February 10th, 1945. 4:47 p.m. Philippine Sea. A twin engine transport appears on the horizon. American markings, white star on the fuselage, descending toward an island airirstrip. Lieutenant Louis Kurd sees it from 3,000 ft and his stomach drops. That airirstrip belongs to the Japanese. The transport is a Douglas C-47 sky train. 12 people on board. Crew of four.

Eight passengers. Two of them are army nurses. They have no idea where they’re landing. Kurds dives. Keys his radio. American transport. You are approaching a Japanese airfield. Pull up. Pull up immediately. He tries again. Nothing. Their radio is dead. The C-47 continues its descent. Landing gear down.

Flaps extended. 150 ft above the runway. Below, Japanese anti-aircraft gunners track Kurds through their sights. They’re not shooting at the transport. They think it’s one of theirs. A captured prize coming home. They’re shooting at him. Kurds has 15 seconds. If that plane lands, 12 Americans will spend the rest of the war in a Japanese prison camp.

He’s read the intelligence reports. Baton, the death marches, the beheadings. Most of them won’t survive. He pulls behind the C-47. Lines up his gun sight on the left engine and opens fire. Louie Edward Kurds grew up in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Born November 2nd, 1919. His father, Walter, sold real estate. His mother, Esther, taught school.

Middleclass family. Nothing remarkable, but he kept looking up. spent hours at Smithfield watching biplanes take off and land. By the time he enrolled at Purdue University in 1938, he already knew what he wanted. December 6th, 1941, a Saturday, Kurds walks out of his Purdue dormatory and into a recruiting office.

Third year of college, drops out, enlists in the Army Air Forces. He doesn’t know about Pearl Harbor. Nobody does. That’s tomorrow. 24 hours later, recruiting stations across the country are mobbed. Six-month waiting lists. Thousands of young men fighting for a handful of training slots. Kurds is already in the system. While America scrambles to build an air force, he’s learning to fly.

By December 1942, he has his wings and a gold bar. Second lieutenant, 23 years old, orders to North Africa. The army hands him a Lockheed P38 Lightning. The P38 is unlike anything else in the American arsenal. Twin engines, twin booms, top speed 414 mph, 450 caliber machine guns, and a 20 mm cannon, all mounted in the nose.

German pilots call it the forktailed devil. Kurds paints a cartoon devil on his nose, gives him a halo, names the plane Good Devil. He joins the 82nd Fighter Group, 95th Fighter Squadron. His first combat mission is 9 days away. April 29th, 1943, Mediterranean Sea. Standard escort mission, protect the bombers, don’t play hero.

12 Messers BF 109’s drop out of the sun. The BF 109 is the backbone of the Luftvafa. Single engine, single seat, 398 mph, two 13 mm machine guns, and a 20 mm cannon firing through the propeller hub. The pilots flying them have been at war since 1939. Spain, Poland, France, Britain, Russia. Four years of combat experience against the best pilots Europe had to offer.

Louie Kurds has been in a combat zone for 9 days. He shoots down three of them. First kill, a diving attack from above. His tracers walk across the 109’s engine cowling. The German rolls and drops toward the sea. White foam spreading on blue water. Second kill. He spots a P38 in trouble. Kurds breaks formation. Dives into the fight.

His cannon rounds tear through the Messersmid’s wing route. The German spins out. Third kill. The 109’s wingman tries to escape. Kurj follows him down to 500 ft. A 3-second burst. The Messersmid cartwheels into the waves. Three kills. First mission. His squadron commander doesn’t know whether to promote him or ground him. May 1943.

Two more kills over Sardinia. That’s five. He’s an ace. Four weeks of combat. June 24th, 1943. Something different. Kurd spots a fighter he doesn’t recognize. Sleek, fast Italian markings. A Maki C202 Folore. Italy’s best, more maneuverable than the BF 109. Pilots who face them say they’re the most dangerous thing in the Mediterranean.

What follows is a threeminute knife fight at 15,000 ft. Turns, reversals. The P38 has more power. The Mackey has tighter turning radius. Kurds wins by going vertical. He pulls up, stalls over the top, and drops onto the Mackey’s tail. One burst. The Fulgore comes apart. Six victories, two different air forces. August 1943. Two more BF 109s fall to his guns.

Eight confirmed kills. He’s one of the deadliest pilots in the Mediterranean, and his luck is about to run out. August 27th, 1943, Naples. The mission is straightforward. Escort B25 bombers to their target. Keep the Germans off them. Come home. The Germans have other plans. 50 fighters, BF 109s, and FW190s. A wall of aircraft rising to meet them.

The P38s are outnumbered 4 to one. Standard doctrine says disengage. Protect the bombers. Don’t get drawn into a fight you can’t win. Kurds hears a distress call. One of his wingmen,three 109’s on his tail. 30 seconds from dying, he breaks formation into 50 German fighters alone. He gets two of them, but the third 109 gets behind him.

Cannon rounds punch through the left engine. The P38 shutters. Fire warning light. The lightning comes down hard on a beach. Belly landing. Sand spraying everywhere. He has maybe 5 minutes before patrols arrive. Kurds grabs his 45 pistol, sets the P38 on fire, runs for the treeine. The Italians catch him before sunset. The P camp is chaos.

Italy is tearing itself apart. Mussolini deposed. The new government secretly negotiating surrender. German troops flooding south. September 3rd, 1943. The radio crackles. Italy has signed an armistice. The guards know what’s coming. The Germans will take over the camps. The Gustapo will arrive. They make a decision that saves Curtis’s life.

The guards open the cells, hand out rifles, point toward the mountains, go. 20 Allied officers walk out. Americans, British, Canadians, all with the same destination, Allied lines. The problem, Allied lines are 150 mi south through the Aenine Mountains, through German occupied territory on foot in winter. The Aenines run down Italy’s spine like a wall. Peaks over 9,000 ft.

Dense forests. No roads except the ones the Germans control. No shelter except what you can find. No food except what strangers give you. Kurds [snorts] and his group travel at night. 5 miles on a good night. Two on a bad one. They navigate by stars when the sky is clear, by compass when it’s not.

By guesswork when the compass fails. Sleep comes in caves, in barns, in abandoned shepherd huts with holes in the roof. Food comes from Italian farmers who risk execution to help them. A loaf of bread here, some cheese there, never enough, always given with fear in the eyes and a finger pressed to the lips.

Sencio, the Germans shoot anyone who helps escaped prisoners. Communist partisans find them in October. Resistance fighters waging guerilla war since Mussolini fell. They provide guides, safe routes around German checkpoints. Catholic priests hide them in monasteries. Ancient stone buildings where no one asks questions. Where Latin prayers echo off walls that have stood for a thousand years.

The winter of 194344 is brutal. Snow 6 ft deep in the passes. Temperatures below zero for weeks. Most of them are wearing the same clothes they were captured in. One man dies along the way. A British wing commander pneumonia. They bury him in an unmarked grave and keep moving. 9 months. They walk for 9 months.

On May 27th, 1944, Louie Kurd stumbles into Allied lines at Monte Casino. The battle there has been raging since January. The monastery is rubble. The hillsides are covered with the dead. He’s wearing Italian peasant clothes. Hasn’t shaved in months. Speaks English with an accent from nine months of hiding.

The centuries almost shoot him as a spy. Back in Fort Wayne, his parents have a telegram. Missing in action, presumed dead, his mother has already held the memorial service. Louisie Kurds walks back from the grave. Most men would take the ticket home. nine months behind enemy lines. P escaped, walked his 150 miles through German occupied territory.

That’s enough war for anyone. Kurds volunteers for more. There’s a catch. The Geneva Conventions prohibit escaped PS from fighting in the same theater. If the Germans recapture him, they could torture him for information about the partisans, the farmers, the priests, everyone who helped him escape. Their lives depend on Kurds staying out of Europe. Fine, he’ll find another war.

August 1944, the Pacific. New squadron. Fourth fighter squadron. Third Air Commando Group. New base, the Philippines. New aircraft, a P-51D Mustang. The Mustang is the war’s perfect fighter. A Packard built Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, 1,490 horsepower. Top speed 437 mph at 25,000 ft. Range 1,650 mi with drop tanks.

650 caliber machine guns with enough ammunition for 18 seconds of continuous fire. Faster than his P38. More agile, longer range. He names it bad angel, the opposite of good devil. Light and dark, Europe and Pacific. Something about that name feels like prophecy. February 7th, 1945. Southwest of Formosa. Kurds spots a twin engine aircraft at 12,000 ft.

Japanese markings. A Mitsubishi K46 code named Dena. Fast, unarmed, built to run. Kurds doesn’t give it the chance. One burst, the K46 explodes. Seven German planes, one Italian, one Japanese, three enemy air forces. Only two other American pilots in the entire war will match that. But Kurds isn’t finished. 3 days later, he’s going to add a fourth flag to his scoreboard.

This one will be red, white, and blue. February 10th, 1945. Kurds leads a four- ship flight over the Formosa Strait. They find a Japanese airfield on Baton Island. Target of opportunity. The four Mustangs dive. Two Japanese fighters destroyed in the air. Three more burning on the ground. Lieutenant Lacro takes a direct hit. His engine dies. He puts it down in thePhilippine Sea, 300 yd from shore.

Kurds sends two pilots back to call for rescue. Then he goes to work. For 30 minutes, he strafes the Japanese positions. Every time someone moves toward the beach, he puts 50 caliber rounds in front of them. He’s burning fuel. He can’t spare, but nobody is capturing his wingman. Not while he’s still flying.

That’s when the C-47 appears. The C-47 took off from Lee 5 hours earlier. Routine flight to Manila. Should have been easy. Two hours in the air, they flew into a weather system that wasn’t on any forecast. A tropical depression spinning up from the south. Lightning first sheets of white fire outside the cockpit windows. Then turbulence.

The aircraft dropping 50 ft, slamming back up, dropping again. Passengers thrown against the ceiling. The pilot fought the controls, tried to climb above it, tried to descend below it. Nothing worked. Then the radio died. Electrical discharge. The equipment smoked, sparked, went silent. For two hours, they flew blind. No navigation, no communication, just a compass, a fuel gauge, and prayer.

When they broke clear, the fuel gauge was touching red. Nothing looked familiar. Nothing matched the charts. The pilot saw an island, an airfield. He didn’t question it. He had no way of knowing it was Japanese. Kurds sees the C-47 at 150 ft, seconds from touchdown. He tries the radio. Nothing. He dives in front of the transport, rocks his wings.

The C47 keeps descending. He fires a burst ahead of the nose. Tracer rounds lighting up the sky. The transport doesn’t waver. The Japanese gunners are shooting at Kurds now, protecting the C-47. They think it’s a captured prize. Kurds has run out of options. He knows what capture means. The Baton Death March.

75,000 soldiers forced to walk 65 miles. Anyone who fell was bayoneted. 10,000 dead in 6 days. The prison camps. 800 calories a day. Dysentery. Beatings. Executions. The massacres. 150 PS at Palawan herded into shelters and burned alive. Pilots beheaded with samurai swords. 12 people are about to experience that unless he stops them.

He swings behind the C-47, lines up on the left engine. This is the moment that will define his life. He pulls the trigger. The burst is surgical. 50 caliber rounds punch through the left engine. The propeller seizes. The C-47 keeps flying. One engine can keep it airborne. Kurds shifts aim, fires again. The right engine explodes.

The pilot banks toward the water. The C47 hits the Philippine Sea at 90 mph. The fuselage holds. Life rafts deploy. 12 survivors in the water. All alive. Lacroy paddles over. 13 people now. Kurds drops a note. For God’s sake, stay away from shore. Japs there. He circles until his fuel gauge touches empty.

Then he turns for home. Before dawn, Kurds is back. He leads a PBY Catalina to the crash site. Everyone accounted for, everyone alive. Two of the passengers are army nurses. One is named Svet Lana. Kurds had a date with her the night before. He’d had to cancel for the mission. Jeepers, he says.

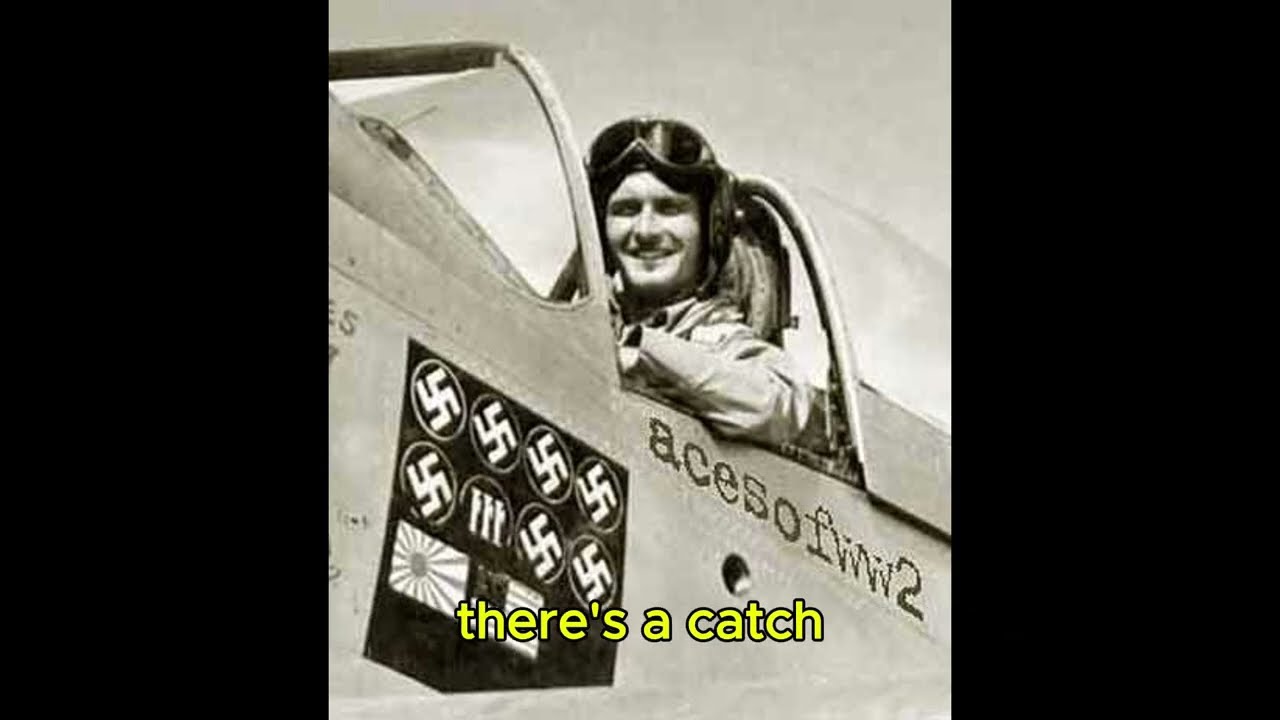

Seven 109s and one Mackey in North Africa, one and one Yank in the Pacific, and I have to go out and shoot down the girlfriend. General George Kenny commands Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific. An American pilot shot down an American plane, destroyed government property, and saved 12 lives. Kenny hands Kurds a medal, the air medal, for shooting down a friendly aircraft.

I told him I hoped he wouldn’t feel called on to repeat that performance. On the nose of Bad Angel, the ground crew adds a new kill marking, an American flag, four nations, four flags. No other pilot in World War II can make that claim. The girl in the life raft, Svetana Valeria Shostikovich Brownell, born in Harbin, Manuria, Russian immigrate family.

Her uncle was Dimmitri Shostikovich, the composer. Her stepfather was a US Marine. He brought the family to America before the Japanese invaded Manuria on February 10th, 1945. She ended up floating in the Philippine Sea because a pilot from Indiana shot her airplane down. According to Cur’s daughter, my dad might have been dating a nurse on the plane, but he went out on a blind date with my mom in Los Angeles.

The truth is somewhere in between. Here’s what’s not in dispute. April 13th, 1946, Allen County, Indiana. Louis Kurds marries Fetlana Brownell, 49 years, two children. A quiet life in Fort Wayne. Whatever happened in that life raft lasted half a century. After the war, Kurds stays in uniform. The Berlin Airlift, 1948-49.

He flies C-54 Sky Masters into Templehof. 277 days of roundthe-clock operations. 2.3 million tons of supplies. October 1963. Lieutenant Colonel Louie Kurds retires. 22 years of service. He starts a construction company. Builds houses instead of shooting down planes. February 5th, 1995. Fort Wayne. Louisie Kurds dies at 75.

They bury him at Lynenwood Cemetery. Nine aerial victories, four national flags, P escape, nine months behind enemy lines. Berlin Airlift veteran and the only American pilot ever decoratedfor shooting down an American plane. His widow Svetana dies October 2013 buried beside him. The math of February 10th, 1945.

12 Americans on that C47, zero survivors. if they’d landed. 12 survivors because a 25-year-old pilot made a choice no manual ever covered. Louis Kurds had 15 seconds. Shoot down a friendly plane or watch 12 people disappear into the Japanese prison system. He chose the trigger and then he married one of them.

That’s not a war story. That’s a love story. Strange and violent and impossible, but a love story all the same. Most heroes get statues, parades, their names on buildings. Louis Kurds got a flag on his airplane. Four flags: German, Italian, Japanese, American. The last one is the one that matters. The one nobody else has.

The one that says, “Sometimes the right choice looks exactly like the wrong one. Sometimes you have to shoot down your own people to save them. And sometimes, if you’re lucky, one of them becomes your