The room smelled of damp stone and cigarette smoke. A bare bulb hung from the ceiling. It swayed slightly. She had been staring at the wall for hours. Boots scraped outside. A chair moved. Papers rustled. Then she heard it. Her name spoken clearly in her own language. No accent, no hesitation.

Her shoulders tightened. Her breathing changed. Until that moment, the war had been noise and orders and slogans. This was different. This was personal. The man across the table did not raise his voice. He did not touch her. He only spoke German, calmly, precisely. The sound cut through the distance she had built to survive.

For the first time since her capture, she looked up, not because she was forced, because she was seen. By the winter of 1944, the war in Europe had entered its final and most brutal phase. Allied forces had landed in Normandy on June 6th, 1944. By August, Paris was liberated. By September, American, British, and Canadian armies pushed toward Germany’s western borders.

The German military was under extreme pressure. Manpower shortages grew. Fuel supplies collapsed. Air superiority belonged almost entirely to the Allies. Yet, resistance remained fierce. The German state mobilized everyone it could. Men, women served as clerks, radio operators, anti-aircraft auxiliaries, and intelligence support.

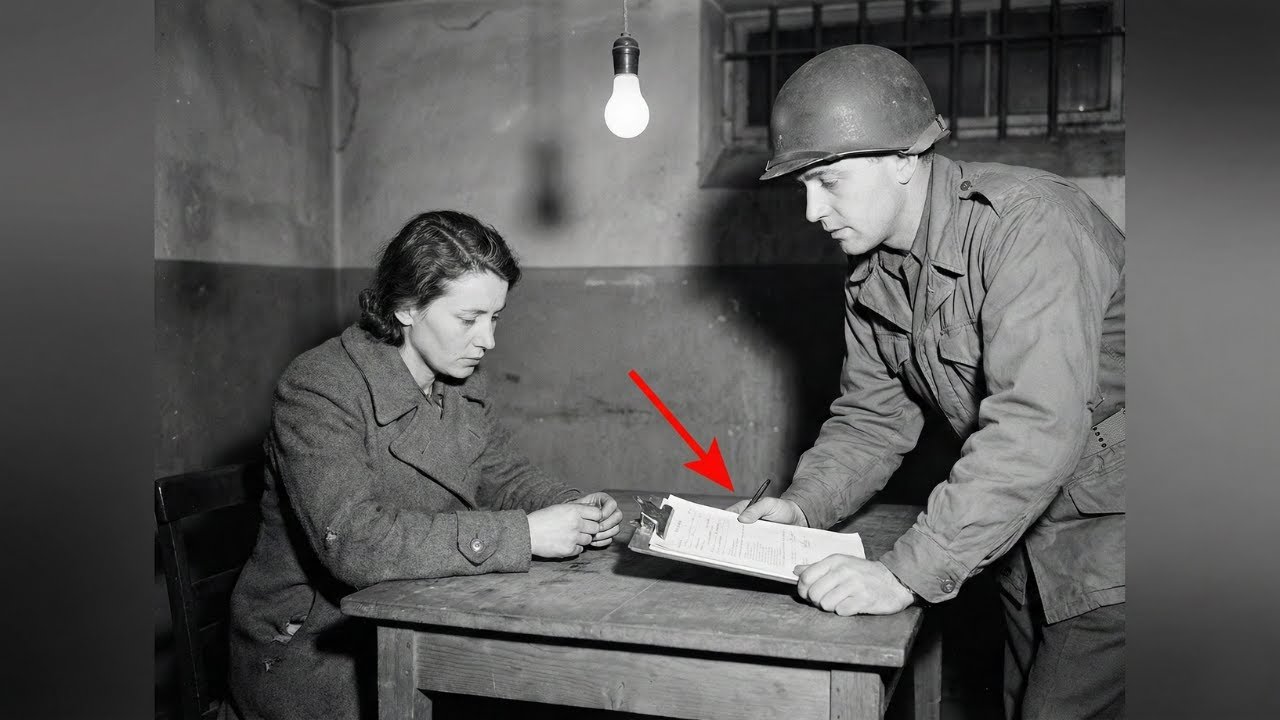

Many were not frontline soldiers, but they wore uniforms. When Allied armies advanced, these women were captured alongside male troops. The United States Army had clear procedures for prisoners of war. They followed the Geneva Convention. Prisoners were to be disarmed, registered, questioned, and transferred to holding camps.

Intelligence gathering was a priority, not through torture, but through structured interrogation. The US Army created specialized interrogation units. Many interrogators were immigrants or first generation Americans, German Jews, German Americans, refugees. They spoke fluent German. Some spoke regional dialects.

This gave them a critical advantage. Captured German personnel often expected brutality. Nazi propaganda had warned them of it. Instead, they encountered order, paperwork, and silence. For female prisoners, the shock was even greater. The German state had promised protection and purpose. Capture meant isolation and uncertainty.

Many had never left Germany before the war. Now they found themselves in foreign camps surrounded by enemies who understood their language, their ranks, and sometimes their hometowns. By late 1944, the Allied intelligence system was highly refined. Interrogation centers operated near the front and deeper behind the lines.

They cataloged units, movements, radio codes, and morale. Every detail mattered, especially as Allied planners prepared for the final push into the Reich. From the human angle, capture stripped away identity. For many German women taken prisoner, the uniform had been both shield and burden. It gave structure. It also made them targets. Once captured, rank meant little.

Gender offered no exemption. They were processed like all others, searched, registered, assigned numbers. The psychological impact was severe. Many had been raised under constant ideological pressure. Loyalty to the state was tied to survival. Breaking that loyalty was not simple. Interrogators understood this.

They did not rush. They waited. They observed posture, breathing, silence. When a prisoner heard her own language spoken naturally without hostility, it disrupted the mental barrier. It reminded her of home, of normal life, of a world beyond orders. This was not cruelty. It was method. The goal was not humiliation. It was connection.

Once that connection formed, resistance weakened. Not always, but often enough to matter. From the tactical angle, information was time. Allied units needed to know which German divisions stood ahead, where artillery was positioned, whether bridges were mined. Female auxiliaries often had access to logistical data.

They typed orders, relayed messages, filed reports. Even if they did not know full plans, they knew patterns. Interrogators focused on specifics, unit designations, command names, recent movements, supply shortages. A calm conversation in the prisoner’s native language increased accuracy. Prisoners corrected themselves.

They clarified they volunteered small details that fit into larger intelligence maps. This reduced Allied casualties, it allowed commanders to avoid strong points and exploit weaknesses. The effect was cumulative. One conversation could influence an entire sector. From the technological angle, language itself was a weapon.

The US Army invested heavily in linguistic intelligence. Training programs expanded rapidly after 1942. Manuals detailed German military structure down to insignia and abbreviations. Interrogation rooms were deliberately plain. No symbols, no flags, nothing to provoke defiance. Recording was done by hand.

Notes were cross-cheed with aerial reconnaissance and intercepted radio traffic. When a prisoner reacted to hearing her name spoken correctly, it was not chance. Interrogators often learned names beforehand from documents or other prisoners. Using correct pronunciation signaled control of information. It shifted power. The prisoner realized the enemy already knew more than expected.

Technology supported this. Files, index cards, typewriters. The system turned human reaction into usable data. From the enemy perspective, capture confirmed the collapse they feared. German propaganda had promised secret weapons and final victory. By late 1944, few believed it. Prisoners saw Allied equipment up close. trucks, radios, medical supplies, food.

The contrast was stark. Hearing German spoken fluently by an American deepened the shock. It suggested infiltration. It suggested inevitability. Some prisoners felt relief. Others felt shame. Many felt both. Breaking did not always mean betrayal. Sometimes it meant accepting reality.

For women who had served out of duty rather than ideology, the realization came faster. The war was lost. Survival now depended on cooperation. The turning point in many interrogations came quietly. There was no dramatic outburst, no raised voice. It happened when resistance no longer made sense. In late 1944 and early 1945, as Allied forces crossed the Rine, the flow of prisoners increased sharply.

Interrogation centers were overwhelmed. Efficiency mattered. Interrogators refined their approach. They began sessions in English, formal, distant. Then they shifted, a single sentence in German, clear, familiar, sometimes a name, sometimes a hometown. The reaction was immediate. Shoulders dropped, eyes moved, breathing slowed.

Once that barrier fell, information followed, not in torrance, in fragments. A unit here, a supply dump there. Over days, patterns emerged. These patterns informed Allied operational decisions during the advance into central Germany. Such intelligence helped identify under strength divisions and collapsing command structures.

It reduced uncertainty at a critical moment. The German woman who broke when her name was spoken was not unique. She was part of a system under strain. Her reaction reflected the larger collapse of a regime built on control and secrecy. The aftermath of these encounters shaped the final months of the war.

By April 1945, Allied forces met on the Elba. Germany surrendered on May 7th. Millions of prisoners were held. Female auxiliaries were processed and eventually repatriated. Interrogation records were archived. Many were later used in war crimes investigations and historical research. The intelligence gathered saved lives. It shortened the war.

The cost was immense. Over 50 million dead worldwide, cities destroyed, societies broken. For the individuals involved, the memory lingered. Interrogators remembered faces and voices. Prisoners remembered the moment the war became personal, not through violence, but through recognition. The use of language left a mark that weapons did not.

What this moment teaches is simple and hard. War is fought by systems, but it is experienced by people. Power does not always come from force. Sometimes it comes from understanding. In World War II, a shared language became a tool of clarity. It stripped away illusion. It revealed reality. The German woman who reacted to hearing her name did not change the course of the war alone.

But her response was part of a larger truth. Empires fall when control breaks at the human level. History turns not only on battles, but on moments when someone realizes they are no longer alone in their silence.