Inside Vietnam’s Darkest Secret: When Soldiers Rebelled Against Command

On a bleak, rain-soaked morning at Firebase Mackey in March 1971, Captain Brian Donovan knelt in the red clay of the central highlands. In his hand, he held a small, twisted piece of metal: a pin from an M26 fragmentation grenade. It was stained with the blood of his first sergeant, Miller. But the horror of the moment wasn’t just the death of a comrade; it was the realization that the grenade hadn’t been thrown by the enemy. It had been rolled into Miller’s command bunker by an American soldier—someone who had eaten breakfast with them just hours before.

This was “fragging,” the chilling name given to the murder or attempted murder of military leaders by their own subordinates. Between 1969 and 1972, there were over 900 documented incidents, but historians believe the actual number, including disguised combat deaths and unreported attempts, was significantly higher. It was the most visible symptom of a total systemic collapse that nearly broke the United States military beyond repair.

The Illusion of 1965: A Professional Machine

To understand the depth of the fall, one must look at the height from which the military descended. When Captain Donovan first arrived in Vietnam in 1965, the war felt manageable and the soldiers were elite. Serving with the 101st Airborne Division—the “Screaming Eagles”—Donovan led professional paratroopers who had volunteered for service. Discipline was absolute, and the mission—search and destroy—was executed with surgical precision.

In those early years, desertion rates were below 2%, and operational readiness was at a staggering 97%. These were men who believed in the mission and trusted their leaders. As Lieutenant James McCarthy wrote home at the time, “These are the finest soldiers I’ve ever served with.” But this professional backbone was about to be replaced by a force that the system wasn’t designed to handle.

1968: The Breaking Point and the Draft

By the time Donovan returned for his second tour in August 1968, the landscape had shifted violently. The Tet Offensive had shattered the illusion of an easy victory, and the troop strength had swelled to over half a million. Crucially, the military was no longer a volunteer force; it was powered by the draft. Fewer than 30% of the soldiers were volunteers.

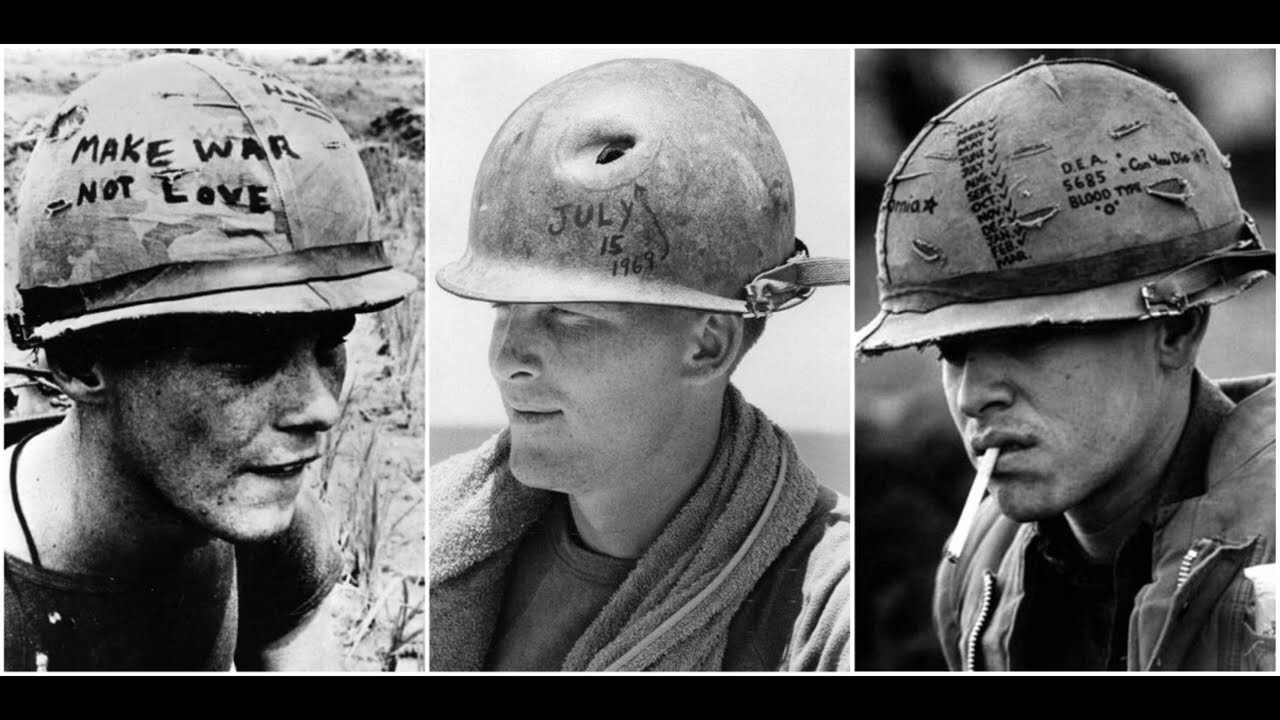

Donovan’s new unit was a collection of 19 and 20-year-old conscripts who wore peace symbols on their helmets and viewed the war with a cynical, exhausted skepticism. They had watched territory be seized and then abandoned five times over. They had seen their friends die for hills that were given back the next week. When ordered to advance, they didn’t charge; they moved so slowly that the mission became impossible—a tactic known as “search and avoid.”

The Epidemic of Fragging

The tension between career officers (derogatorily called “lifers”) and the draftees turned lethal. The first fragging incident Donovan encountered involved a platoon leader, Lieutenant William Patterson, who had been pushing his men for stricter discipline and cracking down on marijuana use. At 2:17 a.m., a grenade was rolled under his bunk.

Patterson survived, but he lost a leg. When Donovan addressed the company the next day, a voice from the back ranks shouted, “Maybe he shouldn’t have been such an asshole.” The ensuing laughter from the troops signaled a terrifying truth: the chain of command had lost the consent of the governed.

By 1971, the crisis was so acute that officers stopped sleeping in their assigned quarters, rotating locations randomly to avoid being targeted. Many wore body armor and kept loaded pistols next to their beds—not to protect themselves from the Viet Cong, but from their own men.

Systemic Collapse: Heroin, Desertion, and Refusal

Fragging was merely the tip of the iceberg. By 1970, an estimated 35,000 American soldiers were regular heroin users. The drug was pure, cheap, and ubiquitous in Saigon. In some units, half the men were high during morning formations. Officers often looked the other way; if they discharged every addict, they wouldn’t have enough bodies to hold the perimeter.

“Combat refusal” also became a common, albeit whispered, reality. Entire companies would simply refuse to move into fortified enemy positions. In August 1969, Alpha Company of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade refused a direct order to advance. The Army, terrified that prosecuting 140 men would trigger a mass mutiny, simply sent a different unit and buried the incident.

In 1971, the statistics of the internal war were staggering. Desertion rates exceeded 70 per 1,000 soldiers. In 1970 alone, 65,423 soldiers deserted—roughly 180 men every single day. The Army was conducting 213,000 courts-martial a year, meaning one in six soldiers faced military justice charges.

The Loss of Purpose

The final blow to morale was the realization that the war was being fought without a clear objective. The “short-timer” phenomenon—where soldiers in their last two months of a one-year tour became functionally useless—destroyed unit cohesion. Unlike World War II, where units trained and fought together for years, Vietnam soldiers rotated in and out as individuals. A company was no longer a family; it was a “bus station” of strangers waiting for their sentence to end.

As a Catholic chaplain, Father Michael O’Brien, told Donovan in 1971: “Leadership requires consent. These men have withdrawn their consent from the entire system. You can’t lead them; you can only try to keep them alive until this ends.”

The Rebuilding and the Lesson

Brian Donovan resigned his commission as a Major in 1972, unable to continue a career he felt had become “crisis management of a system destroying itself.” He was part of a “hemorrhage” of junior officers—the Army’s officer corps shrank by 30,000 positions in just four years.

The rebuilding effort led by General Creighton Abrams after the war resulted in the elimination of the draft and the creation of an all-volunteer force. The military recognized that morale isn’t an “extra”—it is the foundation of power.

The story of the fragging epidemic serves as a timeless journalistic warning. It proves that no matter how sophisticated the technology or overwhelming the firepower, a system cannot function when the humans inside it stop believing in the cause. When you treat people as interchangeable parts and ask them to die for a “body count” they don’t understand, they don’t just stop fighting the enemy—they turn their weapons on the system that sent them there.

Captain Donovan’s blood-stained grenade pin remains a silent testament to the moment the world’s greatest military was defeated, not by a foreign army, but by the math of human psychology.a