At Wizro 16 hours on 6th June 1944, Staff Sergeant Jim Walwark saw barbed wire. His horseer glider carrying 28 men and 7,000 lb of equipment was hurtling through darkness at 100 mph toward Nazi occupied France. No engine, no second chance. 47 m from the Kong Canal bridge. Six gliders. 181 men, two bridges.

10 minutes to capture them intact before the largest amphibious invasion in history began. The air inside Wallworks Glider smelled of canvas, sweat, and fear soaked wood. 26 soldiers from D Company, Second Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry sat in pitch darkness. Their commander, Major John Howard, 32 years old, was in this glider.

Lieutenant Den Brotheridge sat closest to the exit ramp, checking his Sten gun for the 40th time. Each man carried a Lee Enfield rifle, nine hand grenades, four Bren gun magazines. The glider was overloaded by 250. This was DDay’s first mission. Before the paratroopers dropped, before the bombers struck, before 156,000 men hit the beaches, six wooden gliders had to land in the dark and seized two bridges the Germans were ordered to blow up.

The bridges spanned the Kahn Canal and Riverorn, 5 mi from the Normandy coast. German defenders, 50 men from the 736th Grenadier Regiment. Behind them, the 21st Panzer Division with 127 tanks, 8 mi east, 12th SS Panza Division. If those bridges were blown, the British Sixth Airborne Division, 7,900 men, would be isolated east of the OR with their backs to the river.

German armor would have clear access to Sword Beach. The landing could fail. 156,000 Allied troops depended on whether 181 British infantrymen could land six gliders in the right field, storm two bridges in the dark, and hold them until relief arrived. This is not how you start an invasion, unless there’s no other way.

If you want history told at the moment decisions were made before outcomes were certain, subscribe now. These stories aren’t about what we know happened. there about what could have gone wrong. 90 minutes earlier at 2256 on 5 June 1940 Basau, six Halifax bombers lifted six Horser gliders from RAF Tarant Rushton in Dorsit.

Each glider 88 ft wingspan, 67 ft fuselage built mostly of plywood and canvas. Each Halifax four Bristol Hercules engines towing 15,500 lb of dead weight on a 350 ft nylon rope. Target altitude 7,000 ft. Distance to Normandy, 100 m over the English Channel. No radio communication once the tow rope released. No navigation lights. No margin for error.

Woolworth’s training had been obsessive. 54 practice sorties landing on strips 150 ft long in Devon. Night flying with goggles fitted with dark glass to simulate zero visibility. The mission required precision British planners said was impossible. Land within 50 yard of a bridge you’ve never seen at night in occupied territory in a glider with no engine that can’t go around for a second pass.

Woolwark’s response. Give me the coordinates and the wind speed. At Euro7, the six gliders crossed the Normandy coast at 7,000 ft. Cloud cover, no moon. The pilots could see nothing. At Zilbr08, the Halifax crews reached the release point. They said simply, “Cast off.” Six tow ropes released. Six gliders, now silent, began their descent into German occupied France.

Inside glider number one, Walwark felt the descent. No instruments, no altimeter, just increasing air pressure in their ears and the sound of wind over canvas. At puddle 500 ft, the ground became faintly visible. Woolwart could see the canal, a dark line cutting through darker fields. His co-pilot, John Ainsworth, was calling ranges.

1,000 yd, 800, 600. At 500 ft, Ainsworth said 400 yd. At 150 ft, Woolwark saw the bridgeg’s silhouette. Then he saw the barbed wire perimeter. Then he saw German machine gun positions. Then the ground came up. The glider hit at 100 mph. The landing skids caught the barbed wire and jerked the nose down violently. At the impact was 12 G forces.

Woolworth and Ainsworth were thrown through the cockpit’s plywood nose, landing 15 ft from the glider. The fuselage broke apart. 26 men were slammed forward into their harnesses. The glider stopped 47 m from the bridge, 15 m from the German water tower. Time zero 16 hours 6th June 1944. D-Day had begun.

Lieutenant Den Brotheridge was out of the glider in 4 seconds. He’d rehearsed this moment 40 times. Kick the door, roll left, sprint for the bridge. His platoon followed. 24 men pouring out of the shattered glider. The bridge was 190 ft long, 12 ft wide. German positions, three machine guns on the west bank, one machine gun and anti-tank gun on the east, concrete pillbox to the north.

Brotheridge ran straight at them. Two German sentries were on duty. One fired a flare gun. The flare arked over the canal, turning night into magnesium white day. The second sentry shouted, “Folsham Jagger, paratroopers!” and raised his rifle. Brotheridge shot him in the chest. Kept running. His platoon charged the bridge behind him. Sten guns firing.

German machine gunners opened fire. Tracerrounds crossed the canal at 2,700 ft per second. Brotheridge threw a grenade into the first machine gun position. The explosion silenced it. A Bren gun team opened fire on the second position, 500 rounds per minute, tearing into sandbags and flesh.

Brotheridge was halfway across the bridge when a German MG34 fired from the pillbox. He went down, kept crawling forward, threw another grenade, then collapsed. Behind him, glider number two crashed into a pond. Lance Corporal Fred Greenhow drowned. The first Allied soldier killed on D-Day. Glider number three landed intact.

Lieutenant Smith’s platoon moved toward the bridge. Smith was hit by a grenade in the first 30 seconds. Lieutenant Wood’s platoon stormed the trenches on the east bank. Wood was hit by machine gun fire. Kept giving orders from the ground. Three platoon commanders, all dead or wounded. Elapsed time 4 minutes, but deco company didn’t stop. This is what training does.

When officers fall, corporals take command. Sergeant Thornton took over one platoon led them across the bridge. They cleared trenches with grenades, fired sten guns into pillboxes at point blank range. Five Royal engineers led by Captain Jock Nielsen sprinted onto the bridge searching for demolition charges.

They found wires, cut them, found demolition charges, 120 kg of TNT stored ready but not attached to the bridge. The Germans had prepared for demolition. They just hadn’t gotten approval to complete it. By illu, 5 minutes after Walwark’s glider crashed through the wire, the Kong Canal bridge was captured. Brotheridge was dead, the first British officer killed by enemy fire on D-Day.

But the bridge was intact. At the river orn bridge 550 yards east, the mathematics were worse. Glider number six carrying Lieutenant Fox’s platoon landed 330 yd from the bridge at 0020. Glider number four was missing, landed 8 mi away. Glider number five landed 7 to 70 yd short in the marsh. Fox’s platoon ran for the bridge through darkness.

The German MG34 opened fire. Fox had one 2-in mortar. He fired. Direct hit. The machine gun exploded. The platoon crossed the bridge at full sprint. No opposition. Sweeny’s platoon arrived 90 seconds later. Both bridges captured intact by Euro War2. 6 minutes after the first glider landed. From his command post, Major Howard received the reports.

Brotheridge dead, Smith wounded, wood wounded, both bridges captured. He ordered his signaler to transmit two code words, ham and jam. Ham canal bridge captured. Jam riverbridge captured. Those two words transmitted at Y 21 on 6th June 1944 told Admiral Bertram Ramsey aboard HMS Silla that the left flank of Operation Overlord was secure.

That 156,000 men landing at Dawn had an exit route east. That German armor would have to fight through two defended bridges to reach Sword Beach. What happened next reveals the difference between British tactical flexibility and German operational paralysis. At 0120, General Litnet Wilhelm Richtor learned both bridges were captured.

He immediately called General Major Edgar Foyinger of the 21st Panza Division. Counterattack immediately retake the bridges before they’re reinforced. Fuinka agreed, then paused. Because 21st Panza was part of the armored reserve, which could only move on direct orders from OKW High Command, which meant getting approval from Field Marshall Gerd Fon Runstead, who had to ask Hitler, who was asleep, and whose staff refused to wake him because the Furer had ordered he not be disturbed before tend unless England was invaded.

England wasn’t invaded. France was. Colonel Hans Fonluck, commanding the 125th Panza Grenadier Regiment, was 8 miles from the bridges. He had 2,000 Africa Corps veterans, halftracks, armored cars. He’d personally reconited the bridges in May. He called Foinger at a 130. Request permission to advance on the canal bridges.

Foinger said, “Wait for orders from OKW.” Fonluk waited for 5 and a half hours. You’re watching history. No one teaches. Not in schools, not in documentaries, not on streaming services. This channel exists because you subscribe if this is the kind of history you want more of. Clinical, precise, no propaganda. Hit subscribe now.

At 0110, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Pine Coffin arrived with the first elements of the seventh parachute battalion. He was supposed to have 600 men. He had 100. Pine Coffin didn’t wait. He positioned his companies in Benuil and Leapor villages on the west bank facing south toward K where the German counterattack would come from.

At O2 Downs, the first German counterattack came from the north instead. Four Panzer Fi from the 21st Panza Division’s Reconnaissance Battalion moving without orders. They reached the crossroads 400 yd north of the canal bridge. The British had one working Pat anti-tank weapon, a spring-loaded tube firing a three-lb bomb, effective range 100 yd.

The Pat gunner, hidden in a ditch, waited until the tank was 50 yard away, fired. The bomb hit the tank’sammunition stowage. The vehicle exploded, turret flying 30 ft into the air. The burning tank blocked the entire road. The other three tanks withdrew. You need to understand what just happened. One British soldier with a weapon that barely worked just stopped a German armored probe.

Not because the Pat was effective. It usually wasn’t. because the road to the bridge was so narrow that one burning Panza before blocked everyone behind it. So the British didn’t win with superior firepower. They won because they controlled terrain that turned German advantages into liabilities. At 03 the 192nd Panza Grenadier Regiment attacked from the south.

Two companies, 200 men supported by 75 Witsted self-propelled guns, house-to-house fighting in Benuil. The paratroopers outnumbered 3 to one, fell back 100 yards, the Germans occupied half of Benuille, then stopped. Because their doctrine said wait for tank support, so they waited while the British reinforced. At 07, the Sword Beach landings began 6 mi west.

The naval bombardment was audible, a distant rolling thunder. Howard’s men could hear it. They couldn’t see the beach. They didn’t know if the landings were succeeding. They just knew that they had to hold until someone from Sword reached them. At dawn, German snipers appeared. Anyone moving in the open was a target.

The men of West platoon took over the captured German 75mm anti-tank gun. They used it to suppress sniper positions, firing high explosive rounds into the chatau de Benuil into church steeples into any building that offered a sight line. At 09 Z, two German gunboats came up the K canal.

The lead boat opened fire on the bridge, 20 mm rounds, tearing through sandbags. The British returned fire with everything. The pat gunner fired, missed, reloaded, fired again, hit the wheelhouse. The boat crashed into the canal bank. The second boat retreated. At 10, a lone Yunker’s due 88 bomber appeared overhead. It dropped one bomb.

The crew had orders to destroy the canal bridge. The bomb struck the bridge dead center and didn’t explode. Post battle examination showed the fuse was defective, possibly sabotaged at the factory. The German Wonder 92nd Panza Grenadier Regiment kept attacking Benuil. They brought tanks, 13 Panza Falls pushing up from Carl.

The lead tank rounded a corner into the village square. A British paratrooper armed with a gammon bomb, a canvas bag filled with 2 lb of plastic explosive ran forward, threw it under the tank’s tracks. The tank exploded, blocking the street. One by one, British soldiers with pats destroyed the other tanks from upper story windows, from doorways, from alleyways. 13 tanks destroyed.

Not because the British had better weapons, because the Germans attacked through a village where 50tonon tanks couldn’t maneuver and every window held a threat. If you believe these men, British and German, deserve to be remembered. Not as propaganda, but as they were, subscribe. These stories don’t tell themselves.

The German 21st Panza Division had 127 tanks on 6th June 1944. 13 of them, 10% of the division’s armor, were destroyed trying to retake two bridges held by 300 British infantrymen. The exchange rate, 13 tanks worth $780,000 for two British casualties and 30 expended pat rounds worth $450. At 13, the sound everyone at the bridges had been waiting for arrived. bagpipes.

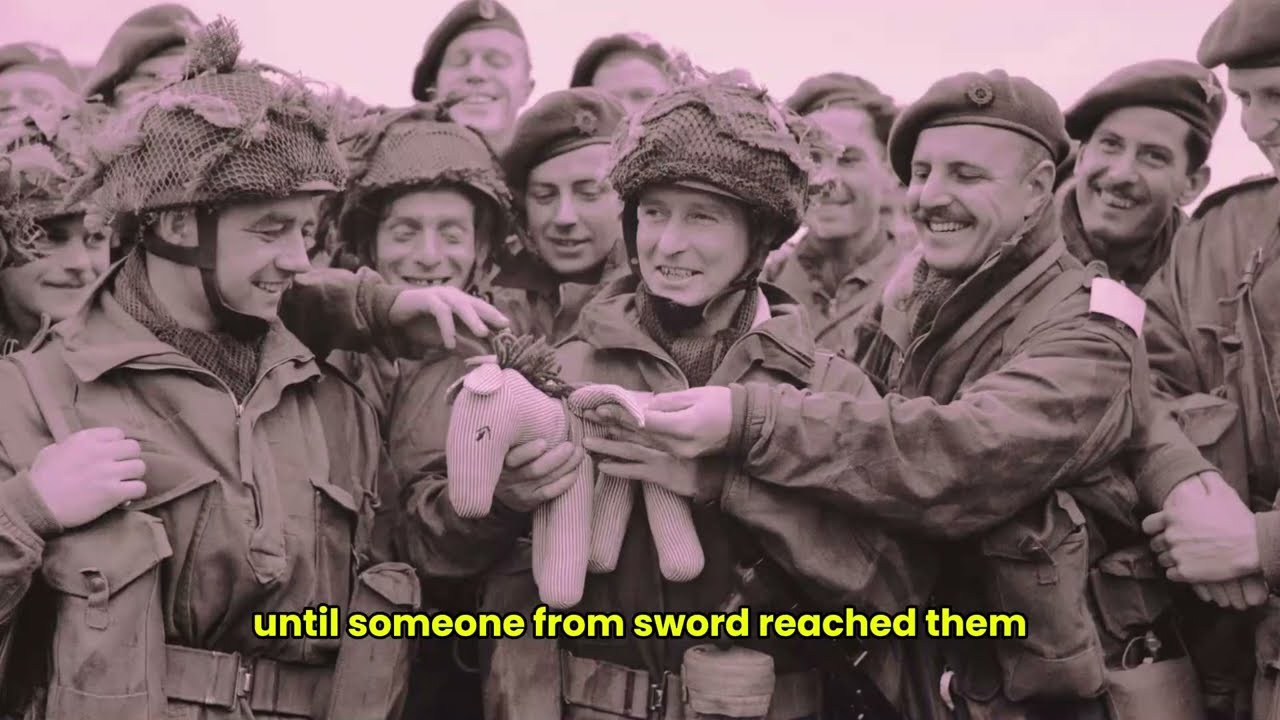

Private Bill Milan playing blue bonnets over the border marched across Pegasus Bridge at the head of Lord Loveett’s commandos. Behind them, Sherman tanks, infantry from the third division, anti-tank guns, the relief force from Sword Beach. Love met Howard on the bridge. Any casualties? Howard, covered in brick dust and cordite residue, said two dead, 14 wounded.

Lover looked at the destroyed gliders, the burning pans of the for the pockm marked concrete. He said, “Bloody marvelous. You’ve done it.” At 21:15, the second battalion Royal Warikshire regiment arrived. They took over the bridge’s defense. At midnight, Howard handed over command. His company walked through the darkness to Ranville.

By the time D company was withdrawn to England on 5 September 1944, after three months defending the bridge head, only 40 of 181 men remained. The rest were casualties, killed, wounded, or missing. The only officer still standing was Howard. The British calculated how much force was needed to capture two bridges and hold them for 13 hours.

Six gliders. 181 men cost $2,400 for the gliders. The payoff. The entire left flank of Operation Overlord secured. Without those bridges intact, the Sixth Airborne Division, 7,900 men, would have been isolated with German armor between them and the beaches. One side gave tactical commanders the authority to make decisions.

Major Howard was told what to capture and when. How he did it was his decision. He trained for 6 months, rehearsed the assault 40 times. When the plan went wrong, three platoon commanders wounded, one glider missing. Corporals took command and kept fighting.No one waited for permission. The other side had better equipment, more troops, armor superiority, defensive positions.

But Colonel Fonlak couldn’t move without permission from Fuinger. Foinger couldn’t move without permission from Runstead. Runstead couldn’t move without permission from Hitler. By the time that permission arrived at 12, 11 and 1/2 hours after the bridges were captured, British commandos and tanks from Sword Beach had already reinforced the position.

Why didn’t the Germans blow the bridges before DE company captured them? The demolition charges were stored 50 yards away, ready to attach. German engineers could have wired the bridges in 20 minutes. They didn’t because their orders said, “Prepare bridges for demolition. Do not demolish without permission from high command.” That permission chain would have taken 3 hours minimum.

The British captured both bridges in 10 minutes. The bridge head captured by the sixth airborne division became the launching point for multiple operations. Operations Atlantic and Goodwood. The battles that finally liberated CO were launched from positions secured by the sixth airborne. Air Chief Marshall Trafford Lee Mallerie called the glider landings at Pegasus Bridge the most outstanding flying achievements of the war.

Staff Sergeant Walwark put his glider 47 m from a bridge he’d never seen at night with no instruments except a compass and stopwatch in a wooden aircraft carrying £250 more than maximum rated load. The margin for error was zero. He hit zero. The awards tell you what mattered. Howard, Distinguished Service Order, Lieutenants Smith and Sweeney, Military Cross, Sergeant Thornton and Lance Corporal Stacy, Military Medal.

Lieutenant Brotheridge, mentioned in Dispatches Postuously, eight glider pilots, distinguished flying medal, not for bravery, for flying. At the Ken Canal Bridge was renamed Pegasus Bridge after the winged horse emblem of British airborne forces. The river or bridge became Horser Bridge. In 1994, the original Pegasus bridge was replaced.

The old bridge, the one wall work crashed beside, the one Brotheridge died taking. The one 181 men held for 13 hours was moved to the Pegasus Museum in Benuil. You can walk across it today. The cafe Gondre stood 30 yards from the canal bridge at Aru6. After the bridge was secured, British paratroopers knocked on their door.

The Gondres became the first French civilians liberated on D-Day. The cafe still operates. The family still runs it. British veterans visiting Normandy still gather there. Six gliders captured two bridges at Benuil in 10 minutes because the British gave tactical commanders autonomy and the Germans didn’t. And this wasn’t heroism. It was mathematics.

Six gliders had to land within 50 yards of two bridges at night. They did. 181 men had to capture those bridges in minutes. They did then hold them for 13 hours against a Panza division. They did. Every element succeeded because the plan accounted for failure. When gliders crashed, soldiers kept fighting.

When officers fell, corporals took command. When tanks attacked, infantry used terrain to negate armor. When supplies ran low, they used captured German weapons. The German failure wasn’t incompetent. Vonluck was experienced. The 21st Panza had Africa Corps veterans, but the system prevented them from acting decisively.

By the time they got permission to do what they knew needed doing, the moment was gone. The British calculated the minimum force required. 181 men, six gliders, 10 Pat rounds, and commanders authorized to make decisions without asking permission. They provided that force, nothing more. The cost, two men killed in the assault, 141 more casualties over 3 months.

The payoff, the left flank of the largest amphibious invasion in history. Pegasus Bridge proved that decentralized command could turn six wooden gliders into a strategic victory. If this stayed with you, press like. In one word, tell us what this was. Subscribe because when history stops being examined, it turns into myth.

Thank you for watching Britain in battle.