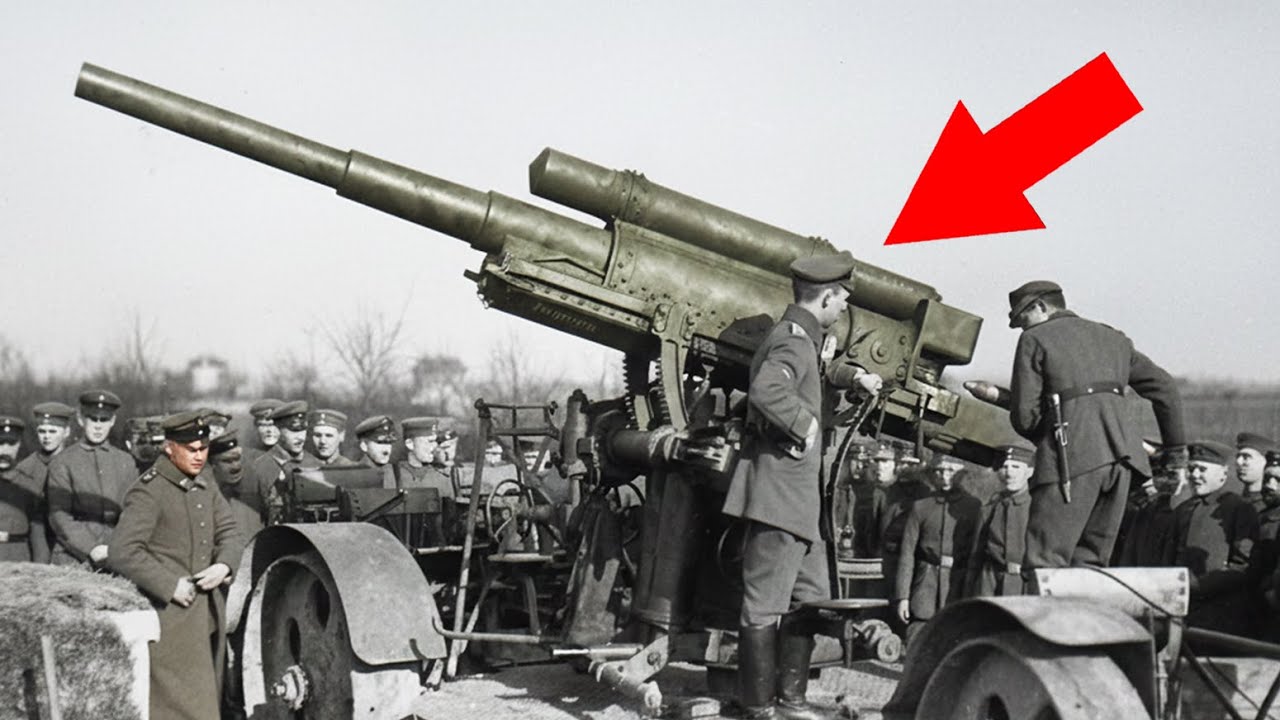

This is the 8.8 cm flack gun. A weapon built to fight the sky, yet feared most on the ground. Its shells tore through armor at distances other guns could barely reach. Its recoil shook the earth. Its accuracy forced entire armored units to rethink how they advanced. If you were standing beside the crew right now, feeling the shock waves slam through your chest, smelling the burning metal ahead, you would understand why this gun became a legend.

and why serving behind it demanded more than courage. It demanded acceptance of the cost. Its journey began long before these tanks exploded. And that journey is where our story starts. In the early years of the 1930s, Germany moved in shadows. The Treaty of Versailles still limited its weapons. Yet, many leaders believed another conflict was coming.

Factories that were supposed to build tractors quietly shifted toward military parts. Designers met in hidden rooms. Engineers worked under false names. All of this was meant to rebuild an army that officially was not allowed to exist. Among the projects pushed forward in secret was a new type of cannon meant to fight enemies that could not be reached from the ground.

High-flying bombers. Aviation had changed quickly after the First World War. Aircraft were no longer slow. Fragile machines that barely cross trenches. Bombers grew stronger each year. They could carry larger payloads, climb higher into the sky, and travel far beyond the protection of ground troops.

Many military thinkers feared these new planes more than tanks or infantry. They imagined a single formation wiping out a city block in minutes. Engineers were asked to create a gun that could throw a shell high enough, fast enough, and accurately enough to stop these aircraft before they released their bombs. The task fell to Croo, a company known for building heavy weapons.

At first, the work moved slowly. Designers struggled to balance weight, accuracy, and durability. Some early prototypes vibrated so hard that the barrels cracked. Others could not rotate fast enough to follow a plane moving across the sky. Each failure taught the team something new, but each failure also reminded them of the scale of what they were trying to stop.

If bombers reached German cities without resistance, the consequences would be devastating. Gradually, a new shape formed on the drawing boards. It was a long barreled cannon with a smooth recoil system and a clever four-legged carriage that allowed it to turn in any direction. The design team focused on power.

They increased the barrel length to push shells at extremely high speed. They strengthened the brereech to handle larger propellant charges. They added elevation controls so the gun could point almost straight upward. Every piece served a single purpose. place a timed fuse shell in the path of a fast, distant aircraft. When the first completed model stood on the test range, it did not look like the famous weapon it would later become.

It looked unfamiliar, almost oversized. But the engineers felt a sense of early confidence. They tested it against targets hung from balloons, then against moving dummies. They learned how quickly the barrel could heat and how often parts needed to be changed. After each round of trials, more adjustments followed.

The team refined the gunnery sights, strengthened the carriage legs, and reworked mechanical controls. Each improvement brought the gun closer to the reliability needed for war. By the middle of the decade, the cannon earned its official designation, the 8.8 cm flak 18. The name sounded simple, but inside military circles, it signaled something important.

It meant Germany now possessed a high velocity anti-aircraft weapon built for a future conflict many suspected, but few admitted publicly. Crews began training with it in isolated fields far from major cities. Commanders taught them how to work as a team around the heavy weapon. 10 men learned to load, aim, measure distance, and set fuses while listening to orders shouted from a central director.

Every movement demanded speed. Every mistake meant the difference between hitting a bomber or watching it pass overhead. As the training expanded, the government increased investment. Factories produced more barrels, carriages, and specialized tools. New units formed across the country. Many officers believed the gun would remain mostly a deterrent, something to discourage enemy air forces from flying too close.

Even fewer imagined how exposed crews would become when using a cannon large enough to be seen from miles away. The first hint of its potential arrived sooner than expected. Germany sent a small number of FLAC 18 guns to Spain during the civil war to support its allies. The purpose was not only political but also practical.

Designers needed real combat data and Spain offered it. there. The gun showed capabilities that surprised both sides. The high velocity rounds not only threatened aircraft, but also tore through bunkers and lightly armored vehicles. Crews learned the gun could switch between targets quickly because of its rotating carriage.

They also learned how visible they became when firing. Dust clouds, bright muzzle flashes, and tall silhouettes made every battery a tempting target for artillery and opposing aircraft. The weapon was powerful, flexible, and accurate. Yet, the men who operated it faced immediate danger whenever a battle intensified.

Officers praised its destructive ability, but remarked on the high risks crews endured. These lessons shaped future tactics, but they also pointed toward a darker truth. A large gun that could be seen from the air would eventually attract fire from bombers, fighters, tanks, and infantry. They had no armor, no turret, and no cover except shallow trenches hastily dug around the platform.

Back in Germany, high command studied these lessons and requested more improvements. Engineers introduced better sights, stronger barrels, and a carriage that could be deployed faster. The gun evolved rapidly, but so did the scale of the war that approached. Production increased dramatically. training schools filled with soldiers learning how to handle timed fuses, rangefinders, and heavy ammunition.

Yet, beneath the technical progress was a growing sense of urgency. European tensions rose, conflicts heated, and almost everyone inside the Luftwaffer understood that if war broke out. By the late 1930s, the flack 18 had become a symbol of modern air defense. It stood at airfields, near factories, and along coastline positions.

Crews practiced night and day, tracking imaginary targets across the sky. Nobody yet realized how long those barrels would remain hot or how many crews would fall beside them. The weapon was ready. The crews were trained. What they could not see was that the future held battles far larger than the designers had imagined. The skies of Europe were about to become the most dangerous front of the war, and the men behind the guns would pay the highest price for holding them.

When the first shipment of 8.8 cm guns reached Spain during the Civil War, the crews who accompanied them carried more curiosity than confidence. Many of these men had trained only in calm fields back in Germany, where the sky was quiet and the range officers controlled every moment. In Spain, the air felt different. Dust hung in the heat.

The sound of distant fighting drifted through the hills. The atmosphere itself seemed to warn that this would be the place where the gun revealed its true nature. For the first time since its creation, the new cannon stood on real soil, shaped by real conflict. The weapon was placed on ridges overlooking battle zones where aircraft and armored columns moved unpredictably.

Crews learned quickly that nothing stayed still for long. One moment the enemy attacked from the air and the next they surged across open ground. The 88 had been designed for high-flying bombers. Yet combat rarely followed expectations. When planes appeared, the men swung the long barrel upward.

When armored trucks or fortified pockets resisted the advance of Allied forces, the gun lowered again, ready to fire at ground targets. These rapid changes forced crews to adapt faster than their training had prepared them for. As the days passed, Spanish observers reported how the shells behaved when fired across long distances.

The rounds reached targets with surprising speed, and the accuracy impressed even seasoned commanders. The blast from each shot sent a wave of heat across the operating crew. Dust circles rose around the carriage legs. spent casings scattered across the earth in glowing arcs. Each time the breach snapped open, it gave off a sharp metallic sound that echoed against the valley walls.

These sensory details became part of the rhythm of daily operations, reminding the men that they were controlling a machine built for more than just one purpose. The gun proved effective against aircraft, but its real shock came when crews discovered how easily it dismantled bunkers and armored vehicles.

Tanks of the period carried only modest armor, so the high velocity shells tore through them with terrifying force. Reports described armored plates bending backward like thin metal sheets and turrets thrown open by delayed fuses. These observations reached Germany quickly. Engineers felt both pride and unease. Their anti-aircraft weapon had become a multi-roll tool, but this versatility meant crews would face far greater danger in future wars.

Combat in Spain also exposed a truth that training grounds never showed. When the 88 fired, it gave away its position instantly. The flash of the muzzle, the smoke cloud, and the silhouette of the long barrel created an unmistakable signature visible from far away. Artillery crews used this information to target the gun.

Enemy aircraft learned to search for these bright flashes to direct strafing runs. Even infantry began recognizing the outline of the carriage legs on ridgeel lines. Once spotted, the crew needed to shift positions or risk being hit before they could reload. Many units dug shallow pits around the gun, but these offered limited protection.

The cannon was too large, too open, and too demanding to operate behind heavy cover. Some crews experienced bombardments shortly after engaging enemy aircraft. High explosive shells landed near the gun, shaking loose dirt and fragments that wounded operators who were still adjusting sights or handling ammunition. The vulnerability of working in the open became difficult to ignore.

Although the 88 carried a small shield to deflect shrapnel, it covered only a narrow front arc. Anyone stepping slightly aside for a better angle lost that protection. Still, the crews continued their work because the weapon was needed, and the pace of the conflict offered little time for hesitation.

Despite these dangers, the Spanish campaign taught German officers valuable lessons and smaller anti-aircraft weapons. They observed how quickly the gun could shift roles during fluid battles. They measured the stress placed on barrels after long bombardments and adjusted maintenance schedules. They refined transport procedures so the gun could be moved in smaller windows of time.

Each discovery helped improve tactics that would later shape doctrine across the German army and air defense system. The experience also influenced technological upgrades. Rangefinders were improved so crews could track aircraft more accurately. Fuse setting equipment was redesigned to reduce mistakes during rushed engagements.

Carriage stability was strengthened to handle continuous firing. Little by little, the gun evolved from its first version into a more reliable and more lethal instrument. The changes did not erase its weaknesses, but they helped balance power, speed, and survivability. Each shell weighed heavily, and crews handled dozens during a single engagement.

The cannon demanded constant attention. Elevation controls needed adjusting. Fuse timers required careful setting. Ammunition had to be carried from crates to breach in a fast, steady rhythm. The level of focus needed during combat left many operators mentally drained after every mission. For some, fatigue increased mistakes, and mistakes could be fatal when handling explosives.

After several months, German officers concluded that the weapon was too valuable to remain limited to anti-aircraft roles. Its unexpected effectiveness against ground armor meant it might be required in situations far beyond what its designers imagined. The lessons from Spain convinced the high command to increase production and prepare more units for possible deployment across Europe.

The crews who survived those early battles carried home knowledge shaped not by theories but by the harsh reality of fire and steel. Their reports spread through training schools where new groups of soldiers studied every detail. The 88 had proven itself and the stage was set for a larger conflict. The world around Germany moved closer to war each month and military planners knew that the skies would become battlegrounds on a scale far beyond anything the Spanish campaign had seen.

No one yet understood how large the struggle would become or how many crews would eventually fall beside the guns they served. But the first hints were already visible. Spain had been the rehearsal. Europe would soon become the main stage. When the war finally erupted across Europe in 1939, the 8.8 cm gun was no longer an experiment or a foreign test piece.

It stood in hundreds of positions across Germany, Poland, and soon the rest of the occupied territories. Factories had increased production. Training grounds turned into full regiments. crews who once practiced with empty skies above them now faced the real possibility that bomber formations could appear at any moment.

At the start of the conflict, Allied air power was still developing, but this would change rapidly as the fighting intensified. The gun that had proven itself in Spain was now part of a much larger and much more complex defense network. German air superiority made it rare for enemy planes to survive long enough to reach targets deep in German-h held areas.

A battery might spend several days waiting for an air raid that never arrived. In those moments, the guns were directed toward other tasks, such as supporting infantry attacks or breaking through fortified lines. Crews learned to switch between roles with little notice, just as they had in Spain. But now the scale of operations was greater.

A gun positioned near a village one day could be forced to relocate by dawn. As the war expanded into Western Europe, Luftwaffer dominance allowed ground forces to advance quickly. Many flat crews traveled with armored divisions to protect columns from sudden raids. They rode on halftracks, trucks, or horsedrawn wagons depending on the region. Mobility became essential.

The 88 was heavy, but its carriage design made it surprisingly adaptable to movement. Every time the gun was redeployed, crews exposed themselves to stray fire and enemy scouts who looked for opportunities to strike before positions were established. Yet, the early months remained favorable for Germany, and crews operated with a sense of controlled danger rather than constant fear.

This balance shifted drastically when the first large-scale Allied bombing operations targeted German cities. Britain and later the United States launched raids that grew in size and frequency. The clouds above industrial areas became pathways for hundreds of aircraft at a time. The night sky filled with the drone of engines and the glow of burning buildings.

It became clear that the 88 seconds primary purpose had arrived. Crews who had once waited patiently in silence now spent entire nights firing shell after shell into the dark. The introduction of advanced fire control systems transformed how flack batteries worked. Large analog computers sat in reinforced bunkers near gun positions. These machines connected with rangefinders, sound detectors, and later radar units.

Data flowed to the guns through thick cables. Instead of each crew estimating altitude and speed on their own, the central command calculated interception points and transmitted them directly. This allowed several guns to aim at the same target simultaneously. Crews worked like parts of a larger machine, adjusting elevation wheels, setting fuses, and loading rounds with movements that had been drilled into muscle memory.

Even with better coordination, hitting a bomber was never simple. Aircraft flew at high altitude and moved quickly. Crews needed to fire not at the plane itself, but at a point ahead of it, where the shell would explode after climbing for many seconds. A small mistake in timing or angle meant missing the formation entirely.

The Germans still relied mostly on timed fuses, which required precise adjustments in the seconds before each round entered the brereech. Under stress, with the sky roaring and explosions shaking the ground, small errors became common. Yet, the guns continued firing because every missed shot still created a barrier of steel fragments that bombers had to pass through as raids grew heavier.

The skies turned into an arena where both sides suffered punishing losses. Bomber crews described the fear of watching black clouds of flax surround their aircraft. German flat crews described the same fear from below as bombs dropped toward their positions. Many batteries fought in exposed areas, often on rooftops, factory grounds, or open fields where a direct hit meant instant destruction.

The 88 seconds explosive muzzle flash made each gun an easy target for the bombers overhead. Even when the crews dug trenches or built sandbag walls, they remained vulnerable to collapsing soil and flying debris. The danger increased during daylight raids. Fighter bombers accompanying the large formations attacked gun positions with cannons and rockets.

Crews often found themselves switching between firing at the bombers above and ducking to avoid strafing runs that swept low over the fields. Ammunition carriers, fuse setters, and sight operators had to move in the open, making them easy targets for any aircraft searching for vulnerable ground teams. Over time, the noise, vibration, and danger eroded morale.

Even seasoned operators admitted that prolonged engagements made them feel as if the sky was collapsing. By 1942 and 1943, the pressure on flack units reached a breaking point. Germany’s industrial centers became primary targets. The Rur, Hamburg, and Berlin faced continuous raids. Some nights, batteries fired until their barrels glowed with heat.

Crews wrapped cloth around their hands because the metal controls burned their skin. Ammunition trucks lined the roads as fast as they emptied their loads. Engineers replaced barrels more frequently than ever. Yet, despite all this effort, the bombers returned the next night and the night after that.

As accuracy improved for the Allies and new tactics emerged, the flat crews found themselves at even greater risk. Some bombers released specialized fragmentation bombs designed to explode above gun positions. Others used flares to illuminate defensive areas. Radar jamming disrupted the German fire control network, forcing crews to rely more on visual estimation.

With limited visibility and increased stress, mistakes grew more frequent and casualties followed. The system that had once given Germany early confidence now struggled under the weight of constant attacks. By the end of this period, the sky could no longer be seen as a distant threat. It had become the most active front of the war, one where crews lived and died in moments shaped by noise, smoke, and blinding flashes.

Each raid left new scars on the landscape and the men who defended it. And yet, this was only half the story. As the ground war expanded and enemy armor grew stronger, the 88 would soon face a new challenge. One that forced crews to fight not only above them, but directly across the field in front of them.

As the war pushed into new regions, the role of the 8.8 cm gun changed in ways few had expected during its early development. The cannon had been created to protect the airspace above Germany. Yet events on the ground forced crews to lower the long barrel and face threats rolling toward them instead of flying overhead.

During the campaigns in France and later in North Africa, German forces encountered enemy tanks with armor thicker than anything seen in Spain. Many frontline anti-tank guns were too small to penetrate this new protection. Crews tried the standard 37 mm and 50 mm weapons, but the shells often bounced off, leaving only scorch marks.

In these moments, commanders began ordering the 88 seconds into direct line of sight battles, where accuracy and raw power mattered more than altitude or timing. The first major example came early in the French campaign. Thickly armored British and French vehicles resisted German fire, pushing forward across fields the defenders thought they controlled.

When lighter guns failed, officers directed 88 crews to reposition with urgency. The long barrels, usually angled toward the sky, now pointed across open terrain. The shift was dramatic. A gun meant to fire at distant aircraft, was now aimed directly at steel giants approaching through the smoke. Crews watched enemy tanks halt abruptly, their tracks broken or turrets blown open as the rounds tore through them.

This immediate effect caught the attention of many German commanders who realized the gun had far more potential than anyone had predicted. North Africa provided an even clearer stage for the 88 seconds evolution. The wide open deserts created long firing lines. Enemy tanks approached across sunlit planes with little cover, giving the German crews both time and visibility.

The guns long range became a powerful advantage. At distances where other weapons failed to reach, the 88 could still deliver accurate fire. Tanks that attempted flanking movements often found themselves exposed to longrange shells that struck with immense force. German units began integrating the gun directly into armored divisions, placing it behind tanks or near defensive ridges to catch approaching vehicles in deadly crossfire.

This strategy allowed smaller German forces to hold ground against larger Allied formations. But this new role came with extreme danger for the crew. When the 88 was used as an anti-aircraft gun, it usually operated from deep defensive positions. When used as an anti-tank weapon, it was placed much closer to the fighting. Crews now had to operate under the threat of enemy tank shells, machine gun bursts, and artillery fire.

Unlike a tank, the gun had no protective armor, and the small frontal shield offered minimal safety. To fire effectively, the crew needed to remain in the open, moving ammunition, adjusting sights, and operating controls while enemy fire landed all around them. If tanks advanced faster than expected, the crew often had only moments to decide whether to stay and fire or abandon the position.

The battles on the Eastern Front intensified these risks. When German forces encountered Soviet armor, especially early models with thick, sloped plates, the smaller anti-tank guns, became nearly useless at a distance. Crews dug shallow pits or hid behind farm buildings, but these improvised defenses rarely held against the chaos of battle.

Soviet tank units advanced in large numbers, often supported by infantry and artillery. When an 88 opened fire, it could destroy several vehicles in rapid succession. Yet its position became obvious to every enemy soldier nearby. Crews learned that each successful hit increased the likelihood that return fire would come immediately. Many gun positions were destroyed only minutes after opening fire.

The effectiveness of the 88 in these battles encouraged Germany to rethink its armored doctrine. Engineers developed new tanks and tank destroyers using improved versions of the gun. These machines brought the firepower of the 88 into armored shells that protected their crews. Yet, the original towed guns remained essential.

They were easier to produce in large numbers, simpler to transport, and already familiar to thousands of soldiers. Even as powerful, turreted tanks entered the battle, the Toad 88 continued to anchor many defensive lines across Europe. Operating the gun on the ground placed immense physical and mental strain on the crews.

The weapon was heavy, and moving it under combat conditions required coordinated teamwork. Ammunition boxes weighed enough to slow even the strongest men. During long battles, crews became drenched in sweat and dirt as they worked to keep the gun loaded and ready. The sound of incoming shells, the sight of advancing tanks, and the pressure to fire accurately created an environment where mistakes could mean death.

Despite these challenges, many crews developed remarkable skill. Experienced operators could hit distant targets with surprising precision, even while under heavy fire. As the war dragged on, the enemy improved their tactics. Allied tank crews learned to maneuver more cautiously, using smoke screens and dispersed formations to avoid becoming easy targets.

They also coordinated more closely with artillery, directing fire onto suspected 88 positions. Long before tanks approached, crews used netting, branches, and sandbags. But these methods only worked until the first shot revealed their location. The muzzle flash remained a glaring weakness, and once spotted, the gun often faced overwhelming retaliation.

By the middle years of the conflict, the 88 had earned a fearsome reputation among Allied tank crews. Many described the weapon as one of the most dangerous threats on the battlefield. Stories spread quickly of tanks destroyed at long distances where few expected enemy fire to reach. The more effective the gun became, the more aggressively the allies targeted it.

In many battles, entire crews fell before firing more than a few rounds. Survivors carried the memory of shattered positions, destroyed equipment, and friends lost beside them. The transformation of the 88 from anti-aircraft weapon to tank killer shaped the direction of the war on land. It allowed German forces to hold ground longer than expected and to challenge armored advances that might otherwise have broken through.

But this evolution also placed crews directly in the line of some of the most intense and deadly fighting. The weapons power brought both advantage and vulnerability. As the war continued to shift, these crews would soon face a new chapter where the skies and the ground became equally dangerous and the number of surviving operators began to fall sharply.

By the time the war reached its middle years, the balance of power in the air had shifted completely. What had once been a battlefield shaped by German initiative now turned into a constant struggle to survive. Waves of Allied bombers arriving day and night. Industrial centers that powered the German war machine became prime targets.

Entire regions lived under the sound of distant engines, knowing it signaled destruction moving toward them. For the flat crews, this shift marked the beginning of the most dangerous period they would ever face. It pressed down on every position, filling each hour with tension.

Large-scale raids grew in size until they filled entire horizons. British night bombers created long strings of red and white lights moving across the dark like floating cities in formation. Each wave carried hundreds of aircraft and many brought fighter escorts ready to attack any ground position that revealed itself.

Against this massive force, the flack guns fired constantly, trying to create a barrier of explosions thick enough to push the bombers away or tear holes in their formations. Crews felt the pressure rise as every mist burst meant more bombs falling onto the cities behind them. The work became exhausting. A gun that once fired several rounds in a single engagement now had to fire hundreds, sometimes thousands, during prolonged raids.

The metal on the barrel heated so intensely that it glowed orange. Crews wrapped cloth around elevation wheels and controls to avoid burning their hands. Ammunition haulers ran back and forth with crates twice their weight, moving quickly despite the cold or the rubble underfoot. Fuse setters worked with trembling fingers as explosions shook the ground.

The gears of the gun clicked, the brereech slammed, and the recoil slammed back into the carriage repeatedly, turning each minute into a test of endurance. Even with the advanced fire control network, accuracy suffered under stress. Bombers used radar jamming devices that disrupted calculations. Flares dropped from aircraft created false illumination that confused observers.

Some raids released long strips of metal foil that scattered in the wind, reflecting radar signals and filling screens with noise. Rangefinders struggled to lock onto targets, and crews often had to fall back on experience rather than clear instructions. Crews fought not only aircraft, but also the fog of electronic warfare that hid the enemy in plain sight.

Allied air forces soon understood how effective the 88 remained, and they adjusted their plans to destroy these guns whenever possible. Some bombers carried fragmentation bombs designed specifically to target anti-aircraft sites. These bombs released thousands of steel shards above the gun positions, shredding crews even if the shells did not hit directly.

Fighter bombers flew low, strafing with cannons and rockets. The roar of engines diving toward the ground became one of the most feared sounds for flack operators. Many positions suffered casualties before they could even load the first shell. The danger extended far beyond direct attacks.

Bombers dropped high explosive loads on factories, rail yards, and city centers. Many flack batteries were placed near these valuable targets, meaning crews often stood close to the impact zone. Buildings collapsed under their own weight. Fires spread across industrial districts, and shock waves shattered windows across entire neighborhoods.

Even if the gun survived, the crew had to fight through smoke, debris, and reduced visibility. Some batteries found themselves buried in dust, clouds so thick they could barely see their own weapon. Yet the firing continued because the sky still held enemy aircraft. As casualties increased, the Luftwaffer needed replacements.

Experienced crews became rare. Younger men, often still teenagers, joined the ranks to fill empty positions. Many came from the Hitler youth or from schools evacuated from cities. They learned quickly because the situation gave them little choice. Some were assigned to fuse setting stations or ammunition handling parties.

Others were placed on the elevation wheels or behind the brereech trying to mirror the movements of older soldiers. Their hands shook not only from the cold but from the knowledge that the survival rate for their role was one of the lowest in the entire German military. Women also entered the flack units primarily as spotters, communications operators, and radar assistants.

They worked alongside men to track bombers, calculate firing solutions, and direct batteries. Though they rarely handled the gun itself, they were exposed to many of the same dangers. Bombs did not discriminate between positions. A single hit on a command post or radar station could wipe out dozens of trained personnel in an instant.

As the raids intensified, communication centers became high priority targets for Allied aircraft trying to disrupt the defensive network. In some cities, the ground shook so frequently from explosions that many crews slept beside their guns, unwilling to move far from their posts. Tunnels and basement offered only partial protection.

The constant alarm signals, the glow of burning districts, and the fear that the next raid might destroy an entire battery left marks on the men. Fatigue caused accidents. Some mishandled fuses, others dropped shells during loading. A few collapsed from exhaustion, unable to continue. The mental pressure built as each night brought new losses.

By late 1943 and into 1944, the survival rate for many flat crews plummeted. Units posted near strategic points such as oil refineries, rail hubs, or submarine pens faced the highest risk. These positions were attacked relentlessly because their destruction weakened Germany’s ability to sustain the war. Flat crews stood between these targets and the bombers.

Each time they fired, they revealed their location, and each time they revealed themselves, they increased the likelihood of incoming fire. Some batteries were wiped out completely. Others lost crew members faster than they could be replaced. The collapse of the skies marked a turning point. The once strong and organized anti-aircraft network now faced an unstoppable force.

Yet, even under nearless conditions, crews continued to operate their guns. They followed orders, adjusted the sights, loaded the shells, and watched the sky fill with glowing tracer streams and dark clouds of bursting flack. Their determination slowed the devastation, but the cost grew heavier each month. What came next would push these units even further as the final year of the war brought the construction of massive flack towers and desperate last stands inside cities already collapsing under fire. As the war entered its final year,

Germany faced a reality that many leaders had refused to accept. Allied air power now reached deep into every major city. Industries burned, transportation networks collapsed, and large areas lay in ruins. The anti-aircraft network, once stretched across thousands of positions, was weakened by losses, shortages, and constant pressure from raids.

In response, the German high command relied more heavily on a series of massive concrete structures known as flack towers. These buildings stood like silent giants above the cities, offering both heavy firepower and protection for civilians who sought shelter inside. Their walls were made of thick reinforced concrete, strong enough to resist direct hits from heavy bombs.

Each tower had several levels, including ammunition rooms, command centers, hospitals, and living quarters. On the roof stood the large guns, often including the powerful 12.8 cm dual mounts supported by 88 mm cannons and smaller automatic weapons. When a raid began, the towers woke to life. Crews sprinted up staircases, spotter teams activated radar units, and operators prepared firing data while civilians hurried into underground sections.

The entire structure functioned like a vertical warship anchored inside the city. For many flat crews, being assigned to a tower was seen as a mix of luck and burden. On one hand, the walls offered far greater protection than open air positions scattered across industrial zones. On the other hand, towers became obvious targets.

Bomber groups often marked them on maps because they represented some of the most concentrated anti-aircraft firepower available to the Germans. As raids intensified, these towers found themselves facing waves of attacks designed to overwhelm their guns. Each tower had only a handful of cannons. Yet, the number of aircraft approaching sometimes reached hundreds.

Crews had to rely on discipline, careful aim, and coordination to create defensive fire that could disrupt the incoming formations. The firing experience at top a tower differed sharply from ground positions. The guns stood high above city streets, giving operators a clear view of the sky.

When shells detonated, the sound bounced against the concrete walls and echoed across entire districts. The recoil shook the roof, sending vibrations through the structure. Powder smoke drifted down stairwells. Warm brass casings rolled across metal grates. Inside the tower, pressure waves from explosions, rattled lamps, shelves, and loose equipment.

Civilians waiting below described the experience as standing inside a thunderstorm made of steel and fire. Despite the tower’s strength, the crews were still exposed. They worked in open air on the top platform where wind, cold, and shrapnel posed constant danger. When Allied bombers targeted the towers directly, the hits often cracked external concrete or shook the roof violently.

Operators had to hold their positions even as dust fell from overhead beams and alarms signaled structural damage. Because the guns were essential for city defense, withdraw orders were rarely given. Most crews stayed at their posts until ammunition ran low or equipment became unusable. As Allied armies advanced on the ground, the role of the towers expanded.

They were not only anti-aircraft platforms, but also strongholds meant to slow the enemy’s approach into the cities. In Berlin and Vienna, the towers housed thousands of civilians who had nowhere else to go. Families slept in long corridors while medical teams treated injured residents in makeshift clinics. The sound of anti-aircraft fire above mixed with the distant rumble of artillery outside the city.

For many people, the towers became the last safe place during the final battles. Their work did not only protect factories or military bases. It shielded desperate people hiding beneath their feet. As supplies dwindled, conditions grew more difficult. Ammunition shipments became irregular. Food and medical supplies ran short.

Engineers who normally maintained the guns were now busy repairing damage caused by constant raids or ground shelling. Some crews rotated between long firing shifts and emergency repair duties. Others slept beside the weapons using spare cloth or empty crates as makeshift bedding. Many struggled with exhaustion, knowing that if the towers fell, thousands of civilians inside would be left unprotected.

During the final battles for Berlin, the towers became some of the last structures still functioning. Ground fighting reached the outskirts of the city, and Soviet artillery targeted anything resembling a defensive strong point. Crews on the towers fired at aircraft, tanks, and infantry using whatever ammunition remained.

Some guns malfunctioned after months of continuous use, but operators worked around broken parts, adjusting firing angles manually or switching to backup weapons. The sound of urban combat echoed across the rooftops. Smoke rose from burning districts. The towers, once symbols of air defense, now stood as isolated islands surrounded by chaos.

When surrender finally came, surviving crews emerged into cities transformed by fire and destruction. Many walked down from the towers with their uniforms covered in dust and oil, carrying the memories of months spent fighting without pause. They had served through some of the most dangerous conditions experienced by any branch of the German military.

A large percentage of anti-aircraft personnel had been killed in action, often while defending positions that offered little protection. The toll was especially high among young replacements who entered service late in the war. In the aftermath, the towers remained as concrete reminders of the final stand. Some were partially demolished in the years that followed, while others became museums or storage facilities.

Visitors walking through the empty rooms could still see signs of the past. thick walls marked by shrapnel, narrow hallways that once held families during raids, and steel mounts where the guns once stood. The echoes of those final battles lingered in the air, a quiet testament to the crews who defended the skies until there was nothing left to defend.

The story of the flack units ended not with victory or clear resolution, but with survival and memory. Their work had slowed destruction, but could not stop the collapse of a war already lost. What remained was the understanding that these crews, standing beneath vast walls of concrete or beside exposed open field guns, faced dangers few other soldiers experienced.

Their casualty rate reflected the harsh reality of a front where the enemy came from above, from ahead, and often from all directions at once.