A few hundred Australians against 5,000 Chinese soldiers. The odds 1 to 10. A vertical assault on a fortress that the Americans couldn’t even scratch. Command had already written them off as quote zero. But these BS didn’t just survive. They did the impossible. And then their victory was taken away with the stroke of a pen without a single shot fired.

This is the story of the greatest infantry feat Australia performed in the 20th century. A story you were never told because someone wanted you to forget. Today you’ll learn how a handful of diggers became ghosts, climbed through the fog, and seized the eagle’s nest. How one sergeant held his position for 6 hours against waves of Chinese infantry with seven bayonet wounds in his body.

and why 47 years later he shook hands with the man who tried to kill him that night. But most importantly, you’ll find out who gave away the hill soaked in Australian blood and why. Watch until the end because the finale of this story is something you definitely won’t expect. The Korean War, a conflict wedged between two giants of memory.

The global triumph of World War II and the psychological wound of Vietnam. Historians call it the forgotten war. And this title is not poetic exaggeration. This war truly fell out of public consciousness. Too small to compete with the scale of the Second World War. Too early to become a television sensation like Vietnam.

It simply got lost between epics. Although it claimed over 3 million lives. By autumn of 1951, the front lines in Korea had frozen. The sweeping offensives and dramatic breakthroughs of the first year gave way to something grimly familiar. trench warfare, static positions, a grinding meat grinder where every hill, every ridge, every nameless height became a miniature Verdun.

Soldiers on both sides dug into the frozen earth and waited for orders, for artillery, for the whistle signaling another futile assault. But here’s the thing. In this forgotten war on this frozen peninsula, Australian soldiers were about to perform something extraordinary. something that militarymies would study for decades.

Something that should have made headlines around the world but instead vanished into the fog of political convenience. And the most bitter part, almost no one remembers it happened. What you are about to hear is not just another war story. This is the tale of a few hundred men who defied mathematics, physics, and common sense to achieve what entire divisions could not, and then watched helplessly as their triumph was erased by bureaucrats who had never heard a shot fired in anger.

Rising sharply above the jagged Korean landscape stood a mountain the locals called Marangan. The Allied forces knew it simply as Hill 317. But those who had tried to take it called it something else entirely, the Eagle’s Nest. And like any eagle’s Nest, it sat at a height where only the bold or the foolish dared to climb.

This was not just another hill on a military map. Marangan was a natural fortress of granite and ice, dominating the entire valley below like a stone sentinel. Whoever controlled that summit controlled everything. supply routes, observation lines, artillery positioning. From the top, you could see Allied movements for miles in every direction, every truck convoy, every troop rotation, every ammunition delivery.

The Chinese knew exactly what they possessed, and they had turned this geographic gift into something truly terrifying. The Chinese people’s volunteer army had spent months transforming Marangan into a vertical killing machine. Deep bunkers carved into the reverse slopes, invisible to Allied bombers. A honeycomb network of interconnected tunnels allowing defenders to appear, disappear, and reappear at will.

Heavy machine gun nests positioned to create interlocking fields of fire, meaning every square meter of approach was covered by multiple weapons simultaneously. Mortar positions zeroed in on every possible climbing route. The slopes themselves had become a graveyard of previous ambitions. American units had already tried and failed, leaving behind shattered equipment and bitter lessons.

For any conventional military force, Marangan was an objective to be bypassed or bombed into rubble, never taken by infantry assault. The mathematics simply did not work. Attacking uphill against entrenched defenders violates every principle of warfare. Yet, someone at Allied command had decided this fortress must fall.

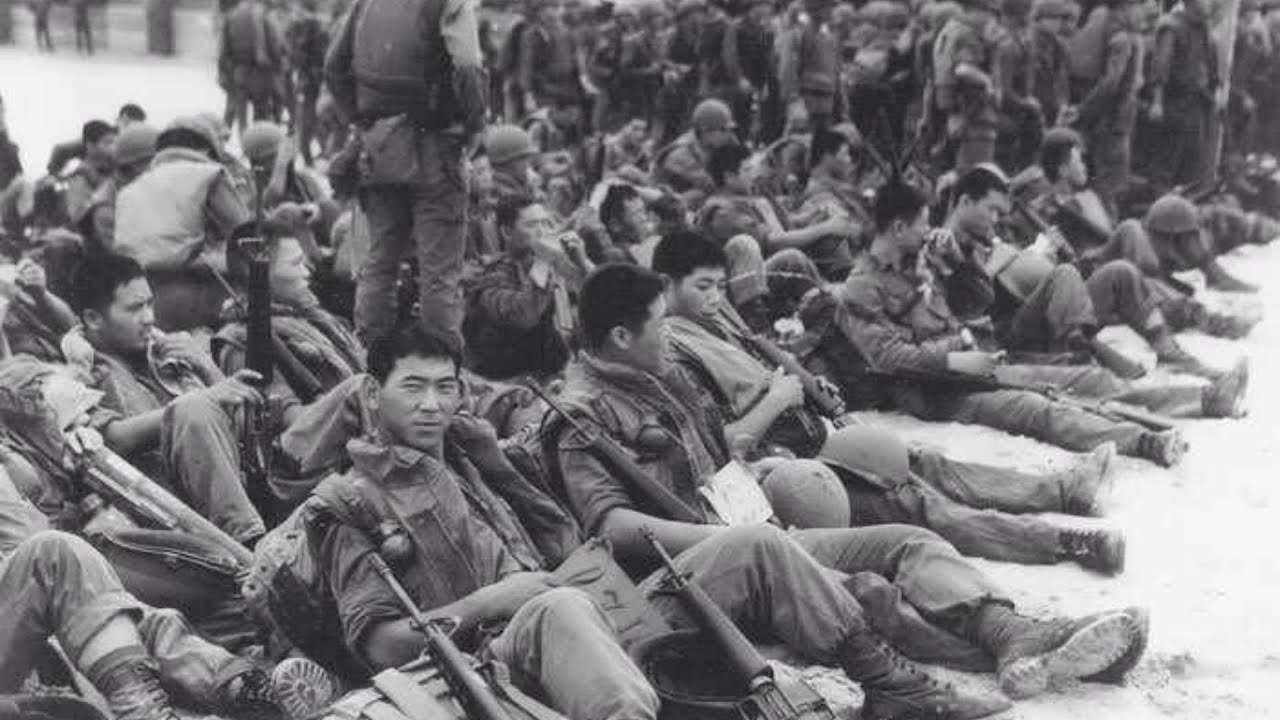

And the men chosen for this impossible task were about to receive orders that looked suspiciously like a sentence. The third battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment, known simply as 3 R, received their orders in early October of 1951. The mission brief was straightforward in its wording, but staggering in its implications. Capture Marangan through direct infantry assault.

No elaborate flanking maneuvers, no month-long siege, just Australian boots climbing toward Chinese guns. These were not green recruits being sent into the meat grinder. The men of three R were veteran diggers who had already proven themselves at the Battle of Capyong earlier that year, where they had held off waves of Chinese attackers against similarly absurd odds.

They knew exactly what they were being asked to do. They understood that American units with superior numbers and heavier equipment had already broken themselves against these same granite slopes. The previous attempts had not even reached the secondary ridges before being thrown back in bloody confusion. At Allied headquarters, the prevailing attitude toward this operation was grimly pragmatic.

Marangan needed to fall to straighten the front line. And if a battalion of Australians had to be sacrificed to achieve this, well, that was an acceptable cost of war. The generals drew their arrows on maps and calculated casualty percentages with clinical detachment. They expected heavy losses. Some privately doubted any meaningful success was possible at all.

But the generals had not counted on one critical factor. Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hasset. The commanding officer of three RAR was no parade ground soldier content to follow suicidal orders blindly. Hasset was a tactical innovator, a man who looked at impossible problems and saw unconventional solutions.

While his superiors prepared condolence letters in advance, Hasset was preparing something else entirely. He had no intention of marching his men into a frontal slaughter. He was going to make them vanish into thin air. And when they reappeared, it would be exactly where the enemy least expected. Now, let us talk numbers because the mathematics of this mission bordered on institutional insanity.

The third battalion Royal Australian Regiment fielded roughly 600 men for the assault. Waiting for them on the heights of Marangan was a Chinese force of divisional strength. Approximately 5,000 veteran soldiers. Do the calculation yourself. One Australian for every 10 Chinese defenders. One man climbing upward for every 10 men shooting downward from prepared positions.

Military doctrine has a term for this kind of ratio. It calls it unwinable. Every textbook, every war college lecture, every tactical manual states the same principle. Attacking forces need a minimum 3 to1 numerical advantage against entrenched defenders. The Australians had the inverse. They were outnumbered 10 to1 attacking uphill against fortified bunkers with no element of surprise.

At least that was the assumption. But the numbers only told part of the horror story. The environment itself seemed designed to end Australian lives. Late October in the Korean highlands brought a bone penetrating cold that turned sweat into ice inside uniforms. The mountain was perpetually draped in thick wet fog, a clammy white shroud that reduced visibility to mere meters.

Soldiers began calling it the white zone, and for good reason. In that fog, an enemy could be standing close enough to touch before you even saw a shadow. The rocky trails turned into treacherous slides of frozen mud where one wrong step meant tumbling down cliffs or sliding directly into Chinese firing positions.

The defenders knew every rock, every crevice, every approach route. They had mapped the entire mountain for their mortars and machine guns. They sat in warm bunkers drinking tea while the Australians would have to crawl through freezing mist, exhausted, exposed, and vastly outnumbered. On paper, this was not a battle. This was an execution with extra steps.

Yet, sometimes the most dangerous thing an army can do is tell Australian soldiers that something cannot be done. The night of October 4th, 1951, a cold darkness had settled over the Australian positions at the base of Marangan. Tomorrow, at dawn, these men would begin climbing toward what most assumed would be their final destination.

But tonight, in shallow foxholes and improvised shelters, a different kind of ritual was taking place. The soldiers were writing letters home. Some wrote to wives waiting anxiously in Brisbane or Sydney. Women who had already survived years of worry during the Second World War, and now faced that familiar dread once again.

Others wrote to mothers who had kissed them goodbye at train stations, trying to hide tears behind forced smiles. A few wrote to children they had never met. Babies born while their fathers were shipped halfway around the world to fight in a country most Australians could not find on a map. The scratching of pencils on paper was the only sound competing with the distant rumble of artillery.

Corporal Tommy Ryan from Brisbane sat hunched over a crumpled sheet composing words for his pregnant wife back home. She was expecting their first child in December, and Ryan had already accepted he might never see that baby’s face. His letter contained a simple request that spoke volumes about the faith these men placed in their commander.

If he did not return, she should name the child Frank after Lieutenant Colonel Hasset. He was the only officer who genuinely seemed to believe the battalion would survive the morning. In a situation where hope was scarce, that belief meant everything. When the letters were finished, the soldiers folded them carefully into waterproof pouches and handed them to the medical orderlys.

This was standard procedure before major assaults, though no one liked to speak its purpose aloud. If the writers did not return, these pouches would travel home in their place. Some letters would reach their destinations weeks later, delivered to doorsteps where gold stars would soon hang in windows. Others would be reclaimed by their authors after the battle, tucked away as souvenirs of a night when tomorrow seemed like a foreign country.

But first, these men had a mountain to climb. While his men wrote their final letters, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hasset was studying maps and weather reports by candlelight. He had no intention of throwing Australian lives away in a conventional frontal assault. The Chinese expected a textbook attack.

Infantry advancing up the main approaches, easy targets for interlocking machine gun fire. Hasset planned to give them something entirely different. He would turn the enemy’s greatest defensive asset into their fatal blind spot. The key to his plan was that perpetual blanket of fog, the very same white zone that made Marangan so terrifying.

The Chinese relied on that mist to conceal their bunker positions and disorient attackers. But fog works both ways. If you cannot see the enemy, the enemy cannot see you. Hasset realized that the thickest fog accumulated along the eastern and northern ridges, slopes so steep and treacherous that Chinese commanders had deemed them physically unclimbable.

No sane military force would attempt those routes. So the defenders had placed minimal centuries there. And that was precisely where the Australians would go. The operational philosophy was brutally simple. Strike fast, dig in deep, hold tight. The battalion would scale the impossible cliffs under cover of darkness and fog, bypassing the heavily defended main approaches entirely.

They would move like ghosts, silent and invisible, climbing routes that existed only on the most detailed topographical surveys. By the time the Chinese realized what was happening, Australian soldiers would already be above them, looking down into positions designed to repel attacks from below. Coordinating this audacious scheme required precise artillery support.

Hasset worked closely with the New Zealand 16th Field Regiment, planning a creeping barrage that would pin Chinese defenders inside their bunkers at exactly the right moments. The shells would march up the mountain just ahead of the climbing infantry, forcing the enemy to keep their heads down while Australians crawled past observation posts mere meters away.

One miscalculation, one poorly timed salvo, and the barrage would fall on Australian heads instead. The margin for error was essentially zero. But Hasset trusted his Kiwi gunners and they would not let him down. October 5th, 1951, 3:30 in the morning. The fog was so thick it felt like breathing underwater. Somewhere above, invisible in the white darkness, waited 5,000 Chinese soldiers with orders to hold the mountain at all costs.

And at the base of the cliffs, 600 Australians began to climb. They moved in absolute silence, each man acutely aware that a single dropped rifle, a single loose rock, a single cough could bring devastation down upon them all. The diggers had wrapped their equipment in cloth to prevent metal clinking against metal. They communicated through hand signals, touch, and instinct.

The only sounds were the soft scrape of boots against granite, the muffled breathing of men hauling themselves upward, and their own heartbeats pounding in their ears. Somewhere in the fog ahead, Chinese sentries stared blindly into the white void, seeing nothing. The New Zealand artillery opened up precisely on schedule, shells screaming overhead to crash into the main Chinese defensive positions.

The barrage was deliberately designed to sound like preparation for a conventional assault on the primary approaches. Inside their bunkers, Chinese defenders braced for the expected infantry wave from the south and west. They had no idea that Australian soldiers were already scaling the unguarded cliffs directly above them, passing within meters of outposts whose occupants were deafened by explosions and blinded by fog.

The audacity was breathtaking. One company literally crawled past a machine gun nest close enough to hear the crew talking inside. As the first gray light of dawn began filtering through the mist, something impossible happened. Chinese lookouts on the forward ridges rubbed their eyes in disbelief. Emerging from the precipaces they had dismissed as unclimbable, materializing like apparitions from the white void came Australian slouch hats.

Dozens of them, then hundreds. The ghosts had arrived at the doorstep of the fortress, and they had brought bayonets. The moment the sun began burning through the fog, all tactical elegance evaporated. What replaced it was something far more primal. Close quarters butchery on a scale that defies comfortable description.

The Chinese, recovering from their initial shock, unleashed the full fury of a 5,000 strong garrison. Every bunker spat fire. Every trench became a killing ground. Marangan transformed from a tactical objective into a meat grinder where men fought and perished at arms length. The trenches were too narrow for rifles to be effective.

Soldiers resorted to bayonets, grenades, entrenching tools, and bare fists. Australians stormed bunker after bunker, clearing each one in savage hand-to-hand struggles, where victory meant being the last man standing in a concrete room full of bodies. The Chinese launched counterattack after counterattack, human waves crashing against Australian positions with fanatical determination.

Each assault was beaten back, but each assault cost more lives, more ammunition, more of that precious reserve of human endurance that every soldier carries into battle. For 5 days and five nights, the men of three R existed in a waking nightmare. They did not sleep because sleep meant a Chinese grenade rolling into your foxhole.

They barely ate, surviving on whatever rations they could stuff into pockets between firefights. The cold was merciless. Sweat from exertion froze inside uniforms, turning fabric into icy armor that chafed skin raw. Hands cracked and bled from digging fighting positions in frozen earth while mortar rounds exploded meters away.

Men who had climbed the mountain as soldiers were being forged into something harder, something that operated beyond normal human limits. Between the waves of Chinese attacks, the Australians performed their own miracles of endurance. They dragged wounded comrades down the same vertical cliffs they had scaled, often under direct fire.

They shared their last scraps of food and their final magazines with mates whose supplies had run dry. They huddled together in shallow scrapes for warmth. Trembling uncontrollably, listening to the whistle of incoming shells, and somehow finding the will to stand up and fight again when the next assault came. Brotherhood was not an abstract concept on Marangan.

It was the only thing keeping men alive. The third night of fighting brought the Chinese their closest chance at breaking the Australian lines. Under cover of darkness, a massed assault punched through the battalion’s left flank, threatening to roll up the entire position. In the chaos and confusion, one machine gun nest found itself completely isolated.

The crew had been hit, some carried away by stretcherbearers, others lying motionless in the frozen mud. Only one man remained behind the weapon. Sergeant Duncan McGregor, 34 years old, a cattle farmer from Queensland who had traded the red dust of the outback for the frozen granite of Korea. For 6 hours, McGregor held that position alone.

Wave after wave of Chinese infantry came screaming out of the darkness, and wave after wave broke against his single chattering machine gun. He fired until the barrel glowed red. He cleared jams with fingers so cold they could barely feel the metal. When the ammunition belts finally ran dry, he grabbed the weapon by its scorching barrel and used it as a club.

The mathematics were absurd. One exhausted man against hundreds of determined attackers. But McGregor was not doing mathematics. He was simply refusing to let the enemy pass. When Dawn finally arrived and Australian reinforcements fought their way to the position, they found a scene that would haunt them for decades.

McGregor was still there, slumped against the sandbags, barely conscious. His body bore seven bayonet wounds. The machine gun lay beside him, its stock shattered from impacts against bone and helmet. Scattered around the position were the bodies of 23 Chinese soldiers who had tried to take that single nest and failed.

The sergeant had held his ground through an entire night of hell, armed with nothing but willpower and a broken weapon. McGregor survived his wounds and eventually returned to his cattle farm in Queensland. He lived another 41 years, raised a family, and became a respected figure in his community. But he never spoke about that night on Marangan.

Not to his wife, not to his children, not to the journalists who occasionally came looking for war stories. Some experiences are too heavy to share, and some silences speak louder than any words. The men who served beside him understood. They never pressed him to talk. They simply knew what kind of man had stood in that trench when the darkness came.

October 8th, 1951. Morning light broke over Marangan to reveal something that Allied command had privately considered impossible. Australian soldiers stood on the summit of Hill 317. The eagle’s nest had fallen. The Chinese divisional flag that had flown defiantly over the peak was gone, replaced by exhausted diggers staring out across the valleys they had conquered through 5 days of unrelenting combat.

The numbers told a story that made staff officers reach for their calculators in disbelief. A single battalion of fewer than 600 Australians had systematically dismantled and driven out a force of nearly 5,000 entrenched Chinese veterans. They had attacked uphill against fortified positions with a 10 to1 numerical disadvantage and won. They had done what whole American divisions had attempted and failed to accomplish in the months prior.

The Chinese divisional command was in chaotic retreat, abandoning a position they had sworn to hold to the last man. The strategic observation post that had dominated the entire sector now belonged to the allies. When reports reached headquarters, the initial reaction was stunned silence, followed by frank incredility.

Generals who had written off the assault as a necessary sacrifice now scrambled to understand how their throwaway battalion had achieved the impossible. Military analysts would later describe the capture of Marangan as the greatest single infantry feat performed by Australian arms in the 20th century. This was not hyperbole or patriotic exaggeration.

It was a sober, professional assessment of an achievement that defied conventional military logic. Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hasset’s masterpiece of artillery coordination, tactical deception, and raw infantry grit had worked beyond anyone’s expectations. The men who stood on that summit were not the same men who had written letters home four nights earlier.

They were something forged in fire, bonded by shared suffering, transformed by an experience that would mark them forever. They had conquered the mountain. They had beaten the odds. They had proven that courage combined with cunning could overcome any obstacle. But their triumph was about to be betrayed in a way none of them could have imagined.

Less than one month later, the men who had bled for Marangan received orders that hit harder than any Chinese mortar shell. They were commanded to withdraw, not because the enemy had driven them back. Not because the position had become untenable, but because diplomats in distant tents had decided to redraw lines on a map.

The peace negotiations at Panunjam were grinding forward in their slow bureaucratic dance. Allied commanders wanted a straighter, more defensible front line. Marangan, jutting forward as a salient, required too many resources to hold in a static war of attrition. The generals looked at their maps, calculated logistics, and decided that this particular piece of blood soaked granite was expendable.

With a few signatures and radio transmissions, the order went out. Abandon the heights. pull back to new positions, surrender the eagle’s nest without a fight. For the veterans of three R, the withdrawal was an exercise in controlled heartbreak. They packed their gear in bitter silence and began the long march down the same cliffs they had scaled through fog and fire.

Every step felt like betrayal. Every meter descended was a meter of sacrifice rendered meaningless. They had watched friends fall on these slopes. They had dragged wounded comrades across this frozen rock. They had held this ground through 5 days of hell against 10 to one odds. And now they were simply walking away because politicians had decided their victory was inconvenient.

The crulest moment came when they reached the valley floor and looked back up at the summit. Chinese soldiers were already returning to Marangan, reclaiming the fortress without firing a single shot. The same position that had cost so much Australian blood was being handed back on a silver platter of diplomatic compromise.

Within hours, Chinese flags flew once again over Hill 317. The eagle’s nest had changed hands, not through combat, but through paperwork. For the men watching from below, something fundamental broke that day. They had learned the hardest lesson of modern warfare, that a soldier’s sacrifice means nothing when weighed against a diplomat’s agenda.

Here is the bitter irony that makes Marang son such a painful chapter in military history. This battle should have been front page news across the Western world. A few hundred men defeating 5,000 against impossible odds. That is the stuff of Hollywood films and national mythology. Instead, the triumph of three R vanished into historical obscurity almost before the gunsmoke cleared.

The question is why? The answer lies in timing and the cruel mathematics of media attention. In October of 1951, the global press was fixated on the peace negotiations at Panunjam and the larger chess game of cold war politics. Editors wanted stories about diplomatic breakthroughs, superpower confrontations, and the looming threat of nuclear escalation.

A battalion of Australians capturing a hill in Korea simply could not compete for column inches. The story was buried beneath headlines about truce talks and political maneuvering, reduced to a paragraph or two in newspapers that would be used to wrap fish the following day.

There were no victory parades when the soldiers returned home. No ticker tape celebrations through Sydney streets. No politicians lining up to shake hands and claim reflected glory. The men of three R came back quietly, absorbed back into civilian life without fanfare or recognition. Most Australians had no idea what had been accomplished in their name on that frozen Korean mountain.

The greatest infantry feat of the century had been performed in silence and would remain in silence for decades. Militarymies around the world would eventually study Marangan as a textbook example of tactical brilliance. Staff officers from a dozen nations would analyze Hasset’s fog infiltration and artillery coordination.

The battle became required reading at the Australian Command and Staff College, taught as the gold standard for battalion level assault on fortified positions. Yet the average citizen has never heard of it. The men who fought there received their recognition from professional soldiers who understood what they had achieved and from no one else. Perhaps that was fitting.

The diggers of three R had never sought fame. They had simply done their job and expected nothing in return. But they deserved better than to be forgotten. What kind of men could achieve what three R accomplished on Marang son? The answer reveals something fundamental about Australian military culture, something that sets the digger apart from soldiers of other nations.

These were not warriors who sought glory or dreamed of medals. They were professionals defined by quiet excellence. Men who measured success not in headlines but in objectives secured and mates brought home alive. The Australian digger has never been about flashy heroics or theatrical bravery. The ethos runs deeper and harder than that.

It is about grim endurance when every muscle screams for rest. It is about maintaining discipline when chaos swirls and lesser units would fracture. It is about the corporal who sees an opportunity and seizes it without waiting for orders from above. On Marangan, this culture of initiative proved decisive. When fog obscured the battlefield and communications broke down, individual section leaders made critical decisions that kept the advance moving.

They did not freeze waiting for instructions. They adapted, improvised, and overcame. The unglamorous work mattered just as much as the bayonet charges. Digging fighting positions in frozen earth while mortar rounds exploded nearby. Hauling ammunition up vertical cliffs on bleeding hands. Stripping and cleaning weapons in the pre-dawn darkness so they would function when lives depended on them.

The diggers performed these exhausting tasks with the same dedication they brought to combat. They understood that battles are won not just in moments of violent contact, but in the countless hours of preparation and maintenance that make those moments possible. Marangan became a template for future Australian military doctrine.

The principles demonstrated there small unit initiative, aggressive patrolling, integration of fire and movement, psychological resilience under extreme conditions would form the foundation of Australian special operations for generations to come. When the Special Air Service Regiment was established and expanded, its instructors looked back to battles like Marangan for lessons in what determined men could achieve against overwhelming odds.

The diggers of three R never knew they were writing a manual for elite warfare. They were simply doing what Australians do, getting the job done without complaint and without fanfare. 1998, Sydney, Australia. A veterans conference brought together old soldiers from conflicts spanning half a century. Among the attendees was a 79-year-old former sergeant named Duncan McGregor, the Queensland farmer who had held a machine gun position alone through that terrible third night on Marang Sunan.

47 years had passed since those six hours of hell. His wounds had healed into faded scars. His nightmares had mostly stopped, but some memories never fully released their grip. Across the conference hall sat another elderly man, Chen Wuo, 76 years old, a former platoon commander in the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army.

Through the strange channels of postwar reconciliation, former enemies had been invited to share their experiences. Chen had commanded one of the assault waves that crashed against Australian positions on that frozen October night in 1951. He had sent men forward into the darkness toward a single chattering machine gun that simply would not fall silent.

For decades, the mystery of that position had haunted him. Through a translator, the two old soldiers finally spoke. Chen leaned forward with a question that had burned in his mind for nearly five decades. His unit had been convinced they were attacking a full company position, perhaps 40 or 50 men with multiple weapons.

the volume of fire, the sustained resistance, the sheer impossibility of breaking through. It had to be a major defensive installation. When McGregor quietly explained that he had been alone behind that gun, Chen sat back in stunned silence. One man, one weapon against three full assault waves. McGregor’s response was simple and carried no boast.

He could not stop firing because his mates were depending on him. The men behind that position, sleeping in exhausted heaps between attacks, were counting on the gun staying in action. Stopping was not an option. The two veterans looked at each other across the table. Former enemies now just two old men carrying the same weight of memory.

They shook hands while a photographer captured the moment. In that image, their eyes told identical stories. These were men who had seen the worst humanity could do and somehow survived to sit in a conference room discussing it over tea. War makes enemies of strangers, but time sometimes makes brothers of enemies. The physical heights of Marangan were eventually surrendered to political compromise.

But the lessons written in blood on those granite slopes would reshape military thinking for generations. What happened on Hill 317 did not merely add another battle honor to regimental colors. It fundamentally rewrote the manual on what determined infantry could achieve against impossible odds. The primary tactical legacy was the perfection of coordinated fire and movement under extreme conditions.

Lieutenant Colonel Hasset’s synchronization of New Zealand artillery with climbing infantry became a case study in how technology and firepower must serve the soldier on the ground, not the other way around. Staff colleges across the Western world analyzed how a creeping barrage could be timed so precisely that men could crawl within meters of enemy positions while shells exploded just ahead.

The integration was so seamless that Chinese defenders never understood they were being bypassed until Australian bayonets appeared in their trenches. More profound was the proof that numerical disadvantage could be overcome through superior tactics, terrain exploitation, and sheer fighting spirit.

Military theorists call this the force multiplier effect, the ability of well-trained troops to punch far above their weight class. Marang son became the gold standard example. When officers at the Australian Command and Staff College teach battalion level assault on fortified positions, they teach Marangan. When analysts study how to turn environmental obstacles into tactical advantages, they study Hasset’s fog infiltration.

The battle demonstrated that the human element remains decisive even in an age of mechanized warfare. The phrase that emerged from the campaign, “When the mountain is high, do not turn back,” transcended mere slogan status. It became operational doctrine, a reminder that obstacles exist to be overcome, and that the most dangerous enemy is the voice suggesting retreat.

Every Australian soldier who has served in the decades since inherits something from those frozen ridges. The men of three RA prove that courage combined with cunning creates its own mathematics where one determined digger can equal 10 uncertain defenders. That lesson remains as relevant today as it was in October of 1951.

The Chinese reclaimed the summit of Marangan in November of 1951. Their flags flew once again over Hill 317 and the strategic observation post returned to enemy hands. On paper, it appeared as though the sacrifice had been erased. The victory rendered meaningless by the cold equations of diplomacy. But there are things that paperwork cannot undo.

And there are heights that transcend mere geography. The Australians who fought on that mountain occupied something far more permanent than a granite peak. They claimed the moral high ground in a way that no treaty negotiation could ever surrender. A hill can be given away by generals who never climbed it. A position can be abandoned by politicians who never bled for it.

But the honor of having taken that hill against 10 to1 odds, of having done what every expert declared impossible, that belongs to the soldiers forever. No signature can transfer it. No diplomatic compromise can diminish it. The glory of Marangan lives in a place beyond the reach of bureaucrats. Today at the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Busousan, South Korea, rows of white headstones mark the final resting places of those who did not descend from the mountain.

Their names are carved in stone. Young men from Brisbane and Sydney, from Melbourne and Perth, from cattle stations in Queensland and fishing villages in Tasmania. They came halfway around the world to fight in a forgotten war. And they remain there still, keeping eternal watch over a peninsula most of their countrymen will never visit.

Official monuments honor their sacrifice in granite and bronze, but the true memorial exists in a different form. Local villagers near Marangan speak of something strange that happens every October when the fog rolls thick across the ridges and the pre-dawn darkness mirrors those mornings of 1951. They say you can hear footsteps in the mist, the sound of boots on granite climbing ever upward.

The soft clink of equipment and the heavy breathing of men defying gravity. The ghosts of three R are still ascending, still pushing toward a summit that awaits them in eternity. They are the phantoms in the fog, forever climbing, forever faithful. A hill can be given away. The honor of having taken it can never be stolen.