October 31st, 1966. 1500 hours on the Mong River, Republic of Vietnam. Boats winds mate first class. James Elliot Williams couldn’t hide the tension in his jaw as he scanned the muddy brown water through the spray streaked windscreen of patrol boat River 105. The 36-year-old South Carolina native commanding his fiberglass gunboat and one companion craft through an isolated stretch of the delta watch two sampans materialized from the river mist ahead.

Intelligence had reported Vietkong activity in this sector. What Williams didn’t know, what none of the fourman crew aboard PBR 105 could have imagined, was that they were about to stumble into the largest enemy staging area encountered by American Riverine forces to that date. Within minutes, those two innocuous looking sampons would lead them into a three-hour battle against hundreds of Vietkong fighters, dozens of armed vessels, and fortified positions on both riverbanks.

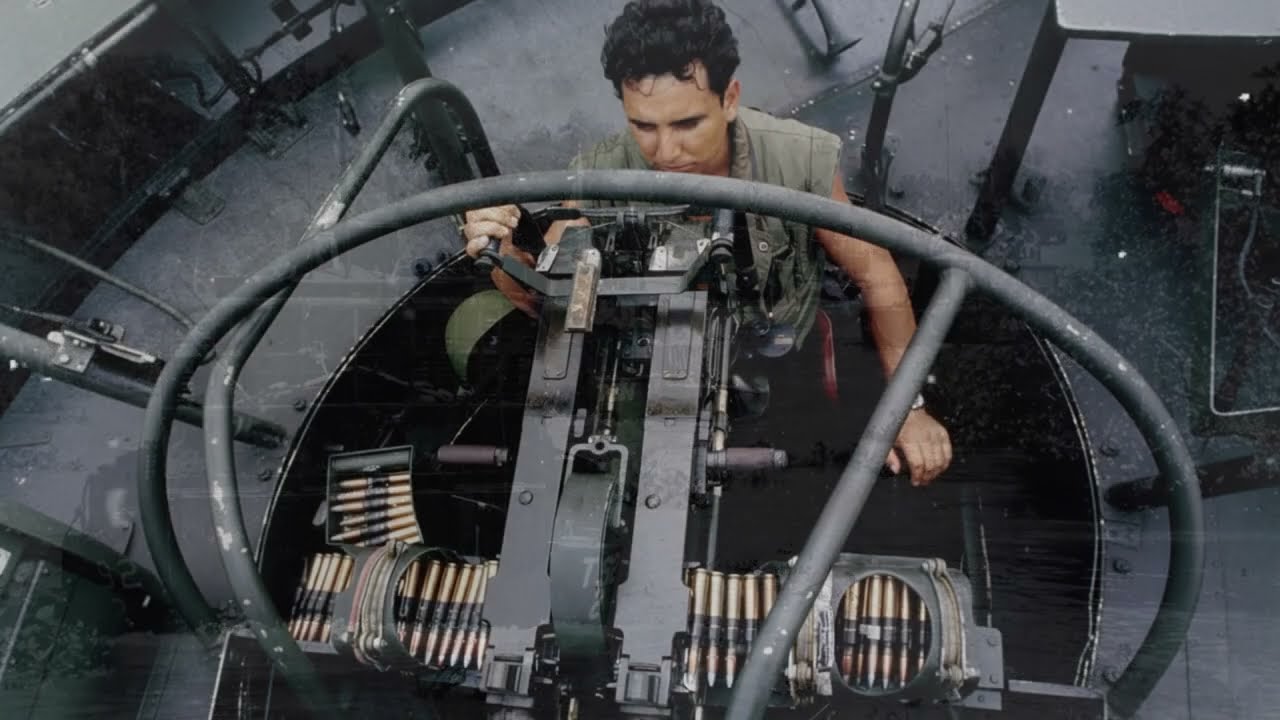

When the Sampons opened fire without warning, Williams ordered immediate return fire. The twin 50 caliber machine guns in the forward turret hammering out their distinctive thunder. One Sam pen disintegrated under the onslaught. The other fled desperately into a narrow canal, and Williams made the decision that would change everything.

“Follow them,” he ordered, and the two American patrol boats surged forward at 30 knots, their jacuzzi water jet drives churning the brown water white. The fleeing san led them straight into hell. As the PBRs rounded the bend into the canal, the jungle exploded with muzzle flashes. Automatic weapons fire laced the water from concealed positions along both banks.

Rocket propelled grenades stre across the narrow waterway, their distinctive whoosh audible even over the roar of engines and guns. Williams found himself staring at a sight that should have meant certain death. two large junks and at least eight senes packed with Vietkong fighters, shore-based machine gun positions, RPG teams, an entire battalionized force caught in the middle of a major resupply operation.

There were no exit ramps on the Meong River, no way to turn around in the narrow canal without exposing the vulnerable stern to withering fire. Williams made the only choice that offered survival. He ordered both boats to attack at full throttle, charging directly into the center of the enemy formation.

The mathematics of that decision defied every tactical manual. Two American patrol boats, eight sailors total, against hundreds of enemy fighters with prepared positions and overwhelming firepower. But Williams understood something the Vietkong didn’t. The PBR’s speed, the shocking audacity of a frontal assault, the concentrated firepower of synchronized machine guns.

These created a kind of mechanical violence that could shatter even a prepared ambush through sheer disbelieving chaos. The Twin 50s opened up, each gun spitting out 550 rounds per minute. The single 50 in the aft position joined the chorus. The M60 machine guns on the sides added their voices. The boats zigzagged through the kill zone at speeds approaching 40 mph.

Their wakes throwing up walls of water. Their guns never silent. Enemy fighters along the banks couldn’t track the racing targets. Those aboard the Samans found themselves caught in crossfires as the Americans wo between vessels. The concentrated streams of heavy machine gun fire ripping through wooden hulls like tissue paper. Sampons exploded.

Junks burst into flames. The Vietkong’s own positions became targets as rounds meant for the Americans struck their comrades across the narrow waterway. The American boats punched through the first staging area, rounded another bend, and found a second concentration of enemy vessels.

No way back, no way around, only through. Williams called for helicopter support and continued the attack, his southern draw calm on the radio, even as his boat shuttered under the impact of enemy rounds. The UH1B Hueies of Navy helicopter attack squadron 3, the Seawolves, arrived as darkness began to fall. Williams turned on his search lights, deliberately making himself a target to expose enemy positions for the gunships.

For 3 hours, the battle raged. When it ended, more than 65 enemy vessels lay destroyed or damaged. Conservative estimates placed enemy casualties at over 200 killed, though the true number would never be known. The two American patrol boats, riddled with bullet holes, limped back to base. Not one American sailor had been killed.

Seven months later, President Lyndon Johnson would present James Williams with the Medal of Honor in the newly dedicated Hall of Heroes at the Pentagon. The citation would speak of conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. But Williams action that Halloween afternoon represented something larger than individual heroism.

It was validation of a concept that military planners and river veterans of previous wars had questioned. The idea that the United States Navy, an institution built around deepwater capital ships and carrier battle groups, could fight and win in the muddy, treacherous inland waterways of Southeast Asia. That small boats with minimal armor could dominate an environment where every bend held potential ambush, where mines could be planted in minutes, where the enemy knew every canal and creek.

The Brownwater Navy had been born from desperation, mocked by traditional Navy men, and written off by commanders who couldn’t imagine how patrol boats would matter in a guerilla war. Within two years, it would become one of the most successful naval operations in American military history, strangling Vietkong supply lines, disrupting enemy operations across thousands of square miles of waterways, and transforming the strategic situation in South Vietnam’s most populous region.

This is the story of how laughingstocks became legends. How fiberglass, boats dismissed as toys became the most feared weapons in the Meong Delta. How sailors trained for deep ocean warfare learned to fight in rivers, measured in feet instead of fathoms. How industrial capacity, tactical innovation, and raw courage combined to seize control of Vietnam’s liquid highways from an enemy that had owned them for decades.

The Meong Delta sprawls across 15,000 square miles of southern Vietnam. a vast aluvial plane where the Mong River fragments into a maze of channels, canals, and waterways before emptying into the South China Sea. In 1965, this region housed nearly 8 million people, produced 3/4 of South Vietnam’s rice, and contained the economic lifeline connecting Saigon to the agricultural heartland.

It was also quite literally unnavigable by conventional military force. The rainy season transformed it into an inland sea where roads became rivers and the distinction between land and water disappeared. The dry season revealed a landscape of rice patties dissected by thousands of miles of natural and man-made waterways.

The plane of reeds, a vast marsh in the northwest delta, featured water depths between 1 and 6 feet year round. The populated rice growing regions contained the densest concentration of humanity, crisscrossed by major rivers like the Bassac and branches of the Mikong. The Rangsat Special Zone, a 25mi stretch of mangrove swamps surrounding the shipping channel to Saigon, earned the nickname Forest of Assassins for good reason.

For the Vietkong, this liquid landscape was both fortress and highway. Samans could move troops, weapons, and supplies through narrow canals where vehicles couldn’t follow. River traffic couldn’t be distinguished from civilian movement until weapons appeared. Traditional military operations required solid ground, but solid ground in the delta was measured in hectares scattered among waterways.

By early 1965, the situation had become critical. Vietkong forces controlled major portions of the delta, taxing river traffic at organized checkpoints, moving battalions along waterways without interference, and interdicting food supplies to Saigon. South Vietnamese river forces equipped with castoff craft inherited from the French Indo-China War proved inadequate.

Their boats were slow, underarmmed, and primarily used for fing Army of the Republic of Vietnam troops rather than actively contesting Vietkong control. The Americans faced a fundamental problem. How do you fight a war where the battlefield is water? The enemy appears indistinguishable from civilians until he starts shooting, and traditional naval power means nothing.

Aircraft carriers couldn’t patrol canals. Destroyers drew too much water. The conventional navy had no answer. The solution required thinking back to the last time American forces had fought extensively on inland waters. The Civil War when Union gunboats and converted river steamers had battled Confederate forces along the Mississippi and its tributaries.

In December 1965, the US Navy established the River Patrol Force and designated it Task Force 116. The operational name reflected the mission’s focus, Operation Game Warden, Stop Vietkong Infiltration on the waterways, protect commercial traffic, enforce night curfews, keep the rivers open.

The response from traditional Navy men ranged from skepticism to outright mockery. One senior officer reportedly observed that the Navy hadn’t fought on rivers since Ulissiz S. Grant was alive, and there was probably a good reason for that. The boats initially assigned to Game Warden did nothing to inspire confidence. Early operations relied on South Vietnamese river craft or modified World War II era landing craft, slow, ungainainely vessels that presented easy targets in narrow waterways.

Then in March 1966, the first 11 examples of a revolutionary new design arrived at Catllo Naval Base. The patrol boatine designation PBR. To traditional Navy eyes, it looked like a pleasure craft that had gotten lost on its way to a boat show. 31 ft long, fiberglass hull, powered by twin jacuzzi water jet pumps, more commonly found in recreational boats, drawing only 9 in of water when empty, allowing it to literally skim over sandbars that would ground conventional vessels.

Maximum speed 25 knots unloaded, approaching 40 knots with experienced crews pushing the limits. Ceramic armor plating covered critical areas. But the hull itself offered no protection against anything larger than small arms fire. The weapons package, however, told a different story about the PBR’s intentions.

Forward, a twin 50 caliber machine gun mount. aft, a single 50 caliber, an M60 machine gun on each side. Later versions added a Mark19 automatic grenade launcher. The boats carried enough ammunition to sustain combat for extended periods. Each 50 caliber gun could fire 550 rounds per minute. The M60s added another 350 rounds per minute each at convergence distance, typically set at 100 yards for river combat that created a cone of destruction that could saw through wooden vessels, shred foliage concealing positions, and deliver

suppressive fire that made return fire suicidal. The crew consisted of four sailors. A boat captain, typically a petty officer, first class, though as casualties mounted, secondass petty officers, and even lower ranks found themselves in command. An enginemen, a gunner’s mate, a seaman, all crossrained to assume any position if casualties occurred.

They operated in two boat patrols. Each boat providing cover for its partner, separated by roughly 4 to 600 yards, close enough to support each other with fire, far enough apart to minimize the effectiveness of ambushes and maximize radar coverage. The mission profile combined routine tedium with sudden explosive violence. 12-hour patrols, checking sampans and junks, verifying identification papers, searching for contraband weapons or rice beyond what civilians needed for personal consumption.

Then, with no warning, a burst of AK-47 fire from concealed positions along the bank. RPG rounds streaking across the water. The battle beginning before anyone had time to be afraid. Training for riverine operations took place at the Naval Inshore Operations Training Center on Mare Island, California, where the sloughs of the Sacramento River provided reasonable approximations of Meong Delta conditions.

Sailors learned small boat handling in currents and tight spaces, practiced with the weapon systems until they could clear jams blindfolded, studied first aid because medevac might be hours away, and absorb tactical lessons written in the blood of earlier patrols. They learned that in river combat, speed was armor. A stationary target died.

A boat that kept moving, jinking, changing course unpredictably, could survive fire that should have killed everyone aboard. They learned to read the water, the banks, the vegetation, to recognize good ambush positions, and preemptively hose them with fire rather than waiting for the enemy to reveal himself. They learned that rules of engagement were written by people who’d never been in a canal so narrow you could spit across it while enemy machine guns opened up from both sides.

The reality of game warden operations exceeded every pessimistic prediction. River section 531, one of the first units deployed, comprised 55 men and four officers. In the first 10 months of operations through March 1967, they suffered two killed and 26 wounded. On May 24th, 1967, those numbers exploded in a single action.

Two PBRs from section 531, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Donald Wit, were conducting a routine patrol near the Hamlong River when they encountered what they thought was standard harassment fire. The boats were drifting silently with engines off, radar running on batteries, hoping to catch Vietkong sampans attempting to cross the river.

As dawn broke, they entered a narrow channel between a three-mile long island and the riverbank. The Vietkong had been waiting for days. Up to 1,000 enemy soldiers had lined both banks and the island with machine gun positions, recoilless rifles, and RPG teams. Three miles of waterway transformed into a continuous ambush.

The coverbo took a recoilless rifle round amid ships, killing a South Vietnamese policeman instantly and blowing the after gunner overboard. The boat Cox Swain was wounded but kept the vessel moving, engines screaming. The forward gunner stayed at his twin 50s, reloading belt after belt even as the boat caught fire.

The lead boat carrying Lieutenant Wit absorbed even heavier punishment. The swain was wounded, the patrol officer wounded, the forward gunner blown over the side. Yet somehow both boats fought their way through, returning fire continuously, their speed and desperation carrying them past the prepared positions. The long way out meant running the gauntlet for three miles, 22 men wounded, the boats so shot up that mechanics later wondered how they’d stayed afloat.

But both boats made it back. The enemy’s carefully prepared ambush had failed because the PBRs could absorb punishment that would have destroyed conventional vessels and still keep fighting. By mid 1967, task force 116 had reached its peak strength. 2,32 personnel, 250 PBRs, seven mine sweeping boats, 31 other assorted craft.

The Navy established river divisions at strategic locations throughout the delta. River division 51 operated from Cantho and Bin Thui. Division 52 from Sadek, later Vinlong. Division 53 from Myth. Division 54 from Na Bay guarding the approaches to Saigon. Each division maintained aroundthe-clock patrols on assigned waterways, building local knowledge of currents, channels, villages, and Vietkong patterns.

The results began accumulating in ways that couldn’t be captured in simple kill counts or vessels destroyed. Vietkong defectors, the Hoy Chan Vienn, who surrendered under the Chiohoy amnesty program, consistently reported the same thing. PBR patrols had made water movement extraordinarily difficult. Units in the Delta sometimes went days without food because supplies couldn’t get through.

The organized taxation system the VC had established at canal junctions was disrupted. Moving a battalion across a major river now required elaborate planning and inevitable losses. One defector described a two-week period when his unit couldn’t cross the Namthon branch of the Mikong because PBR patrols appeared at unpredictable intervals.

They’d tried night crossings. They’d tried timing runs between patrol schedules. Every attempt resulted in losses until the operation was abandoned. The numbers told part of the story. In an average month by late 1967, game warden operations accounted for 40,000 vessel inspections, 2,000 Vietkong craft destroyed or captured, 1,400 enemy killed or detained, and countless supply movements interdicted.

The cost was high. From inception through final standown, Task Force 116 lost 200 sailors killed in action with 366 wounded. But the kill ratio, approximately 40 enemy killed for every American sailor lost, ranked among the highest achieved by US forces in Vietnam. The human cost generated two Medal of Honor recipients from Game Warden.

James Williams earned his on that October afternoon in 1966. Seaman David George Wle would receive his postumously for actions in March 199. Willlet was manning the forward gun position on PBR 124 during a Meong River patrol when the boat came under heavy fire. An enemy round struck the forward gunner, wounding him severely. Bule, though seriously wounded himself, left his protected position to render aid and drag the gunner to safety.

As he worked to save his shipmate, enemy fire struck him again. He continued administering first aid until another burst killed him. The 19-year-old from Massachusetts had enlisted at 17. His Medal of Honor citation spoke of extraordinary heroism and selfless devotion that would inspire generations of sailors.

But Game Warden was only half the equation. Controlling the rivers meant denying the Vietkong freedom of movement. It didn’t mean taking the fight to major enemy concentrations or conducting sustained offensive operations. For that, the Navy needed a different concept entirely. In June 1967, that concept became reality with the formal establishment of the Mobile Riverine Force.

The MRF represented the first time since the Civil War that the US Army operated an amphibious force living entirely afloat. It combined the second brigade of the 9inth Infantry Division with Navy Task Force 117, creating a 5,000man joint force capable of launching swift offensive operations throughout the delta. The concept drew inspiration from French Dasaw units, the division Naval Dao that had operated on Vietnamese rivers during the first Indo-China War.

The Americans expanded and modernized the idea, creating something unprecedented in American military history. The army component consisted initially of two infantry battalions from the second brigade. The third battalion 47th infantry regiment, the fourth battalion, 47th infantry regiment. Later other battalions would rotate through including mechanized and regular infantry.

Artillery batteries provided fire support. The entire brigade, roughly 1,500 combat troops plus support personnel, could deploy anywhere in the delta within 24 hours. The Navy component was task force 117, eventually comprising four river assault squadrons. Each squadron fielded an impressive array of specialized craft, all converted from World War II era landing craft or built specifically for riverine warfare.

52 armored troop carriers ATC’s called tangos by their crews. These converted LCM6 landing craft carried up to 40 troops each. Protected by ceramic armor and armed with 20 mm cannon, 50 caliber machine guns, and automatic grenade launchers, their boxy appearance inspired the nickname floating shoe boxes, but they could deliver an infantry platoon directly onto hostile beaches while suppressing enemy positions with overwhelming fire.

10 monitors, the riverine equivalent of gunboats. These modified landing craft mounted 40 mm cannon and 81 mm mortars, providing fire support that could devastate enemy positions. Their armor could withstand heavy machine gun fire and most RPG hits. Command and control boats, modified ATC’s fitted with advanced communications equipment served as floating headquarters for battalion and squadron commanders.

Assault support patrol boats, ASPBs, called Alpha Boats by Cruz, were the only original design built specifically for Vietnam. 50 ft long with my eye and in all steel hulls and aluminum super structures powered by twin 12cylinder diesels, giving them twice the speed of other riverine craft. They served as mind sweepers and escorts.

Their reinforced construction allowed them to survive mine detonations that would have destroyed other vessels. The floating base was equally impressive. Two self-propelled barrack ships, USS Benua and USS Colatin, modified with flight decks and air conditioning, each accommodating 800 troops. The Benua served as brigade and flotillaa flagship.

The Colatin received hospital facilities in late 1968 for treating lightly wounded soldiers. Additional barracks barges, repair ships, supply ships, and support vessels rounded out the Mobile Riverine base. The entire complex could move to new operating areas, establishing temporary anchorage on major rivers and launching operations from there.

But to truly understand the Mobile Riverine force, you had to see it on the ground, or rather on the water at Dong Tom. The name meant United Hearts and Minds in Vietnamese, chosen by General William West Morland to reflect American Vietnamese cooperation. The reality was more prosaic, but no less impressive. Dong Tam didn’t exist in August 1966 when dredging operations began.

It was created from nothing. 8 million cubic meters of sand and silt pumped from the Meong River bottom to fill 600 acres of rice patties 5 miles west of Mtho. Engineers raised the land between 5 and 10 ft above water level, making it proof against flooding during monsoons and high tides. By April 1967, Dong Tam occupied 12 square kilometers.

A C130 airirstrip allowed resupply flights. Boat basins provided birthing for one full river assault squadron. Repair facilities could handle major maintenance on the specialized craft. The army established the second brigade headquarters there along with infantry and artillery battalions. For the Vietnamese farmers whose patties had been transformed, it must have seemed like an alien city rising from their fields.

For the soldiers and sailors who would fight from Dongto, it became home. The first major operation launched from the completed base came on June 2nd, 1967, designated operation Coronado. The name would become legendary. Between June 1967 and July 1968, the mobile riverine force conducted 11 separate Coronado operations, transforming the strategic situation in the Meong Delta.

The operations followed a consistent pattern refined through trial and bloody error. Intelligence identified a Vietkong concentration or supply route. The mobile Riverine base would reposition to provide optimal access to the target area. In the pre-dawn darkness, infantry would board the ATC’s. The convoy would form up.

Monitors in the lead to suppress ambushes. ATC’s in column carrying the troops, ASPBS providing mind sweeping and flank security. The flotilla would move at six knots or less limited by the speed of the slowest vessels and the fierce currents in the lower delta. Helicopter gunships, the Seawolves, would orbit overhead.

Fixed wing closeair support remained on call. artillery batteries aboard barges or at fire support bases coordinated fire plans. Then at age hour, the chaos of an amphibious assault into hostile territory. The monitors would open up their 40mm cannon and mortars pounding suspected enemy positions. The ATC’s would beach simultaneously along the river or canal bank. Ramps would drop.

Infantry would pour out, often directly into enemy fire, secured by the ATC’s suppressive fire. Within minutes, an entire infantry company would be ashore and moving. The Riverine craft would maintain station, their weapons providing fire support that could be called in within seconds. If the infantry encountered heavy resistance, the boats could extract them under fire and reinsert at a different location.

This mobility drove Vietkong commanders to distraction. Their carefully prepared defenses in one village became useless when the Americans simply bypassed them and attacked from an unexpected direction. The first test of the MRF’s capabilities came on June 19th, 1967 during Operation Coronado in the area around APAC in Canok District, Longanne Province.

Alpha Company of the fourth battalion, 47th Infantry, marched into a prepared ambush. The Vietkong had chosen the ground well, entrenchments and bunkers positioned to create interlocking fields of fire. The lead platoon walked into a kill zone and was decimated within seconds. 28 soldiers from Alpha Company died that day.

The battalion suffered severe casualties overall. Charlie Company also took heavy losses attempting to relieve Alpha, but the MRF’s flexibility prevented complete disaster. Navy river assault craft repositioned, bringing in reinforcements from different angles. Artillery from the Mobile Riverine base plastered suspected enemy positions.

Helicopter gunships worked over the tree lines. The battle raged for two days, but the Vietkong couldn’t exploit their initial success because the Americans could bring overwhelming firepower to bear from multiple directions simultaneously. The lesson was brutal but clear. The MRF could operate in the enemy’s backyard, could take casualties that would have crippled conventional units, and could continue fighting because reinforcement and resupply were measured in minutes rather than hours or days.

By September 1967, the mobile Riverine Force was demonstrating capabilities that exceeded initial expectations. Operation Coronado 5 launched on September 15th near the Bahai River southwest of Saigon saw the enemy spring an ambush along a two-mile stretch of waterway. The Vietkong had prepared well, positioning heavy weapons to enilade the river.

Within minutes, half the boats in the convoy had been hit. Three sailors were killed and 77 wounded in the initial exchange. The brutality of the ambush should have destroyed the convoy. Instead, the specialized training and purpose-built craft allowed the Americans to fight through. The monitors laid down suppressive fire that forced enemy gunners to take cover.

The ATVs, their ceramic armor proving its worth, continued moving even when riddled with bullet holes. The ASPBs, arriving during Coronado 5 for their first combat test, demonstrated their value by leading boats through the kill zone at speeds the Vietkong hadn’t anticipated. More casualties came days later in another ambush.

Six more men killed or wounded. Yet the MRF continued operations, trapping elements of the Vietkong 263rd and 514th Main force battalions in October and inflicting 173 casualties. The mathematics of attrition worked both ways. The Vietkong could ambush American forces and inflict painful casualties, but they couldn’t win a sustained engagement because American industrial might could replace losses overnight.

While Vietkong replacements took months to train and infiltrate, weapons that proved particularly effective in riverine warfare included innovations adapted from necessity. Flamethrowers mounted on ATC’s or used as manportable weapons could clear bunkers and fortified positions. Fire arrows, literally arrows wrapped in petroleum soaked rags and ignited could set pans and structures ablaze from safe distances.

Water cannons blasting high pressure streams could erode earthn fortifications or disperse enemy concentrations in confined spaces. The ingenuity extended to placing M132 flame configured armored personnel carriers inside ATC’s, creating mobile fortified flamethrowers that could incinerate defensive positions without exposing infantry to direct fire.

The true test of the Mobile River force came during the Tetto offensive in January and February 1968. The largest coordinated enemy attack of the war saw Vietkong and North Vietnamese army units attack cities and towns throughout South Vietnam simultaneously. The communists strategy relied on using civilians as shields in urban warfare, believing American firepower would be constrained.

In the Meong Delta, the communists attacked 64 district capitals. The defense of the Delta fell primarily on American Riverine units and elements of the 9inth Infantry Division. More than half of South Vietnamese forces were on leave for the Tet holiday, leaving skeleton crews to defend critical positions. The Riverine fighters became the emergency response force.

When mytho came under attack, PBR units and mobile Riverine Force craft fought their way into the city, providing fire support and evacuating civilians. At Ben Trey, Riverine infantry conducted house-to-house fighting while Navy craft blockaded waterways to prevent enemy reinforcement. Chowok, Travin, Cantho, all defended with critical assistance from Brownwater Navy units.

At Vinlong, the Vietkong actually overran the PBR base, forcing defenders to withdraw to USS Garrett County, an LST anchored in the river. For 4 hours, the ship’s crew and embarked sailors fought off attempts to storm the vessel while waiting for reinforcements. The Riverrine forc’s ability to rapidly deploy large numbers of troops to threatened areas prevented what could have been catastrophic defeats.

General West Morland would later state that the mobile Riverine force saved the Delta during Tet. The assessment was accurate. Without the ability to move battalionsized forces along waterways, bypassing blocked roads and destroyed bridges, the Americans couldn’t have responded to simultaneous attacks across such a vast region.

The Brownwater Navy’s flexibility and firepower turned certain defeat into tactical victory in dozens of engagements. By mid 1968, the Mobile Riverine Force had expanded to two sections. Mobile Riverine Group Alpha and Mobile River Group Bravo. River Assault Squadrons 9, 11, 13, and 15.

At full strength, the force fielded over 100 combat craft and 15 support vessels. The third brigade of the 9inth Infantry Division rotated through riverine operations. The organizational structure had evolved into a welloiled machine where Army and Navy personnel understood each other’s capabilities and limitations. The typical combat operation now involved multiple layers of coordination that would have seemed impossible 2 years earlier.

Air Force tactical air control parties embedded with river assault squadrons could call in close air support within minutes. Army artillery forward observers aboard monitors directed fire from batteries positioned at Dong Tom or on floating barges. Navy Seawolves provided immediate helicopter gunship support. Their UH1B Hueies configured with rockets, miniguns, and machine guns specifically for riverine fire support.

SEAL teams used PBRs and swimmer delivery vehicles to conduct reconnaissance, ambushes, and direct action missions. Vietnamese regional forces and popular forces coordinated operations with American units, providing local knowledge and interpreters. The complexity of modern riverine warfare in Vietnam exceeded anything attempted in previous conflicts. Yet, it worked.

Statistics compiled by Admiral SA Schwarzber showed that in an average month of mobile riverine force operations, American forces conducted 300 SAM pan and junk inspections, detained 50 suspected Vietkong, killed or captured 15 confirmed enemy, destroyed 10 structures used for military purposes, and swept hundreds of miles of waterways for mines.

These numbers seem modest until you consider their cumulative effect. 12 months of operations meant 3600 inspections, 600 detentions, 180 confirmed enemy eliminated, 120 structures destroyed, thousands of miles secured. The slow strangulation of Vietkong logistics in the Delta changed the strategic equation. The human cost remained high. Between operation game warden and mobile riverine force operations, the brownwater navy suffered over 400 killed and more than a thousand wounded.

Small boats offered limited protection against heavy weapons. Mines could destroy vessels in seconds. Ambushes in narrow canals left no room for maneuver. Yet sailors and soldiers kept volunteering for riverine duty because the mission felt tangible. Unlike operations in the jungle where success was measured in ephemeral body counts, riverine forces could see the difference they made.

Villages once terrorized by Vietkong taxation now had protection. Waterways once impassible to civilian traffic operated normally. Food moved from the Delta to Saigon without interdiction. The sailors of the Brownwater Navy came from varied backgrounds, but shared common traits. Most were young, many barely out of their teens.

They learned to function on minimal sleep, conducting 12-hour patrols in heat and humidity that turned metal surfaces into griddles. They learned to identify the sound of different weapons by ear alone. Because knowing whether incoming fire came from an AK-47 or an RPG could mean the difference between effective response and death.

They learned that the Meong Delta had its own rhythms, that certain times and tides favored the enemy while others gave advantage to the Americans. They learned to read the behavior of civilians on sampans, recognizing fear, recognizing anger, recognizing the subtle signs that a boat carried more than rice and fishing nets.

Some became legends within the riverine community. Men like boats mate first class James Williams, who retired from the Navy in April 1967 as the most decorated enlisted sailor in history. Never made chief petty officer by examination, he was given the honorary title after his Medal of Honor ceremony. He would carry the decorations, the memories, and the nightmares for 32 more years before dying on October 13th, 1999 Navy’s birthday.

Today, an Arley Burke class destroyer bears his name, USS James E. Williams, DDG95. Men like the unknown sailors of river section 531 who survived the May 24th, 1967 ambush with 22 wounded but kept their boats moving, kept their guns firing, kept their discipline when everything said they should panic. Their names aren’t in Medal of Honor citations, but they’re inscribed on monuments at Navy bases where brownwater veterans gathered to remember the brothers who didn’t come home.

Men like the thousands of sailors who served in PBRs, ATC’s, monitors, and support craft, who did their jobs day after day in conditions that tested the limits of human endurance. Who learned that courage isn’t the absence of fear, but the discipline to function when fear is entirely rational. The Brownwater Navy’s success rested on elements that extended far beyond individual heroism or tactical innovation.

The industrial capacity that produced hundreds of specialized craft in months. The logistic system that kept operations supplied with fuel, ammunition, spare parts, and food. Despite operating hundreds of miles from major bases, the training pipeline that produced crews faster than casualties could deplete them.

The medical support that could treat casualties aboard ships, evacuate by helicopter, and deliver critically wounded men to field hospitals within golden hour time frames. The intelligence network that identified enemy concentrations and supply routes. The administrative structure that processed reports, adjusted tactics based on lessons learned, and maintained morale despite high casualty rates, and the knowledge that strategic victory remained elusive.

By 1969, as the Nixon administration began Vietnamization, the process of turning the war over to South Vietnamese forces, the Brownwater Navy began training their Vietnamese counterparts. Vietnamese sailors crewed PBRs under American supervision. Vietnamese officers assumed increasing responsibility for operations planning.

The transition happened faster than anyone desired because political considerations overrode military judgment about readiness. In December 1970, river patrol force units stood down. Their boats and equipment transferred to the Vietnamese Navy. The Mobile Riverine Force followed, the second brigade of the 9inth Infantry Division withdrawing while Vietnamese units attempted to maintain the operational tempo.

By March 1973, operations game warden, market time, and clear water officially ended. The last American brownwater navy units departed Vietnam. The historical record shows that Vietnamese forces couldn’t maintain the same level of operations. They lacked the logistics support, the spare parts, the ammunition expenditure rates, the helicopter support, and perhaps most critically, the training pipeline that had allowed American forces to sustain high casualty rates and continue functioning.

When North Vietnamese conventional forces invaded in 1975, sweeping aside South Vietnamese resistance, the Brownwater Navy that had once controlled the Delta existed primarily in memory. The boats were there. Many of the sailors who’d been trained by Americans were there. But the system that had made Riverine operations successful, the industrial and military infrastructure was gone.

The final assessment of brownwater Navy operations in Vietnam produces mixed conclusions. By every operational measure, the mission succeeded. Game warden and market time operations achieved 94% success rates in stopping maritime infiltration. By 1968, the flow of weapons and supplies along the coast came to a virtual standstill between 1965 in 1970.

Riverrine operations in the Delta disrupted Vietkong logistics, prevented major concentrations from operating freely, and allowed economic activity to continue in South Vietnam’s most productive region. The kill ratio of 40 to1 stands as one of the highest achieved by American forces in Vietnam. Two Medal of Honor recipients, hundreds of other decorations for valor, thousands of successful operations conducted under conditions that would have seemed impossible to conventional Navy planners. Yet strategically, the

Brownwater Navy couldn’t win the war because the war wasn’t winnable through riverine operations. Control of waterways didn’t address North Vietnamese infiltration from Cambodia and Laos. It didn’t solve the fundamental political problems within South Vietnam. It couldn’t prevent North Vietnamese conventional forces from eventually overwhelming the South.

In 1975, the Brownwater Navy gave the United States tactical dominance in a specific operational environment that proved insufficient for strategic victory. The lessons learned extended far beyond Vietnam. The Navy’s development of riverine warfare doctrine influenced later operations in Iraq and Afghanistan where inland waterways required patrol and control.

The SEAL teams that trace their Vietnam era riverine operations developed tactics still in use today. The concept of joint army Navy riverine operations established precedents for modern joint force operations. The medical evacuation procedures refined in the delta became standard across all services. The integration of air support with riverrain operations influence doctrinal development for close air support in urban and confined environments.

Perhaps most significantly, the Brownwater Navy demonstrated that the United States military could rapidly develop, deploy, and employ specialized forces for unconventional environments. Within two years, the Navy went from having essentially no riverine capability to fielding the most sophisticated brownwater force in history.

The boats were designed, built, tested, and deployed. The sailors were recruited, trained, and formed into effective units. The tactics were developed, refined through combat, and disseminated across the force. The logistics were established to support operations far from traditional Navy bases. That institutional flexibility, the ability to recognize a problem and create solutions from whole cloth remains one of the most impressive aspects of Brownwater Navy operations.

In 1985, at a reunion of Brownwater Navy veterans in San Diego, former adversaries from the Vietnamese Navy attended as guests. Men who’d been enemies decades earlier shared stories, compared experiences, and discovered that the terror, the confusion, and the occasional absurdity of riverine combat transcended national boundaries.

A former Vietkong naval officer who’d survived numerous engagements with PBRs admitted something that surprised the Americans present. He’d been terrified of the PBRs, the speed, the firepower, the apparent recklessness with which American crews attacked, even when outnumbered. His unit had learned to avoid direct confrontation with PBRs whenever possible, to rely on mines and ambushes from concealed positions because fighting American rivercraft in open water meant certain death.

The Americans in turn admitted their fear. Every patrol could be an ambush. Every bend could hide a mine. The sampan approaching peacefully might contain a family going to market or might explode in a suicide attack. The stress of maintaining alertness for 12-hour patrols day after day, month after month, had broken men who’d seemed unbreakable during training.

The mutual respect was genuine. Both sides had fought in conditions that tested the limits of human capability. Both had demonstrated courage and skill. Both had paid terrible prices for their service. In 1990, Vietnam opened to Western tourism. Some brownwater Navy veterans returned to the Delta, traveling on hired boats through rivers they’d last seen from PBR gunnels.

The landscape had changed. Villages rebuilt or relocated. Vegetation reclaimed areas that had been napalmed bare during the war. The scars of conflict had healed or been hidden by decades of growth. But the rivers remained. The Mikong still split into its maze of channels. The muddy brown water still carried traffic, now peaceful sam pans and motorized vessels rather than military craft.

The currents still ran fierce during monsoons. The heat and humidity were unchanged. Veterans stood on banks where they’d fought desperate battles, trying to reconcile their memories of chaos and fire with the quiet pastoral scenes before them. Some found closure. Some found that the ghosts couldn’t be exercised by visiting battlefields long cold.

Most found that their service, while ultimately unsuccessful at its strategic goal, had mattered. They’d done what was asked of them, often heroically, always professionally, under conditions that most Americans couldn’t imagine. The Brownwater Navy story occupies a unique place in American military history. It was the Navy fighting on rivers and canals, an environment the service had largely abandoned after the Civil War.

It was high casualty operations that somehow maintained volunteer rates because sailors believed in the mission. It was tactical success that couldn’t produce strategic victory. It was innovative thinking that developed an entire warfare specialty from scratch in months. It was young men, often still teenagers, operating sophisticated weapon systems in three-dimensional environments where decisions had to be made in seconds, and mistakes meant death.

Today, models of PBRs, ATC’s, monitors, and ASPBS sit in the National Museum of the United States Navy in Washington, DC. PCF1, a patrol craft fast from market time operations, is displayed outside the Cold War Gallery. The exhibits explain the technical specifications and operational history. They show photographs of sailors at their weapons, of boats under fire, of the mobile riverine base anchored in the Meong.

But the real story isn’t fully captured by displays and plaques. It’s in the memories of veterans who still wake up hearing the sound of twin 50 caliber machine guns, who still flinch at sudden loud noises, who still carry the names of men who didn’t come home. It’s in the Medal of Honor citations that use words like conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity, but can’t fully describe what it meant to charge into overwhelming enemy fire because there were no exit ramps.

It’s in the operational reports that list vessels destroyed, enemy killed, miles patrolled, but can’t quantify the fear, the exhaustion, the dark humor that let men function in impossible situations. It’s in the transformation that occurred between December 1965 when skeptics questioned whether the Navy could fight on rivers and March 1973 when American brownwater forces departed Vietnam having established complete tactical dominance over thousands of square miles of waterways.

In Vietnamese, the Mikong is Song Ku Long, the river of nine dragons. American sailors learned to navigate those dragons domains. To fight and win in waters that had belonged to the enemy, to control liquid highways through audacity, firepower, and courage. They laughed at the riverboats in Vietnam. the traditional Navy men who couldn’t imagine how small craft would matter until the Brownwater Navy cut off the Vietkong supply lines, strangled enemy logistics, and proved that American ingenuity and industrial might could

create victory even in the most hostile environments. The transformation from mockery to respect took 18 months. Within that time, fiberglass boats became synonyms for terror among Vietkong fighters. The sound of Jacuzzi water jet pumps approaching at high speed became a warning to scatter. The sight of American flags on the water meant danger rather than opportunity.

James Williams and his crew aboard PBR 105 demonstrated on October 31st, 1966. What the Brownwater Navy would prove over thousands of engagements across seven years. That courage, training, and superior firepower could overcome overwhelming numerical odds. That American sailors could adapt to any environment and develop the tactics needed to win.

that even in a war where strategic victory proved elusive, tactical excellence still mattered. The Brownwater Navy fought and won its war. The Vietkong never regained control of the Delta’s waterways while American forces operated there. The supply routes stayed cut. The rivers stayed open. The mission succeeded.

That the broader war ended differently doesn’t diminish the achievement. They laughed at the riverboats until the day they met them in battle. Then the laughter died, replaced by fear and respect for men who’d mastered the art of violence on the water. The Meong runs brown with silt, staining everything it touches. For seven years, it also ran red with the blood of those who fought to control it.

American sailors wrote their names on those waters in combat reports and Medal of Honor citations, in tactical innovations and operational successes. The Brownwater Navy’s legacy endures not in territory controlled or strategic objectives achieved, but in lessons learned about adaptability, courage, and the lengths to which free men will go when asked to fight on unfamiliar ground against determined enemies.

Those lessons remain valid today. The enemies change, the theaters change, the specific tactics and equipment evolve, but the fundamental truth demonstrated by the Brownwater Navy remains constant. When Americans are given a mission, adequate resources, proper training, and strong leadership, they will find a way to succeed regardless of the environment or the odds.

They laughed at the riverboats until 850 caliber machine guns mounted on fiberglass hulls racing through narrow canals at 40 knots taught them that American ingenuity makes weapons from anything, even from pleasure boats and jacuzzi pumps. The thunder rolled across the delta for seven years. And when it finally fell silent, the rivers belonged to those who’d had the courage to fight for them.