“Black Poison”: How a Bottle of Coca-Cola Terrified German Child Soldiers and Revealed the Lie at the Heart of the Third Reich

CAMP SHELBY, MISSISSIPPI, 1944 – The heat in Mississippi in July is not merely a weather condition; it is a physical weight. It presses down on the pine forests and red clay with a suffocating humidity that turns the air into soup. For the men of the U.S. Army stationed at Camp Shelby, it was a miserable fact of life. But for the prisoners of war arriving in cattle trucks, it was a descent into a hell they had never imagined.

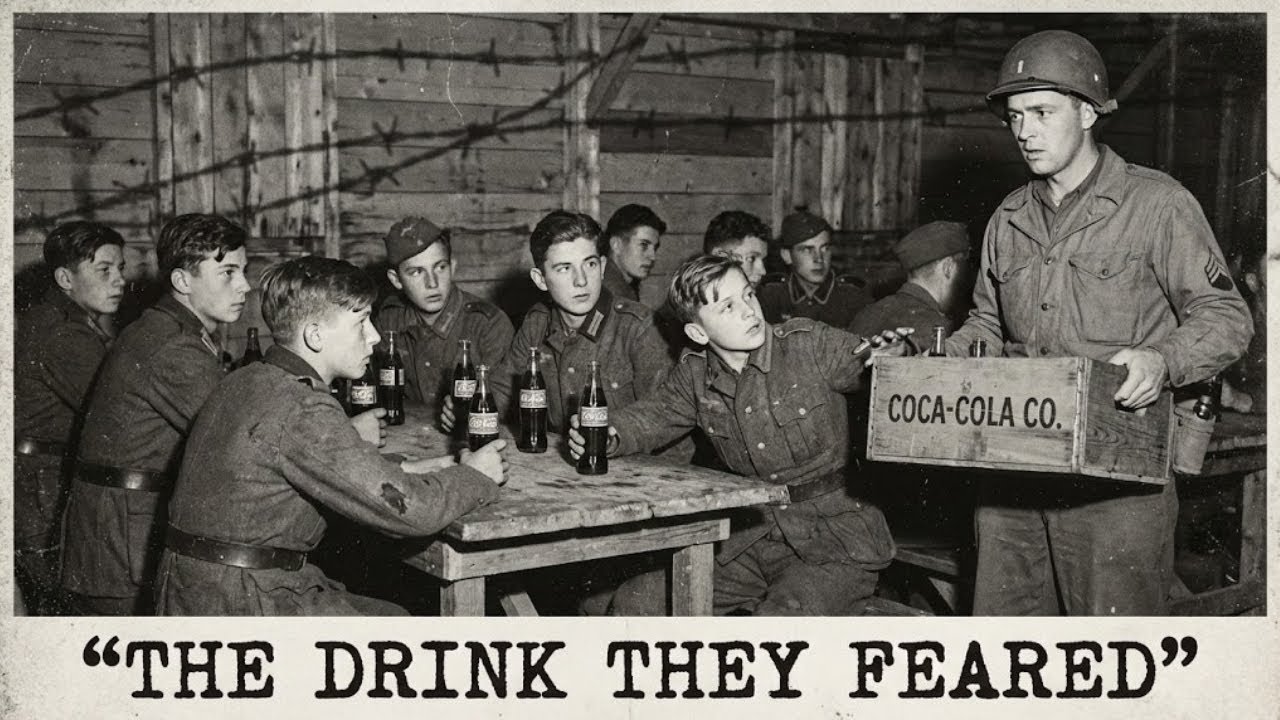

On July 18, 1944, Corporal James Henley was walking the perimeter wire on a routine patrol. In his hands, he carried a wooden crate that clinked with the promise of salvation: twelve glass bottles of ice-cold Coca-Cola, beads of condensation rolling down their sides like sweat.

Inside the wire sat a row of new arrivals. They were not the hardened desert foxes of Rommel’s Afrika Korps who had populated the camp for the last year. These prisoners were different. They were smaller, frailer. Their uniforms hung off their skeletal frames like costumes three sizes too big. They were boys—some as young as 15 or 16—plucked from the 12th SS Panzer Division “Hitlerjugend” and thrown into the meat grinder of Normandy before being shipped across the Atlantic.

Henley, a man with younger brothers back home in Georgia, felt a pang of pity. He stopped at the gate and pulled a dripping bottle from the crate. He thrust it through the chain-link fence, offering it to the nearest boy, a 16-year-old named Hans Erdman.

He expected gratitude. He expected a smile.

Instead, the boy recoiled. His eyes went wide with terror, and he scrambled backward in the dust, whispering a single word that Henley couldn’t understand but felt in his bones: “Gift.”

In English, it means a present. In German, it means poison.

This is the true story of the cultural collision that took place behind the barbed wire of American POW camps, where a simple bottle of soda became a weapon of psychological warfare, a currency of survival, and the ultimate proof that the Third Reich was doomed.

The Children of the Lie

To understand why Hans Erdman looked at a bottle of Coca-Cola and saw death, one must understand the world he came from. Hans was born in 1928. He had literally never known a Germany without the swastika. From the moment he could walk, he was marched. From the moment he could read, he was fed a steady diet of propaganda.

The Nazi machine had taught him that the Aryan race was invincible, that the Führer was a god, and that the enemy—specifically the Americans—were a degenerate, mongrel race who relied on trickery because they lacked courage.

But the propaganda went deeper than just racial hatred. It created a terrifying mythology about American cruelty. These boys were told that American soldiers didn’t take prisoners; they tortured them. They were told that Americans used chemical weapons and biological agents disguised as food or medicine. “They smile while they kill you,” the officers had warned them. “They offer gifts that are traps.”

Hans had arrived in Mississippi with a bandaged head, the result of a mortar blast near Caen. He had spent the 11-day Atlantic crossing seasick and terrified, waiting for the torture to begin. Now, standing in the oppressive heat, a man in an American uniform was offering him a dark, bubbling liquid in a glass grenade. It smelled sweet, but so did phosgene gas.

To Hans, this wasn’t a drink. It was a test.

The “Black Honey”

Corporal Henley stood frozen, the bottle hovering in the space between the two worlds. He didn’t speak German. He didn’t know about the indoctrination. He just saw a kid who looked like he was about to pass out from heatstroke refusing the only relief available.

Sergeant Mike Rossi, a guard who spoke a smattering of German, walked over to investigate the commotion. He listened to the frantic whispers of the boys huddled in the dirt.

“They think it’s poison, Jim,” Rossi said, shaking his head in disbelief. “They think we’re trying to kill them.”

Henley looked at the bottle. He looked at the boys. The absurdity of it washed over him. He was holding the most American object on earth—a symbol of leisure and simple pleasure—and these kids thought it was a war crime.

So, Henley did the only logical thing. He twisted off the metal cap. The carbonation hissed—a sound that made the prisoners flinch. He tilted his head back and drained half the bottle in three long, glugging swallows. He wiped his mouth, let out a loud, satisfied burp, and smiled.

“It’s just soda, kid,” he said. “Just sugar and bubbles.”

Hans Erdman watched the guard closely. He didn’t die. He didn’t convulse. He wasn’t foaming at the mouth. In fact, he looked refreshed. The sweat on his forehead seemed less severe.

Slowly, with a trembling hand, Hans reached through the wire. He took the cold glass. The tactile sensation alone was a shock—ice-cold in a world of heat. He lifted it to his lips.

The first sip was a revelation.

Germany had been on a war footing for years. Real sugar had vanished from the shelves around 1942, replaced by metallic-tasting saccharine and ersatz substitutes. Hans had forgotten what actual sugar tasted like.

The Coke hit his tongue with a sharp, stinging fizz and an explosion of sweetness that felt almost illegal. It was bright, sharp, and aggressively alive. He drank again, greedily this time, draining the bottle until he was tipping it vertically to catch the last drops.

He lowered the bottle and looked up at Henley. The fear in his eyes had been replaced by something else—a child-like wonder.

“Gut,” Hans whispered. “Good.”

The Currency of the Camp

Within minutes, the crate was empty. The dozen boys sat in the shade, dazed by the sugar rush and the cooling relief. The fear of “poison” evaporated, replaced by a desperate craving for more.

Word spread through Camp Shelby like wildfire. The Americans had a drink—a dark, bubbling elixir—that tasted like liquid candy. The prisoners dubbed it Schwarzes Amerikanisches Honig—”Black American Honey.”

By the end of the week, Coca-Cola had become the unofficial currency of the prisoner population. The U.S. military provided prisoners with a ration of cigarettes, usually Lucky Strikes. Hans, who didn’t smoke, discovered he could trade his pack for two bottles of Coke. A carton could buy a whole case.

The guards, amused by the obsession, played along. “You want some Black Honey, Hans?” they would tease. It became a bonding ritual, a way to bridge the gap between captor and captive.

But for Hans and his comrades, the obsession was about more than just the taste. It was about the realization of what the drink represented.

The Impossible Math of Defeat

In Nazi Germany, every resource was strained. Fuel was scarce, food was rationed, and luxuries were nonexistent. The entire society was geared toward the grim necessity of survival.

Yet here was the enemy, the “degenerate” Americans, handing out glass bottles of sugar water to their prisoners.

Hans began to ask questions. His English improved rapidly as he conversed with the guards. He asked Henley where the drink came from. Henley explained that the Coca-Cola Company had pledged to supply every American serviceman with a Coke for 5 cents, no matter where they were in the world. Bottling plants followed the army. There were factories running 24 hours a day just to make soda.

“For every plane you built, we built ten,” Henley told him one afternoon. “For every tank, fifty. For every bottle of soda… millions.”

Hans stared at the empty bottle in his hand. He was holding the physical proof of his country’s defeat. The realization was crushing. Germany couldn’t even supply its troops with winter boots, while America was shipping caramelized sugar water across the ocean just to keep morale high.

The math was impossible. The propaganda films of American breadlines and poverty were lies. The “decadent” enemy was actually an industrial juggernaut so wealthy it could afford to be generous to the people trying to kill it.

“We cannot win,” Hans said quietly to Henley. It wasn’t a question. It was the acceptance of a new reality.

The Old Guard Breaks

In late September, a new group of prisoners arrived at Camp Shelby. These were not the terrified children of the Hitler Youth; these were hardened veterans, men in their 30s and 40s who had fought on the Eastern Front before being transferred to France. They were true believers, encased in armor of cynicism and loyalty to the Führer.

When they saw the young boys drinking Coke and singing “You Are My Sunshine” with the guards, they were disgusted. They spat on the ground. They refused the “Yankee sludge” on principle, calling the boys traitors and weaklings.

For two days, the veterans drank only tepid water from the camp taps. They sat in the sweltering heat, glaring at the traitorous luxury of the soda bottles.

Then, the Mississippi weather played its final card. A late-summer heatwave struck, pushing temperatures to 98 degrees with humidity that made the air feel like a sauna.

By the afternoon of the third day, the resolve of the “master race” crumbled in the face of dehydration. Sergeant Mike Rossi watched as the veterans, one by one, began to sheepishly trade their cigarettes. They drank quickly, hiding the bottles, ashamed of their weakness.

But once they started, they couldn’t stop.

One evening, Hans found himself sitting next to Feldwebel Otto Krauss, a 32-year-old veteran. Otto held a half-empty bottle of Coke, staring at it with a look of profound defeat.

“Do you know what this means?” Otto asked in German, his voice rough.

Hans nodded. He knew.

“We fought the wrong war,” Otto whispered. “Or we fought the right war for the wrong side.”

They drank in silence as the sun set over the Mississippi pines. Thousands of miles away, their cities were burning, their leaders were screaming about “Final Victory,” and their armies were disintegrating. But here, in the quiet of the camp, the truth was clear. The enemy had won long ago, not just with bombs, but with logistics. With supply chains. With sugar.

A Legacy in a Bottle

Corporal Henley shipped out to the Pacific in November 1944. Before he left, he gave Hans a parting gift: a full case of 24 bottles.

“You take care of yourself, kid,” Henley said. “War’s almost over. You’ll go home soon.”

Hans rationed that case like it was gold, drinking one bottle every three days. The last one was finished in February 1945, just months before the German surrender.

When Hans finally returned to Germany in late 1945, he found a wasteland. His hometown was rubble. His father was dead. His mother was starving. The stark contrast between the abundance of Camp Shelby and the devastation of his homeland was a shock that never left him.

Years later, in the 1950s, the economic miracle of West Germany began to take hold. Coca-Cola returned to the country, this time not as a mysterious contraband, but as a symbol of the new, free world.

Hans Erdman stood in front of a store window and saw the familiar red logo. He bought a bottle. He cracked it open, and the sound—that sharp hiss—transported him instantly back to the wire fence in Mississippi.

It tasted exactly the same.

It tasted like the day he learned the truth.

Corporal Henley survived the war and returned to Georgia. He lived a quiet life, rarely speaking of his service. But in his wallet, tucked behind photos of his wife and children, he kept a small, black-and-white snapshot. It showed a skinny German boy behind a wire fence, holding up an empty glass bottle and smiling.

It was a reminder of the strange, human moments that happen in the midst of inhumanity—when a sip of soda proved that even in a world poisoned by lies, the truth can still be sweet.