The doctor peels back the boy’s lips and sees something that makes him step back. The gums are black and swollen, bleeding at the slightest touch. Teeth that should be white and solid are loose in their sockets, several already missing. The boy’s name is Matias. He is 18 years old, and his body is covered in bruises that appeared without any impact.

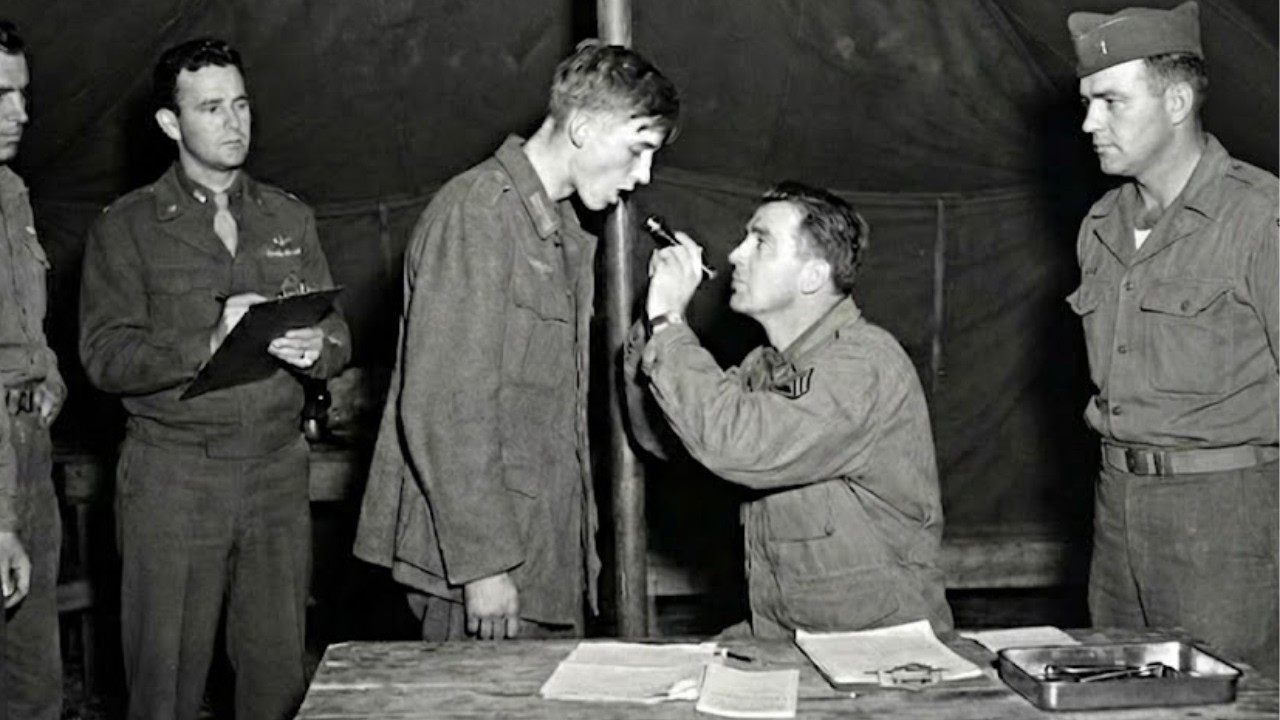

When Dr. James Harrington presses gently on Matias’s shin. The skin stays indented for several seconds, like pressing into soft clay. This is severe scurvy, a disease that should not exist in 1945. A disease that sailors got centuries ago when they spent months at sea with no fresh food. But Matias is not a sailor.

He is a German prisoner of war who arrived at an American camp in Louisiana. And the question that shocks everyone is not what he has, but how he got it. We are at Camp Livingston in Louisiana in April 1945, 3 weeks before the war in Europe ends. The camp holds approximately 5,000 German prisoners of war.

Most of them captured in North Africa or Italy. They work on farms, in lumber camps, and in road construction crews across the South. The prisoners are generally healthy, fed according to Geneva Convention standards, and treated reasonably well compared to prisoners in other theaters of the war. Disease is rare at Camp Livingston.

The camp hospital treats broken bones from work accidents, occasional infections, and seasonal illnesses, but nothing exotic or alarming until Matias arrives. Matias comes in on a truck from a smaller work camp about 50 mi north, a logging operation run by the Army Corps of Engineers. The camp supervisor sent him down with a note saying the boy is too sick to work and needs medical attention beyond what the work camp can provide.

Dr. James Harrington reads the note and expects something routine, maybe severe flu or an infected injury. When Matias steps down from the truck, Harrington sees immediately that this is not routine. The boy moves like every step hurts. His face is pale with a gray undertone. His eyes are sunken and ringed with dark circles.

His uniform hangs loose on a frame that looks too thin. Harrington directs two orderlys to help Matias into the hospital and prepare an examination room. The examination begins with the basics. Matias is 18 years old, 5’9 in tall, and weighs 117 lb. That weight is low, but not catastrophic. Harington has seen thinner prisoners.

What concerns him more are the visible symptoms. Matias’s skin is covered in small purple and red spots, some the size of pin pricks, others as large as dimes. These are patiki and perura, signs of bleeding under the skin. There are larger bruises on his arms and legs that Matias says appeared on their own. No trauma, no impact.

His legs are swollen from the knees down, the skin stretched tight and shiny. When Harrington asks Matias to open his mouth, he sees the blackened gums and the loose teeth. Harrington has read about scurvy in medical textbooks, but he has never seen a case this advanced. He calls over his senior nurse, a woman named Margaret Flynn, who has been working at the camp since it opened, and asks if she has ever seen anything like this. She shakes her head.

Neither of them has. We are still in the examination room, and Harrington is working through the differential diagnosis. The bleeding under the skin, the gum disease, the joint pain Mias describes, and the swelling all point to one condition. Scurvy caused by severe and prolonged vitamin C deficiency. Vitamin C is essential for the body to produce collagen, the protein that holds tissues together.

Without it, blood vessels become fragile and leak. Gums deteriorate, old wounds reopen, bones weaken. In extreme cases, internal bleeding can be fatal. Scurvy was common among sailors and explorers in the age before refrigeration and canned goods. But it is virtually unheard of in the modern era, especially in a prisoner of war camp where rations, even if monotonous, are supposed to include enough vitamins to prevent deficiency diseases.

Harrington orders blood tests to confirm the diagnosis, but the camp laboratory is not equipped to measure vitamin C levels directly. He has to rely on clinical judgment. The combination of symptoms is unmistakable. This is scurvy, advanced, and untreated. The question now is how Matias developed it. Harrington asks Matias through an interpreter how long he has been at the logging camp. Matias says 4 months.

What did he eat there? Matias describes a diet of bread, beans, potatoes, and occasionally meat. No fruit, no vegetables except potatoes. No fresh food of any kind. Harrington asks if the other prisoners at the logging camp ate the same diet. Matias nods. Harrington makes a mental note to report this to the camp commonant immediately.

If Matias has scurvy from the work camp diet, there are probably other prisoners developing the same condition. Harington explains the diagnosis to Matias in simple terms through the interpreter. Matias has a disease caused by not eating enough of the right foods, specifically foods with vitamin C. The treatment is straightforward.

Give him vitamin C and fresh food and the symptoms will reverse. But Harrington also warns Matias that recovery will take time. The gums will heal slowly. The bruises will fade, the swelling will go down, but the damage that has already been done, the lost teeth and the weakened bones cannot be fully repaired. Matias listens without much reaction.

He seems more exhausted than concerned, as if understanding the diagnosis takes more energy than he has left. We are still at the camp hospital on the first day of Matias’s arrival and Harrington is designing a treatment plan. The primary intervention is simple. Massive doses of vitamin C. Harrington orders the camp pharmacy to prepare ascorbic acid tablets and he instructs the kitchen to provide Matias with orange juice, tomatoes, and any other fresh produce available.

The camp normally serves fresh vegetables and fruit to prisoners in accordance with Geneva Convention standards, but the work camps scattered across Louisiana operate under looser oversight. Some work camp supervisors, especially those in remote logging operations, prioritize productivity over prisoner welfare and cut corners on rations.

Harrington suspects this is what happened to Matias. Harrington starts Matias on 200 mg of vitamin C three times a day, far above the normal daily requirement of about 50 mg. He also orders fresh orange juice with every meal and raw tomatoes as a side dish. Within 24 hours, Matias reports that the joint pain is slightly less severe.

Within 48 hours, the gums stop bleeding as much when he brushes his teeth. The bruises take longer to fade, but no new ones appear. The swelling in his legs begins to decrease by the end of the first week. Harrington documents every change meticulously. This is not just a medical case. It is evidence of a systemic failure in the work camp system.

On the third day, Harrington reports the case to Colonel Martin Evers, the camp commandant. Evers is a career officer who runs Camp Livingston by the book and takes prisoner welfare seriously, partly out of principle and partly because violations of the Geneva Conventions could lead to retaliation against American prisoners held by Germany.

Evers listens to Harrington’s report and asks the key question. Is this an isolated case or a pattern? Harrington says he does not know yet, but if the logging camp fed all prisoners the same diet Matias described, there could be dozens of men in early stages of scurvy. Evers orders an immediate inspection of the logging camp and instructs the camp medical staff to screen every prisoner who returns from work details for signs of vitamin deficiency.

Evers also drafts a report to his superior officers at the regional army command, flagging the scurvy case as a potential violation of prisoner treatment standards. We are now one week into Matias’s treatment, and he is strong enough to tell his full story. We need to go back to understand how an 18-year-old German soldier ended up in a logging camp in Louisiana with a disease from the age of sailing ships.

Let us go back 8 months to August 1944 in France. Matias was part of a rerealon supply unit attached to a Vermach division trying to hold a defensive line near the Lir River. He had been in uniform for only 4 months. Drafted in April 1944 as Germany scraped the bottom of its manpower reserves. His unit was poorly trained, underequipped, and demoralized.

When American forces broke through the line, Matias’s unit disintegrated. Some men fled east. Others surrendered. Matias and about 30 others were captured in a farmhouse where they had taken shelter. The American soldiers who captured Matias’s group were part of an infantry division moving fast toward Paris.

They did not have time or resources to process prisoners properly. Matias and the others were disarmed, searched, and marched to a temporary holding area in a field surrounded by barbed wire. They stayed there for 2 days with minimal food and no shelter. Then they were loaded onto trucks and moved to a larger prisoner collection point near the coast.

From there, they were put on a liberty ship bound for the United States. The voyage took 9 days. Conditions on the ship were crowded, but tolerable. Matias was fed twice a day, mostly bread and canned meat. There were no fresh vegetables or fruit, but the trip was short enough that vitamin deficiency was not yet a concern.

Matias arrived in the United States in September 1944 and was processed through a large intake center in New York. He was delically screened, photographed, and assigned a prisoner number. The medical screening was cursory, a quick check for obvious illness or injury. Matias passed. He was then sent by train to Camp Livingston in Louisiana, where he spent two months in the main camp doing light labor like kitchen work and grounds maintenance.

During those two months, Matias was healthy. He ate regular camp meals that included vegetables, occasional fruit, and a balanced mix of proteins and carbohydrates. He gained weight. He felt stronger. He even started learning basic English from the guards. Then in December 1944, he was selected for a work detail at the logging camp and everything changed.

We are still tracing Matias’s path backward. And now we arrive at the logging camp where the scurvy developed. The camp is a temporary facility in the pine forests of northern Louisiana set up to harvest timber for the war effort. The Army Corps of Engineers runs the operation and the labor force is a mix of about 60 German prisoners and 20 civilian workers.

The camp consists of a few barracks, a mess hall, a tool shed, and a small administrative building. There is no hospital, only a first aid station staffed by a medic with basic training. The work is hard. Prisoners fell trees with saws and axes, strip branches, load logs onto trucks, and clear brush. The hours are long, usually 10 to 12 hours a day, 6 days a week.

The work is physically demanding, and the caloric needs of the prisoners are high. The problem is the food. The camp supervisor, a civilian contractor named Leonard Prescott, is responsible for feeding the prisoners. Prescott is paid a fixed amount per prisoner per day, and he has figured out that he can pocket the difference if he keeps costs low.

He buys the cheapest food available: flour, beans, lard, potatoes, and occasional cheap cuts of meat. He avoids fresh vegetables and fruit because they are more expensive and spoil quickly. The prisoners eat the same meals day after day, bread, boiled beans, fried potatoes, and sometimes a thin stew. There is no variety, no color, no vitamin C.

The prisoners complain, but Prescott ignores them. The guards, most of whom are older men, not fit for combat duty, do not intervene. They eat better food trucked in from town and do not pay attention to what the prisoners are getting. Matias spends four months in this routine. Wake at dawn. Work until midday. Eat a meal of bread and beans. Work until dusk.

Eat another meal of potatoes and thin stew. Sleep. Repeat. For the first two months, Matias does not notice any symptoms. His body uses the vitamin C reserves stored in his tissues. But by the third month, those reserves are depleted. He starts feeling tired all the time. His muscles ache. His gums bleed when he chews hard bread. Small cuts take longer to heal.

He mentions these symptoms to the camp medic who gives him aspirin and tells him to toughen up. By the fourth month, the symptoms are severe. The bruises appear. The teeth loosen. The leg swelling starts. Matias can barely walk without pain. He tells the medic again, and this time the medic realizes something is seriously wrong.

He reports to Prescott who finally agrees to send Matias to Camp Livingston for proper medical care. Prescott does not send anyone else. He does not change the diet. He just removes the problem prisoner and goes back to business. We return to the present at Camp Livingston where Colonel Evers has ordered an investigation into the logging camp.

A medical officer and two military police officers drive up to the camp unannounced one morning and demand to inspect the facilities and examine the prisoners. Prescott is caught off guard and tries to delay them, but the officers have orders from the regional command and will not be put off. They tour the camp, inspect the mess hall, review the food inventory, and examine every prisoner.

The findings are damning. Out of 60 prisoners, 12 show early signs of scurvy, bleeding gums, small bruises, joint pain, and fatigue. Another 20 show signs of general malnutrition, weight loss, lethargy, and poor wound healing. The food stores in the camp contain no fresh vegetables, no fruit, and no vitamin supplements.

The officers confiscate the camp’s financial records and find evidence that Prescott has been systematically underspending on prisoner rations and pocketing thousands of dollars over the past 6 months. Let us know in the comments where you are watching this from. Are you in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, or somewhere else? We would love to know who is keeping these stories alive.

Prescott is arrested on the spot and charged with misappropriation of government funds and violation of the Geneva Conventions. The prisoners are immediately transferred back to Camp Livingston where they are medically evaluated and treated. The logging operation is shut down pending a full investigation. Evers sends a detailed report up the chain of command and the case eventually reaches the desk of the inspector general’s office in Washington. The scandal is kept quiet.

The army does not want public attention on a case that makes the United States look like it is violating international law. Even if the violation was caused by one corrupt contractor, Prescott is court marshaled in a closed proceeding, found guilty, and sentenced to two years in federal prison.

The prisoners affected by the scurvy outbreak are given medical care and bet her rations. Matias becomes the poster case for what went wrong. We are now 3 weeks into Matias’s treatment at Camp Livingston, and the improvements are remarkable. His weight has increased to 129 lbs. The gums have stopped bleeding and are beginning to return to a healthy pink color.

The loose teeth have stabilized, although three teeth that were already too damaged have fallen out. The bruises on his skin have faded from dark purple to yellow green and are slowly disappearing. The swelling in his legs is gone. Matias can walk without pain. He can work light duty in the camp vegetable garden. A job that Harrington assigned partly for physical rehabilitation and partly for the symbolic irony of having the scurvy patient tend to the very foods that are curring him.

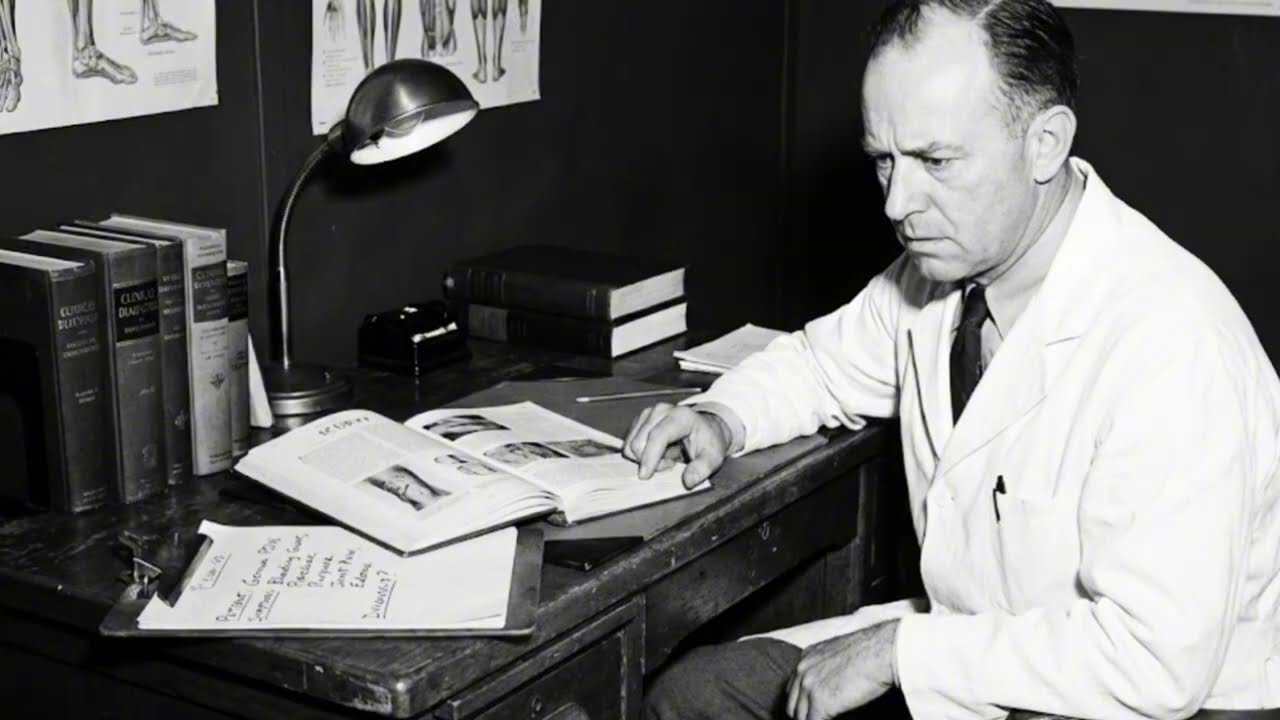

Harrington continues to monitor Matias closely and documents the recovery process. He is writing a case study for the Army Medical Journal, partly to educate other doctors about scurvy diagnosis and treatment and partly to create a permanent record of the failure at the logging camp. The case study includes photographs of Matias’s gums before and after treatment, charts showing the progression of symptoms, and detailed notes on the vitamin C dosing protocol.

Harrington hopes the case study will lead to better oversight of work camp nutrition and prevent future outbreaks. He knows the military bureaucracy is slow to change, but he believes documentation matters. If you are enjoying this story and want more untold accounts from World War II prisoners of war, make sure to subscribe to the channel.

We are bringing you stories that most history books never covered. Matias himself seems quietly grateful for the treatment, but he does not talk much about his time at the logging camp. When other prisoners ask him what happened, he says simply that the food was bad and he got sick. He does not mention Prescott by name or describe the conditions in detail.

Matias is not interested in revenge or justice. He is focused on survival and on the fact that the war will be over soon. He listens to the camp radio and hears the news from Europe. The German army is collapsing. American and Soviet forces are closing in on Berlin. It is only a matter of days or weeks now.

Matias wonders what he will go home to, if there will even be a home to go back to. Let us pause Matias’s personal story and look at the bigger picture of prisoner of war health and nutrition. During World War II, the United States held over 400,000 German prisoners in camps across the country by the war’s end.

The vast majority of these prisoners were treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions, which required that prisoners receive the same quality and quantity of food as the capttor nation’s own troops. In practice, this meant that German prisoners in American camps generally ate better than German civilians or soldiers in Germany during the final years of the war.

The typical camp diet included meat, bread, vegetables, fruit, milk, and occasional treats like coffee or cigarettes. Malnutrition was rare and deficiency diseases like scurvy were almost unheard of in the main camps. The problem was the work camps. Thousands of prisoners were sent to temporary work sites across the country, especially in the South and the West, where they provided labor for agriculture, forestry, road construction, and other projects.

These work camps operated under less supervision than the main camps, and some were managed by civilian contractors who had financial incentives to cut costs. The army issued regulations requiring work camps to provide adequate nutrition, but enforcement was inconsistent. Some contractors followed the rules. Others, like Leonard Prescott, exploited the system.

The result was scattered cases of malnutrition, vitamin deficiency, and disease that should not have existed in a wealthy country with abundant food supplies. Scurvy specifically was extremely rare among prisoners of war in American custody. Medical records from the period show fewer than 50 documented cases out of hundreds of thousands of prisoners.

Most of those cases, like Matiases, occurred in remote work camps with poor nutritional oversight. The mortality rate from scurvy in American camps was zero. All documented cases recovered with vitamin C treatment. This stands in stark contrast to other theaters of the war where scurvy and other deficiency diseases killed thousands of prisoners.

Japanese camps in the Pacific, German camps on the Eastern Front, and Soviet camps holding German prisoners all experienced widespread malnutrition and deficiency disease. The fact that scurvy was so rare in American camps is a credit to the overall system. But cases like Matias’s reveal that the system was not perfect and when oversight failed, prisoners suffered.

We are still at Camp Livingston, and Harrington is thinking about the ethical dimensions of Matias’s case. The medical treatment was straightforward. The cure for scurvy has been known for centuries. Give the patient vitamin C and the disease reverses. But the larger questions are harder. How did a system designed to protect prisoners fail so badly that an 18-year-old boy developed a disease from the age of wooden ships? Who is responsible? Prescott is being held accountable legally, but Harrington knows the failure goes deeper. The Army

Corps of Engineers placed prisoners under Prescott’s supervision without adequate oversight. The regional command did not inspect the logging camp regularly. The guards at the camp did not report the poor conditions. The system had multiple failure points and Matias fell through all of them. Harrington also thinks about the other prisoners at the logging camp, the ones who showed early signs of scurvy, but were not as severely affected as Matias.

They are recovering now, but they went through months of unnecessary suffering because one man decided to steal money meant for their food. Harrington wonders how many other camps have similar problems that have not been discovered yet. He sends a memo to the regional medical command recommending mandatory monthly inspections of all work camps with specific attention to food quality and prisoner health.

He does not know if the recommendation will be implemented, but he feels obligated to try. The ethical complexity deepens when Harrington considers Matias’s perspective. Matias is a German soldier, an enemy combatant who fought for a regime that committed atrocities. But he is also an 18-year-old kid who was drafted, captured, and then neglected by the system that was supposed to protect him as a prisoner of war.

Harrington does not have strong feelings about the war itself or about German guilt. His job is medicine, not politics. But he believes that once someone becomes a prisoner, they are entitled to humane treatment regardless of what side they fought on. That is the principle of the Geneva Conventions and it is the principle Harrington follows.

Matias is not just a case study. He is a patient who deserves care and dignity. We are now in early May 1945 and the war in Europe is over. Germany has surrendered unconditionally. The news spreads through Camp Livingston on loudspeakers and in shouted conversations across the yard. Prisoners gather in groups, some crying, some silent, some arguing about what comes next.

Matias hears the news while working in the vegetable garden. He sets down his hoe and sits on the ground for a long time. He does not cry. He does not celebrate. He feels a strange emptiness as if something that defined his life for years has suddenly disappeared and left a hole. The war is over, but the problems are not.

Germany is destroyed. His family’s fate is unknown. His future is uncertain. The end of the war does not bring clarity. It brings more questions. Over the next few weeks, the routine at Camp Livingston shifts. Work details continue, but the intensity decreases. The guards are less strict. The atmosphere is less tense.

Prisoners start thinking about repatriation, about going home, though no one knows when that will happen. Matias continues his recovery. His weight has reached 135 lbs, close to a healthy range for his height. His gums are fully healed, except for the gaps where teeth are missing. He has adapted to eating with fewer teeth, and does not complain.

Harrington examines him one final time and declares him fit for regular duty. Matias thanks Harrington through the interpreter. A simple thank you that does not capture the depth of what the doctor did for him, but it is all Matias has to offer. What does Matias’s story tell us about World War II and the treatment of prisoners of war? On one level, it is a story about a system that mostly worked but had cracks.

The United States treated German prisoners better than most other nations treated their prisoners during the war. The camps were generally humane. The food was adequate and the medical care was available, but the system was not perfect. Work camps operated with less oversight, and some contractors exploited that lack of oversight.

Matias fell through one of those cracks and nearly died from a disease that should not have existed in 1945. The fact that he survived and recovered is a testament to the medical care he eventually received, but it does not erase the months of suffering that should never have happened. On another level, Matias’s story is about resilience.

He survived the logging camp, the scurvy, the uncertainty of captivity, and the chaos of returning to a destroyed country. He rebuilt his life without bitterness or self-pity. He did not seek recognition or compensation for what he went through. He simply moved forward. That kind of resilience is easy to romanticize.

But it is also important to recognize that Matias should not have needed it. The system failed him and he endured the consequences. His resilience is admirable, but the failure that required it is not. The scurvy case also raises questions about how we remember history. The major events of World War II, the battles and the political decisions are well documented and widely known.

But the small stories, the individual experiences of ordinary soldiers and prisoners are often lost. Matias’s case survived because Dr. Harrington documented it and published a case study. Without that documentation, Matias would be just another name in a prisoner list and the failure at the logging camp would be forgotten. Documentation matters. Records matter.

They create accountability and they preserve the human details that give history its texture and meaning. We end where we began, in the examination room at Camp Livingston in April 1945. Matias is 18 years old. His gums are black and bleeding. His skin is covered in bruises. And Dr. Harrington is trying to understand how a prisoner of war in the United States developed severe scurvy.

The answer, as we now know, is a combination of neglect, greed, and systemic failure. One man, Leonard Prescott, decided to steal money meant for prisoner food. The oversight system failed to catch him in time. Matias and 11 other prisoners paid the price with their health. The medical exam shocked everyone because scurvy was not supposed to exist in 1945.

Certainly not in a country as wealthy as the United States and certainly not in a prisoner of war camp that was bound by international law to provide adequate nutrition. But the shock was also about what the scurvy revealed. It was not just a medical condition. It was evidence of a deeper problem, a reminder that systems are only as good as the people who operate them and that even the best designed systems can fail when oversight is lacking.

Matias’s scurvy was preventable. It never should have happened. The fact that it did happen and that it took 4 months for anyone to intervene is a failure that deserves to be remembered. Not to assign blame decades later, but to understand how failures occur and how they can be prevented. Matias survived. That is the most important fact.

He recovered from the scurvy, went home, rebuilt his life, and lived into old age. His story is not a tragedy, but it is not a triumph either. It is simply a life marked by suffering and resilience, by failure and recovery. The medical exam shocked everyone. But what happened after the exam, the slow healing, the return home, the quiet persistence of a man who refused to disappear is what gives the story its lasting significance.

Matias was not a hero. He did not change history, but he lived through history. And his story, preserved in Dr. Harrington’s case notes reminds us that history is made up of millions of individual lives, each one worth remembering.