minutes, maybe less. He turned the Grasshopper east and pushed the throttle forward. The engine responded. Oil temperature climbed another 3°. Carpenter descended to 500 ft and followed terrain features toward the coordinates Combat Command A had transmitted. 1334.

He spotted the waterpoint position. Five trucks parked in a small clearing surrounded by trees. American soldiers visible, taking cover behind vehicles. Then he saw the Panthers, four of them advancing from the northeast, maybe 800 yd from the American position. Infantry moving with the tanks.

The Germans had learned from the previous attacks. When Carpenter approached, all four Panthers stopped moving. Infantry scattered into defensive positions. Machine guns traversed skyward. They were waiting for him, ready for him. This would not be a surprise attack against an unsuspecting column. This would be a gun battle where Carpenter was flying an unarmed observation plane made of fabric and hope.

He climbed to 18800 ft outside effective small arms range. Barely. The Panthers resumed advancing toward the trapped waterpoint crew. Carpenter had to choose. attack and probably get shot down or circle uselessly while 20 Americans died. His right hand moved to the firing switches. He armed all remaining launchers, 10 rockets. He would fire everything in successive passes and pray the grasshopper held together. First dive, 38° nose down.

The damaged rudder made the descent unstable. He had to fight the controls. 95 mph 100. The airframe vibrated badly. Something in the tail section was loose and rattling. Lead Panther filled his windscreen. German infantry opened fire at 200 m, far earlier than before. They had estimated his attack pattern. Tracers converged on his flight path.

150 m. Carpenter fired two rockets, both launchers. The Grasshopper bucked from the recoil. He pulled up hard. The elevator control cable frayed during the previous attack. Chose that moment to separate partially. The stick went mushy. Response delayed. Carpenter pulled harder. The nose came up slowly. Too slowly.

He was still below 400 ft when he passed over the German position. Rifle fire from every direction. The grasshopper shuddered. Multiple impacts. Fabric tearing. Metal pinging. He held the climb. 500 ft. 600. Both rockets hit near the lead panther. Near, not on. The explosions threw dirt and debris, but the tank kept moving.

Damage perhaps not stopped. Carpenter leveled off at 900 ft. The engine was running rough now. The oil temperature gauge showed red. Definitely a leak, maybe worse. His fuel gauge read 5.8 gall. Not enough to return to base if he stayed in the area much longer. The tail section felt like it might separate entirely. Eight rockets remaining.

Three Panthers still advancing on 20 trapped Americans. And the Germans below were no longer just shooting at him. They were coordinating. They were learning his attack pattern. They were waiting for him to dive again so they could kill him. Carpenter had 30 seconds to solve the problem. The Germans expected him to dive from altitude.

They positioned their guns to cover that approach. The Panthers kept moving toward the American waterpoint crew. 700 yd now. American soldiers were firing rifles at armored vehicles. Useless, desperate. Carpenter needed a different angle, a different pattern, something the Germans would not anticipate. He dropped to 200 ft.

Terrain following altitude below effective range of organized anti-aircraft fire. The Germans had positioned their guns skyward, expecting high dives. Carpenter approached from the west, using a tree line for concealment. 80 mph. The damaged elevator made level flight difficult. The engine temperature gauge stayed deep in the red zone, oil pressure dropping.

He had minutes before the Continental engine seized, 600 yd from the Panthers. Carpenter popped up to 300 ft and immediately nosed over into a steep dive. Attack angle 40 degrees, steeper than before. The angled bazookas meant steeper dives aimed more directly at targets. The lead panther was 200 yards from the trapped Americans.

Carpenter armed two launchers, leftwing, outboard and center positions. 130 m range. German infantry spotted him. They swung their weapons, but Carpenter was already firing. Both rockets launched simultaneously. The recoil nearly stalled the Grasshopper. He shoved the throttle to the stop and pulled back hard on the damaged elevator.

The nose came up barely. He cleared the Panther by 70 ft. Both rockets hit. One struck the turret ring. The other penetrated the thinner top armor of the engine compartment. The Panther stopped. Flames erupted from the engine deck. Crew hatches flew open. German tankers bailed out with their uniforms smoking. Destroyed. Confirmed. Destroyed.

Not immobilized. Burning. Carpenter did not climb. He stayed at 300 ft and immediately turned for the second Panther. The Germans were confused. Their anti-aircraft positions were aimed at empty sky above while Carpenter attacked from below their firing lanes. He armed two more launchers, right-wing outboard and center.

The second Panther was turning its turret toward the American waterpoint position. Range 110 m. Carpenter fired both rockets and banked hard right. Machine gun fire from German infantry ripped through the left wing. The fabric separated completely from the forward lift strut. The wing held together barely, but it held. One rocket missed.

The second hit the Panther’s turret side armor at a 30° angle. Penetration. The shape charge detonated inside. Secondary explosion followed. Ammunition storage cooking off. The turret lifted 6 in and settled crooked. Crew emergency exit through the bottom hatch. The Panther burned, two destroyed, two advancing. The remaining Panthers were 500 yards from the American position.

Infantry with them had gone to ground. Some were retreating. They had watched two Panthers die in 90 seconds. Carpenter armed two more rockets, six remaining total. The engine was shaking badly now. Metalon metal grinding sounds from the cowling. Temperature gauge pegged maximum. He had one more attack run before the engine failed completely.

Third dive. The rear Panther smaller target partially obscured by the lead tank. Range 120 m. Carpenter fired one rocket saved the others. The rocket hit low. Track assembly. The Panther slew left and stopped moving. Immobilized but not destroyed. The crew kept the engine running. turrets still traversing.

The last Panther was 400 yards from 20 American soldiers. Carpenter had five rockets and an engine that was seconds from catastrophic failure. Oil smoke poured from the cowling. The propeller was vibrating so badly he could barely see through it. The trapped waterpoint crew was firing everything they had at the advancing Panther.

Small arms, useless against armor. Carpenter turned the dying grasshopper toward the last German tank. The last Panther was 350 yardds from the American position. Close enough that Carpenter could see individual soldiers behind the waterpoint trucks. They had stopped firing, conserving ammunition, preparing for the tank to overrun them.

The Panthers turret traversed toward the largest truck, preparing to fire. High explosive round would kill everyone in the blast radius. Carpenter’s engine seized for two seconds. The propeller stopped. Complete silence except for wind through the torn fabric wings. Then the engine caught again, grinding, clattering, dying, but not dead.

Not yet. He armed three rockets, everything remaining on the right wing. He would fire all three simultaneously. Maximum firepower. One pass. No second chances. The Grasshopper descended to 150 ft. lowest attack altitude yet. The Panther was stationary now, hauled down behind a slight rise, only the turret visible to the Americans, but Carpenter was coming from the side from the east.

He could see the full hull profile. Thinner side armor compared to frontal plate. Range 140 m. The damaged elevator barely responded. Carpenter used throttle and aileron to aim the entire shaking aircraft. 120 m. The Panthers commander stood in the turret hatch, scanning for threats. He saw the Grasshopper. Too late.

Carpenter fired all three rockets. The simultaneous launch nearly tore the right wing off. The Grasshopper rolled violently left from the unbalanced recoil. Carpenter fought the controls. The wing held. The rockets converged on the Panther. All three hit within two seconds. First rocket struck the turret side, penetration.

Second rocket hit the upper hull, penetration. Third rocket hit the track assembly and detonated externally. The combined effect was catastrophic. The Panther’s ammunition storage exploded. The entire vehicle lifted off the ground from internal pressure. Turrets separated completely. The hull split open. Secondary explosions continued for 15 seconds.

Nobody escaped. Four Panthers, two destroyed, two immobilized, 20 American soldiers alive. The Waterpoint crew was already moving, loading trucks, preparing to evacuate while German infantry was still scattered and disorganized. Carpenter had saved them, but his aircraft was 3 mi from base with an engine that had approximately 60 seconds of life remaining.

He turned west. Maximum power. The engine responded with sounds no Continental 0170-3 should ever make. Metal fragments rattled inside the cowling. Oil covered the windscreen. Temperature gauge had stopped reading entirely, probably broken, definitely overheated. The propeller continued turning through momentum and desperation.

2 mi from Lonville. The engine seized again. This time it did not restart. Complete silence. No engine, just wind. The Grasshopper became a glider. A very poor glider with torn fabric and a loaded weight distribution never designed for unpowered flight. Carpenter trimmed for best glide speed, 65 mph. Altitude 800 ft.

Descent rate approximately 400 ft per minute. He had 2 minutes of gliding time, maybe less with the damaged aerodynamics. 1 mile from the airrip. Altitude 400 ft. Carpenter could see the runway. Ground crew had spotted him. They could see the oil smoke, the torn wings. They were clearing the runway. Fire equipment moving into position. He was too low.

The glide angle would not reach the runway. He needed another 200 ft of altitude. He did not have 200 ft. There was a field northeast of the runway. Plowed earth, soft ground. Bad for landing gear, but better than trees. Carpenter aimed for the field. Altitude 150 ft. The grasshopper descended steadily.

No engine power to arrest the sink rate. No control authority at low speed with damaged surfaces. 100 ft. The field expanded below him. 50 ft. He pulled back gently on the stick, flared the landing. The tail wheel touched first, then the main gear. The soft earth grabbed the wheels. The grasshopper nosed over. The propeller dug into mud.

The aircraft flipped forward and came to rest, inverted. Carpenter hung upside down in his harness. Fuel was leaking from the ruptured tank. The engine was hot enough to ignite gasoline vapor. He had seconds to escape before Rosie the rocketer burned. Carpenter released his harness. He dropped onto the inverted cockpit roof. Fuel dripped onto his flight suit.

The smell of high octane gasoline filled the enclosed space. He kicked at the side door, jammed. The impact had bent the frame. He braced his back against the seat and kicked harder. The door broke free. Carpenter crawled out through the opening, rolled clear, got to his feet, ran 20 yard before his legs gave out.

Ground crew reached him 40 seconds later. Fire equipment sprayed foam on Rosie the rocketer. The fuel leak stopped burning before ignition occurred. Medical personnel checked Carpenter for injuries. Minor cuts. Bruises across his chest from the harness. No broken bones, no burns. 47 combat sordies in bazooka cubs, never wounded.

The ground crew called him the lucky major. Carpenter called it mathematics. Stay low. Attack fast. Never give them a clear shot. September 20th, 1944. Three sordies, 18 rockets expended. Four Panther tanks stopped. Two destroyed. Two immobilized. 20 American soldiers extracted alive. One L4H Grasshopper destroyed.

Engine seized from sustained oil loss and thermal damage. Wings torn beyond repair. Fuselage structurally compromised. Total writeoff. But the concept worked. Bazookas mounted on observation aircraft could kill tanks. The fourth armored division’s combat command a held arcort against the German fifth panzer army counteroffensive. Between September 18th and September 29th, German forces committed 262 tanks and assault guns to recapturing Lonville and eliminating the American bridge head.

They lost 200 destroyed or damaged. American forces lost 48 tanks. The battle of Aricort became the largest tank engagement on the Western Front until the Battle of the Bulge 3 months later. Carpenter’s bazooka attacks on September 20th disrupted German coordination during critical hours when combat command A was most vulnerable. Carpenter received another L4H 3 days later. Serial number 43-30426.

Same modifications. Six M9 bazookas. Same crew chief. same name painted on the cowling, Rosie the Rocketer. Between September and December 1944, Carpenter flew 63 more bazooka attack missions. Official records credited him with six tanks destroyed total, two Tiger tanks, four Panthers or Panzer 4s, several armored cars, numerous soft skinned vehicles.

Witness accounts from ground forces suggested the actual number was higher, possibly 14 tanks. difficult to confirm when Carpenter attacked targets miles from American lines and could not land to verify kills. Other L4 pilots attempted similar modifications. Most abandoned the concept after one mission, diving a fabriccovered observation plane into concentrated anti-aircraft fire was statistically unservivable.

Lieutenant Harley Merrick and Lieutenant Roy Carson, the original Bazooka innovators, returned to standard reconnaissance duties after destroying their two trucks. They concluded the risk outweighed the tactical benefit. Carpenter disagreed. He attacked German armor 63 more times after September 20th.

The Stars and Stripes newspaper interviewed him in October. Asked why he continued. Carpenter said the war needed to be fought 60 minutes an hour and 24 hours a day. Attack, attack, attack again. German forces changed their doctrine because of him. Before September, they ignored Cubs. Observation planes were not threats. After Carpenter, standing orders required all ground units to engage any L4 on site.

Infantry carried dedicated anti-aircraft weapons when operating with armor. Panther and Tiger commanders posted spotters specifically to watch for cubs with tubes on their wings. The Germans called him Deer Varuka Major, the Mad Major. Carpenter accepted the name. said madness was required when fighting tanks that could kill Shermans at 1,200 yards.

The fourth armored division advanced east through France. Carpenter flew with them. Personal pilot for General John S. Wood in addition to his attack missions. By December, Third Army had pushed to the German border. Carpenter had accumulated 110 combat sorties, still never wounded despite being shot at during every bazooka attack.

Then 1945 arrived and Carpenter became ill. Doctors diagnosed Hodgkins disease in early 1945. Lymphoma terminal. Army physicians gave Carpenter 2 years maximum survival time. He was 32 years old. He had survived 110 combat sorties flying an unarmed observation plane into anti-aircraft fire. Never wounded, never shot down by enemy action.

Cancer would accomplish what German Panther tanks could not. The Army promoted Carpenter to Lieutenant Colonel and awarded him the Silver Star for Valor, bronze star with oakleaf cluster, air metal with oakleaf cluster, officially credited with six tanks destroyed, 17 armored vehicles disabled or destroyed, dozens of soft-skinned targets.

The citations mentioned extraordinary heroism and complete disregard for personal safety. They did not mention that Carpenter was a high school history teacher who believed wars should be fought aggressively or not at all. June 1946, honorable discharge. Carpenter returned to Urbana, Illinois. Returned to teaching, back to classrooms and teenagers and lessons about battles he had lived through.

His wife, Elda, had waited. His daughter Carol was 7 years old. Carpenter had two years according to military doctors. He intended to spend them teaching. 1948 arrived. Carpenter was still alive, still teaching. 1950, still alive. 1955, still alive. The 2-year prognosis became 5 years, then 10, then 15. Medical science in the 1940s did not fully understand Hodgkins disease progression.

Some patients exceeded predicted survival times. Carpenter became one of them. He taught history at Urbana High School for 20 years after doctors said he would be dead. March 22nd, 1966, Charles Carpenter died at age 53, 21 years after diagnosis, 19 years past the predicted 2-year survival.

He outlasted the cancer almost as stubbornly as he had attacked German tanks. Buried at Edgington Cemetery in Illinois. The grave marker listed his rank, Lieutenant Colonel. It did not mention Bazooka Charlie or Rosie the Rocketer or the Mad Major, just the name and dates and service. The L4H Grasshopper Carpenter Fle serial number 4330426 disappeared after the war.

Most assumed it was scrapped or lost. In 2017, aviation historians identified the aircraft in the collection of the Austrian Aviation Museum at Grod’s airport. It had been flying in a civilian club in Vienna for decades. Nobody knew its history. Nobody knew it was Rosie the rocketer. The Collings Foundation purchased the aircraft in 2018 and began restoration.

The same grasshopper that destroyed Panther tanks in September 1944 would fly again. Carpenters’s innovation did not survive the war. The L4 with bazookas was too vulnerable for sustained combat operations. Helicopters eventually replaced observation planes. Dedicated ground attack aircraft replaced improvised weapon systems.

But for 4 months in 1944, when American tank crews were dying against superior German armor, a history teacher from Illinois flew a 65 horsepower observation plane into anti-aircraft fire because somebody had to do something. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button.

Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about pilots who saved lives with bazookas and courage. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from.

Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Charles Carpenter doesn’t disappear into silence.

These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that