A Veteran Met Bigfoot in 1975. Its Warning About Humans Will Shock You – Sasquatch Story

THE AMBER-EYED SENTINEL

A mysterious account told by Elias “Red” Vance

Chapter 1 — The Cabin at the Edge of Quiet

Most people think the things in the deep woods are monsters—mindless beasts roaming the dark with nothing in their heads but hunger. That’s what the movies teach you. That’s what officials would rather you repeat. But I learned the truth doesn’t always come with claws and snarls. Sometimes it comes in silence, in a feeling that the forest is holding its breath, and in eyes that look back at you with an intelligence you can’t explain away.

.

.

.

My name is Elias Vance. In the First Marine Division, the boys called me Red. I did two tours in Vietnam as a sniper. You learn a strange kind of patience in that job. You learn to be still until stillness becomes part of your bones, and you learn to end lives from distances that keep the act clean in your mind. I was good at it—too good—and when I rotated back stateside in 1975, I didn’t come home whole. The city felt loud and fake. Every car backfire yanked me back into the bush, reaching for a weapon that wasn’t there. Doctors gave it polite names—combat fatigue, shell shock. I called it what it was: hell.

So I ran. I bought a derelict cabin deep in the Cascades, miles from the nearest paved road. No electricity. No running water. Just cedar walls, a wood stove, my bolt-action Winchester, and enough quiet to drown in. I told myself I went up there to heal. The truth is, I went to hide—like a wounded animal crawling away so no one has to watch it bleed out.

For the first few weeks, the forest was just the forest. Wind in Douglas firs, squirrels chattering, deer passing through like ghosts. Then the pattern changed. It didn’t change loudly. It changed wrong. I’d wake up and find my woodpile rearranged—not scattered like a raccoon had been digging, but restacked into a neat pyramid I hadn’t built. I’d step outside and feel the hairs on the back of my neck lift as if a current had run through the air. Sometimes the birds stopped singing all at once, not gradually, but like someone had flipped a switch. That kind of quiet isn’t peaceful. It’s predatory.

I thought it was a cougar. Maybe a bear. I was a hunter. I knew animals. But then I found footprints that looked human and yet pressed three inches deep into hardpacked mud. I heard heavy timber snapping at three in the morning with a crack like gunfire. And there was a smell—wet pine and ozone, and beneath it something ancient, like the earth itself had been turned inside out.

The breaking point came at dusk. I was on the porch cleaning my Winchester when a rock the size of a grapefruit sailed out of the treeline and landed—softly, precisely—in the center of my clearing. It didn’t hit the cabin. It didn’t hit me. It landed like a placed token. A notification. A message that said: I can reach you, and I’m choosing not to.

That night, I didn’t sleep.

Chapter 2 — The Hunter and the Crosshair

Two days later I did what soldiers do when uncertainty starts to gnaw through the ribs. I decided to take control. I wasn’t going to sit in the cabin like prey returning to its burrow. I put on a homemade ghillie suit—burlap and local vegetation stitched into a miserable second skin—and climbed a ridge overlooking my clearing. I found a shallow defilade hidden by ferns and mossy rock, settled in, and waited.

Hours bled into hours. Cold crept into my marrow, that damp Northwest chill that doesn’t bite so much as invade. Around 0300, the moon broke through cloud cover and poured a pale silver wash over the clearing. That’s when I saw it.

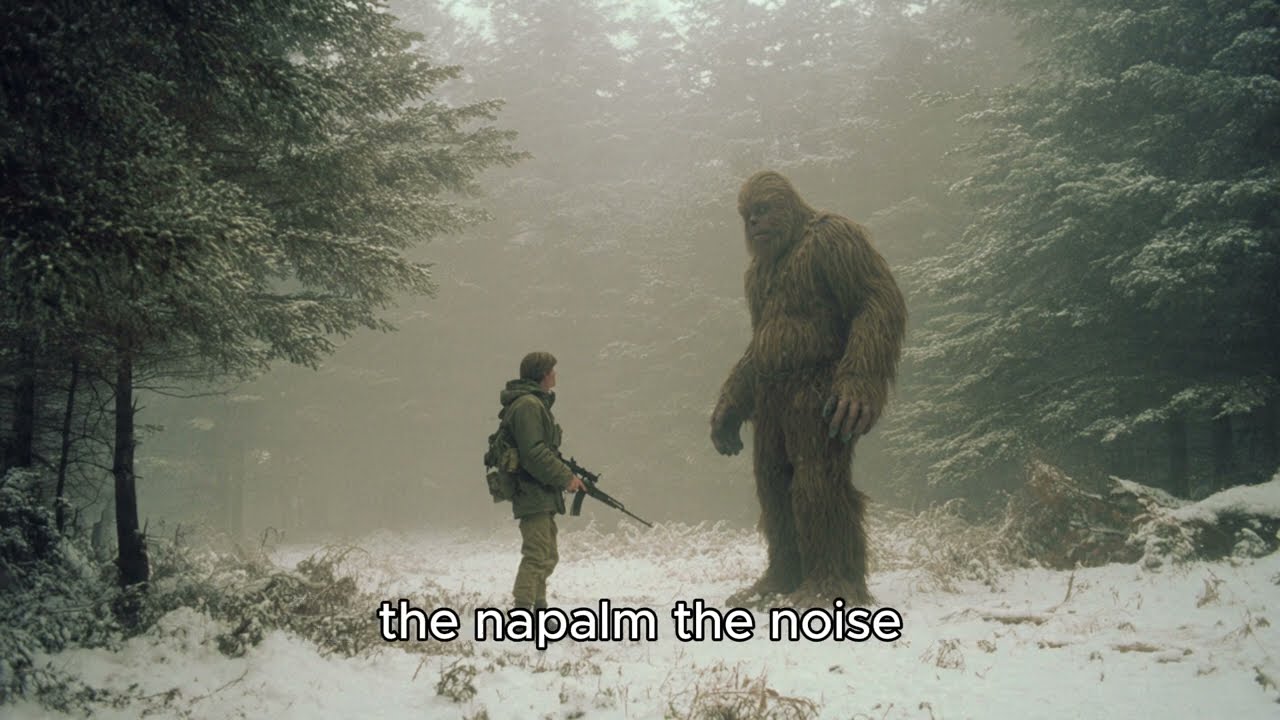

It didn’t step out of the forest. It separated from it—as if the shadow between two cedars decided to stand up and become a body. Colossal. Even from two hundred yards, I could tell it was eight feet tall at least, walking on two legs with a fluid rolling gait no man could mimic. For something so massive, it moved with a silence that felt like an insult to physics.

I raised the scope. The glass was clear. The crosshair settled on its chest. Center mass. A kill shot. I adjusted for windage the way muscle memory makes you do. Inhale. Exhale. Pause. My finger took up slack. Three pounds of pressure stood between the world I understood and a hole through something that should not exist.

Through the magnified lens I saw details that made the stories in tabloids feel childish. The fur wasn’t just hair; it was layered and dark like wet bark. Muscles rippled beneath it like steel cables. It stopped in the middle of my clearing, looking at the cabin as if weighing an idea. Then it turned its head.

Not toward the sky. Not toward the trees. Toward me.

It looked directly at the ridge, directly into my hide, directly at a man who was motionless, downwind, dressed to disappear. There was no way it could see me. And yet it did. I expected a monster’s face—snarling, stupid, hungry. Instead I saw a dark, deeply lined visage that looked old in a way no animal ever looks. And the eyes… amber, wide-set, intelligent. There was no aggression in them. There was curiosity. Weariness. A sadness so clean it made my throat tighten.

We locked eyes through my optic. My training screamed engage. Neutralize. Protect your perimeter. But my gut—my gut screamed do not fire. What stopped me wasn’t fear. I knew fear. This was recognition, sudden and uninvited. I was looking at something that carried a soul.

I eased my finger off the trigger and clicked the safety. In the silence, the sound was loud as a hammer strike. The creature dipped its chin—just slightly, but unmistakably. A nod. An acknowledgement. Then it turned and dissolved back into the treeline, vanishing so completely it felt like the woods had swallowed a secret.

I lay in the dirt until sunrise, shaking, and I knew my life had changed.

Chapter 3 — The Oldest Language

In the morning, my mind went to protocol. Report contact. Call it in. Request support. If I went down to the ranger station and said I’d seen a hostile bipedal entity eight feet tall, the response would be swift and violent. National Guard. Federal suits. Helicopters and fire and men who would turn mystery into evidence and label it “security.”

That was exactly why I kept quiet.

Looking into those amber eyes the night before, I understood something without words: it was hiding from us the way I was hiding from my own kind. We were both refugees, just from different wars.

So I chose a different kind of communication. Food. The oldest language in the world. I had surplus C-rations and a few MREs I’d “borrowed” before discharge. One evening I took an unopened pouch and set it on a stump fifty yards from the cabin, right at the edge of my safe zone. If it was just an animal, it would rip through the plastic and foil. If it was something else, it would figure it out.

By morning, the pouch was gone. Not torn to shreds—peeled open cleanly. The contents licked spotless. The foil pouch folded into a neat triangle and placed back in the center of the stump like a receipt. Next to it sat a closed ponderosa pine cone. Tucked into its scales were three blue jay feathers arranged in a perfect fan.

My hands shook when I picked it up. This wasn’t foraging. This was art. This was trade.

For months, it became our ritual. I left apples, jerky, sometimes a can of peaches. I opened the cans for him, stupidly worried about sharp metal, as if the creature wasn’t strong enough to tear a truck door off its hinges. In return, he left things. Sometimes useful—bundles of dry kindling tied with woven grass before storms. Sometimes strange—stones arranged in spirals. Sometimes medicinal—Devil’s Club root left on the stump after I twisted my ankle. How did he know I was limping? Because he was watching, always watching. Yet the sensation changed. It stopped feeling like menace and started feeling like protection.

I began talking to him at dusk. I know how it sounds—crazy old Red talking to the trees—but when you’ve spent years whispering into radios and waiting for answers that come late or never, you learn the world doesn’t require an audience to hear you. I’d sit on the porch, cigarette burning, and talk into the darkness. “Looks like rain tonight,” I’d say. “My knee’s acting up again.” There was never an answer in words. But sometimes a low vibration would rise in my chest, a hum so deep you felt it more than heard it—like a diesel engine idling underground. It said: I’m here. I’m listening.

And he understood violence. One afternoon a coyote got bold around my trash, snarling, showing teeth. Before I could even lift a boot, a rock the size of a baseball whistled past my ear so fast it blurred and struck the coyote in the ribs. Not a kill. A warning. The animal yelped and fled.

I stared up at the ridge. Nothing moved. But the message was clear: I can hit what I want. I choose restraint.

That was the moment I stopped thinking of him as a wild man. I began thinking of him as a soldier.

Chapter 4 — The Blizzard and the Drawing

Winter came like a conqueror. By November, the world turned into a grayscale photograph—green buried under four feet of white. Temperatures dropped so low the trees cracked at night like pistol shots, sap freezing and expanding until the wood gave up with a sharp report. Survival became work without end: chopping, melting snow, feeding the stove. If the fire died, I died. Simple as that.

One night in mid-December, the storm turned into a whiteout. Wind screamed down the valley at sixty miles an hour. My cabin groaned under the assault. I was hunched by the stove with whiskey just to stop the shivering when I felt it—no sound, just a heavy, soft thud against the north wall behind the chimney, as if something enormous had leaned in.

I grabbed the Winchester. Then I realized what it meant. The chimney stack was the warmest part of the cabin; the bricks radiated heat outside. He was out there, pressed against my wall, stealing warmth like a starving man.

My hand hovered on the doorknob. Brain said wild animal, unpredictable. Heart remembered folded foil, feathers, kindling, warning shots meant for coyotes—not me. I let go of the knob. I threw three heavy logs into the stove and opened the damper until the fire roared. I wasn’t heating the room anymore. I was heating the wall.

I leaned back in my chair with my head against that same north wall. Between my skull and his massive spine there were inches of timber and plaster. Back-to-back. Two soldiers in a foxhole, waiting out the bombardment.

That night I didn’t make small talk. I confessed. I whispered into the wall about Quang Tri, about a boy no older than twelve running messages, about orders and a shot and a face that never leaves you. The wind howled, but I knew he could hear me. His hearing was supernatural. When my voice broke, the hum answered—steady, grounding. When I began to shake, a slow rhythmic thumping came through the wall. Thump. Thump. Thump. Gentle as a heartbeat.

A creature the world insisted didn’t exist was calming me down.

Two days later the storm broke. Sunlight hit the snow so hard it hurt. I opened the door half expecting him to still be there. He was gone. But he had left a message.

The snow in front of my porch had been cleared—not shoveled, but swept smooth into a white canvas. In the center was a drawing made of punctures and lines. A large circle, perfectly round. Inside it, hundreds of tiny holes like a constellation of trees, people, life. Cutting through the circle was a jagged line, angry and sharp, like a wound. And at the edge lay a charred piece of wood from my own fire pit.

I stared until my breath felt thin. The circle was balance. The jagged line was destruction. The charred wood was fire—technology—me.

When I looked up, he was there at the treeline in full daylight, leaning against a fir like a sentinel. He pointed at the drawing, then at me, then at the sky. Then he did something that made my skin crawl even now. He opened his mouth and mimicked the sound of helicopter rotors—the thup-thup-thup of a Huey.

A Vietnam sound. A war sound. A sound that shouldn’t belong in a mountain valley unless it had been heard before.

He knew what I was. He knew what my kind brings into the garden.

Chapter 5 — Diesel Fumes and the Decision to Be the Villain

Spring didn’t bring peace. It brought machines.

One morning a low mechanical whine rose from the valley—bulldozers, chainsaws, skitters. To you, that’s construction. To the creature living in those woods, it was invasion. I packed my rifle and moved down the mountain to scout. Three miles from my cabin, I found them: a survey crew and loggers carving a road through the trees. Ancient cedars that had stood since the Civil War fell in minutes. The ground churned into mud and oil. Exhaust and sawdust thickened the air until it tasted like pennies.

But the machinery wasn’t what terrified me.

Thirty yards behind the men, under the deep shadow of the canopy, he stood perfectly still. Only the amber eyes gave him away, burning like coals. His lips were pulled back, teeth showing—white, chisel-like. Rage vibrated in him, contained by sheer will. His hands snapped a thick branch as if it were dry twig. He wasn’t watching the men. He was stalking them.

He was going to kill them all.

And if he did—if six men were torn apart on that mountain—the response wouldn’t be a sheriff. It would be a purge. The woods would burn. Helicopters would fill the valley. Men in uniforms would erase everything until the world could pretend it never happened.

I had a choice: let nature take its course and watch a massacre, or intervene and become the villain to save the hero.

I stood up and walked down the slope like a madman with a rifle. I hadn’t shaved in months. My clothes were stained with mud and grease. I looked like every nightmare people tell themselves about mountain hermits. I confronted the foreman, let my voice turn hard, and when he laughed about permits, I racked the bolt on my Winchester.

The laughter died.

“I don’t care about your paper,” I told him. “You’re waking up things that need to sleep. Turn those machines around now.”

It was mostly bluff. I wasn’t going to shoot a man. But they didn’t know that. They saw a veteran with a thousand-yard stare and a high-caliber rifle and decided the forest wasn’t worth it. In twenty minutes they packed up, cursing, and drove away. Silence seeped back into the trees like water returning to a riverbed.

Then he stepped out.

He walked into the churned mud, looked at the felled trees, and knelt by a severed stump. He ran his massive hand over the raw wood in a gesture that looked like mourning. When he stood and faced me, I expected gratitude.

There was none.

There was urgency. He closed the distance until he towered over me, smelling of musk, pine resin, and something like ozone after lightning. He pointed at my chest, then down the valley toward town, then swept his arm as if pushing me away.

Go.

Not banishment. Warning. They would return with more.

Chapter 6 — The Hand, the Vision, the Countdown

Three nights passed. No sheriff. No flashing lights. Just wind rattling shingles and the sense that something was being arranged in the dark. Then, at 2000 hours, the cabin’s air pressure dropped like an elevator falling. My ears popped. The fire sputtered and turned a strange low blue. Static prickled along my arms until the hair stood straight up.

The door creaked open.

He ducked to enter, folding that enormous frame into my small cabin. Up close, he filled the room with sheer presence. His fur was matted with pine needles and sap. Scars roped across his chest—old wounds healed thick and hard, like a history written in flesh. He looked at the rifle in my lap, then at my eyes. He didn’t speak. He didn’t need to.

He reached out slowly, giving me every chance to do what men do when they’re afraid.

I let the rifle slide to the floor.

He stepped forward and placed his massive, leathery hand on top of my head. The moment skin touched skin, the world tilted. It wasn’t a voice. It was a flood—emotion and memory that wasn’t mine, poured into me like a dam breaking. I wasn’t in the cabin anymore. I was high above the continent, watching forests spread vast and green. Then I saw the infection: cities blooming like black mold, highways veining through the green like strangling cords. I felt grief so deep it was almost geological.

Then came the warning.

He showed me humanity as fever—a temporary sickness the earth was trying to sweat out. He showed me his kind not as animals, not as legends, but as antibodies: an immune system waiting in the shadows while the fever burns hot. And then the vision shifted forward, flashing images that made Vietnam look small. Skies the color of bruised iron. Water rising. Fire returning to the source. And most terrifying of all, I saw them—thousands emerging from caves, from deep ice, from places we pretend don’t exist. Not to save us. To clean up after we were gone.

The message rang in my bones: the fever is breaking. Prepare.

He pulled his hand away. I collapsed out of my chair, gasping like a drowning man. My nose bled. My head felt split open. He looked down at me with those sad amber eyes and pointed at the calendar on my wall—1976. He shook his head. Then he held up five fingers, closed them into a fist, and opened them again.

A countdown.

He turned and walked out into the night, leaving my door wide open. Cold air flooded the cabin, but I was sweating. I sat on the floor for hours, shaking, understanding too late that the monster wasn’t the creature in the woods. The monster was the civilization I had fled, and it had started to follow.

At sunrise, the sound came—rotors chopping the mountain air. Black helicopters flying low, unmarked. Men dropped on ropes wearing black fatigues without patches, moving in fire teams, clearing my cabin like it was an enemy compound. Flashbang pops. White smoke. Radios crackling.

They weren’t there for me. I was just a loose end.

They were there for him.

I ran into the trees and climbed for higher ground, moving on instinct and old training. Then I heard it—a roar that shook snow off branches, something primal and infrasonic that hit the gut like a punch. I saw him cornered against rock, bullets striking his fur in puffs of dust, blood dark on his chest. He fought like a force of nature, throwing grown men like rag dolls, but there were too many of them. And then I saw a third helicopter hover low, a heavy weapon swinging into position like the final sentence of a trial.

I didn’t think. I didn’t weigh the consequences of firing on my own. In that moment, they weren’t countrymen. They were the virus.

I went prone, set the bipod, and aimed at the tail rotor. Range three hundred yards. Wind full value left to right. A one-in-a-million shot, the kind you only take when you have nothing left but conviction. I exhaled and fired. The Winchester cracked. Sparks showered from the tailboom. The tail rotor disintegrated, and the aircraft spun into a screaming spiral before crashing hard into the snow.

Chaos. The firing stopped. In that sliver of distraction, the creature looked up and found me on the ridge. Even from that distance I saw exhaustion in his posture and blood on his chest. I stood and waved north—toward lava tubes I’d known about, deep caves under the mountain where the world thins out. He didn’t hesitate. He turned and sprinted away on all fours with a speed that made every campfire story feel timid, and he vanished into the timber before they could regroup.

I disappeared too.

A week later, when I returned, my cabin was gone—not burned, but erased. Foundation stones cracked from intense heat. The ground scorched black in a clean radius. My truck missing. Even the stump where we traded gifts had been dug up. A textbook sanitize operation, scorched earth, as if the mountain itself had been ordered to forget I ever lived there.

I drifted after that, changed names, worked cash jobs, stayed off the grid. For decades I waited for a black sedan to find me. It never did. Maybe they thought the fire killed me. Maybe they decided the woods would finish the job. I never saw him again—not with my eyes.

But years later, when Mount St. Helens tore itself open and turned day into night, I felt that same vibration in my chest, like the earth clearing its throat. Like an immune system waking up.

Now I’m an old man. Fifty years have passed, and the world looks more like the vision he poured into me than I ever wanted to believe. Fires hotter. Storms bigger. Water rising. People angrier, louder, hungrier. The fever peaking.

If you ever walk into the woods and feel the silence press against your ears, if the birds stop singing like they’ve been ordered to stand down, don’t run. Don’t shoot. Bow your head. Show them you’re not part of the disease.

Because when they come back, they won’t be throwing rocks.