From Ridicule to Respect: How U.S. Tractors Shocked German POWs in WWII

The Laughter That Died in the Corn: How a “Slow” Kansas Tractor Shattered a German POW’s Belief in Nazi Superiority

History is typically recorded in the thunder of heavy artillery, the flash of aerial dogfights, and the signing of monumental treaties in gilded halls. But in October 1943, on a quiet, windswept farm outside Camp Concordia, Kansas, one of the most significant intellectual surrenders of World War II took place. It didn’t involve a white flag or a military tribunal. It involved a 50-year-old farmer named Earl Morrison, a green-and-yellow John Deere tractor, and a 24-year-old German prisoner of war named Werner who was about to discover that everything Berlin had taught him about the “weakness” of the American system was a lie.

Werner was a product of the Old World. Before being captured in the North African theater, he had spent his life working his family’s farm near Munich. In his world, farming was an art form of precision and collective labor. Small plots, horses, hand tools, and a village-wide effort were the only way to survive. To Werner, the American farmer he watched from the camp fence was an object of ridicule—a symbol of a “soft” nation that relied on clunky, slow machines because it lacked the grit for real manual labor.

The Mockery at the Fence Line

“Look at this inefficiency,” Werner remarked to his friend Klaus as they watched Earl Morrison drive his tractor at what seemed like a snail’s pace. “In Germany, we would have twenty men with scythes, and we would be twice as fast. American machinery is all show and no substance.”

Around them, other German prisoners laughed in agreement. They had been indoctrinated with the belief that American industry prioritized quantity over quality, producing cheap, disposable goods that could never match the superior craftsmanship of the Reich. They believed that while the Americans might have big machines, they lacked the systems to make them truly effective. They were about to learn that “fast” is not the same as “productive,” and that “perfect” is often the enemy of “victorious.”

The 500-Acre Revelation

The lesson began when Earl Morrison put the prisoners to work. Werner and his fellow Germans expected the grueling, dawn-to-dusk manual labor they knew from home. Instead, Morrison introduced them to a mechanical corn picker. As the tractor moved methodically through the field, the machine stripped the ears from the stalks, sorted them, and dumped them into a trailing wagon in one continuous motion.

Werner remained skeptical. “It’s slow,” he muttered.

Through a translator, Morrison offered a simple, quintessentially American rebuttal: “I’m not trying to win a race. I’m trying to harvest 500 acres before the first frost.”

Werner froze. He did the math in his head. His family’s farm in Bavaria was 12 acres. It took their entire family and several hired hands weeks of back-breaking work to harvest. This man, sitting alone on a machine, was talking about 500 acres as if it were a routine chore. “Impossible,” Werner said. “One man cannot do this.”

Earl Morrison simply smiled and said, “Watch.”

The Math of Total War

Over the next two weeks, the laughter at the fence line was replaced by a heavy, contemplative silence. Werner watched as the “slow” tractor moved across the landscape with a relentless, methodical persistence. It didn’t get tired. it didn’t need a lunch break from twenty people. It just kept going.

By the end of the first week, Morrison had harvested more corn than Werner’s entire village in Germany produced in a full season.

The realization hit Werner like a physical blow. He began to ask questions that would have been considered treasonous in Munich. One evening at the barn, he approached Morrison: “Where does all this corn go? 500 acres is more than our village needs for a year.”

Morrison leaned against the tractor tire. “This corn? Some feeds my cattle. Some goes to the grain elevator to be shipped to Chicago and New York. Some goes to the military. Some goes to our allies. We all feed into the system.”

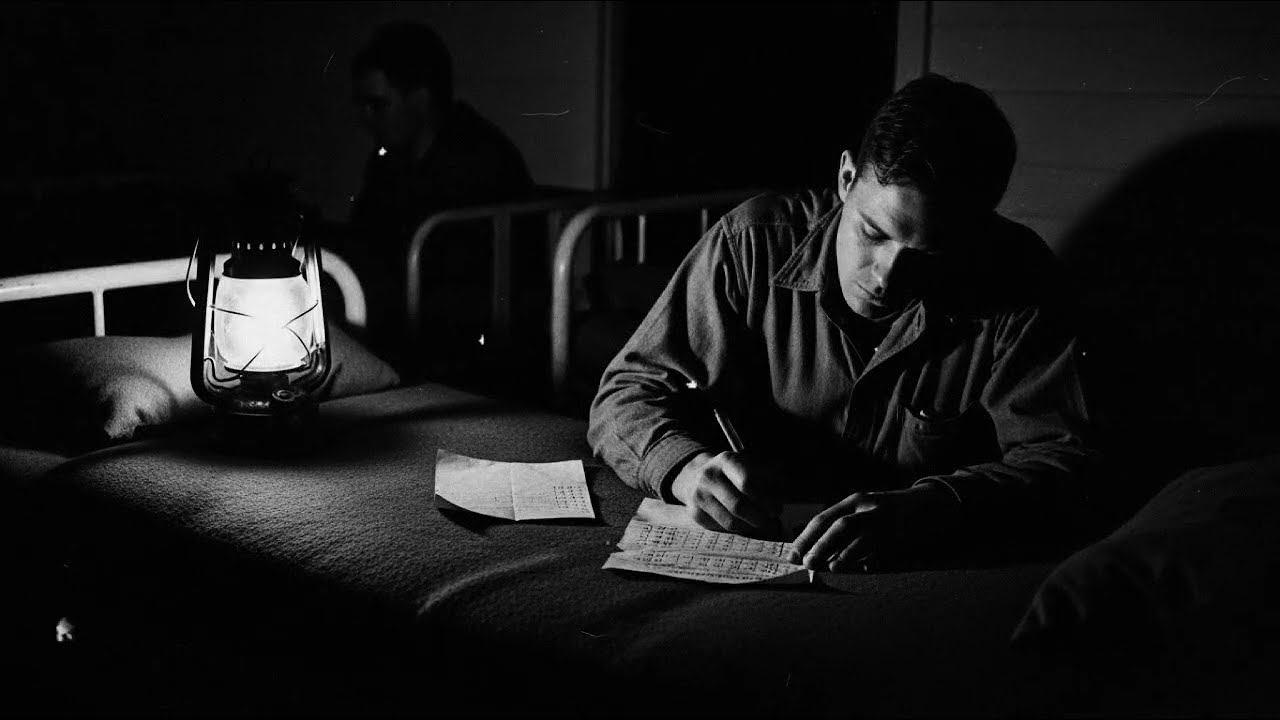

That night, Werner couldn’t sleep. He sat in his barracks at Camp Concordia, doing calculations in the dark. If every American farm was this size, this mechanized, and this productive, the numbers were staggering. He realized that America wasn’t just fighting a war; they were fueling a global machine while maintaining a food surplus.

“We were taught American industry was weak,” he whispered to Klaus. “But this tractor isn’t weak. It just works differently than we work. And it works better.”

The Genius of Imperfection

One afternoon, Werner watched as Morrison repaired a broken part on the tractor. In Germany, agricultural equipment was often hand-crafted; if a part broke, you needed a master craftsman to fabricate a replacement. But as Werner watched, Morrison simply pulled a standardized part from a crate and swapped it in. The parts were clearly labeled and interchangeable.

“In Germany,” Werner observed, “only a craftsman can fix this.”

Morrison nodded. “That’s the point. Craftsmanship is beautiful, but we need systems that work even when things break—and even when people aren’t perfect.”

This concept—the “Genius of Imperfection”—became the focal point of Werner’s transformation. He realized that German engineering prided itself on being the best in the world, but it required a high level of expertise at every stage. American engineering, conversely, assumed that things would break and that operators would be unskilled. It designed standardized systems that could be maintained by anyone, anywhere. It was a philosophy of scalability that the German High Command had completely overlooked.

The Silent Surrender at the Grain Elevator

The final blow to Werner’s worldview came when Morrison took him into town to the grain elevator. Werner stood in awe as trucks from dozens of local farms lined up, each dumping thousands of bushels of corn into massive silos.

The elevator operator explained that they processed roughly 2 million bushels a season from just 40 farms. Werner’s entire region in Germany, with hundreds of small farms, didn’t produce that much combined.

“This is why you’re winning the war,” Werner said quietly to the translator. “You can fight and feed yourselves and your allies, and still have a surplus. We cannot compete with this.”

Earl Morrison looked at the young soldier with a gravity that bypassed the language barrier. “It’s not about competition, son. It’s about systems. We built infrastructure, machines, banks, and rails that all connect. Any one piece isn’t that impressive. But together? Together they work.”

A Legacy of Systems

Werner returned to his barracks that night a changed man. He gathered the other prisoners who worked the local farms. “We need to talk about what we’re seeing,” he told them. “The machines are slow, but they never stop. One American farmer produces what twenty German farmers produce, not because he is better, but because his system is better.”

The lessons Werner learned in the cornfields of Kansas stayed with him long after the war ended. When he was eventually repatriated to Germany, he brought with him a new understanding of scale, standardized parts, and system thinking. He became a proponent of agricultural modernization in post-war Germany, helping to rebuild his nation’s food supply using the very “scalable” principles he once mocked at the fence line of a Kansas prison camp.

Earl Morrison continued to farm his 500 acres until his retirement, likely never knowing the full psychological impact he had on the young man from Munich. But the story of the “slow” tractor remains a powerful testament to the industrial might of the American heartland. It proved that in a conflict of nations, the ultimate weapon isn’t always a bomb or a bullet—sometimes, it’s a system that works even when the world is falling apart. Werner had come to America to witness a “soft” nation; he left realizing he had witnessed a machine that could not be stopped.