In wartime, food is never just food. By the winter of 1944, as the Second World War entered its final and most desperate phase, hunger had become a constant companion for millions across Europe. Ration cards grew thinner. Portions shrank. Entire cities learned to survive on substitutes and scraps. For many Germans, the war was no longer fought for victory, but for calories.

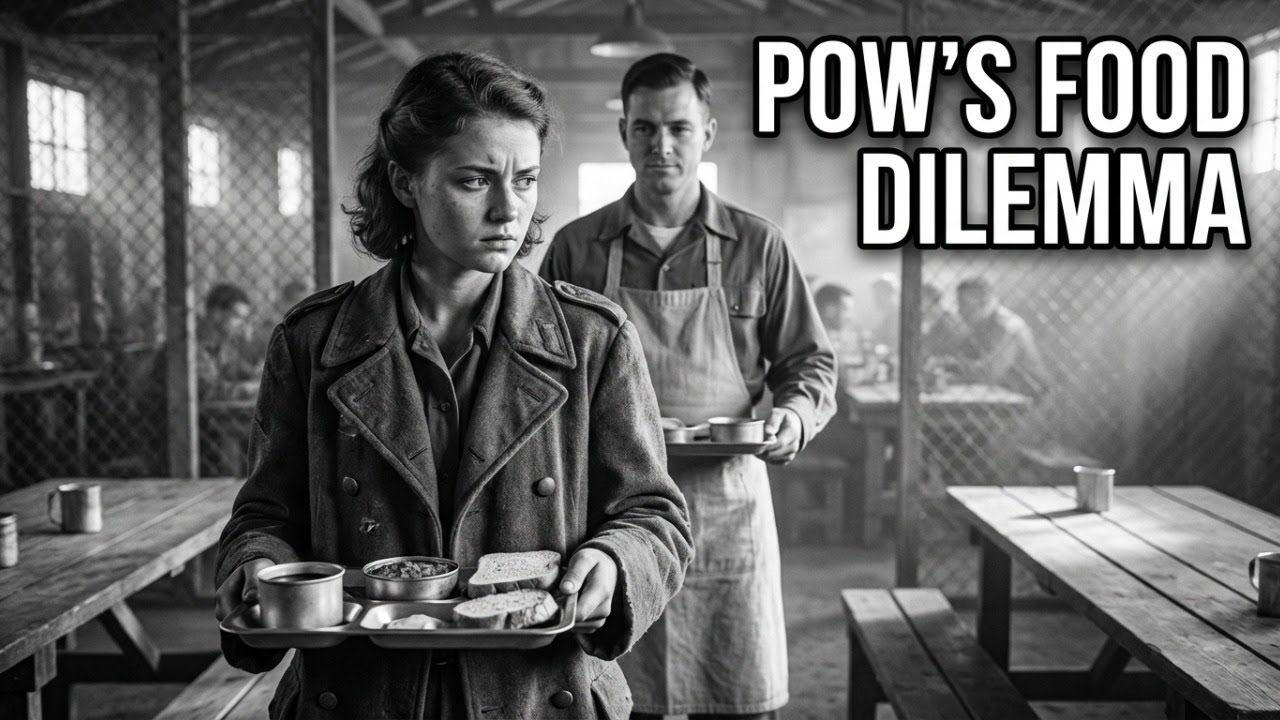

Far from the front lines, in a prisoner of war camp on American soil, a small group of German women carried that hunger with them. They arrived believing captivity would mean deprivation. They believed it would be punishment. What they encountered instead would quietly reshape how they understood the enemy and themselves.

One women in captivity. The presence of German women in Allied P camps was unusual but not unheard of. Most were auxiliary personnel, radio operators, clerks, medical assistants captured during the rapid Allied advances of 1944. They were not trained for captivity. Many had never left Germany before the war.

Now they found themselves thousands of miles away, surrounded by unfamiliar language, customs, and climate. Their greatest fear was simple. Would they be fed? Rumors followed them from camp to camp. American food, they were told, was artificial, sweet, unhealthy, not real food at all. Nazi propaganda had spent years portraying Americans as uncultured and careless people who ate poorly and lived without discipline.

The women repeated those stories to one another, partly to reassure themselves that what lay ahead could not possibly be worse than home. Two, the camp routine life in the camp settled into a predictable rhythm. Morning roll calls, assigned duties, long hours of waiting. The guards were firm but distant. They did not shout. They did not insult.

Meals were regular, too regular. Bread appeared every day. Meat appeared more often than any of the women could remember. At first, they ate cautiously, suspicious that the portions would soon shrink. They never did. Still, trust did not come easily. Hunger teaches skepticism. In wartime Germany, nothing generous was without consequence.

Three, an unfamiliar smell. One afternoon, something changed. As the women moved about the compound, a smell drifted through the air, warm, savory, unfamiliar. It did not resemble soup or boiled vegetables. It was richer, heavier. The women paused. “What is that?” one whispered. Another shrugged. Probably for the guards.

Food smells had taught them caution. In Europe, such smells usually meant food meant for someone else. But the aroma grew stronger and then they saw something unexpected near the women’s section of the camp. American cooks were setting up a serving table for them. Four suspicion at the serving line when the trays were uncovered. Confusion spread.

The food was unlike anything they recognized. Long smooth sausages placed inside soft bread rolls. No casing. No visible spices. No familiar shape. The women stared. That can’t be meat. One said quietly. Another shook her head. They wouldn’t serve this to prisoners. No one stepped forward. The guards waited patiently. No one hurried them.

One cook smiled and said something casual through an interpreter. Lunch was ready. The silence stretched. Finally, one woman spoke aloud what the others were thinking. You expect us to eat this? Five. The first bite. Someone had to decide. One of the women, young, thin, a former communications clerk, stepped out of line.

She lifted the unfamiliar food carefully, inspecting it as if it might explain itself. She smelled it. Nothing happened. Slowly, she took a small bite. For a moment, her face showed no expression at all. Then she swallowed. “It’s good,” she said, surprised by her own voice. A few guards exchanged glances. Someone chuckled softly. The tension broke, not with cheers, but with quiet relief.

Six a shift in the camp once the first woman ate. The others followed hesitantly at first than more freely. Some liked the bread. Some found the flavor strange but satisfying. Others laughed at the mustard, unsure what to make of it. Questions followed. Is this common food? Do Americans eat this often? One guard shrugged. More than we should, he replied.

It was not a grand moment. No speeches were made. No rules changed. But something subtle shifted. The women realized they were not being tested, not being mocked, not being punished. They were being fed what the guards themselves ate. Seven. What the meal meant, that realization stayed. For women who had lived under constant suspicion and propaganda, the meal carried a message more powerful than words.

The Americans were not trying to break them. They were not starving them. They were not proving superiority through cruelty. They were offering normality. In the weeks that followed, the story was retold quietly among prisoners and guards alike. It became a small legend of the camp, not because of the food itself, but because of what it represented.

Trust once cracked does not break loudly. It dissolves eight. The memory that lasted years later, former prisoners would recall that day not as a turning point of the war, but as a turning point in belief. It did not erase loss. It did not undo the past, but it challenged the idea that enemies must always be inhuman.

In war, ideology is built on distance. Distance between people, between truths, sometimes that distance collapses in unexpected ways. Sometimes it collapses over a shared meal. Because even in a prison camp, even in the middle of a global war, a simple act can remind both sides of something easily forgotten. That people are still people.

And sometimes the smallest moments carry the longest echoes.