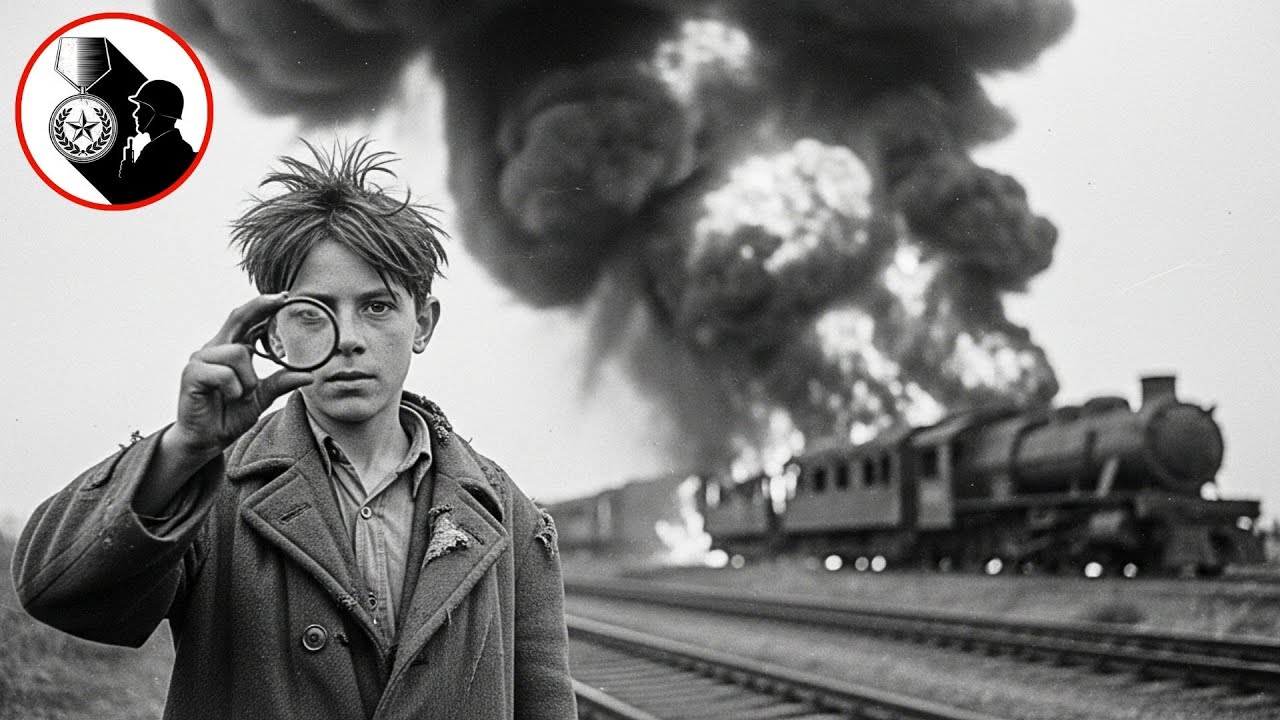

T 12-year-old boy crouches behind a snow-covered embankment in occupied Poland, his breath forming clouds in the freezing air of 1943. In his trembling hand, he holds nothing but a broken lens from his grandmother’s reading glasses. Below him, a Nazi supply train rumbles along the tracks, carrying ammunition, fuel, and weapons destined for the Eastern Front.

The boy waits. He angles the lens toward the winter sun. And then impossibly the train explodes. No bombs, no rifles, no Allied commandos. Just a child, a piece of glass, and the physics that the Third Reich never saw coming. This is not fiction. This is not a movie. This is the true story of how one of the youngest resistance fighters in World War II turned sunlight into a weapon and struck terror into the heart of the Nazi war machine.

By the end of this video, you will discover how a boy with nothing became one of the most effective saboturs the Nazis never caught, and why his story has been buried in the footnotes of history for over 80 years. Before we understand how a child could weaponize something as simple as sunlight, we need to go back to the world he lived in.

Poland in 1941 was a nation suffocating under the iron grip of Nazi occupation. The German war machine had crushed Polish defenses in just 36 days during the invasion of 1939. And by the time our story begins, the country had become a vast prison camp. Cities were renamed. Polish was banned in schools.

Families disappeared in the middle of the night. The Nazis didn’t just occupy Poland. They tried to erase it. In the countryside, far from the watchful eyes of the Gestapo headquarters in Warsaw, small villages clung to survival. These were farming communities where everyone knew everyone, where life had remained unchanged for generations.

But the war changed everything. Young men were taken for forced labor in German factories. Food was rationed to starvation levels. And the trains, those endless Nazi trains, rolled through day and night carrying the machinery of genocide and conquest. In one of these villages, a boy named Joseph lived with his grandmother in a small wooden cottage at the edge of a forest.

His parents had been taken 2 years earlier, dragged from their home by SS officers, and never seen again. Joseph was small for his age, thin from malnutrition, with dark eyes that had seen too much too soon. His grandmother, a stern woman in her 70s, was all he had left. She taught him to read using her old prayer book and her reading glasses, thick lenses that magnified the tiny print.

Life was quiet. Life was careful. You survived by being invisible by keeping your head down by never attracting attention. But Ysef had a problem. He couldn’t stay invisible. Every day he watched the trains pass through the valley below their cottage. He counted them, memorized their schedules, and he burned with a hatred that no 12-year-old should have to carry.

The trains haunted him. They were the veins of the Nazi occupation, pumping resources from Poland to feed the German war effort. Joseph knew that somewhere on those trains were the supplies that kept the camps running, the ammunition that killed resistance fighters, the fuel that powered the tanks crushing Soviet villages.

He also knew that destroying a train was impossible. The tracks were guarded. Patrols swept the countryside. Saboturs were hanged in public squares as warnings. The Polish resistance, the Army of Cryoa, operated in the shadows, and they didn’t recruit children. Joseph was alone. But being alone didn’t mean being powerless.

It just meant he had to think differently. One afternoon in late summer of 1942, Yoseph sat on the hillside watching the trains. The sun was brutal that day, beating down on the metal tracks until they shimmerred with heat. He had brought his grandmother’s reading glasses to pass the time, using the thick lenses to focus sunlight into tiny points that could burn holes in leaves.

It was a game, a distraction. But as he watched a particularly long supply train crawl around the bend, something clicked in his mind. Fire. The trains carried fuel. The tanker cars were painted with warning symbols, and glass, when angled correctly, could concentrate sunlight into a beam hot enough to ignite almost anything. The idea was insane.

It was impossible. It was brilliant. Yoseph pocketed the glasses and ran home, his heart pounding with a plan that would either make him a hero or get him killed. For weeks, he studied. He tested angles. He experimented with distance and timing. He learned that the lens needed to be held at exactly the right position to create a focal point small enough and hot enough to ignite fuel vapors.

He learned that he had only seconds when the train slowed on the uphill curve. He learned that if he failed, if he was spotted, his grandmother would pay the price alongside him. But Joseph also learned something else. He learned that the Nazis, for all their power and brutality, had a weakness. They never imagined that a child with a piece of glass could be a threat.

They never saw him coming, and that invisibility, that underestimation would become his greatest weapon. The first attempt came on a cold morning in October of 1942. Ysef had chosen his position carefully, a rocky outcrop hidden by dense brush that overlooked the steepest section of track where trains slowed to a crawl.

He arrived before dawn, his grandmother’s lens wrapped in cloth and tucked into his coat. She thought he was foraging for mushrooms in the forest, a dangerous lie that made his stomach twist with guilt. But this was bigger than one boy, bigger than one family. This was about making the Nazis bleed, even if just a little.

He waited for 3 hours, shivering in the morning frost, until he heard the distant rumble of an approaching train. His hands shook as he unwrapped the lens. This was it, the moment that would either prove his theory or expose him as a foolish child playing with forces beyond his control. The train came into view slowly, a massive serpent of steel cars marked with German military insignia.

Ysef counted the cars as they passed, infantry transport, ammunition, medical supplies, and then midway through the convoy, he saw it. A fuel tanker, the kind that supplied Panza divisions and Luftvafa airfields. The yellow diamond warning symbol was clearly visible, even from his distance. The train began its climb up the grade, wheels screeching against the rails as it slowed to barely more than walking speed. Yazf positioned himself.

He angled the lens toward the sun which had finally broken through the morning clouds. A bright point of light appeared on the ground in front of him. He adjusted. The point sharpened. His heart hammered so loudly he was certain someone would hear it. Then he aimed the concentrated beam at the seam where the tanker car’s fuel cap met the metal housing, a spot he had identified during his weeks of observation as the most likely point of vapor escape.

Nothing happened. 10 seconds passed. 20. The train continued its slow crawl up the grade. Joseph’s arm began to ache from holding the lens perfectly still. Sweat dripped into his eyes despite the cold. Had he miscalculated? Was the fuel too well sealed? Was this entire plan the fantasy of a desperate child? And then, just as the tanker began to move out of range, he saw it.

A thin wisp of smoke, then a flicker of orange, then a small flame that seemed to dance along the metal seam. For one frozen moment, Ysef thought it would simply burn out. But fuel vapor is patient. It waits for its moment. And when that moment comes, it doesn’t ask permission. The explosion tore through the morning silence like the fist of an angry god.

The tanker car erupted in a massive fireball that lifted the entire vehicle off its wheels and slammed it sideways into the car behind it. Secondary explosions followed as the fire spread. Black smoke poured into the sky. The train lurched to a halt, its brakes screaming. Yosef didn’t wait to see more.

He grabbed the lens, shoved it into his coat, and ran. His legs pumped through the forest undergrowth, branches tearing at his face and clothes. Behind him, he could hear shouting in German the sharp commands of officers organizing a search. His lungs burned, his vision blurred. But he didn’t stop running until he burst through the door of his grandmother’s cottage, chest heaving, face white with terror and exhilaration.

His grandmother looked up from her sewing, her weathered face unreadable. She saw the soot on his hands, the wild look in his eyes, the way he clutched her reading glasses like a sacred relic. She said nothing. She simply stood, walked to the window, and looked toward the column of black smoke rising in the distance.

Then she turned back to her grandson, placed one wrinkled hand on his shoulder, and squeezed once. It was the only acknowledgement he would ever receive. It was enough. Joseph had struck his first blow against the Third Reich, and he was just getting started. The Nazi response was swift and brutal. Within hours of the explosion, SS units swept through the surrounding villages like a plague of locusts.

They went house to house, interrogating families, searching barns and cellers, looking for any sign of resistance activity. Three men from a neighboring village were arrested on suspicion of sabotage and hanged from lampposts in the town square as a warning. Their bodies were left there for 5 days, swaying in the autumn wind, a grotesque reminder of what happened to those who defied the Reich.

The Germans assumed this was the work of the Polish resistance, the Army Cra, and they responded with the only language they knew, overwhelming force and collective punishment. But they were hunting ghosts. They interrogated adults, tortured suspected partisans, and increased patrols along the railway line.

Not once did they consider that the sabotur might be a malnourished 12-year-old boy with a piece of glass. Yazf watched the hangings from a distance, hidden among the crowd of terrified villagers forced to witness the executions. He felt the weight of those deaths like stones in his stomach. Three innocent men died because of what he had done.

But he also understood something crucial in that moment. The Nazis were afraid. That explosion had disrupted their supply line, caused chaos, and forced them to divert resources to security. One boy with one lens had made the mighty Third Reich flinch, and if he could do it once, he could do it again. For the next 6 months, Ysef became a ghost on the hillsides.

He developed a system, a careful methodology born from equal parts desperation and genius. He never struck from the same position twice. He studied the patrol schedules and learned when the guards changed shifts, when their attention was weakest. He memorized the train timets, noting which convoys carried the most valuable cargo, and which routes were least guarded.

He became an expert in the physics of focused sunlight, understanding how weather conditions, time of day, and angle of incidence affected the intensity of the beam. On cloudy days, he didn’t even attempt to strike. On clear days with strong sun, he could ignite fuel vapors in under 30 seconds. He learned to read the trains themselves, identifying which tanker cars were full by how they sat on the tracks, which ammunition cars were most volatile, which supply trains were headed to the eastern front versus the western occupied territories. His

grandmother never asked questions, but she began leaving him extra food wrapped in cloth, and she stopped wondering aloud where her reading glasses had gone. By the spring of 1943, Ysef had successfully sabotaged seven trains. Not all attempts resulted in catastrophic explosions like the first one.

Sometimes he only managed to start small fires that forced the trains to stop for emergency inspections, causing delays that rippled through the German supply chain. Sometimes the fire spread slowly enough that crew members extinguished it before major damage occurred. But twice more he achieved direct hits on fuel tankers that resulted in massive explosions visible for kilometers.

Each success made him bolder. Each success also increased the danger. The Germans knew someone was targeting their supply lines in this specific region. They tripled patrols. They installed machine gun nests overlooking key sections of track. They began running decoy trains to draw out saboturs. The area became one of the most heavily guarded sections of railway in occupied Poland.

And still the attacks continued. Still trains burned. The Germans began to whisper among themselves about ghosts, about cursed sections of track, about divine punishment for their sins. They never suspected the truth because the truth was too absurd to consider. But Yosef was pushing his luck and he knew it. Each mission brought him closer to discovery.

Each time he positioned himself on those hillsides, he was gambling with not just his own life, but his grandmother’s as well. The margins were getting thinner, guards were more alert, patrols covered more ground, and winter was ending, which meant longer days with more hours of sunlight, but also less cover in the forests as leaves had not yet returned to the trees.

He needed to be smarter. He needed to evolve his tactics. So he began scouting new locations further from his village, places where a young boy traveling alone might seem less suspicious. He started carrying the lens in different ways, sometimes hidden in a hollowedout book, sometimes sewn into the lining of his coat.

He created false reasons for being in the countryside, foraging, checking rabbit snares, delivering messages between farms. He became an actor playing the role of an innocent child. and he played it so convincingly that even when German soldiers stopped him for questioning, they saw nothing but a scared, hungry boy trying to survive. The turning point came in May of 1943.

Yosef had positioned himself near a railway bridge, a new location he had scouted carefully. The train approaching was different from the others. It was heavily guarded with armed soldiers visible on flatbed cars at the front and rear. The tanker cars in the middle convoy were marked with special insignia he had never seen before.

Later he would learn this was a high priority fuel shipment destined for a major German offensive on the eastern front. But in that moment all he knew was that this train mattered. He could feel it. The guards were tense, alert, scanning the tree lines with binoculars. Joseph waited until the train began crossing the bridge.

a moment when the guard’s attention was focused on the structure itself, watching for explosives or structural sabotage. That’s when he made his move. He angled the lens, found his focal point, and held steady as the concentrated beam of sunlight found its target on the lead tanker car. What happened next would change everything. The explosion was unlike anything Yosef had ever created before.

The lead tanker didn’t just catch fire. It detonated with such force that the shock wave knocked him backward into the dirt, even from his distant position on the hillside. The fireball rose 30 m into the air, a churning column of orange and black that seemed to tear a hole in the sky itself. But this time, the fire didn’t stop with one car.

The tankers were positioned too closely together, and the heat from the first explosion ignited the second, then the third, creating a chain reaction of devastation that turned the entire middle section of the train into an inferno. The bridge itself began to groan under the stress, metal warping from the intense heat.

Yosef watched in frozen horror as the structure buckled, then collapsed, sending burning wreckage plummeting into the ravine below. He had not just destroyed a train. He had destroyed a critical piece of Nazi infrastructure. And the Reich would not forgive this. Within 24 hours, the entire region was locked down under martial law.

Every village within 20 km of the destroyed bridge was placed under immediate curfew. German troops conducted door-to-door searches with a thoroughess that bordered on madness. They interrogated everyone from elderly farmers to children barely old enough to walk. They brought in Gestapo interrogators from Warsaw, men whose reputation for extracting confessions through torture was legendary.

They offered massive rewards for information, enough money to feed a family for a year. They made it clear that the entire population would suffer until the sabotur was found. Public executions became daily events. Hostages were taken from each village and held in makeshift detention centers. The pressure was unbearable, suffocating, designed to turn neighbor against neighbor, to make silence more painful than betrayal.

And through it all, Ysef had to remain perfectly calm, perfectly normal, perfectly invisible. The hardest part was not the fear of being caught. It was the guilt. Every morning he woke to news of more arrests, more executions, more families torn apart because of what he had done. He saw the faces of the condemned ordinary people who had nothing to do with the resistance but were being murdered as collective punishment.

One of them was the village baker, a kind man who had sometimes slipped Yoseph extra bread when he thought no one was looking. Another was a young mother who had three children under the age of six. They died because Yosef had been too successful because his attack had hurt the Germans badly enough that they responded with genocidal fury. He stopped eating.

He barely slept. His grandmother watched him waste away with silent understanding. And one night she finally spoke. She told him about his grandfather who had fought in the great war and came home broken by what he had seen. She told him that war forces impossible choices on good people, that every act of resistance carries a cost, and that the blood of innocence stains the hands of tyrants, not those who fight them.

Her words didn’t erase the guilt, but they gave him permission to carry it without being crushed by it. For 3 weeks, Ysef did nothing. He couldn’t risk another attack while the German presence was so overwhelming. He went through the motions of daily life, helped his grandmother with chores, attended the mandatory Nazi propaganda sessions in the village square, and played the role of a traumatized child living under occupation, which in truth he was, but he also watched.

He observed how the Germans operated, how they thought, how they responded to threats. He noticed that their security measures were reactive rather than proactive. They fortified areas after attacks, but left other sections vulnerable. They focused their attention on adult men and known resistance sympathizers, but ignored children and elderly women.

They relied on informants and torture, but seemed incapable of understanding that resistance could come from the most unlikely sources. And slowly, carefully, Ysef began to plan his next move. Because stopping now would mean those deaths were for nothing. Stopping now would mean the Nazis had won. The opportunity came in early June when the German command, confident that their show of force had crushed any resistance in the region, began to reduce patrols and redirect troops to other areas.

The bridge was being rebuilt, but railway traffic had been rerouted through a secondary line that passed through even more remote countryside. This new route was longer, slower, and according to the whispered conversations Yosef overheard when Germans spoke too freely around children they didn’t consider threats.

It was carrying some of the most critical supply shipments to the Eastern Front. The Nazis were desperate to make up for lost time, to restore the flow of materials that Yosef’s attack had disrupted. They were rushing and when people rush they make mistakes. Joseph understood this instinctively. He had learned patience from months of careful observation.

But he had also learned that windows of opportunity close quickly. This was his chance to strike again to prove that one boy with determination could not be stopped by fear or force. He retrieved the lens from its hiding place beneath a loose floorboard in his grandmother’s cottage. He studied the new train route and he prepared to become a ghost once more.

The new railway route passed through a section of countryside that the locals called the Valley of Wolves, a name earned from the packs that had roamed there before the war. It was isolated, heavily forested, and featured a long uphill grade where trains slowed to a crawl under the strain of pulling heavy cargo. For Yosef, it was perfect.

The forest provided cover. The terrain offered multiple escape routes, and the distance from any village meant fewer witnesses and less immediate German response time. He spent a week scouting the area, memorizing every tree, every rock formation, every depression in the ground that could serve as a hiding spot.

He timed the patrols and discovered they were sparse here. Just a single motorcycle unit that passed through twice daily at predictable intervals. The Germans had made a calculation. They believed that their brutal crackdown had worked, that fear had pacified the population, that no one would dare strike again. They were about to learn how wrong they were.

Joseph chose his position on a rocky ledge halfway up the valley’s eastern slope, concealed by thick pine branches, and positioned to catch the full strength of the afternoon sun. He arrived 3 hours before the scheduled train, giving himself time to settle in, to control his breathing, to prepare mentally for what was coming.

This time felt different. The first attacks had been fueled by rage and desperation, by a need to hurt the enemy however he could. But now, after weeks of witnessing the cost of resistance, after seeing the faces of those who had died because of his actions, he understood the weight of what he was doing.

He was not playing games. He was fighting a war and in war people died. Innocent people, guilty people, everyone. The only choice was whether their deaths meant something or nothing. Yosef had decided his would mean something. He would make the Nazis pay for every mile of Polish soil they occupied, for every family they destroyed, for every life they stole, even if it cost him everything.

The train appeared exactly on schedule, a long convoy of cargo cars marked with vermarked insignia. Joseph counted 23 cars in total, a massive shipment that likely represented weeks of accumulated supplies being pushed toward the eastern front where German forces were locked in desperate combat with Soviet armies.

He watched through gaps in the branches as the locomotive began its climb. Black smoke pouring from its stack as the engine strained against the grade. The cars rocked and swayed on the tracks, their coupling chains clanking rhythmically. And then he saw them. Four tanker cars positioned near the middle of the convoy, each one marked with the distinctive yellow diamond warning symbol that indicated high-grade fuel.

His heart rate quickened, but his hands remained steady. He had done this enough times now that the physical motions were automatic, muscle memory refined through repetition and necessity. He unwrapped the lens from its protective cloth. He checked the sun’s position. He calculated angles and distances with the unconscious precision of someone who had turned this act into an art form.

The train entered the steepest section of the climb, its speed dropping to barely faster than a walking pace. The wheels screeched against the rails, metal grinding against metal in a sound that made Joseph’s teeth ache. This was the moment. He raised the lens, angled it toward the sun and watched as a brilliant point of light appeared on the ground before him.

He adjusted the angle fractionally, and the point sharpened into a focused beam of concentrated solar energy. Then, with practiced precision, he directed that beam toward the fuel cap of the second tanker car. He had learned through experience that the second car was optimal. If he targeted the first, the explosion might derail the train in a way that protected the other tankers.

If he targeted one too far back, the crew might have time to uncouple cars and minimize damage. The second car was the sweet spot, the point where maximum destruction met maximum tactical advantage. He held the beam steady, counting silently in his head. 1 2 3 The metal began to discolor from the heat. 4 5 6 A thin wisp of smoke appeared.

7 8 His arm trembled slightly from holding the position. 9 10 A small flame flickered to life and then the world exploded. This time Ysef was ready for the blast. He had positioned himself behind a large boulder that absorbed most of the shock wave, though he still felt the wave of heat wash over him like opening an oven door.

The tanker erupted in a fireball that engulfed three cars immediately, and within seconds, the other fuel tankers joined the conflration. But something else happened that Joseph had not anticipated. The intense heat caused one of the cargo cars to explode with a different sound. A sharper crack followed by multiple secondary blasts. Ammunition.

He had hit an ammunition transport without realizing it. The combination of fuel fire and exploding ordinance turned the train into a vision of hell. Cars were lifted off the tracks and flung sideways. The locomotive trying desperately to pull away from the inferno lost traction and began sliding backward down the grade.

Soldiers who had been riding in guard cars jumped clear, rolling down embankments to escape the flames. The entire valley filled with smoke so thick that Joseph could barely see 50 m in any direction. And in that smoke, he disappeared like the ghost the Germans believed him to be. The aftermath of the Valley of Wolves attack sent shock waves far beyond the immediate destruction.

This was no longer a local nuisance that could be contained with a few public executions and increased patrols. This was a strategic problem that demanded attention from the highest levels of German command in occupied Poland. The destroyed train had been carrying critical fuel reserves and ammunition stockpiles intended for Army Group Center, which was engaged in fierce defensive operations against a massive Soviet offensive.

The loss represented not just material damage but a significant disruption to carefully planned logistics. Vermarked officers began asking uncomfortable questions. How could resistance fighters operate so effectively in an area that was supposedly pacified? How were saboturs evading detection despite massive security measures? And most troubling of all, why did the attack seem to happen with such precision, always targeting the most valuable cargo at the most vulnerable moments? The answers they came up with were all wrong, but their

response was predictably brutal. The Gustapo deployed a special investigative unit to the region, men who specialized in counterinsurgency operations and had extensive experience fighting partisans in other occupied territories. They brought with them a level of sophistication that the local SS units lacked.

They analyzed attack patterns, studied blast trajectories, interviewed surviving train crews, and examined the wreckage for forensic evidence. They operated under the assumption that they were dealing with a highly trained sabotage cell, possibly working with explosive experts from the Polish underground or even Allied special forces.

They built elaborate theories about resistance networks, supply chains for explosives, and coordination with Soviet intelligence. They constructed a profile of their enemy, militarytrained, technically skilled, part of a larger organization operating with external support. Every element of their profile was completely incorrect.

But their methodology was sound enough that they came dangerously close to the truth in ways they never recognized. They noted, for instance, that attacks only occurred on clear, sunny days, but they attributed this to visibility concerns for spotters rather than understanding the actual mechanism. They were looking for shadows and found none because they refused to consider that the light itself might be the weapon.

Yosef watched this investigation unfold from his position of perfect invisibility. He saw the Gestapo officers in their long leather coats, moving through villages, setting up command posts, spreading maps across tables in requisitioned houses. He saw them interview his neighbors, question children about suspicious activities, offer rewards that grew larger each week.

He even saw them inspect the hillside where he had launched the Valley of Wolves attack, walking right past his hiding spot without seeing the small indentations where his knees had pressed into the dirt. They were looking for evidence of explosives, for detonation triggers, for the infrastructure of conventional sabotage. They never looked at the sky.

They never considered that a weapon could be as simple as focused sunlight and patience. And that blindness, that failure of imagination, was what kept Yosef alive. He was hidden not by elaborate cover stories or resistance networks, but by the simple fact that what he was doing seemed impossible to trained military minds.

Adults expected adult solutions to problems. They could not conceive that a child with no training, no equipment, and no support could wage effective war against the most powerful military machine in Europe. But the increased German presence changed everything about how Yosef had to operate. The window for attacks narrowed dramatically.

Patrols became unpredictable with random timing designed to catch saboturs off guard. The Germans began varying train schedules, running convoys at different times each day to prevent pattern recognition. They installed additional guards on high-value transports and positioned observers along the tracks with orders to watch for any suspicious activity.

Most significantly, they started clearing vegetation from areas near the railway, cutting down trees and brush that could provide cover for saboturs. The tactical environment that had allowed Yosef to operate was being systematically dismantled. He realized that if he wanted to continue his private war, he would need to adapt once again. The easy targets were gone.

The simple approaches were too dangerous. He needed to be smarter, more patient, and more willing to take risks that even he recognized as potentially suicidal. But he also understood something the Germans did not. Their increased security measures were evidence that his attacks were working, that he was causing real damage, that somewhere in Berlin, officers were being yelled at because supplies were not reaching the front lines.

One boy with a lens was forcing the Third Reich to divert resources, attention, and manpower to a backwater region of Poland that should have been completely pacified. That knowledge was fuel for his determination. Summer arrived in full force, bringing with it long days of intense sunlight that should have been perfect for Yosef’s purposes.

But the German countermeasures made each potential attack exponentially more dangerous. He spent weeks simply observing, learning the new patrol patterns. identifying weaknesses in the enhanced security. He discovered that the Germans had a blind spot in their thinking. They focused heavily on protecting the trains themselves and the immediate areas around the tracks, but they paid less attention to elevated positions farther from the railway.

They assumed that saboturs needed to be close to their targets. That distance reduced effectiveness. They were thinking about bombs and guns, weapons with limited range and requiring proximity. They were not thinking about light, which could travel hundreds of meters without losing its concentrated power.

Yosef began scouting positions that were farther away than he had ever attempted before, places where he could operate with greater safety margins, but would need perfect conditions and flawless execution to succeed. He was evolving from a guerilla fighter into something more sophisticated. He was becoming a sniper, except his weapon was the sun, and his ammunition was infinite.

The attack that would cement Yosef’s legacy came on a scorching afternoon in late July of 1943. He had identified a position nearly 400 m from the tracks, an unprecedented distance that would have been impossible with conventional sabotage methods. The location was a natural rock formation on a hilltop that provided an unobstructed view of a long straightaway where trains picked up speed after navigating a series of curves.

The Germans had cleared vegetation near the tracks, but had not extended their efforts this far up the hillside. Assuming that such distance rendered the position useless for sabotage, they were correct for every weapon except the one Joseph wielded. He had tested the angle repeatedly over the previous week, using scraps of dry wood to prove that he could still achieve ignition at this extreme range.

The focal point was smaller, requiring absolute precision, but it was possible, and possibility was all he needed. The train he targeted that day was the most heavily guarded convoy he had ever attempted. Intelligence had somehow leaked through the village whisper network that this particular transport carried high-grade aviation fuel destined for Luftvafer bases supporting operations on the Eastern Front.

The Germans knew this shipment was valuable and had taken extraordinary precautions. Armed guards were positioned on every third car. A spotter plane flew overhead reconnaissance patterns. Motorcycle patrol swept the area 2 hours before the train’s scheduled passage, but all their security measures assumed a threat that would come from ground level, from close range, from the shadows.

They never looked up toward the distant hilltop where a skinny 12-year-old boy lay perfectly still among the rocks. His grandmother’s reading lens catching fragments of sunlight as he waited with the patience of a predator. Joseph had learned that the key to survival was not just striking hard, but knowing when to be absolutely motionless, when to let the enemy’s own vigilance exhaust itself, while he remained a statue carved from stone and determination.

The train appeared as a dark line against the summer haze, its approach announced by the distant rumble that Ysef had learned to recognize by vibration before sound. He watched it navigate the curves, saw the guards scanning the cleared areas beside the tracks, observed their body language shift from high alert to relaxed routine as they passed through the danger zones without incident.

This was the psychology he exploited. Security forces could not maintain peak alertness indefinitely. There was always a moment when caution gave way to confidence. When the absence of threat became its own kind of camouflage. As the train entered the straightaway and began to accelerate, the guards visibly relaxed. Some lit cigarettes, others turned their attention inward toward conversations with fellow soldiers.

They had passed through the vulnerable section. They were safe now. Or so they believed. Joseph slowly raised the lens, his movement so gradual that even a bird watching would not have registered the motion as threatening. He found the sun positioned at its peak intensity in the cloudless sky, and he began the delicate work of murder through physics.

At 400 m, the margin for error was non-existent. The slightest tremor in his hand would scatter the focal point across meters of empty air. The wind, which had been negligible all morning, could shift the beam away from its target in an instant. Even his own breathing could disrupt the precise angle required for ignition.

So Ysef did what he had trained himself to do over months of practice. He became still, not just physically motionless, but mentally calm, entering a state of focus so complete that the world narrowed to three elements, the sun, the lens, and the target. The rest of reality ceased to exist.

He could not hear the birds in the trees behind him. He could not feel the heat of the rocks beneath his body. He could not think about his grandmother waiting at home, or the men who would die if he succeeded, or the torture that awaited him if he failed. There was only the beam of light, thin as a needle, reaching across 400 m of summer air to touch the fuel cap of the third tanker car. He held it there, 30 seconds, 45.

His entire body screamed with the effort of remaining perfectly still, one minute, and then, impossibly far away, he saw the first wisp of smoke rise from the metal. What happened next occurred in dreamlike slow motion, despite the actual violence of the event. The smoke thickened.

A flame appeared, small at first, almost delicate. Then the fuel vapors inside the tanker reached critical temperature and ignited with a blast that tore the car apart from the inside out. But this time, because the train was moving at speed rather than crawling uphill, the physics of the destruction were different. The explosion created a chain reaction, not through heat, but through kinetic force.

The destroyed tanker car derailed at high velocity, its momentum causing it to slam into the car ahead, while the car behind crashed into it from the rear. The entire middle section of the train accordioned, cars piling into each other in a catastrophic chain collision. Then the other fuel tankers, ruptured by the impact, added their own contributions to the inferno.

Within seconds, a train that had been moving at full speed became a stationary wall of flame stretching across 200 m of track. The spotter plane circling overhead radioed an emergency report that was received with disbelief at German headquarters. Impossible, they said. No explosion was reported. No saboturs were spotted.

The train simply erupted into flames in the middle of an open straightaway under perfect visibility conditions. But impossible or not, 30,000 L of aviation fuel were burning uselessly in a Polish field, and the Luftvafa squadrons, depending on that fuel, would remain grounded while Soviet aircraft controlled the skies. Yuzf watched the smoke rise, then carefully wrapped his lens, and began the long walk home.

He had just changed the course of battles he would never see, saved lives he would never know, and proved that even the smallest resistance could strike at the heart of tyranny. The German response to the straightaway attack transcended brutality and entered the realm of desperation. Within 48 hours, the entire region was placed under total lockdown.

No one could enter or leave without special permits issued personally by the regional Gestapo commander. A reward of 50,000 Reichs marks was offered for information leading to the sabotur’s capture. An astronomical sum that represented more money than most Polish families would see in a lifetime. The Gestapo brought in specialist interrogators from Berlin.

Men whose techniques were so extreme that even hardened SS officers found them disturbing. Every male over the age of 14 in a 20 km radius was detained for questioning. Torture became routine. Three men died during interrogations without revealing anything because they had nothing to reveal.

The Germans were chasing a phantom and their frustration manifested as genocidal rage against a population that genuinely had no information to provide. The irony was suffocating. The resistance fighters they were torturing would have happily claimed credit for the attacks if they had been responsible. But they were as mystified as the Germans about how these strikes were being executed.

Joseph watched his village transform into an openair prison. Checkpoints appeared at every crossroads. Patrols moved through streets at all hours. Loudspeakers mounted on trucks blared threats and propaganda promising collective punishment if the sabotur was not surrendered. His grandmother’s cottage was searched twice.

Once by local SS troops who barely glanced around before leaving, and once by Gestapo investigators who spent three hours examining every floorboard and piece of furniture. Yosef was home during the second search, sitting quietly at the kitchen table, while men in leather coats tore apart the only home he had left.

They questioned him perpunctually, asking if he had seen any suspicious activity, any strangers in the woods, any unusual behavior from neighbors. He answered in the frightened halting voice of a traumatized child which required no acting because that was exactly what he was. They looked at his thin arms, his malnourished frame, his two large eyes in a two small face, and dismissed him as irrelevant.

One investigator even patted his head absently while instructing his grandmother to keep the boy away from the woods, as if Yosef were a puppy that might wander into danger. They never searched him personally. They never asked about the reading glasses that sat in plain view on the kitchen shelf, one lens conspicuously missing.

They were looking for radio equipment, weapons, explosives, maps. They were not looking for an old woman’s broken spectacles. But the pressure was becoming unsustainable. Yosef could see it in his grandmother’s face the way she aged years in a matter of weeks. She never asked him to stop, never spoke directly about what he was doing, but he could feel her fear radiating like heat from a stove.

Every knock on the door made her flinch. Every time he left the house, she watched from the window with an expression that suggested she expected never to see him again. The village itself was dying under the weight of German occupation intensified by Yosef’s attacks. Food rations were cut to starvation levels as collective punishment.

Public beatings became daily occurrences for minor infractions. The school was closed and converted into a detention center where suspects disappeared for days before emerging broken or not emerging at all. Joseph understood with crushing clarity that his war against the Nazis was killing his own people. Not directly, not by his hand, but the mathematics were undeniable.

Every train he destroyed provoked a response that cost Polish lives. And yet, if he stopped, the Germans would interpret it as victory. They would learn that terror worked, that collective punishment was effective, that brutality could silence resistance. The lesson they would take to other occupied territories, to other villages, to other children who might one day consider fighting back.

The moral calculus was impossible to resolve. Joseph was 13 years old now, having passed his birthday without celebration or acknowledgement, and he was grappling with questions that philosophers and military ethicists struggled to answer. Was resistance justified if it brought reprisals against innocence? Was submission morally acceptable if it meant survival? Could the end of Nazi occupation ever justify the means of getting there if those means included the suffering of the very people he was trying to save? These were not abstract questions

debated in comfortable university settings. These were life and death realities that Yosef confronted every single day. He saw the faces of those punished for his actions. He knew their names. He heard their screams in his dreams. And still, every time he held that lens up to the sun, he made the choice that resistance mattered more than safety.

That fighting tyranny was worth the cost, even when the cost was measured in innocent blood. It was a choice that would haunt him for the rest of his life, assuming he survived long enough to have a rest of his life. By late August of 1943, Joseph had become something rare and dangerous in the landscape of occupied Poland.

He was a solo operative with a proven track record of successful strikes against German infrastructure, operating without support from any organized resistance group, using methods that remained completely unknown to enemy intelligence and maintaining perfect operational security despite intense scrutiny. In modern military terminology, he would be classified as a highly effective insurgent conducting asymmetric warfare with improvised weapons.

But those terms did not exist yet, and even if they had, they would have failed to capture the essential absurdity of the situation. He was a child, a hungry, scared, traumatized child who should have been playing games and learning mathematics, and worrying about nothing more serious than childhood friendships. Instead, he was conducting a solitary war against the Third Reich, winning more often than he lost and paying a psychological price that no therapist would ever be able to fully address.

The Germans were hunting a ghost. But the ghost was bleeding from wounds that no one else could see, and he was running out of reasons to keep fighting beyond the simple fact that stopping felt like betrayal of everyone who had already died. The end of Yosef’s campaign came not from German discovery, but from the arrival of winter in early November of 1943.

The Polish countryside transformed into a landscape of gray skies and persistent cloud cover that rendered his weapon useless. Days passed without sufficient sunlight to create the focused beam necessary for ignition. The few clear days that did occur were bitterly cold with trains moving faster to avoid mechanical problems caused by freezing temperatures, giving him smaller windows of opportunity.

He attempted two strikes during this period and both failed. The weak winter sun unable to generate enough heat at the distances he needed to maintain for safety. The physics that had made him so effective during spring and summer became his limitation in autumn and winter. He was not defeated by German intelligence or superior tactics.

He was defeated by meteorology and the rotation of the earth. It was the most anticlimactic ending imaginable for a campaign that had destroyed over a dozen Nazi supply trains and diverted substantial German military resources to counterinsurgency operations in a region that should have required minimal occupation forces.

But the timing, as arbitrary as it seemed, may have saved his life. By November, the Gestapo investigation had narrowed its focus to a specific geographic area and was conducting systematic surveillance that would have eventually identified patterns in Yosef’s movements. The lead investigator, a man named Hed Stormfurer Klaus Radmaka, had begun developing a theory that the sabotur might be operating from elevated positions at extreme range, which represented dangerous progress toward the truth.

Radmaka had started mapping sightelines and sun angles, approaching the problem with scientific methodology rather than conventional counterinsurgency tactics. Given another month, he might have solved the puzzle, but the attack stopped before his investigation could reach its conclusion, and without new incidents to analyze, his superiors lost interest and reassigned him to more pressing concerns on the Eastern Front.

The mystery of the phantom sabotur remained unsolved, relegated to a footnote in regional occupation reports and eventually forgotten as the war’s momentum shifted decisively against Germany. Yosef’s campaign vanished into history not with a dramatic final confrontation, but with the quiet fade out of an unexplained phenomenon that ceased as mysteriously as it had begun.

Joseph himself survived the winter and lived to see the Soviet liberation of Poland in 1944. His grandmother died in March of that year, her heart simply giving out after years of accumulated stress and fear. He was 14 years old and completely alone in a country that had been devastated by 5 years of occupation.

The lens, his weapon and companion through months of solitary warfare, was buried with her, wrapped in cloth and placed in her folded hands. He never told anyone what he had done. Not the Soviet liberators, not the reformed Polish government, not the historians who later documented resistance activities. The idea of explaining his campaign seemed absurd in the aftermath of industrial genocide and total war.

What was one boy with a lens compared to the millions who had fought and died? How could he claim credit for strikes that had killed German soldiers and Polish civilians alike? The moral weight of his actions had no clear resolution, no satisfying narrative of heroism. Untroubled by doubt, he carried the secret silently through the remainder of his life, through the communist era in Poland, through immigration to America in the early 1950s, through marriage and children, and a career as a machinist in Detroit. He became one of millions of

displaced persons rebuilding lives in the shadow of trauma they could not discuss. Only once in 1987 did he tell his story. He was 60 years old, dying of lung cancer in a veterans hospital. when a young Polish American graduate student conducting oral histories of World War II resistance fighters interviewed him for a dissertation project.

The student, expecting conventional stories of armed partisans and underground networks, listened with growing disbelief as Yazf described focusing sunlight through his grandmother’s reading lens to destroy Nazi trains. The interview was recorded on cassette tape, transcribed, and filed in a university archive where it remained unread for decades.

No historian took it seriously. The story seemed too fantastic, too much like a tall tale told by an old man conflating memories with imagination. There was no corroborating evidence, no German records acknowledging such attacks, no other witnesses who could verify the account. Yoseph’s campaign disappeared into the vast unmarked grave of unverified wartime stories, neither proven nor disproven, just forgotten.

The truth of Yosef’s story remained buried until 2018 when a German military historian named Dr. Helena Zimmerman was researching railway sabotage in occupied Poland for a comprehensive study of partisan operations. While examining previously classified Vermachar logistics reports in the Bundes archive, she discovered a series of incident reports from the summer and fall of 1943 describing unexplained fires on fuel transport trains in a specific region of occupied Poland.

What caught her attention was not just the frequency of incidents, but the investigative notes attached to them. German engineers had examined the wreckage and found no evidence of explosive residue, no timing devices, no chemical accelerants, nothing that matched known sabotage techniques. Several reports specifically noted that attacks occurred only on clear, sunny days, and seemed to originate from elevated positions at extreme distances from the railway.

One investigator had even theorized about the possibility of concentrated solar energy as a weapon, though he dismissed his own hypothesis as physically improbable given the technology available to resistance fighters. Dr. Zimmerman cross-referenced these reports with Allied intelligence assessments and Polish resistance archives and found nothing.

No partisan group ever claimed responsibility. No Allied operation matched the timeline. The incidents remained unexplained anomalies in the historical record. Then while conducting background research on civilian life during occupation, Dr. Zimmerman discovered the interview transcript in the Wayne State University archives.

She recognized immediately that the details matched the German reports with uncanny precision. The dates aligned, the locations matched. The methodology explained the forensic mysteries that had baffled Vermacht investigators. She spent 2 years verifying every checkable element of Yosef’s account, cross-referencing train schedules, weather reports, German patrol logs, and casualty records.

Everything that could be verified was accurate. The trains he described had existed and had been destroyed exactly as he claimed. The German response he described matched occupation records. Even small details like the name of the Gestapo investigator were correct. In 2020, Dr. Zimmerman published her findings in a peer-reviewed academic journal, presenting the case that a 13-year-old boy using a reading lens had conducted one of the most unusual sabotage campaigns in military history.

The story was picked up by a handful of specialized history publications, but received little mainstream attention. It was too strange, too unlikely, too removed from conventional narratives of World War II heroism to gain traction in popular consciousness. But the story matters precisely because it is strange and unlikely and removed from conventional narratives.

Yosef’s campaign demonstrates a truth that empires throughout history have tried to suppress. Resistance does not require armies or advanced weapons or elaborate planning. It requires only determination, creativity, and the willingness to act when action seems impossible. A 12-year-old boy with no training, no support, and no resources beyond a broken lens proved that individual resistance could disrupt the machinery of industrial warfare.

He forced one of the most powerful militaries in human history to divert substantial resources to hunting a threat they could not understand or stop. He saved lives by destroying supplies that would have fueled tanks and aircraft used to kill Allied soldiers and Soviet civilians. The cost of his campaign was terrible, paid in Polish blood through Nazi reprisals, and that moral complexity deserves recognition rather than simplification.

Resistance is never clean. Heroism is never uncomplicated, but neither is submission to tyranny. The lens that Joseph used was buried with his grandmother in an unmarked grave somewhere in rural Poland. Its location lost to time and the chaos of postwar reconstruction. His own grave is in a small cemetery outside Detroit marked with a simple headstone that lists his name, his dates, and the single word machinist.

There is no mention of trains destroyed or Nazi supply lines disrupted or a child’s war fought in solitary silence. The historical record has no monuments to his campaign, no plaques marking the hillsides where he positioned himself, no textbooks teaching students about the physics of focused sunlight used as a weapon of resistance.

His story survives only in a handful of academic papers and now finally here. It survives because the truth, no matter how strange or uncomfortable, has a way of emerging from the shadows if you look carefully enough. And the truth is this. Courage is not the absence of fear or the presence of strength. Courage is a 13-year-old boy deciding that submission to evil is worse than the risk of death and then proving through action that even the smallest light properly focused can burn down the darkness.

That is the story they never told you. That is the history that was almost lost. And that is why 80 years later we remember the name Joseph and the weapon that was nothing more than his grandmother’s broken glasses and the power of the sun.