This Doctor Discovered an Injured Bigfoot in the Forest – He Kept It Alive for 15 Years in Secret

Three Knocks in the Rain

My name is Daniel Carr. I’m 63 now, retired ER doc out of Olympia. It’s January 2025, and I’m sitting in my little rental outside Aberdeen, Washington. It’s cold rain, Pacific Northwest kind of rain, the kind that hangs in the air. I shouldn’t be telling this, but it’s been fifteen years.

Back in October 2010, Olympic National Forest, I went on a solo camping trip to clear my head after we lost a kid in trauma. Ordinary weekend. Coffee on the tailgate, wet pine smell, nothing special. Then sometime past midnight, I heard this breathing.

.

.

.

Not an animal I knew. Slow, ragged, like a big man with a punctured lung. I know what people think when they hear Bigfoot. I keep a clip on an old phone in a drawer. I’m not going to show you. I just need to say out loud what I did to keep that Bigfoot alive.

The baseboard heater ticks in the corner. The refrigerator hums. You can hear the highway in the distance like a slow river of tires on wet asphalt.

I still do the same thing every night. Check the deadbolt twice, then the back door, then the side gate. Old habit from those fifteen years. I tell myself it’s just leftover anxiety, not anything to do with what happened back then. I hate even using that word. Bigfoot. It sounds like a joke. I spent my whole life believing in charts, labs, clean evidence. X-rays don’t lie. Blood work doesn’t lie. But people lie all the time about what they saw in the woods.

Back then, when people in Olympia would talk about it on late night AM radio, I’d roll my eyes. The nurses would laugh about callers saying they saw Bigfoot near the Nisqually. I’d say, “If one comes into my ER, I’ll believe it.” The heater kicks off. The house goes quiet, heavy, and somewhere under that quiet, I swear I still hear those three distant knocks.

My wife Sarah used to ask why I jumped at sounds. She’d say, “Dan, you see gunshot wounds every shift. Why does a branch on the window make you freeze?” I never told her. By the time I could have, we were already separating over something else entirely.

The rain picks up outside. I listen to it drum on the gutters the way it did that October weekend when everything normal ended. I was 48 then. Good doctor, decent husband, rational. I voted, paid taxes, changed my own oil. I didn’t believe in conspiracy theories or lake monsters or anything you couldn’t put under a microscope. I especially didn’t believe in Bigfoot—until I found one dying in a ravine with a bullet through his leg.

Late October 2010, Graves Creek Campground sits about fifteen miles up a forest service road from the Quinault Ranger Station. The kind of place where cell service dies two miles before you arrive. Crickets, river noise, a little hiss from my camp stove, the kind of damp cold that creeps up through your boots. The lantern threw a soft amber circle and beyond that, just black trees leaning in.

There were only two other campers that Friday night. One was a retired logger named Bill in an old RV. He wandered over with a beer and started in on local stories. Cougar sightings, elk on the road, a hiker who went missing in ’08 and turned up three ridges over. No memory of how he got there. Then he said it casual as anything. “Some folks say there’s Bigfoot out this way. Whole troop of them.”

I snorted because I was still that guy. “If a Bigfoot breaks his leg, they’ll bring him to me. Until then, I’m not buying it.” He just shrugged and poked the fire. The smoke smelled like wet cedar. “Suit yourself, Doc. But people hear things. Three knocks in the dark. Always three.”

I asked what that meant. He said it was how they talked to each other. Signal. Warning. “You hear three knocks—something big is watching you.” I laughed it off, finished my coffee, watched the fire die down to coals.

Much later, after he went back to his RV, I lay in my tent listening to the river, telling myself the heavy footsteps I heard in the gravel were just Bill taking a late night leak. Then came three slow knocks on a tree way out in the dark, spaced five seconds apart. I told myself it was a branch falling. Wind. Anything but what Bill had just described.

My heart didn’t believe me. It hammered against my ribs until dawn.

Morning came gray and low. Mist hanging between the trunks. The forest smelled like wet earth and cold metal—that iron scent you get with blood in an ER. My boots crunched on frosty leaves. I wasn’t looking for anything. I was just walking. Coffee in a metal mug, steam fogging my glasses. About half a mile from camp, I saw a smear of dark red on a sword fern. Then more on a rock, like something big had stumbled through.

First thought: elk. Hunter must have got sloppy with the kill. I followed because that’s what I do. You see blood, you track it, you help if you can. The deeper I went, the quieter it got. No birds. No wind. Just my breathing and the occasional drip off the cedar boughs. The blood trail was steady, not spurting. Venous, not arterial. Whatever it was had time.

I told myself again that all those stories from the night before were in my head. But the prints beside the blood weren’t elk. They were huge, bare, human-shaped. I knelt by one, filling with muddy water, longer than my boot by half, toes clearly defined. No claw marks. I actually said it out loud, standing there alone: “This is not Bigfoot. This is a prank.” But the blood was real. The smell was real. Wet fur, heavy musk, something wild and hurt.

I kept walking. The trail led downhill into a ravine choked with salal and deadfall. That’s where the sound started—low, pained breathing, ragged human rhythm, but too deep, too slow. Every part of me wanted to turn back. Instead, I pushed through the brush, following the blood, my hands shaking so bad I spilled the last of my coffee.

I wish I’d stopped right there. Called the ranger. Let someone else find what I was about to find. But I didn’t. I found him.

Wind moved the treetops, but down in the ravine it was still. No birds. Just the distant rush of the river and a wet, labored breathing that sounded too big for anything I knew. He was half-hidden in salal and fallen branches. I won’t describe him fully. It still doesn’t sit right. Just large, dark hair matted with blood, chest rising shallow, one leg twisted wrong, and eyes—brown, human eyes—glassy with shock, watching me.

My first thought wasn’t Bigfoot. It was gunshot wound. There was an ugly lateral tear along the thigh. Meat and hair burned at the edges. High-powered rifle, I guessed. Probably hunters mistaking him for a bear in low light.

I don’t know what you are, I whispered—though in my head I finally said it. Bigfoot. This is a Bigfoot.

But you’re dying.

He let out this soft, choking sound. Not a growl—more like a man trying not to cry. The smell of wet fur and blood hit me. My hands moved on their own. Field assessment, pressure on the wound, checking for shock. I told myself I was crazy, that no sane doctor helps a Bigfoot in the woods. But when his fingers closed weakly around my wrist, massive and warm, I knew I wasn’t walking away.

I had a first aid kit in my pack. Bandages, antiseptic, trauma shears. I worked fast, the way you do in the ER when the clock is against you. Cleaned the wound, packed it, wrapped it tight. He watched me the whole time. Never tried to fight, just breathed shallow and fast, steam rising from his mouth in the cold air.

When I was done, I sat back on my heels. “I’ll get help,” I said. “I’ll figure this out.” But even as I said it, I knew I wouldn’t call anyone—because the second I did, he’d be gone. Caged, studied, destroyed.

The sun was already sinking, throwing cold blue light through the trees. I had him half-dragged, half-sledded on a cheap plastic tarp I’d found at my truck. Every pull felt like dragging a refrigerator full of wet sand. Gravel crunched under my boots. My shoulders burned. He was only semi-conscious, giving these low, broken sounds with each bump. Every time he exhaled, I smelled blood and damp fur and pine needles. I kept thinking, “This is insane. I am hauling a Bigfoot to my truck. I will lose my license, my freedom, everything.”

At the edge of the old logging road, I stopped. The sensible thing was call Fish and Wildlife or the sheriff or somebody. Let the professionals handle it. But I pictured cameras, helicopters, scientists in white coats. I pictured this creature strapped to a table under surgical lights.

Instead, I backed my truck closer, heart slamming, listening for any ATV, any human voice—only wind through clear cuts and a distant chainsaw miles off. I told myself I’d just get him somewhere safe for the night, stabilize him, then decide what to do.

Getting him into the truck bed took twenty minutes. I used the tarp as a sling, the tailgate as a ramp, and every bit of strength I had left. When I finally slammed the tailgate shut over that massive shape, the whole truck rocked on its suspension. I threw a canvas tarp over him, piled camping gear on top to hide the shape.

Driving out, every shadow looked like a deputy. Every parked car at a trailhead looked like a hunter who might glance in my truck bed. I couldn’t stop smelling blood on my hands. The whole way back to the highway, I kept checking the rear view mirror, expecting flashing lights, but the road stayed empty. The forest kept its secrets for now.

Rain hammered the tin roof in bursts, then eased to a soft patter. An old fluorescent light flickered over the stalls, humming like a tired refrigerator. Dust motes spun in the cold air.

I had access to the barn through an old farmer patient who let me use it for storage when I went camping. He didn’t ask questions. I backed the truck in, closed the doors, and just stood there with my breath fogging in the beam of my flashlight. The barn smelled like ancient hay, motor oil, and mouse droppings. Now it smelled like blood and wet fur.

I got him onto a pile of hay bales in the back stall. He was conscious enough to move a little, groaning when his leg dragged. I’d brought IV fluids from my own stock, antibiotics, pain meds. I dosed by weight, guessing, praying I wasn’t killing him.

“This is temporary,” I whispered, more to myself than to him. “I am not keeping a Bigfoot in a barn. I’m not that crazy.” His eyes tracked me, pupils wide in the dim light. He didn’t try to stand. He just breathed slow and shaky, steam rising from his fur into the cold.

I sat on an overturned bucket and watched his chest rise and fall, counted the breaths, listened to the rain. At some point, past midnight, I thought I heard three hollow knocks on the barn wall, slow, deliberate. I stood, flashlight shaking in my hand, walked to the door, listened. Nothing but rain and wind. Maybe it was loose boards. Maybe a branch, maybe my mind playing tricks. But when I turned back, his eyes were open, watching the wall where the sound had come from.

I turned off the light and sat with my back against the stall all night, listening to his breathing in the storm.

That was the first night I didn’t sleep. It wouldn’t be the last.

The barn always smelled like hay, iodine, and that wet fur musk that sank into my clothes. Outside you could hear the highway faintly and closer, the drip of rain from the eaves. Inside was its own world.

By January, his leg had knitted enough that he could put weight on it. I’d splinted and re-splinted, changed dressings by the light of that single hanging bulb that buzzed with flies even in winter. My stethoscope against his chest picked up a slow, steady rhythm deeper than any human’s. I stopped thinking of him as the creature or it and started calling him you in my head.

“You’re healing,” I’d say, checking the wound. “But I don’t know what normal is for a Bigfoot.”

He watched everything. When I brought apples, he’d sniff them first, then break them with careful, almost delicate hands. Once he pushed one back toward me, like sharing.

I knew how insane it was. Every shift at the hospital, I’d almost blurt it to a nurse, then swallow it down. They joked about Bigfoot callers on the radio. I laughed along while picturing him waiting in the dark, trusting me. His slow exhale at night became my metronome. When it paused, my chest tightened with fear.

I started bringing a sleeping bag, staying over on my nights off. Sarah thought I was camping. I let her think that. The lies came easier than I expected.

One February night, I woke to find him standing at the stall door, looking out the small window at the moon. He was still favoring the leg, but he was up, moving. He didn’t notice me watching. He just stood there, massive shoulders silhouetted against the window, one hand resting on the frame. For the first time, I wondered if keeping him here was cruel. But when I moved and he turned and his eyes met mine—calm, not afraid—I told myself it was worth it.

Monitors beeped, radios crackled. The ER smelled like antiseptic, burnt coffee, and human fear. My co-workers started to notice I’d vanish on my days off, leave early from staff parties, duck out of conversations mid-sentence when I realized I was late with feed or dressings.

“You still doing those camping trips, Doc?” a nurse asked one April night, rain streaking the ambulance bay windows. Yeah, need the woods, I said, thinking, I need to get to the barn. He’ll be waiting.

Now and then a trauma roll-in would be a hunter. Camo still wet, talking about something big they’d seen in the timber up near Keno. They’d say, “Damn thing in the woods.” But someone in the room always chuckled. “Hear that? More Bigfoot stories.” I kept my face blank. Inside, my stomach clenched. I’d replay their words later, alone in my truck, weighing whether any of them had shot him that October night, whether they were still looking.

Driving back roads at 2 a.m., wipers squeaking, I’d crack the truck window. The smell of wet fields and manure mixed with the memory of that barn musk. It grounded me, reminded me why I was lying to everyone I knew.

Sarah asked once why I smelled like hay. I told her the farmer let me store gear in his barn. She didn’t push. The lies piled up. Small ones, then bigger ones. I told myself I’d stop soon, move him somewhere wilder, release him when he was strong enough. But each time I opened the barn door and saw him rise slowly in the half dark, relief washed over me like a fever breaking. I wasn’t ready to let go.

By summer, I’d stopped pretending it was temporary. I bought a tarp to cover the truck bed permanently. I rerouted my drives to avoid the ranger station. I started researching isolated property for sale. I was planning a life around a Bigfoot in a barn. And I didn’t even feel crazy anymore.

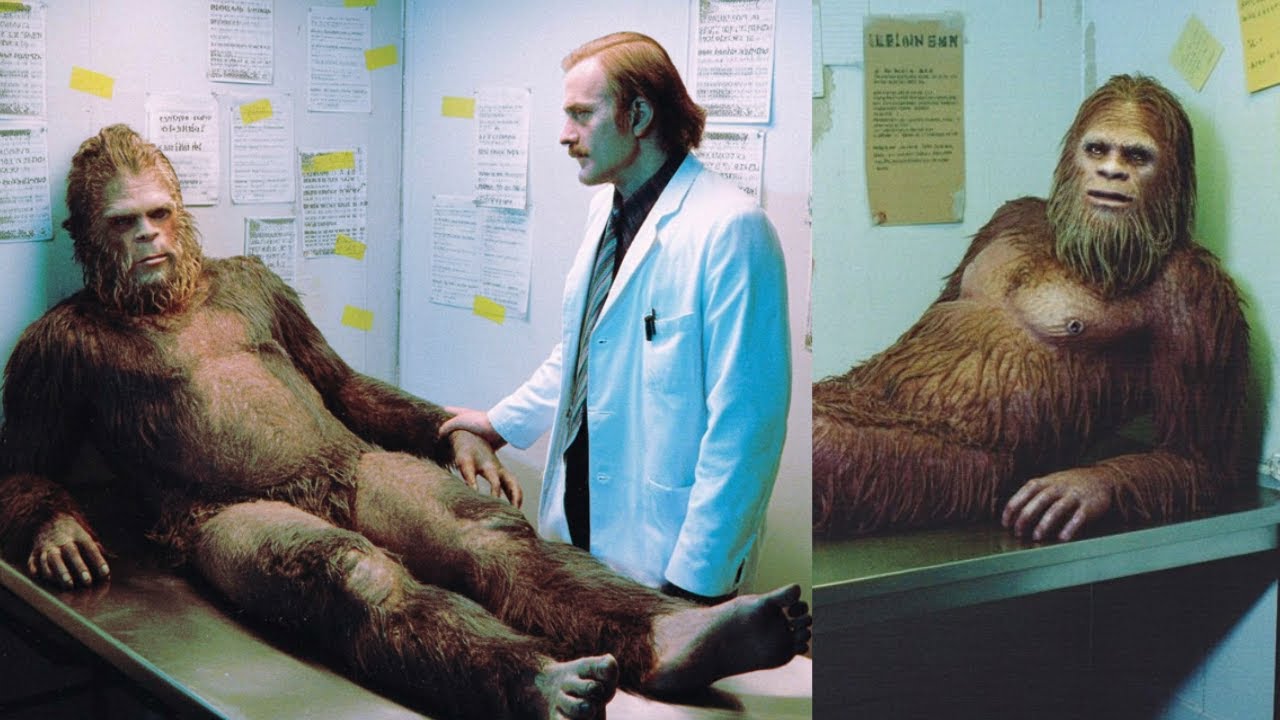

Crickets outside, distant dogs barking. Inside, just the buzz of the light and the rustle of hay. The air was warm and thick with that familiar smell. I don’t know why I did it that night. Maybe guilt. Maybe the doctor in me wanting documentation. Maybe I just needed proof for myself that this was real.

I propped my old phone on a feed bucket. Red recording dot blinking. “Okay,” I said softly. “I’m going to get close. All right. Just stay calm.” My voice shook. “Nobody’s going to see this but me.” He sat in the stall, shoulders hunched, watching the phone with open suspicion. When I stepped closer, stethoscope in hand, his chest rumbled—not threatening, more like nervous—his fingers flexed, then relaxed.

The video is grainy. You can hear the barn, the rain on the roof, my breathing. You can see my hand on his chest, hair parting under my fingers, the rise and fall. At one point, he looks directly into the camera. You can’t mistake that for a man in a suit.

I watched it once all the way through, alone in my kitchen at 3 a.m., refrigerator humming loud in the silence. Sarah was asleep upstairs. I sat at the table with my phone, volume low, watching proof of Bigfoot fill the small screen—his eyes, his hands, the way he breathed. Then I powered the phone down and hid it in a box of tax records in the garage. I knew if anyone saw that footage, he would never be safe. There’d be hunters, scientists, government people. They’d track him down, cage him, cut him open to see how he worked.

The phone stayed in that box for years. I told myself I’d delete it someday. But I never did. Because some nights, when the doubt crept in, when I wondered if I’d imagined the whole thing, I needed to know it was real. I needed proof that Bigfoot existed, even if I’d never show a soul.

By 2017, I’d moved him. The barn felt too exposed. Too many people asking why I drove out there so often. The farmer was getting old, asking questions I couldn’t answer. I bought a scrubby piece of land near Matlock with a sagging cabin and a thin line of firs. The cabin smelled of mold, mouse droppings, and the cheap pine cleaner I used to chase those smells off. I reinforced a back room, boarded windows from the inside. I hated doing it. It felt like building a cell, but I told myself it was safer for him than a lab, safer than a bullet.

He was moving better by then, strong, wary. At first, I only let him out at night, rope light off, me standing on the sagging porch with a flashlight I barely used. The forest was a wall of damp black.

After a while, I started finding things on the porch rail in the mornings. A bundle of ferns woven clumsily together. Three smooth riverstones stacked. A single crow feather, black and perfect—little offerings.

“I don’t know if this is normal Bigfoot behavior,” I muttered once, picking up the stones. My voice sounded small in the quiet. The air held that damp, loamy smell, and somewhere in the trees, something big moved. Branches ticked against each other. A soft huff, almost like a sigh.

I started leaving apples on the rail. I never saw him take them, but they were always gone by dawn, and the stones would change, rearranged or replaced with new ones. Part of me wondered if I was being studied right back.

Sarah and I had divorced by then. She’d met someone else, someone who didn’t disappear into the woods every weekend. I didn’t fight it. How could I explain? The cabin became my real home. The one in town was just a place I slept between shifts.

Out here, with the smell of wet earth and the distant sound of movement in the trees, I felt like I was protecting something sacred, even if I couldn’t name it out loud.

One morning in the spring of 2019, I found him standing at the treeline, completely still. I’d come out with coffee, the porch boards creaking under my boots. He was maybe fifty feet away, morning mist hanging between us. He wasn’t hiding. He was just there.

I froze. After nine years, this was the first time he’d let me see him in full daylight. He looked older. Patches of gray in the dark fur along his shoulders. The scar on his leg was a pale line through the hair. His eyes, though—still sharp, still watchful.

We stood like that for maybe two minutes, neither of us moving, just looking. Then he did something I’ll never forget. He raised one massive hand and placed it flat against a cedar trunk. Three times, slow and deliberate, he struck the wood.

Three knocks.

The sound echoed through the clearing, low and hollow. Then he turned and walked back into the forest, branches closing behind him like a curtain.

I stood on the porch, coffee going cold in my hand, heart hammering. That night, lying in the cabin with the window cracked, I heard the same three knocks from somewhere deep in the trees. A call, a signal. I didn’t know what it meant, but I knew it wasn’t a threat. It felt more like acknowledgment, maybe even gratitude.

I’d spent nearly a decade hiding him, feeding him, keeping him safe from a world that would destroy him for being different. And he knew it.

I never told anyone about that morning. Not Sarah. Not my daughter who called once a month. Not the bartender at the Matlock Tavern who thought I was just another lonely guy in the woods. But I started saying the word differently in my head. Not Bigfoot like a myth or a joke. Bigfoot like a name. Like someone I knew. Someone who trusted me when he had every reason not to.

I think that’s when I stopped feeling like I was keeping a secret. I was keeping a promise.

Wind pushed hard against the cabin that night, making the old boards creak. The single lamp in the kitchen threw a yellow puddle of light over the scarred table. Outside, I could hear the trees grinding against each other. That deep forest groan.

I’d been careless. Fifteen years of secrets makes you sloppy in strange ways. I’d stopped inventing alibis as carefully, trusted my routines too much. People just accepted that Dr. Carr liked his time alone.

My nephew Josh didn’t. He showed up unannounced that October night, headlights sweeping across the yard, his truck crunching the gravel. He’d been worried, he said, about all my disappearing, about your Bigfoot obsession. He joked, because the family knew I’d listen to those old radio shows. The word hit different coming from him. Sharp, mocking, but curious.

While I made coffee, the cabin filled with the smell of old grounds and damp wool from my jacket. The refrigerator hummed too loud. I heard a floorboard shift in the back room just once. Josh’s eyes flicked toward the hallway.

“You got somebody staying here?”

“No,” I said too fast. My heart crawled up into my throat. Just the house settling.

Then from the back of the cabin, three slow knocks on the inside wall.

He went pale. “What the hell was that, Uncle Dan?”

I had no more lies ready.

Now, as I talk, the rain has turned to a fine mist on the windows. A car passes outside, tires hissing on wet pavement. The baseboard heater clicks on and off, on and off.

Josh saw enough that night. The way the back door frame was splintered from the inside. The smell—wet fur and earth and something like smoke rolling down the hall when I opened the reinforced room just a crack to check on him. The shape in the darkness too tall for the door frame, retreating when the light hit.

Josh didn’t say Bigfoot again. He didn’t say anything at all for a long time. I got him to leave somehow, swore him to secrecy. I told him that if anybody ever came looking, they wouldn’t be coming to protect him. They’d be coming to cut him open, to prove he existed, to destroy the one thing nobody was supposed to believe in.

A week later, I went back to the cabin and found the room empty. The boards pulled loose from the inside, neatly stacked against the wall. On the porch rail sat three riverstones, balanced carefully, and one old apple, untouched, browning in the cold air. No broken doors, no blood, no struggle, just absence and that fading smell.

I don’t know where he went or if he’s alive. I don’t know if anybody else ever saw him walking out of those woods at dawn. All I know is some nights when the house gets too quiet, I still hear three hollow knocks in the back of my mind. I tell myself it’s nothing. Memory playing tricks. Old wood settling.

But I say Bigfoot now the way you say a person’s name when you miss them. The phone with the video is still in that box in my garage. I haven’t looked at it in years. Maybe someday I’ll delete it. Maybe I won’t. For now, it’s enough to know I kept one promise in a lifetime of broken ones. I kept him safe. And when the world finally got too close, he knew how to disappear.

That’s all I wanted to say. The tape is almost done. The rain has stopped outside. The highway hums in the distance. And if you listen close enough, underneath all that noise, you might hear what I hear.

Three soft knocks.

Always three.

Somewhere out there in a forest I’ll never name, something remembers.