Archaeologists Found a Bigfoot Village Deep in the Rockies, Authorities Sealed It Off – Story

THE VALLEY THAT VANISHED

A letter sealed for an eighteenth birthday

Chapter 1 — For the Girl Who Still Believes in Hidden Doors

If you’re reading this, you’re eighteen now—old enough that the world has probably started trying to sand down the sharp edges of your curiosity. People will tell you that mystery is just ignorance wearing a costume, that magic is what children call coincidence, that every secret has already been mapped, measured, and sold. They will say it kindly, the way adults pass down disappointments disguised as wisdom.

.

.

.

I’m writing this because I promised myself one thing I never promised the government: that the truth wouldn’t die with me. I was sworn to secrecy decades ago about what my team found in the Rocky Mountains—about the valley the authorities sealed and then erased, about the beings who lived there, and about the price of bringing the outside world into a place that had survived precisely because it was forgotten. I kept my vow until now. Not because I feared prison. Not because the paperwork was binding. I kept it because I feared what people do to miracles once they decide the miracle belongs to them.

But you deserve to know. Not the tourist version. Not the polite lie about a “routine expedition” and “unusual rock art.” You deserve the whole story, the one that changed everything I thought I knew about intelligence, culture, and what it means to share a world with something older than our certainty.

It was the summer of 1987. Our team of four had been hiking for three days into a remote valley deep in the Rockies, sent to investigate reports of Indigenous cave paintings a ranger had stumbled across the previous year. The location was so isolated our supplies had to be dropped by helicopter every two weeks. No cell phones, and the radio barely worked in that terrain. We were cut off, which at the time felt like the purest form of fieldwork. Now, in hindsight, it feels like an omen: the valley was designed to keep outsiders out—and we marched into it anyway.

The place was breathtaking, the kind of landscape that makes you speak softer without knowing why. Pines towered like cathedral columns. Streams ran so clear they looked unreal. Mountains rose on all sides like fortress walls, holding the valley in a fist of stone and shadow. The air smelled sharp and clean—pine needles, wildflowers, cold water—and for the first few days we were simply happy, mapping and searching, assuming we were chasing history. We didn’t know we were about to meet a living present.

Chapter 2 — The Cave That Didn’t Paint Legends

On the fourth day we found the entrance, half-hidden behind a rockfall that looked recent, maybe from the previous winter. Clearing debris was slow work, a careful dance between patience and greed. We widened the gap enough to squeeze through and stepped into darkness that felt strangely lived in. Not just rock and damp, but something else—subtle, organic, like a room that had held breath.

Then our headlamps swept the walls, and I felt my stomach drop. The paintings weren’t like anything I’d seen in twenty years of archaeology. Most Native rock art I’d studied depicted animals, hunters, geometric motifs, the beautiful shorthand of a culture speaking to itself across time. These images were different: massive humanoid figures standing beside normal-sized humans, not as spirits or symbols, but as subjects—consistent proportions across multiple panels, scenes repeated with variations that suggested documentation rather than mythmaking.

It wasn’t a single “giant.” It was a pattern. A people.

We moved deeper and found more. Primitive shelters built from branches and mud. Tool marks on the walls. Carved implements scattered like someone had set them down and meant to return. But the scale was wrong in a way that made my skin prickle. The tools were sized for hands twice as large as ours. Sleeping platforms were enormous. Even the central fire pit in the main chamber was built for bodies that took up more space, that required more heat, more room.

And then came the detail that turned fascination into unease: signs of recent use. Ash that couldn’t have been older than a few weeks. Food remains piled in a corner—plant matter, bones of small animals, cracked in a way that suggested hands rather than jaws. Woven mats of grass and bark rolled against the wall as if stored. Everything whispered the same impossible conclusion.

Something intelligent was still using these caves. Something large.

We left before dusk, talking in clipped, rational fragments the way scientists do when they’re trying to keep wonder from becoming panic. We told ourselves it could be an unknown modern group using the caves. We told ourselves our eyes were interpreting scale incorrectly. We told ourselves anything that kept the world familiar.

That night, while the others slept, I lay awake listening to the valley’s quiet. It wasn’t silence—the Rockies are never truly silent—but it had a particular quality, like a presence held just beyond the edge of perception. The kind of quiet that isn’t empty, only careful.

At dawn I made a decision I’ve spent a lifetime questioning. I took my camera and binoculars and went back alone. I told myself it was for the light—soft morning illumination for photographing the art. The truth is I wanted to know whether my fear had a shape.

Chapter 3 — The Figure on the Far Slope

The trail to the cave took about twenty minutes, winding through mist and pine. Birds had just begun to sing, and for a while everything felt ordinary again—boots on dirt, camera tripod in hand, routine settling my nerves. I set up near the entrance and adjusted my lens.

That’s when I noticed movement across the valley, maybe half a mile away on the opposite slope. At first I thought bear—dark shape near the treeline. But it moved wrong for a bear. Too upright. Too deliberate.

I raised my binoculars and focused.

A creature stood at the forest edge in a clearing washed in pale dawn light, and for a moment my mind refused to accept what my eyes insisted on showing. It was bipedal, upright like a human, but far larger—eight or nine feet tall at least, covered in thick reddish-brown fur that caught the sunlight like copper. The hair was longer around the shoulders and head, giving it an almost manlike silhouette, but the body was built differently: broader chest, longer arms, a weight and balance that made each movement look controlled rather than clumsy.

What shook me most wasn’t its size. It was its purpose.

It wasn’t wandering. It was foraging. It moved through brush and stopped to examine certain plants with the concentration of a practiced gatherer. It selected specific stems, pulled them carefully, and placed them into what looked like a crude basket woven from bark. At one point it sat on a rock and sorted what it had gathered, separating some plants from others as if following a rule, a knowledge set, a tradition.

I watched for twenty minutes, frozen behind a boulder, afraid that the smallest movement would make me visible. The creature never looked my way. It didn’t have to. There was something about the valley itself that felt like a screen, a curtain drawn to protect what lived inside it.

When it finally disappeared into the treeline, I waited another ten minutes before I dared breathe like a normal person. Then I ran back to camp with the kind of urgency that makes you feel ridiculous and sane at the same time.

The others were eating breakfast. They looked up as I stumbled in, and I could tell by their faces they expected injury, not revelation. I sat down, tried to steady my hands, and told them what I’d seen.

There was skepticism, of course. There always is. But it didn’t last long, not after the paintings, not after the oversized tools, not after my description of purposeful gathering. We were already standing in the footprint of something that didn’t fit any comfortable category. All my report did was give the footprint a body.

Chapter 4 — The Hidden Bowl and the Village of Quiet People

The next morning I convinced one colleague to hike with me to the area where I’d seen the creature. We told the other two we were surveying the far side of the valley, which was true in the same way a locked door is “just wood.” We brought everything—telephoto lenses, notebooks, binoculars—because part of us understood that if we were wrong, we needed proof of our mistake. And if we were right, proof would become a different kind of danger.

The hike took hours through rough terrain. We scrambled over fallen trees and pushed through thick underbrush. Several times I worried I’d misjudged distance, that memory was playing tricks. But I’d marked the location on a topographic map and followed it like a lifeline.

Near midday we reached a ridge overlooking a hidden bowl—an inner valley within the larger one, a natural basin surrounded by steep cliffs on three sides. From our vantage point we had a perfect view down into the trees at the base of the cliff.

And there, nestled like a secret that had grown roots, was a settlement.

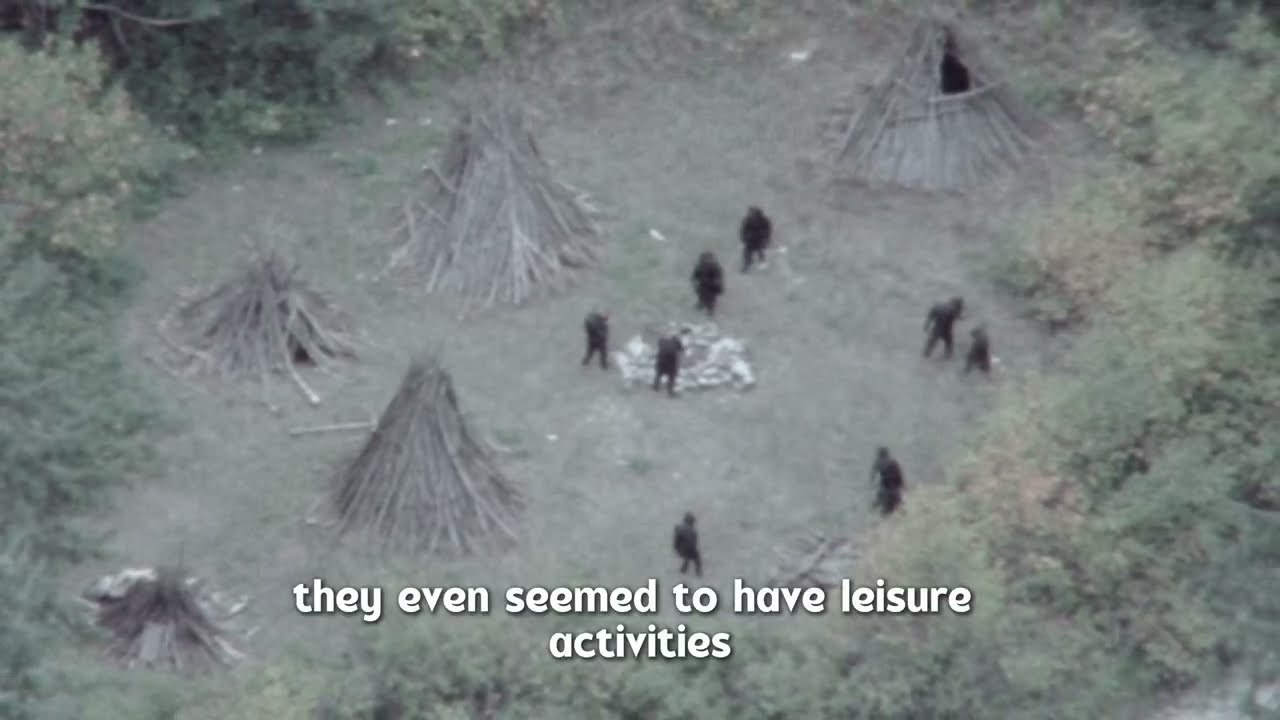

Not a random scatter of shelters. A village. Fifteen to twenty distinct structures built from woven branches, mud, and stone. Primitive materials, sophisticated design. Arranged in a rough circle around a central communal area with a large fire pit. Paths ran between the structures, worn smooth by years of use. Storage areas were built into the cliff face. A tool-making station sat in a shaded corner where figures moved with repetitive, skilled motions.

And the figures—God help me, those figures—were not one. They were many.

Big, furred, upright beings moved between structures as if this were the most natural thing in the world. Adults carried bundles of plants and firewood. Juveniles—smaller, faster—chased each other in games that looked like play, not hunting practice. Elders sat near entrances, watching with a calm that reminded me of grandparents in any human community.

My colleague and I stayed on that ridge all day, taking turns at the lenses, documenting everything we could without moving closer. We sketched the layout. We counted individuals when we could. Forty to fifty, we guessed, though the number shifted as they slipped in and out of structures and forest.

We watched morning gatherings around the fire pit that felt like meetings rather than accidents. We saw divisions of labor: groups leaving in different directions to forage, others staying behind to work. We saw instruction—young ones being shown how to weave, how to chip stone, how to carry without spilling.

The longer we watched, the harder it became to maintain the word “creature.” That word implies something beneath you, something you can categorize without consequence. What we were seeing looked like daily life—an intelligent society functioning without roads, without metal, without the need to announce itself to the world.

By late afternoon we were faced with an impossible decision. This was the discovery of the century, perhaps more: proof of a surviving intelligent hominid community in North America. Reporting it would rewrite textbooks and beliefs and laws. It would also bring the outside world crashing into that hidden bowl—hunters, journalists, scientists, politicians, opportunists, people who confuse discovery with ownership.

We talked on the ridge as the light began to fade, weighing responsibility against protection. In the end, the decision was made for us by practicality and fear: we had two other team members. We had an obligation to report, and we feared someone else might stumble into the village later without any chance of careful handling. We told ourselves that “proper channels” might mean protection.

We were naïve about what “proper” means when power gets involved.

Chapter 5 — Helicopters, Papers, and the Birth of a Cover Story

We told the other two that night, and their disbelief lasted exactly as long as it took to show the photographs and notes. Then the camp changed. Every small sound beyond the firelight felt loaded. Every shadow seemed to watch back. Not because the beings were threatening—our distance kept us safe—but because the truth has weight, and once you hold it, the world can’t feel the same.

We used our emergency radio to contact our base coordinator. The connection was terrible, full of static and dropped words, but we transmitted the essential facts: the cave art, the oversized implements, the settlement, the population, the evidence of culture. We begged for sensitivity. We asked for guidance.

What arrived within thirty-six hours wasn’t guidance. It was control.

Military helicopters appeared over the valley in a fleet. They landed near our camp, and men in uniform poured out alongside civilians with clipped haircuts and polite smiles. They identified themselves as federal officials, used language like “containment,” “security perimeter,” “protected area.” They asked hundreds of questions—where, how many, any direct contact—and then they began collecting our work. Photographs. Notes. Maps. Everything.

We were told to pack. We were being evacuated.

Before we boarded, they placed multiple documents in front of each of us. Non-disclosure agreements, written in language that felt less like a contract and more like a threat. The consequences for speaking were explicit. They used words like “national security,” as if an isolated community of hidden people could somehow endanger a nation more than the nation could endanger them.

They assured us it was for the beings’ protection. If word got out, the valley would be swarmed by hunters and thrill seekers and “experts.” The community would be destroyed. In that moment the logic sounded clean enough to accept. It was only later that I understood: the same reasoning that can protect can also imprison.

As the helicopter lifted off, I looked down and saw more aircraft arriving with equipment. A perimeter was being established. The valley was becoming a project.

Within the week we learned the public cover story: unexploded ordinance from old training exercises had been found in the area. Too dangerous for civilians. Off-limits. The region was quietly removed from public maps and official boundaries. To the outside world, the valley ceased to exist.

Two weeks after I returned home, a call came. A government liaison asked if I’d return as a civilian consultant. My expertise, they said, and my field observations made me valuable. The conditions were strict: military supervision, no independent documentation, no contact with anyone outside the operation about where I was or what I was doing. I would tell my family I was on an extended research expedition.

I said yes immediately. Not because I trusted them. Because I couldn’t bear the idea of that village being observed only through the eyes of people who saw it as a problem to manage. I told myself I could be a shield. I told myself the best way to protect those hidden lives was to be close enough to speak for them.

When I returned, the valley was unrecognizable. Temporary buildings clustered near our old campsite. Generators ran day and night. Camouflaged observation stations had been built on ridges overlooking the village, equipped with one-way glass and advanced optics. The fence line around the inner bowl was guarded and quiet. The operation’s stated objective was “minimal disturbance,” but the very existence of the fence was disturbance made physical.

For weeks I watched from those stations, logging behavior, mapping patterns, learning a communication system based on gesture, posture, and vocalization. The community gathered each morning around the central fire pit as if for a deliberate meeting. An elder—massive, silver-haired—appeared to lead it, using gestures the group responded to before dispersing. The division of labor was organized. The juveniles learned by doing, guided by patient adults. The elders were cared for. There were rules in their play. There was structure in their days.

And there was one female who kept looking toward the ridge as if she sensed the shape of being watched, even if she couldn’t see the watcher.

Chapter 6 — The Touch That Made Them Real, and the Token I Kept

Six weeks into the operation, everything nearly broke. A perimeter patrol got too close while checking fence lines and startled a large male foraging near the village edge. I heard frantic radio chatter, then saw it unfolding below: three armed soldiers, tense and uncertain, and one towering figure rising to full height and issuing sharp warning barks. The air between them tightened like a wire.

Then the figure charged.

It moved with terrifying speed, covering ground in a way that made human panic look slow. The soldiers raised weapons. In another few seconds someone would have died—either a soldier, or one of those beings, or both.

I did the only thing my ethics and my fear could agree on. I ran out of the observation post and downhill, waving my arms, throwing myself into the path. I dropped into a submissive crouch with my shoulders hunched and my eyes down, palms open. I made the low rumbling sound as best I could, more a desperate groan than anything authentic.

The being stopped ten feet from me. I could smell it—musk and pine and earth. I kept my gaze on the ground, my body saying what my mouth couldn’t: I’m not a threat. Don’t kill. Don’t die.

Slowly, I backed away, using gestures I’d observed. I hissed at the soldiers to lower their weapons and retreat. They argued in urgent whispers, but they listened—because there are moments when authority loses its voice and only survival speaks. The being watched us retreat, then turned back toward the forest. No one fired. No one fell.

After that, protocols changed. No armed personnel near the village without me present. And eventually, permission—reluctant, conditional—was granted for controlled contact attempts.

I began meeting the curious female at the forest edge, sitting with downcast eyes and open palms, offering dried fruit from rations. She approached cautiously, accepted, retreated. Over days the distance shrank. She began leaving gifts: woven grass, carved sticks with simple patterns, seed pods arranged as if selected for interest rather than utility. There was reciprocity—an understanding of exchange, an emerging relationship shaped by patience.

Two weeks in, she touched my hand. Enormous fingers, coarse hair, and yet the touch was gentle—curious, careful. She turned my palm over and traced the lines as if reading a map. In that moment, the boundary between myth and reality shattered. No matter what anyone called her species, no matter what paperwork said, she was a person in the only way that matters: she made choices, she communicated intent, she offered trust.

Soon after, she beckoned me into the village. The silver-haired elder approached, examined me with a firm hand on my head, then made a decisive gesture—permission. I walked through the clearing under dozens of watching eyes, trying to keep my posture humble, feeling the weight of what I was being allowed to do. I saw their rituals. I saw a grove marked with carved symbols and woven objects hung like offerings. I saw stones arranged in patterns that served no practical purpose. I was shown a burial ground—graves marked with stones facing the rising sun. That revelation broke something open in me. These beings honored their dead. They remembered. They had a relationship with time.

And then the operation shifted. The military’s mood changed from curiosity to anxiety. Restrictions tightened. Tracking devices. Limited visits. Talk—quiet, bureaucratic—of relocation to a controlled facility where “research could be standardized.” The idea horrified me. Remove them from ancestral land, from graves, from sacred caves, and you wouldn’t be “studying” them. You’d be destroying them.

Two days after my final village visit, I was told the operation was “terminated.” I was evacuated. I was debriefed for hours, questions framed like intelligence gathering—capabilities, vulnerabilities, routines. New documents were placed in front of me with harsher consequences. The valley would remain classified. I would never speak.

I never learned what they did next. Whether they left the community alone under permanent containment. Whether they relocated them. Whether the village still exists at all. The valley was erased from maps so thoroughly that even searching for it would raise alarms.

I returned to my career and lived a normal life on the outside, but something in me never came back from that bowl of trees and cliffs. I carried one piece of proof with me, not a photograph—those were taken—but a small carved token the female left one morning: wood etched with simple symbols, smoothed by hands that weren’t human but were undeniably deliberate. I kept it hidden for decades, not because I feared punishment, but because I feared what proof would do in the wrong hands.

Now, I’m old. You’re eighteen. And I want you to know the world is still wide enough for wonder. There are truths that never make it into textbooks because they’re inconvenient to the powerful or dangerous to the fragile. There are places that vanish not because they aren’t real, but because someone decided reality needed to be managed.

If you tell anyone, do it with care. If you go looking, don’t. Not because you’re incapable, but because the greatest protection some lives have is the world’s disbelief.

Keep this letter safe. Keep your mind open. And remember: sometimes the most ethical form of discovery is not to reveal, but to respect.