Hunter Tracks 2,000lb Bear, BUT He Finds a BIGFOOT NEST – Sasquatch Encounter

Kodiak Shadows

Chapter One: The Call

I never expected to be the one to stumble upon something that would unravel everything I thought I knew about the wild. When the phone rang that morning, I assumed it was just another routine call from wildlife services—a bear sighting, maybe an aggressive animal to relocate or, if necessary, put down. In Alaska, such calls came often enough that the edge in the dispatcher’s voice didn’t usually faze me. But this time, something was different. The farmer on the eastern side of Kodiak Island sounded terrified, his words clipped and shaky as he described what had happened to his cattle the night before. One of his steers had been killed and dragged into the forest. He claimed he’d fired twice at the creature, certain he’d hit it at least once. He was adamant: it was a bear, a massive Kodiak, maybe close to two thousand pounds, judging by the sheer force it had displayed.

.

.

.

By law, any incident involving a bear attacking livestock had to be reported immediately, but this farmer wanted more than paperwork. He wanted someone to track down the beast and make sure it could never threaten his herd again. He described weeks of stalking—heavy footsteps circling his land at night, strange noises echoing through the dark, and enormous tracks left behind. His voice trembled, and I knew right then that something was off. Farmers in Alaska don’t scare easily. They live on the edge of the wilderness, facing its dangers daily. If he was rattled, the situation demanded attention.

I’d been with wildlife services for over fifteen years, starting straight out of college with a degree in wildlife biology and a minor in ecology. Some of my classmates dreamed of research labs or university lectures; I craved the field—the raw, unpredictable wild. There’s a purity to it, a reality you can’t replicate in textbooks or classrooms. Over the years, I’d tracked everything Alaska could throw at me: black bears, brown bears, Kodiak giants, mountain lions, wolves, even moose that had wandered too close to people. Each species had its own logic, its own patterns. Bears, for instance, were usually straightforward—driven by hunger, opportunistic, not malicious. A bear that broke into cabins or preyed on livestock had simply learned that humans meant easy food. Relocate them far enough away, and the problem was usually solved.

But Kodiak bears are something else entirely. The largest of the brown bears, adult males can weigh anywhere from twelve hundred to sixteen hundred pounds, with some pushing two thousand. They’re powerful enough to flip an eight-hundred-pound boulder searching for food, fast enough to run down a caribou. Yet, despite their size, they rarely go out of their way to attack humans. Most incidents happen when a bear is startled or a mother is protecting her cubs. Give them space and respect, and they’ll leave you alone.

That’s why the farmer’s story unsettled me. An adult Kodiak stalking a farm, killing livestock, and not fleeing when shot at? That wasn’t typical. Still, I’d dealt with unusual cases before—a black bear that developed a taste for trash and broke into five cabins in two weeks, refusing to retreat even when confronted. It took me three days to track him down and relocate him, but the problem was solved. So, while the Kodiak situation was concerning, I wasn’t overly worried. I packed my gear—tranquilizer rifle, regular rifle, tracking kit, GPS, radio, water, and emergency supplies—and drove out.

The journey to the farm took an hour and a half. Kodiak Island is massive, over thirty-five hundred square miles, much of it untouched wilderness. The road was little more than a dirt track winding through dense forest, mountains looming in the distance. When I arrived, the isolation was palpable. The farm was surrounded on three sides by thick woods, mountains rising behind it, a few outbuildings, a barn, cattle fencing, and a small house—the only signs of civilization for miles.

The farmer met me on his porch. He was in his fifties, weathered and strong, the kind of man whose hands told stories of decades spent working outdoors. But those hands shook as he greeted me, and his eyes darted nervously to the treeline. People who live this far out don’t spook easily. If he was this rattled, I knew I needed to pay attention.

Chapter Two: The Trail

He led me to the attack site without much conversation. We crossed the property, passed the barn, and reached the edge where grassland met forest. The scene was brutal—grass ripped out in clumps, deep furrows gouged into the earth, drag marks leading straight into the trees. The steer’s carcass lay at the forest’s edge, a six-hundred-pound animal dragged a hundred yards from the field. Blood was everywhere, pooled in the grass, smeared on bushes, trailing into the woods in thick, dark streaks.

I knelt to examine the remains, and immediately, something felt off. The bite marks weren’t right. Bears have a distinctive kill pattern—powerful, methodical, usually going for the throat or belly. These wounds were different. The flesh was shredded, torn in a frenzy, not punctured. It was chaotic, almost desperate.

The farmer recounted the previous evening. Around dusk, he’d heard his cattle panicking, grabbed his rifle, and ran outside. He saw something dragging his steer toward the forest—a hulking figure, far larger than any bear he’d ever seen. Thirty years on Kodiak, he knew bears, but this was different. He fired twice, saw it stumble, but it didn’t drop the steer or flee. It just kept dragging the carcass, vanishing into the trees. The way it moved, the sounds it made, none of it felt natural. He’d locked himself inside and called wildlife services at first light.

He described weeks of strange activity—heavy footsteps at night, deep grunting noises unlike any bear, massive tracks near his barn and water trough, circling his house. The tracks were elongated, lacking claw marks, puzzling even his neighbor. But without an actual attack, wildlife services wouldn’t act. He’d lived with it, growing more anxious until the attack finally happened.

Listening to his account, I was unsettled. Stalking behavior, strange sounds, unusual tracks—none of it fit the profile of a typical Kodiak bear. Animals can act unpredictably, especially if sick or injured, but this was something else. Still, I chalked it up to an unusually bold bear, perhaps a big male that had lost its fear of humans.

I radioed wildlife services, informing them I was beginning the track. Standard protocol: log my position, check in every two hours. If I missed a check-in, they’d send a search party. Safety first in remote areas.

The blood trail into the forest was obvious—thick splatters on undergrowth, smeared tree trunks, drag marks, and enormous footprints in the soft earth. I expected the trail to be short; an animal shot twice and bleeding heavily shouldn’t go far. A mile, maybe two. But I walked for hours, and the trail never faded. If anything, the blood increased. Whatever I was tracking should have been dead several times over.

The forest grew denser—old-growth spruce and hemlock blocking sunlight, understory thick with ferns and devil’s club. Progress was slow, every step requiring caution. What struck me most was the silence. Normally, the woods would be alive with birds, squirrels, the rustle of small animals. Here, there was nothing. Just an oppressive silence, broken only by my footsteps and breathing. It was the kind of quiet that falls when every prey animal has gone to ground, hiding from a predator.

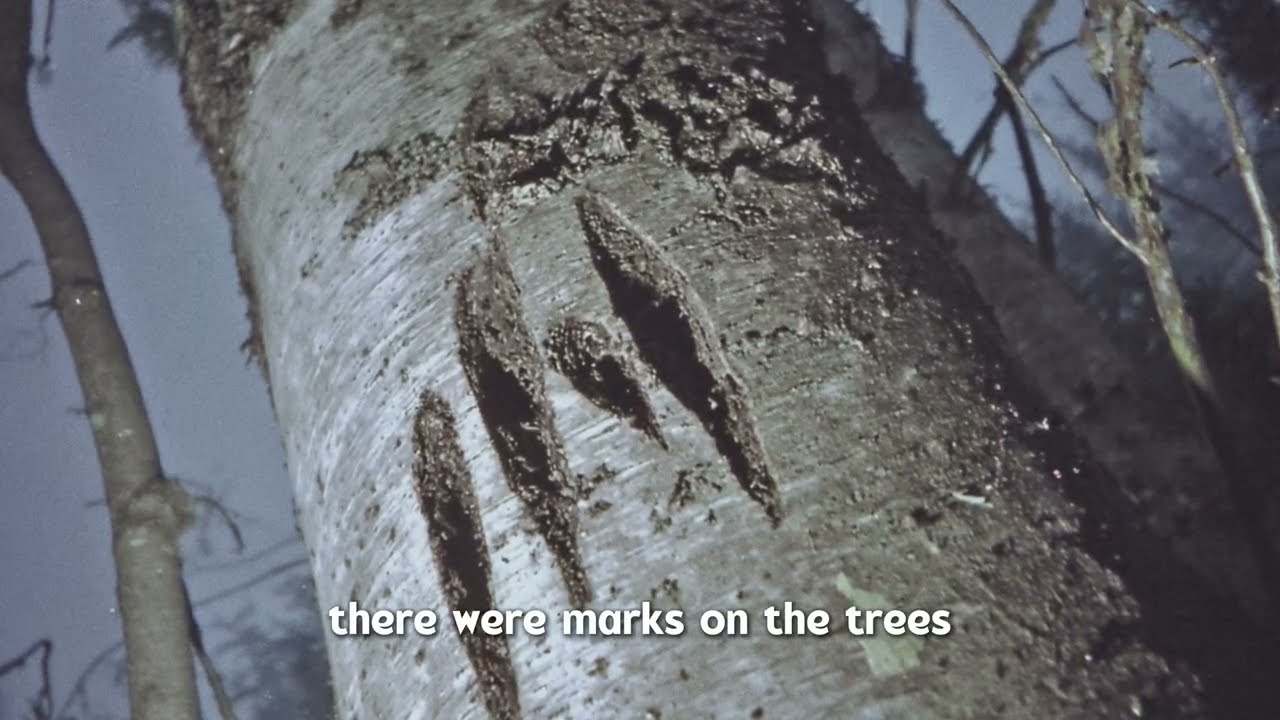

After three hours, I noticed more signs that didn’t make sense. Gouges in the bark, fresh enough that sap still seeped out, but far higher than any bear could reach—ten or twelve feet up. Bear claws leave neat, parallel grooves. These were chaotic, random, as if something had raked its claws down the trunk in frustration.

Crossing a stream, I found footprints in the mud that stopped me cold. They were enormous—eighteen inches long, eight wide—but the shape was wrong for a bear. Five thick, splayed toes, almost prehensile, an elongated pad, no claw marks. Disturbingly humanlike, but impossibly large. I photographed the prints, needing proof for myself as much as for anyone else. My mind raced for rational explanations—maybe the mud distorted a bear’s print, maybe overlapping tracks. But these were clean, distinct, upright impressions.

I radioed my second check-in, keeping my voice steady despite my shaking hands. I reported the heavy blood loss, expecting to locate the animal soon, but omitted the strange tracks and marks. What could I say? That I was following something leaving human-shaped footprints the size of snowshoes? They’d think I was joking or delusional.

The trail climbed toward the mountains, terrain turning rockier, the air growing colder. After four hours, my legs burned from the hike. I stopped for water, checking my bearings. The blood trail remained heavy, but now I saw something else—a crude structure off the trail, made from bent saplings and thick branches, arranged in a rough dome. It looked like a shelter, but no human had built it. Some branches were six inches thick, snapped clean. Whatever made this was incredibly strong, and the construction showed intention, not randomness.

I approached cautiously, hand on my sidearm. Up close, the shelter was big enough for something large—eight feet across, six high. Inside, dried grass and moss formed a rough bed, and the smell was overpowering—musky, pungent, like wet dog mixed with rot and something chemical. It was so strong it made my eyes water. Bears have a scent, but this was different, almost like territory marking.

Something was building shelters, creating nests, showing complex behavior. That wasn’t bear behavior.

Chapter Three: The Discovery

Every instinct screamed at me to turn back, but I’d come too far, invested too many hours. I thought of the farmer, alone on his property, afraid. I couldn’t just abandon the track. I photographed the shelter, marked its GPS location, and pressed on.

The sun dipped lower, and I realized I’d been tracking for over five hours, covering seven or eight miles of rough terrain. My water was low, and I considered camping overnight if I didn’t find the creature soon. The thought of spending the night out here, with whatever was making those tracks nearby, made my stomach clench.

The forest opened into a clearing at the base of a sheer rock face, the mountain rising two hundred feet, all vertical stone and sparse vegetation. The clearing was forty yards across, grass yellowed and sparse, rocks scattered about. In the middle lay a dark shape, at first just a boulder or fallen tree. But as I drew closer, the form resolved into something that set my heart hammering.

It was a body—a massive body covered in dark, matted hair, lying on its side, motionless. I approached slowly, tranquilizer rifle raised though the creature wasn’t moving. As I got closer, the details became clearer, and each one made less sense.

This was no bear. It was bipedal, built to walk upright, legs thick and muscular, bent at the knee even in death. The torso was barrel-shaped, broader than any human’s, the arms long and powerful, muscles visible beneath the hair. I circled to see its head, and that’s when I knew for certain—this was no animal I’d ever studied. The face was flat, not elongated like a bear’s muzzle, the skull conical, rising to a peaked crown. The nose was broad and flat, the jaw heavy and pronounced. There was something almost human about the proportions, but scaled up and distorted, as if some evolutionary cousin had diverged from our family tree millions of years ago.

The hands were enormous, each finger as thick as my wrist, with opposable thumbs. The palms were broad and flat, the fingers long and capable of grasping. These weren’t paws; they were hands, designed for manipulation, but built on a scale that defied reason.

I saw the bullet wounds—one in the upper torso, one in the abdomen. The farmer had hit his target both times. The fur around the wounds was matted with dried blood, and the creature had bled out during its long trek through the forest. The body was still slightly warm, steam rising in the cool mountain air. It had died recently.

I stood there for what felt like forever, staring at the impossible. My scientific training, years of experience, everything I knew about zoology and wildlife biology—none of it prepared me for this. This creature shouldn’t exist. And yet, here it was, dead at my feet.

Bigfoot. Sasquatch. Whatever name you chose, this was it. I’d heard the stories, the legends, the supposed sightings, the grainy photos and shaky videos. I’d dismissed them all as folklore, misidentification, imagination. But this—this was undeniable proof that something had eluded science.

I reached for my radio to call it in, and that’s when I heard the sound—a low, deep, rumbling grunt that seemed to come from the ground itself. Then another, and another. I froze, hand halfway to my radio, every muscle tensed. The sounds were coming from nearby, getting closer.

I turned, scanning the clearing, and saw the cave—fifty yards away, a dark opening in the rock face I’d missed before. Something was moving inside. Shadows shifted, heavy footsteps echoed on stone. Then one of them stepped out into the light.

Chapter Four: The Encounter

The creature was massive, easily as large as the dead one on the ground. Its hair was dark brown, almost black, and it moved on two legs with a strange, loping gait, long arms swinging at its sides. It walked directly toward the body, attention focused on its fallen companion. It hadn’t seen me yet—I was downwind, frozen in place, barely breathing.

Then another emerged from the cave, and another. Four in total, each similar in size, all moving toward the dead creature, vocalizations low and mournful. They gathered around the body, their sounds changing, almost like grief. One reached down, touching the wounds with surprising gentleness. They were mourning.

The realization hit me—this wasn’t just a lone anomaly. This was a group, a family, with a den, social structure, complex behaviors. This was a species, a population that had managed to avoid detection by living in the most remote corners of the wilderness. And I had stumbled into their home, standing next to their dead family member.

I began backing away, inch by inch, avoiding sudden movements. I was thirty yards from the treeline. If I could reach it, I might escape, call for help. My tranquilizer rifle was useless—three darts, four creatures, and even if I managed to hit one, the others would be on me before I could reload.

I’d made it ten yards when one of them stopped. It had been crouched over the body, but now it straightened to its full height—eight and a half, maybe nine feet tall. Its head tilted, nostrils flared, testing the wind. Then its gaze locked onto me.

For a moment, we stared at each other across the clearing. Its eyes were small and dark, set deep in its skull, but the intelligence there was unmistakable. This wasn’t a dumb animal acting on instinct. It was thinking, assessing, making decisions. I saw the moment it recognized me as a threat. The others noticed, turning to look. Four sets of eyes fixed on me, and the clearing went silent.

The largest one—a massive male with shoulders that could tear a tree in half—opened its mouth and roared. The sound was like nothing I’d ever heard, deep and booming, resonating in my chest, setting off every primal alarm. It was a sound that said danger, predator, run or die.

So I ran. I bolted for the treeline, all thoughts of stealth forgotten. I heard them coming—the ground shook with their footsteps, branches snapped, that roar echoed again and again. I crashed into the forest, boots slipping on rocks, branches whipping my face. I didn’t look back. Looking back meant slowing down, and slowing down meant death.

The forest was dense, trees close together, and I used every bit of that to my advantage—ducking under branches, weaving between trunks, leaping over logs. They were faster than I’d imagined, each footfall thunderous, closing the gap. But their size worked against them; they couldn’t maneuver through tight spaces as easily as I could. Every time I found a narrow gap, I took it, forcing them to adjust their path.

My lungs burned, legs screamed, but I couldn’t slow down. Sometimes, I heard them close enough to catch their breathing—deep, raspy huffs that sounded almost like words. Then I realized—they weren’t just chasing me, they were communicating, coordinating, trying to flank me and cut off my escape.

I changed tactics, doubling back, taking unexpected turns, using every trick I’d learned to confuse my pursuers. I reached a stream, ran upstream for two hundred yards, hoping the water would disrupt my scent. The cold soaked my boots, but I didn’t care. Water makes tracking harder, and even a few minutes’ advantage might save me.

I climbed out on the opposite bank, took cover behind a massive cedar, chest heaving, heart pounding. For a moment, silence. Then their calls echoed, more spread out, searching. I checked my GPS—six miles from the farm, mostly downhill if I kept the right heading.

Chapter Five: The Escape

I moved quietly, unable to keep up the panicked sprint. From cover to cover, pausing to listen. Sometimes I heard them searching, sometimes silence, which was worse. I slid down a ravine, crouched behind a boulder, listening as one moved along the ridge above, tracking me. I pressed on, pushing through blackberry brambles that tore at my skin, but slowed them down. On the other side, I tossed my jacket—heavy with my scent—in the opposite direction, hoping to create a false trail.

I kept moving, staying aware of wind direction to keep my scent from reaching them. The terrain grew familiar; I was nearing the farm. Hope gave me energy, but I forced myself to stay careful, never exposing myself in open areas.

Then, footsteps ahead. I dove behind a boulder, pressing myself against the cold stone. Through a gap, I saw one of the creatures, walking methodically, head swinging, searching. It came within twenty feet, sniffed the air, nostrils flared. I held my breath, heart pounding so loud I thought it would give me away. It stepped closer, then turned away, moving off. The boulder and wind direction had saved me.

I moved slower now, every step deliberate, avoiding dry branches, sticking to soft ground. The sun touched the horizon—forty-five minutes of light left. I couldn’t be caught out here in the dark; they’d have the advantage.

I reached a ridge and looked down—half a mile below, the forest ended and open farmland began. The farmhouse was visible, lights glowing. Relief flooded me, but I wasn’t safe yet. Half a mile of forest still separated me from safety.

I started down the slope, moving quickly but carefully, never losing sight of the farmhouse. The forest thinned, the undergrowth less dense. I was close—maybe a quarter mile from the edge. Then I heard them again, grunting calls behind me, higher up the slope. They were still searching, but I was ahead. I broke into a run, exhaustion forgotten, crashing through the last of the undergrowth, bursting out into the open field.

The grass was waist-high, but I plowed through, eyes locked on the farmhouse. I glanced back—the creatures were at the treeline, four massive shapes silhouetted against the darkening sky, watching me. They didn’t chase, just stood and stared.

I ran harder than ever, lungs on fire, legs rubber. The farmhouse grew closer, lights brighter. I reached the barnyard, nearly collapsing. The farmer saw me, rushed out, eyes wide at my torn clothes, scratched skin, and wild expression. I grabbed his arm, gasping that we needed to leave, now. He saw the terror in my eyes and didn’t argue, running for his truck.

As he fumbled with the keys, I looked back—the creatures were moving slowly across the field, two hundred yards away and closing. The farmer saw them, went pale, hands shaking as he started the truck. Gravel sprayed as we tore down the driveway, the truck fishtailing before finding traction.

I watched out the back window. The creatures reached the edge of the farmyard, stood where we’d been moments before, watching us leave. Their forms grew smaller, swallowed by the darkness.

We drove in silence, the farmer’s knuckles white on the wheel, jaw clenched. I tried to process what had happened, slow my breathing, convince myself it was real. The scratches on my arms, the ache in my legs, the memory of those creatures—undeniably real.

At the wildlife services office, I recounted everything—the blood trail, the tracks, the shelter, the body, the others, the chase, their coordination. The supervisor listened, skeptical, exchanging glances with another officer. He asked for evidence. I showed my photos—the prints, the claw marks, the shelter. They examined them, asked about injuries. I showed my torn clothes and bleeding arms.

I filled out a formal report, hands trembling, handwriting barely legible. The supervisor said they’d send a team at first light, heavily armed, taking precautions. Afterward, I sat in the office, replaying every moment. The farmer left to stay with relatives, refusing to return until it was resolved. I was alone with my thoughts.

Would the search party find anything? Would the body still be there, or would the creatures have moved it, erased all evidence? If they found something, what then? How do you tell the world that everything they believed about the natural world is incomplete?

I didn’t wait to find out. I filed my report, gave them all I had, and left. I couldn’t stay on that island. Every sound made me jump, every shadow reminded me of those eyes. I caught the first ferry off the island and haven’t returned. I don’t know what the search party found. Maybe they sent a report, but I never opened it. Part of me doesn’t want to know. Part of me needs it to remain a mystery.

Sometimes I wonder if they found the body, confirmed something unexplainable. Other times, I imagine they found nothing, the creatures having removed all evidence. Mostly, I try not to think about it.

What haunts me most is the intelligence I saw—the way they communicated, grieved, coordinated. These weren’t dumb animals. They were thinking, feeling beings with complex social structures. We’ve dismissed them as myth, folklore, the delusions of unreliable witnesses. How many other impossible things are out there, hiding in the world’s remote corners, ignored by science?

I’m often asked if I’d go back, join another expedition, document these creatures properly. My answer is always the same: Absolutely not. Some things in the wilderness are better left undiscovered, some mysteries unsolved. Once you’ve seen them, once you know they’re real, it changes you. It changes how you see the world, how you understand your place in it.

I used to be confident in my understanding of nature. Fifteen years studying, working, learning its rhythms. But now I know that understanding was incomplete. There are things we don’t know, things hiding in the shadows. And most of the time, that’s probably for the best.

I don’t go into the wilderness anymore—not alone, not far from my vehicle, never out of cell range. Some might call it cowardly, but they haven’t seen what I’ve seen. They haven’t had their reality shattered in a few terrifying hours.

So that’s my story. That’s what happened on Kodiak Island when I was sent to track down an aggressive bear. I found something else—something impossible, something that shouldn’t exist but does. I survived to tell about it. Sometimes I’m not sure if that’s a blessing or a curse. Because now I live with the knowledge that our understanding of the world is incomplete, that there are mysteries out there we haven’t solved, creatures we haven’t cataloged, impossibilities that are somehow real.

Some things in the wilderness are better left undiscovered. I know that now. I learned it the hard way. And I hope you never have to learn it the way I did.

For more stories like this, keep searching the shadows. Sometimes, the truth is stranger than fiction.