Caitlin Clark: An Accelerant To An Already-Burning Flame

Caitlin Clark has become part of a conversation centering women’s basketball in issues that have long needed the spotlight, including queerness, whiteness and how we pick our saviors.

I’ve resisted writing about the WNBA for a while, in part because it’s a very recent interest of mine and I’m wholly underqualified to discuss it from a technical or historical perspective and this is, in part, a football newsletter.

It also happens to be a dead moment in football news and the WNBA is dominating the discourse. That conversation has made contact with much broader political and cultural elements that are worth discussing.

Bumbling into a discussion about a sport I know little about and topics I have had to learn from the outside looking in is part of the problem within this conversation, so it is important to me to recognize the pieces and writers that inspired this work.

Frankie De La Cretaz has been covering sports from the perspective of gender and queerness for years. The Out of Your League Substack and their piece on the trope of the queer villain inspired this piece. De La Cretaz co-wrote Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League with Lyndsey D’Arcangelo, another writer whose WNBA coverage has informed my perspective. In particular, D’Arcangelo’s piece on the hot-take culture surrounding Caitlin Clark has helped me shape my thoughts on how to approach public discourse on the topic.

Jackie Powell’s 2022 piece on Brittney Griner’s imprisonment in Russia was remarkably helpful, as was Larisha Paul’s recent deeply impactful piece on the torturous nature of the imprisonment.

Michael Eric Dyson, a former Penn professor, wrote an excellent piece about the intersection of race, the WNBA and Caitlin Clark that I drew inspiration from. Jim Trotter, a sportswriter I’ve long admired, contributed to that same discussion, looking outward to fans rather than internal to the WNBA megastructure.

Lindsay Gibbs’ Substack about women’s sports, Power Plays, has also been informative. I most recently read her piece on embracing selfishness in women’s sports.

In fact, the end of Gibbs’ April 30th piece on the change coming to the WNBA – prophetic in many ways – is a great place to begin this one.

Caitlin Clark, the Savior

Clark has been anointed as the most recent savior of women’s basketball. The Iowa sharpshooter has been tasked with – or even prophesied to – pull the sport out of its dredges and into mainstream consciousness (and profitability).

This narrative has twisted its way into dark corners, even suggesting that players and coaches show deference to Clark for her impact – as if Clark could consistently draw crowds playing in an empty arena against nobody, or that there would be worth to an achievement against a league with no talent.

This mirrors individualistic discourse in every arena of accomplishment. There are no self-made “great men” of history. These are more than your Alexander the Greats and your Adolf Hitlers. They can be your Thomas Edisons and Elon Musks or even your local car salesman.

President Barack Obama’s “You Didn’t Build That” was not some poor attempt at gaslighting but rather an explanation that we don’t have scientists and businessmen without an infrastructure built by others – schools, roads, a medical system, an agricultural system that delivers food across the country, and the foundation of knowledge that these scientists build off of – Edison can’t innovate on the lightbulb without the centuries of physics and chemistry knowledge before him.

Vice President Kamala Harris tried to explain the same thing in perhaps the most baffling manner possible and it didn’t land. That may have had more to do with her anecdote than the difficulty of the concept but it remains the case that the idea that “no one is an island” is difficult to convey.

Caitlin Clark is a sea change in the coverage of women’s basketball, but she is not a singular phenomenon. Her popularity cannot exist without the infrastructure – both physical and cultural – for women’s basketball to exist.

Women’s basketball, like any social organization, is a community.

That seems like an obvious point to make, but it evidently needs to be made.

It’s not just that Clark is benefiting from and building on the legacies established by Tina Thompson, Cynthia Cooper-Dyke, Sheryl Swoopes, Lisa Leslie, Lauren Jackson, Sue Bird as well as modern legends like Candace Parker, Elena Delle Donne, Diana Taurasi and Sylvia Fowles.

It’s that she’s also building on the sacrifices made over a century ago by Senda Berenson Abbott, teaching basketball to women at Smith’s College just a year after James Naismith invented it. It draws on a game called netball, adapted from basketball to create a more socially acceptable version for women to play. The Women’s Basketball League, founded in 1978, was a critical part of the development of the later, more successful, WNBA.

Current superstars Breanna Stewart and A’ja Wilson – who could be in the middle of taking a run at the GOAT title herself in short order – were a part of this building process, too. Rising stars like Napheesa Collier and Sabrina Ionescu are part of it.

That includes former Fever star Tamika Catchings, too. Not only that, Clark is playing with several former talented lottery picks – Kelsey Mitchell, NaLyssa Smith and Aliyah Boston, the latter of whom won rookie of the year last year.

None of this is to suggest that Clark is unaware or ungrateful – this piece isn’t really about her, but about the reaction to her.

Clark is aware of most or all of this history. The broader discourse is not. The broader discourse is poisoned by, among other things, something that has plagued historians for decades – the incessant (some would argue neoliberal) need to identify an individual as a proximate cause for broader events instead of the systems that birthed them.

Even recently, it’s difficult to imagine the state of women’s basketball without Sedona Prince’s viral video demonstrating the awful disparity in how women and men were treated during the NCAA tournaments.

It is unquestionable that Prince’s video was foundational to the change in how the NCAA treated women’s basketball. The Kaplan Report, a 114-page report on this disparity commissioned by the NCAA after Prince’s video went viral, begins by acknowledging Prince’s video and calls it the “shot heard round the world” on this issue.

That motivated a change in how the sport was funded by programs and treated in broadcast negotiations and set the stage for a star to emerge.

Building a Phenom

Clark is not the first star to capture ESPN’s attention and this fact alone should tell us that investment and marketing play as large a role as talent and playing style to popularity – Rebecca Lobo’s 1995 run was truly stunning, capturing an audience in total viewership not matched until 2023, when Iowa and LSU faced off in the championship game.

But Lobo’s run at the title was not the most-watched women’s basketball tournament – it’s just the most recent one that tends to get included in aggregated data covering the event. As far back as 1989, Tennessee’s win over Auburn drew 7.22 million viewers, just short of the 1995 total that Lobo’s Huskies drew at 7.44 million. Tennessee’s run in 1991 drew 7.33 million.

Jim Gund/NCAA Photos via Getty Images

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, these were normal totals for the culmination of the women’s basketball season.

And none of those three Finals are in the top ten for viewership, even though UConn’s 1995 run was the highest total for almost 30 years. In 1993, Sheryl Swoopes’ Texas Tech Raiders drew an audience of 7.81 million for the final, while a year prior a Stanford Final Four game against Virginia drew 8.08 million.

Various games throughout the 1980s and 1990s pepper the top ten list, but it might surprise people to learn that it was 1983 that drew the largest pre-Clark audience in college women’s basketball history at 11.84 million. Cheryl Miller’s 1983 USC squad took on Kim Mulkey’s Louisiana Tech to a viewership of roughly five percent of the American population.

For context, Clark’s 2023 championship game – viewed by 9.92 million people – was broadcast to a number equivalent to three percent of the American population.

The difference between the 1995 viewership of 7.44 million and the 1996 viewership of 3.5 million is not solely due to the fact that Lobo graduated and that neither Tennessee or Georgia had “marketable” stars in the 1996 championship game (Tennessee had Chamique Holdsclaw, after all).

It’s that the 1995 game was aired on network television – CBS – while the 1996 game was aired on cable television – ESPN.

ESPN would continue to hold the tournament to a viewership of about 3.5 million – with a bump up to 5 million during Taurasi’s UConn run – until 2022, when they achieved 4.8 million viewers, their highest since Taurasi.

The difference between network television and cable television for viewership – and as a testbed for future marketing opportunities – has had an enormous impact on the popularity of the sport and its perceived ceiling as a product.

This distinction between network and cable availability has not gone unnoticed by those familiar with women’s college basketball. High viewership numbers were the norm, not the exception. And as attendance for women’s basketball games soared, viewership numbers couldn’t follow — because the broadcast structure simply did not allow it.

In 2023, Clark made the final game, where viewership doubled to 9.9 million. But that’s not the only variable that changed – the game was also aired, for the first time, on ABC. Just like it was again in 2024.

ABC’s decision to air the final in 2023 wasn’t made with Clark in mind – they had announced the decision in August of 2022, a likely downstream effect of Prince’s video and the Kaplan report. Indeed, “Paige Bueckers” was a more popular search term in 2022 than “Caitlin Clark” and there was no reason to assume that Iowa was a lock to make the final.

Her single-game scoring record accomplishment against Michigan in 2022 was covered like any other Sportscenter news item, washed away in the analysis of the upcoming Rams-Bengals Super Bowl a week later.

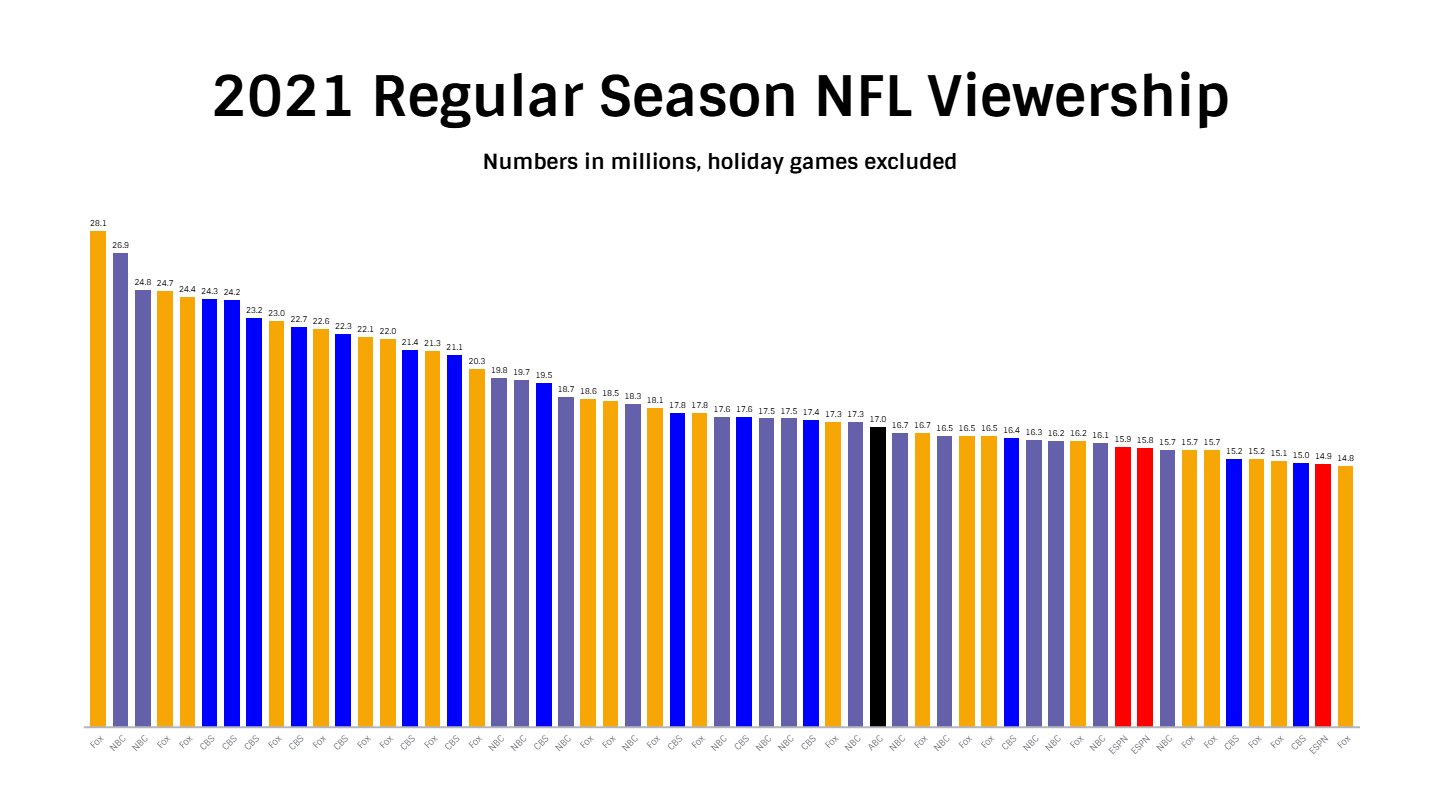

This move to ABC was a big change. Before ESPN regularly simulcast Monday Night Football to ABC in 2022, the most-watched regular-season NFL broadcasts were all network television.

In 2021, the (non-holiday) regular season games with the most viewership by each broadcast partner were:

28.1 million (Fox’s broadcast of the Week 11 matchup between the Cowboys and Chiefs)

26.9 million (NBC’s broadcast of the Week 4 matchup between the Buccaneers and the Patriots)

24.3 million (CBS’s broadcast of the Week 2 game between the Cowboys and the Chargers)

15.9 million (ESPN’s broadcast of the Week 14 game between the Rams and the Cardinals)

Yellow is Fox, Purple is NBC, Blue is CBS, Black is ABC and Red is ESPN

It’s very clear that the decision to silo the women’s national championship game had a much bigger impact over the course of its life than individual star power.

The stars were always there, from Stewart to Wilson to Brittney Griner to Skylar Diggins-Smith to Parker. They played exciting basketball and were “marketable” players by nearly every metric. That also includes non-Finals participants like Ionescu.

None of that is to say that Clark doesn’t have tremendous gravity. It is undeniable that her presence played an enormous role in the historic numbers we saw in the NCAA tournament.

The women’s final game outrated the men’s final game this year, in big part due to Clark’s presence. But that cannot happen without infrastructural decisions that removed the artificial limit on the reach of the women’s game.

Clark is deserving of the star title. She was undeniably an elite talent in the tournament. She plays a flashy and effective game, with deep three-point shots reminiscent of Steph Curry’s incredible emergence on the scene. Press about Clark ramped up well before the tournament and her ascendance up the scoring charts was well-tracked by sports highlight shows.

And though we cannot isolate all of the things that makes someone a star, it’s difficult to chalk up Clark’s rise to fame purely to her playing style or some other unique feature without asking why Kelsey Plum, who Clark passed on the scoring leaderboard, didn’t receive the same attention. It’s not as if Ionescu wasn’t also hitting logo 3s in college.

Ionescu was doing this stuff to win buzzer-beaters against ranked opponents as a freshman.

One very relevant reason for why that attention no longer felt sparse has to do with the structure to support women’s basketball in 2023 and 2024 and the cultural cachet that had been built by players like Ionescu to open up the conversation of women basketball stars.

The Great White Hope

The interesting thing is, within the context of the mainstream presence of women’s basketball, both Plum and Ionescu did both receive extraordinary attention. Both had been tasked with saving women’s basketball and both were also exciting deep-shooting guards. Plum didn’t shoot as deep as Clark or Ionescu, but she hit a lot of threes and had sick handles – just as exciting.

The same burden was placed on Taurasi, Bird and Griner. Aside from Griner, all of these players had one thing in common: they’re all white.

The Griner exception isn’t meaningless, of course, but it’s worth examining why Clark received this treatment but Boston and Wilson didn’t. Maya Moore and Candace Parker were transcendent players but were not tasked with saving the sport like Taurasi was. Rebecca Lobo received more press than Holdsclaw or Arike Ogunbowale in the leadup to her rookie season.

There has been a lengthy history of the Great White Hope and Clark – willingly or unwillingly – has become entangled in that web.

It is important to point out that arguing the role whiteness plays in star-making is not the same as saying someone is a star because they’re white. In the same way nearly every successful actor is both talented and lucky, one does not diminish talent because one points out that luck played a role in success.

Clark has star power. She would have star power in a world without structural racism, heteronormativity or patriarchy – arguably even more. Rather, it’s to point out that a number of advantages have propelled Clark to a unique state against her peers.

The conversation surrounding this is very similar to the conversation surrounding Black quarterbacks in the NFL. Those resistant to the idea of extant racism in sports point to the success or regard held for Black quarterbacks – Lamar Jackson won an MVP, Cam Newton was picked first overall, etc.

This ignores the nature of modern racism. Blackness does not operate as a disqualifying checkmark to anyone but the most committed, explicit and virulent racist. Instead, racism on an individual level expresses itself in myriad ways.

These could come in the form of judging by a different set of standards. For example, Clark is an aggressive trash-talker. She had developed a reputation on both her high school and college teams of berating her own teammates. She loves trash talk. But it’s fellow rookie Angel Reese who’s earned a (negative) reputation for it.

Photo by Steph Chambers/Getty Images

Clark’s wholesome image – another dogwhistle – is a reason why I’ve been told by online commentators that Clark doesn’t talk trash. There are highlight reels of her trash talk! As a football commentator, I can’t help but compare this to the way Adam Thielen was perceived for the bulk of his career as a Minnesota Viking.

Thielen was a vicious trash talker, an image that was not transmitted to fans until around 2018, when a clip of Thielen yelling at Bill Belichick went viral. Thielen was always like this, even in training camp as a rookie in 2013. But the perception was that he put his head down and worked hard without complaint.

Nevermind that he complained so much in a game once that Kirk Cousins publicly apologized to him.

These are very much not criticisms of Clark or Thielen, at least from me. I love trash talk. Sports robbed of the emotions of the athletes are almost not sports at all. But it is notable that Reese and Stefon Diggs were labeled divas for their trash talk while Clark and Thielen weren’t.

It is also, separately, an incredible interpretation of Reese in particular – the image of Reese as an angry trash-talking villain is at odds with her style of play and pure expression of joy on the court. Reese is perhaps one of most expressive players in the league right now and she wears her happiness on her sleeve.

Of course, different interpretations of the same behavior are only one way that more subtle forms of racism get expressed.