Living Beside Bigfoot for 30 Years: The Creature’s Prophecy About Humanity’s Future Revealed in an Unforgettable Sasquatch Legend

Up where the Skagit River runs cold and the mist clings to the Douglas firs like the ghosts of old loggers, there is a story they tell about the man at the end of the road.

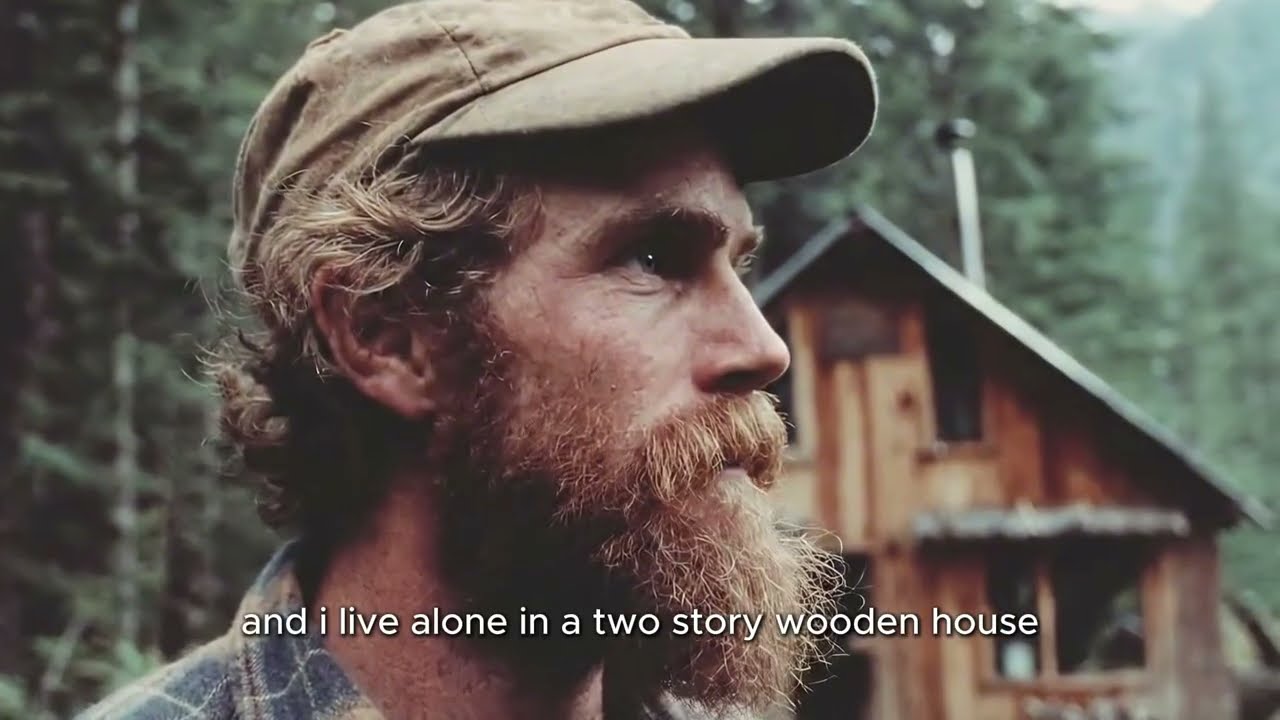

They say if you drive east from Concrete, past where the pavement turns to gravel and the gravel turns to mud, you might find a clearing carved out of the green wall of the Cascades. There sits a house of hand-cut timber, weathering gray under the relentless Washington rain. And on the porch sits a man named Shea, old as the mountain roots now, waiting for a friend who will never return.

He is the keeper of a secret history, and the bearer of a terrible prophecy. But to understand the end of the world, you have to understand how the friendship began.

It started in the autumn of 1982, the season of dying light. Shea Patterson had come to the high country to run away. He was a man who had spent his life building cages of concrete and steel—bridges, highways, overpasses—until his own life collapsed under the weight of noise and sorrow. He fled the city, seeking the silence of his grandfather’s land, forty acres of isolation surrounded by a forest so thick it swallowed the sun.

He wanted to be alone. The woods, however, have eyes.

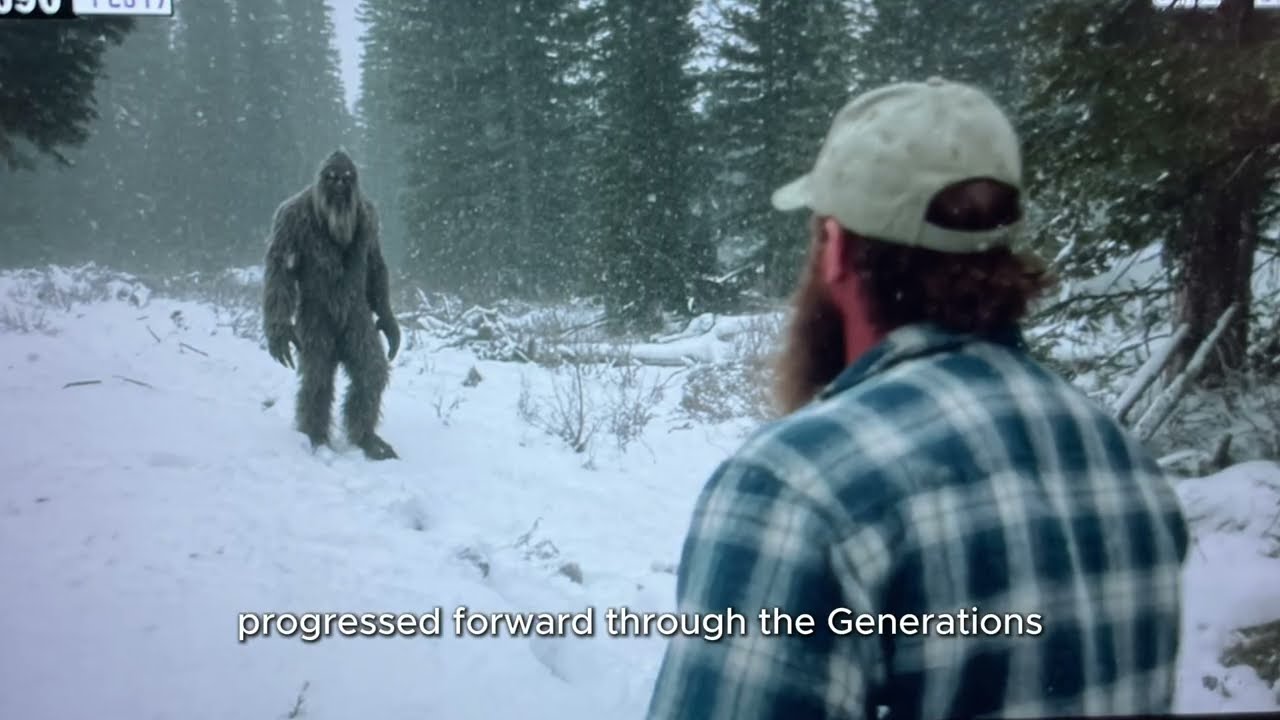

It happened on a morning when the fog lay heavy on the ground, masking the world in white. Shea was splitting firewood, the crack of the axe the only sound in the valley. Then, the hair on his arms stood up. The primal brain, the lizard part that remembers when men were prey, whispered: Turn around.

He turned.

Standing at the edge of the trees, where the tame grass met the wild dark, was a giant.

It was not a bear. It stood on two legs, seven feet of shadow and muscle, cloaked in fur the color of wet bark and storm clouds. It was the creature the tribes called Sasquatch, the thing the city men called a myth. But to Shea, standing there with his axe frozen in his hand, it was simply real.

The giant did not roar. It did not charge. It watched him with eyes that held a shocking, human intelligence. They were amber eyes, old and weary. And then, the impossible happened.

The creature raised one massive hand, palm open. It waved.

It was a gesture of peace. A gesture of recognition. I see you. You see me.

Shea, his heart hammering against his ribs like a trapped bird, raised his own trembling hand. “Hello,” he whispered to the mist.

The giant lowered its hand, turned with the grace of a deer, and vanished into the fog.

That winter was hard, but it was not lonely. A silent commerce began between the man and the beast.

Shea found a river stone on his porch, perfectly round and smooth as an egg. In return, he left a loaf of fresh bread on a stump. The bread vanished; a twist of cedar boughs appeared. Honey was traded for a piece of driftwood shaped like a salmon.

They were testing each other. Are you safe? Are you kind?

By November, the giant stopped hiding. He would come to the edge of the clearing at dusk, while Shea sat on the porch with his kerosene lamp. The creature—whom Shea began to call “Elder,” for the silver that streaked his muzzle and the heavy, slow way he moved—would sit cross-legged in the snow.

They sat together in the blue twilight, separated by fifty feet of air and a million years of evolution. Shea would talk. He spoke of his failed marriage, of the cities that ate the sky, of his loneliness. Elder would listen, tilting his massive head, his breath pluming in the cold air.

But Elder had not come just for company. He had come because he was running out of time.

One evening, as the snow began to fall in earnest, Elder brought a stick. He smoothed a patch of snow and began to draw.

He drew a circle. He pointed to the sun. He drew a wavy line. He pointed to the creek. He drew a vertical line with branches. A tree.

It was a lesson. Shea, a man of science and blueprints, became a student again. Night after night, under the freezing stars, the beast taught the man the Old Tongue—not a language of words, but of symbols. A circle meant whole. A broken line meant pain. A cluster of marks meant many. A mark crossed out meant gone.

Shea learned quickly. He learned that Elder was not just an animal living in the woods. He was a historian. He was a scientist of the soil. And he was the last of his kind.

The lesson that haunted Shea the most was the Timeline.

Elder would draw a long line in the snow. He would mark the past—generations ago—where the symbol for his people (a stylized upright figure) was abundant. The forest symbols were thick. The salmon symbols crowded the rivers.

Then, he moved the stick forward. He drew triangles—the symbol for the Stone Men, the humans. As the triangles multiplied, the trees thinned. The salmon vanished. And the symbols for Elder’s kin were crossed out, one by one.

Gone. Gone. Gone.

Then Elder drew the present. He placed a pattern of stones that counted to fifteen. Fifteen of his kind left in the entire mountain range.

But he didn’t stop there. He drew the future.

He extended the line just a little further—fifty years, perhaps. A blink of an eye in the life of a mountain.

At the end of the line, the symbol for the Sasquatch was gone entirely. Extinct.

But next to it, the symbol for the Stone Men—the humans—was also crossed out.

The water symbols were broken. The sun symbol was angry, surrounded by heat lines. The web of life, which Elder drew as a great interconnected net, was torn to shreds.

Shea sat on his porch, shivering not from the cold, but from the message.

“You’re saying we die too?” Shea asked, his voice shaking. “You’re saying we are killing the world, and it will kill us back?”

Elder looked at him with those ancient, amber eyes. He made a gesture: hands interlocked, then pulled apart violently. Connection broken.

He was saying: You tear the web, you fall through the hole.

Spring came late that year, the meltwater roaring down the creeks. Elder looked frail. His movements were stiff, and his breath rattled in his chest. He was dying, his body wearing out after seventy years of watching his world disappear.

One evening in May, Elder did not sit. He stood at the edge of the trees and beckoned.

Shea grabbed his lantern and his coat. He followed the giant into the deep woods, past the boundaries of his grandfather’s land, into the old-growth timber where the trees were wide as silos.

They walked for hours, moving through the dark like ghosts. Finally, they reached a place where three massive cedars grew in a triangle, guarding a wall of rock. Elder pushed aside a curtain of moss, revealing a fissure in the stone.

He squeezed through. Shea followed.

It was a cathedral of silence. The cave was dry and cool, and when Shea raised his lantern, the light danced across the walls.

Shea gasped.

The walls were covered in art. Thousands of symbols, carved and painted, stretching from the floor to the high ceiling. Some were faded with age, etched by hands that had been dust for centuries. Others were fresh charcoal, black and sharp.

It was a library.

“This is your history,” Shea whispered.

Elder moved to the center of the room and spread his arms. All of it.

He walked Shea through the archive. Here were the records of the great fires. Here were the counts of the elk herds going back three hundred years. Here were the star charts, marking the cycles of the moon and the sun.

And here was the tragedy.

The newer sections were a chronicle of collapse. The arrival of the loggers. The damming of the Skagit. The poisoning of the water. The decline of the People of the Wood.

Elder pointed to a section at eye level. It showed two lines running parallel. One was the health of the forest; the other was the health of the Sasquatch. They dropped together.

Then, he pointed to a third line: Humanity. It rose high, climbing steeply, consuming everything. But then, abruptly, it plummeted.

Elder picked up a piece of charcoal. He drew a mark on the wall, representing the present day. Then he drew a short distance forward. He marked a threshold.

The Point of No Return.

He looked at Shea. He pointed to the wall, then to Shea’s head, then to his mouth.

Witness. Speak.

“You want me to tell them,” Shea said. “You want me to warn them.”

Elder nodded. He placed his heavy hand on Shea’s shoulder. It was a transfer of burden. We could not stop it, the touch seemed to say. We were too few. You are many. You must try.

They left the cave as the moon rose. Elder walked Shea back to the edge of the clearing.

The giant was exhausted. He leaned against a fir tree, his chest heaving. He reached into a pouch woven from cedar bark and pulled out a small object. He pressed it into Shea’s hand.

It was a carving. A piece of yellow cedar, whittled with a sharp stone into the likeness of a Sasquatch. It was exquisite, capturing the sadness and the dignity of the Old One.

“I will keep it,” Shea promised, tears freezing on his cheeks. “I will keep the cave. I will tell the story.”

Elder looked at him one last time. He raised his hand in that familiar wave. Then, he turned and walked into the shadows. He did not look back.

Shea waited for weeks, watching the tree line. But the forest was empty.

In late autumn, Shea returned to the cave alone. He found a new mark on the wall, fresh and final. The symbol for End of Life.

Elder had gone into the deep woods to die, leaving his library in the care of the only human he had ever trusted.

Shea Patterson did not go back to building bridges. He became a builder of warnings.

For forty years, he tried. He wrote books under pseudonyms. He wrote letters to universities. He brought a young scientist named Michael Torres to the woods, teaching him to read the forest not with machines, but with the eyes of the Elder. They published papers on “cascade effects” and “ecosystem collapse,” using the data from the cave without ever revealing its source.

Some listened. Most did not.

The world moved on. The cities grew. The summers got hotter. The smoke from the wildfires turned the moon red. The salmon runs collapsed, just as the symbols on the wall had predicted.

Now, Shea is seventy-eight years old. His heart is failing, echoing the rhythm of a dying world. He sits on his porch, the cedar carving smooth in his hand from years of worry.

He looks at the timeline Elder drew in the cave. The date of the collapse—the point where the web unravels completely—roughly aligns with the year 2033.

Eight years left.

He writes his final testimony by the light of the same kerosene lamp. He writes of the giant who waved. He writes of the library in the stone. He writes of the terrible, beautiful burden of knowing the future and watching it happen.

“I have kept the promise,” he whispers to the empty clearing. “I bore witness.”

The trees stand silent. The mist rolls in off the Skagit, cold and indifferent.

Shea Patterson leaves his notebook on the table. He stands, his joints aching, and walks to the edge of the porch. He looks out at the dark wall of the forest, searching for a shadow that isn’t there.

He raises his hand. He waves.

And if you listen closely, in the silence between the wind and the rain, you might hear the forest wave back—a sigh of branches, a creak of wood, a final farewell from a world that is waiting to see if we will wake up before the dark comes down for good.