With all due respect, sir, we’ve been doing this for 6 years. We don’t need a lecture on wind reading from a civilian. The words cut through the desert air at the 29 Palms Scout Sniper Range, spoken by a Marine sergeant whose confidence far exceeded his current performance. For 3 hours, an elite four-man sniper team had been attempting to engage a target at 2,000 yards.

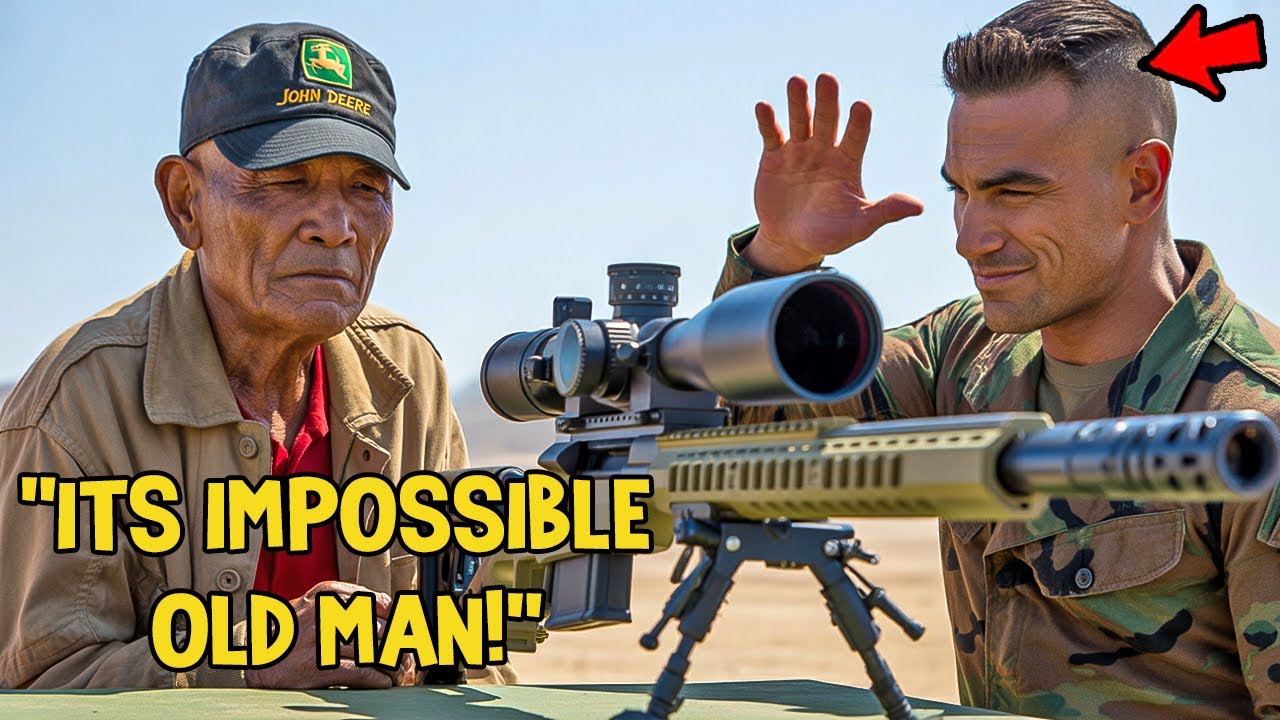

and for 3 hours every single round had missed. The old man standing behind the firing line in his faded jacket and John Deere cap had quietly suggested they were underestimating the wind value and ignoring the corololis effect at extreme range. They’d laughed politely, but they’d laughed. Then he took the rifle, made two small adjustments, and sent a round through dead center of the target on his first shot.

If you believe experience deserves respect regardless of appearance, type honor in the comments. His name was Robert Chen, though everyone who’d known him in his previous life called him Ghost. At 71 years old, Robert lived alone in a small house in Yucka Valley about 40 minutes from the marine base. His days followed a careful routine.

Morning coffee on the porch, watching the desert sunrise. Afternoons reading or tinkering with old rifles in his garage workshop. Evening so quiet you could hear the wind move through the Joshua trees. He’d been a widowerower for 6 years, and his two daughters lived on the east coast with families of their own.

They called on Sundays. He told them he was fine, and mostly he meant it. The only time Robert really felt alive anymore was when he came to the base. Not often, maybe once every few months, but when the loneliness got too heavy or the silence too oppressive, he’d drive to 29 Palms and park near the public areas where you could hear the ranges, where the sound of rifle fire connected him to the person he used to be.

Nobody recognized him. Why would they? He’d retired in 2003, and the Marine Corps had cycled through entire generations since then. He was just another old veteran trying to maintain some connection to a life that had moved on. The morning of October 14th, Robert had driven to the base on impulse. The desert was particularly beautiful that day, the kind of crisp autumn morning where the air was so clear you felt like you could see forever.

He’d parked near the scout sniper range complex, a secure facility where the core trained its precision marksmen. You weren’t supposed to be able to see the ranges from the public area, but Robert knew all the spots where the topography allowed you to observe from a distance. Old Habits. That’s when he noticed something unusual. At the 2,000yard range, a position he’d spent countless hours at during his career, there was a sniper team that appeared to be struggling badly.

Through his old Leica binoculars, Robert could see four Marines at the firing point with what looked like two instructors and a senior officer observing. The shooter would fire, everyone would check through spotting scopes, heads would shake, and they’d reset for another attempt. This pattern continued for over an hour.

Robert’s professional curiosity overwhelmed his usual caution. He’d started walking closer, using the access road that maintenance vehicles used, technically off limits, but rarely patrolled. His knees protested, old parachuting injuries that never quite healed right. But his mind was sharp, analyzing what he could see.

The wind was tricky today, coming from the southwest at maybe 12 to 15 mph, gusting higher. At 2,000 yd in these conditions, you weren’t just dealing with wind drift. You were dealing with the corololis effect, the actual rotation of the earth affecting bullet flight. Most shooters forgot that or never learned it properly in the first place.

He was within a 100 yards of the firing line when a Marine Corpal spotted him. Sir, sir, you can’t be here. This is a restricted training area. Robert stopped, raising his hands slightly in a non-threatening gesture. My apologies. I was just watching from the ridge and got curious. I’ll head back. But he didn’t head back.

Not immediately, because he’d seen something that bothered him professionally. The spotter, the marine lying next to the shooter with the powerful optic, was giving wind calls that were fundamentally wrong. He was reading Mirage correctly, but not accounting for the layered winds between the firing point and target.

At 2,000 yd, you might have different wind speeds and directions at 300 yd, 800 yd, 1300 y, and at the target itself. You couldn’t just read the mirage at the firing point. “They’re reading the wind wrong,” Robert said almost to himself. The corporal, a young man with a kind of high and tight haircut that screamed new marine, looked confused.

Sir, I need you to leave the area now. I understand, but that spotter is only reading near wind. At 2,000 y, they need to account for, “Sir,” the corporal’s voice had an edge now. I’m not going to ask again. You need to leave immediately or I’ll have to call the MPs. At the firing point, one of the instructors had noticed the commotion.

He was a gunnery sergeant, maybe 35, with the kind of build that suggested he spent more time in the gym than necessary. He walked over with the confident stride of someone used to immediate obedience. What’s the problem, Corporal? Civilian wandered into the restricted area. Gunny, I’m escorting him out.

The gunnery sergeant looked at Robert with the particular expression reserved for old men who don’t know their place. A mixture of patience and condescension. “Sir, this is an active training area for Marine Corps scout snipers. It’s dangerous and restricted. I’m going to have to ask you to leave.

” “Of course,” Robert said. “I apologize for the intrusion. But before I go, your team has uh been missing that target for hours. I think I know why. The gunnery sergeant’s expression shifted to something harder. Excuse me. The wind. Your spotter is only reading the mirage at the firing point.

He’s not accounting for the fact that the wind at 800 yd is probably 15° different from your position, and the wind at the target is coming from almost due west, not southwest. At 2,000 y, you’re also dealing with coriololis drift about 8 in to the right in the northern hemisphere at this range and latitude. Your shooter is compensating for wind, but not for the Earth’s rotation.

For a moment, the gunnery sergeant just stared at him.” Then he laughed, not cruy, but with the kind of amusement you’d show a child who’d just explained how rockets work using cartoon logic. Sir, with all due respect, these are Marine Scout snipers. They’re the best precision marksmen in the world. They know how to read wind, and they definitely know about Corololis effect.

From the firing point, one of the snipers called out, “Gunny, we’re ready for another attempt.” “Stand by,” the gunnery sergeant called back. He looked at Robert again, his patience clearly wearing thin. I appreciate your interest in what we do, but this is advanced long range marksmanship.

These marines have been through months of specialized training. They know what they’re doing. Then why have they been missing for 3 hours? Robert asked quietly. The question landed like a slap. The gunnery sergeant’s jaw tightened. Behind him, the Marines at the firing point had stopped their preparation and were watching the exchange.

Sir, I’m done being polite. You need to leave now. Corporal, escort this gentleman back to the public area. If he refuses, call the MPs.” Robert nodded slowly. “I meant no disrespect, gunnery sergeant. I was just trying to help.” He turned to leave, the corporal’s hand already on his elbow, when a voice called out from the firing point. “Hold on, let him speak.

” Everyone turned. The man who’d spoken was a major, older than the others, maybe 45, with the weathered look of someone who’d spent serious time downrange. He was walking toward them with deliberate steps, his eyes fixed on Robert with an intensity that suggested more than casual interest. Sir, the gunnery sergeant sounded uncertain.

The major ignored him, stopping directly in front of Robert. He was studying Robert’s face with growing recognition, his eyes moving from the faded cap to the worn jacket to something else. Something intangible that only comes from shared experience. What’s your name? The major asked. Robert Chen, sir. You prior service? Yes, sir. Marines retired in 2003.

What unit? Robert hesitated. This was always the moment he dreaded. The moment when people either didn’t believe him or suddenly treated him completely differently. First Marine Division Scout Sniper Instructor School Quantico. The major’s eyes widened slightly. Rank. Master gunnery sergeant when I retired.

And before you were an instructor. Robert sighed quietly. Second force reconnaissance scout sniper. 26 years in reconnaissance and sniper units before I transferred to training command. The major was quiet for a long moment. Then he did something that shocked everyone present. He came to attention and rendered a salute. Master Guns Chen, sir, I’m Major David Rodriguez.

I was a student in your advanced scout sniper course in 2001. You probably don’t remember me. I was one of 40 students that year, but I remember you. Everyone who went through that course remembers you. Robert returned the salute, his old muscle memory taking over. Rodriguez, you were the left tenant who couldn’t get comfortable with the M4A1.

Preferred the M24. The major’s face broke into a genuine smile. You do remember you spent extra time with me on trigger control. Said I was jerking instead of pressing. I still hear your voice every time I take a shot. The gunnery sergeant had gone pale. The snipers at the firing point had abandoned their equipment and were walking over, drawn by the sudden shift in atmosphere.

The corporal who’d been escorting Robert away had released his elbow and stepped back. “Master Guns,” Rodriguez said, his voice carrying across the range now, is probably the most accomplished scout sniper in Marine Corps history. three tours in Vietnam, two in Beirut, one in Panama, both Gulf Wars.

He has 117 confirmed kills across four decades of service. But that doesn’t come close to capturing his real contribution. He wrote the Scout Sniper Manual. Not contributed to it, wrote it. Every technique, every protocol, every windreading method you’ve been taught came from him or from instructors he trained. The gunnery sergeant looked like he wanted to disappear.

“Sir, I had no idea. I apologize.” “You were doing your job, Gunny,” Robert said gently. “I shouldn’t have been in the restricted area.” “But you were right about the wind,” Rodriguez said. “Weren’t you?” Robert looked toward the 2,000yard target, his eyes tracking the terrain between it and the firing point. At this range, in these conditions, you’re dealing with at least three distinct wind layers.

The mirage at the firing point shows southwest wind at 12 to 15 mph. But if you watch the vegetation at 800 yd, he pointed. You can see it’s moving almost due south. That’s a 15 to 20° windshift. And at the target, that flag is showing west, maybe northwest. That’s another shift. He paused, then continued. Your spotter is giving wind calls based on what he sees here, but the bullet is in flight for almost 3 seconds at 2,000 y.

It’s passing through all those wind layers, and each one is pushing it differently. You’re probably getting about 4 ft of wind drift total, but not in the direction you’re compensating for. One of the snipers, a sergeant with the lean, intense look of a true professional, spoke up. We’ve been compensating for 3.2 2 ft left.

Assuming the wind average is 12 mph from the southwest. That’s your problem, Robert said. You’re averaging winds that don’t average. The wind at 800 yd is stronger and from a different direction. It’s pushing your bullets south more than west. The wind at the target is weaker, but from the west, pushing it back east slightly.

They don’t cancel out. They compound in ways that you can’t calculate by simple averaging. You need to read each layer individually and make an educated guess about the total effect. And the corololis, another sniper asked. At 2,000 yd at this latitude, you’re looking at roughly 8 to 10 in of drift to the right.

Not enough to miss completely, but enough to turn a center mass hit into an edge hit. At extreme range, the Earth’s rotation matters. The bullet is in flight long enough that the target has literally moved slightly by the time the round arrives. Rodriguez nodded slowly. Master guns, would you be willing to demonstrate? The gunnery sergeant looked uncomfortable.

Sir, is that appropriate? I mean, no disrespect to Master Gunschen, but regulations about civilian access to weapons. Master Gunschen has more time behind a scope than everyone on this range combined. Rodriguez cut him off and he maintains his expert qualification. I checked his record while we were talking.

He still shoots twice a year at a civilian range. Still qualifies expert. He’s not a civilian in any meaningful sense. He’s a Marine. Robert felt something warm in his chest at those words. Major, I appreciate that, but I haven’t shot at 2,000 yards in years. I’m not sure. Sir, with respect, I watched you analyze this range in about 90 seconds and diagnose problems that we’ve been struggling with all morning.

I’d consider it an honor if you’d show us how it’s done. They walked to the firing point together, the group of Marines falling in around Robert like students around a master. The rifle was an M4A5, the Marine Corps standard boltaction sniper rifle chambered in 300 Winchester Magnum. Robert picked it up with reverence, his hands finding the familiar weight and balance.

It had been years, but the muscle memory was instant. He settled into the prone position, his body automatically finding the proper alignment despite his age. His bones protested. The hard ground wasn’t kind to a 71-year-old body. But once he was set, it felt right. It felt like coming home. Spotter,” he said quietly, falling into the old cadence.

The sergeant who’d been spotting moved next to him with the powerful spotting scope. “Ready, Master Guns!” Robert chambered around, the bolt sliding smoothly. He settled behind the scope, his breathing automatic, in through the nose, out through the mouth, letting his heart rate slow. The target at 2,000 yards looked impossibly small, even through the 16x magnification.

A silhouette target representing a human torso dancing slightly in the heat mirage. Wind at firing point, southwest at 12 to 15, Robert murmured more to himself than anyone else. Vegetation at 800 shows south wind stronger maybe 18. Target flag shows west at 8 to 10. Three distinct layers.

His hand moved to the elevation turret, making adjustments. Click, click, click. Then the windage turret. More clicks. He was compensating not for average wind, but for the sum of vectors, the total push across multiple wind zones, and adding that extra adjustment for corololis, those 8 in that most shooters ignored or forgot. The breathing stopped at the natural pause between breaths.

His finger rested on the trigger, not on the first joint like a novice, but in the perfect place that he taught thousands of students to find. The squeeze was so gradual that even he didn’t know exactly when the rifle would fire. The shot broke clean. The rifle recoiled against his shoulder, a familiar friend.

Through the scope, he watched. You couldn’t see the bullet at this range, but you could see the effect. 3 seconds that felt like eternity. Impact, the spotter said, his voice filled with awe. Center mass. Dead center. Robert worked the bolt, chambering another round. Once could be luck. Let me confirm. The second shot took another 3 seconds of flight.

Impact. Center mass 1 in right of the previous hole. He fired a third time. Impact. Center mass three rounds. Group size 3 in at 2,000 yd. Robert cleared the weapon, locked the bolt back, and slowly got to his feet. His knees screamed in protest, and Major Rodriguez helped him up. Every Marine on that firing line was silent, staring at the old man who’d just done in three shots what they’d been unable to do in 3 hours.

The key, Robert said, his instructor voice coming back naturally, is to stop thinking of wind as a single number. At extreme range, you’re shooting through an atmosphere that’s constantly moving in layers. Near wind, mid-range wind, far wind, they’re all different, and you need to read them all. Watch vegetation at multiple distances.

Watch mirage at multiple ranges. Look for flags, dust, anything that shows you air movement at different points along the bullet’s path. He pointed down range. At 800 yd, those bushes are moving more vigorously than anything at the firing point. That tells you the wind is stronger there. The target flag is lazy, almost limp. That tells you the wind is weaker at the target.

Your bullet spends the most time in that mid-range wind, so that’s your primary consideration, but you can’t ignore the others. The sergeant who’d been shooting stepped forward. His earlier confidence was gone, replaced by genuine humility. Master Guns, I apologize for our earlier dismissal. We were arrogant. You were confident, Robert corrected gently. There’s a difference.

Confidence is good. You need it in this job. But confidence without humility is dangerous. The moment you think you know everything is the moment you stop learning. And in our profession, stopping learning means people die. For the next two hours, Robert worked with the sniper team. He had them take turns on the rifle, coached their wind reading, taught them to look beyond the obvious indicators.

He explained the math behind Corololis effect. How the Earth rotates at about 1,000 mph at the equator, less at higher latitudes, and how that rotation affects long range shooting. He showed them how to use natural features to read wind at different distances, how to estimate wind speed without instruments, how to make rapid adjustments based on observed impact.

One by one, each sniper began hitting the 2,000yard target consistently. Not perfectly, Robert emphasized the perfection at extreme range was impossible, but reliably enough for combat purposes. The transformation was remarkable. These were already highly trained professionals, but they’d been missing a critical piece of knowledge, and now they had it.

The gunnery sergeant, who’d been so dismissive earlier, approached Robert during a break. Master Guns, I need to apologize more formally. What I said earlier, how I treated you, it was unprofessional and disrespectful. Robert studied him for a moment. Gunny, you did exactly what you should have done.

An unknown civilian wandered into your training area. You protected your marines and your mission. I don’t fault you for that, but I dismissed your knowledge without consideration because I looked like a random old man. I understand I’m a random old man most days. Robert smiled slightly. But here’s what I want you to learn from this. Never assume someone has nothing to teach you.

The moment you close your mind to learning is the moment you start failing your marines. Stay humble, stay curious, and never judge someone’s worth by their appearance. Major Rodriguez had been making phone calls during the session, and he approached Robert as the afternoon sun began its descent toward the mountains. Master Guns, I spoke with the division commander.

We have a serious problem in the core right now. We’re producing scout snipers faster than we can train them properly, and our institutional knowledge is thin. We’ve lost a lot of the lessons you and your generation learned through hard experience. Robert waited, sensing where this was going. We need instructors, experienced people who can teach the things that aren’t in the manual, the things you just taught my marines.

The core has a civilian contractor program for retired personnel. The pay isn’t much, but you’d have base access, range time, and most importantly, you’d be training the next generation of snipers, teaching them lessons that could save their lives and the lives of the Marines there, supporting. Robert looked out across the desert range, the familiar landscape where he’d spent so much of his life.

He thought about his empty house, his quiet days, the slow fade into irrelevance that retirement had become. Then he thought about the Marines he’d just trained, the way their faces had lit up when they finally hit that target, the knowledge that what he taught them might mean the difference between life and death in some future conflict.

I’d have to think about it, he said. But even as he spoke, he knew his answer. Of course. But sir, please seriously consider it. The Marine Corps needs you. These young Marines need you. Rodriguez extended his hand. And honestly, I think you need this, too. I can see it in your eyes. You’re not done serving yet.

Robert shook his hand, gripping firm despite the arthritis. I’ll call you next week with my answer, Major. But he already knew he’d already decided. Two weeks later, Robert Chen started his new position as a civilian scout, sniper instructor, consultant. He worked three days a week teaching advanced long range marksmanship, wind reading, and the accumulated wisdom of 40 years behind a scope.

The empty house in Yaka Valley was still empty, but now it was simply where he slept between the days that mattered, the days when he taught young Marines skills that could keep them alive. The gunnery sergeant who dismissed him became one of his strongest advocates, telling the story of that October day to every new class of students.

The sergeant who couldn’t hit the 2,000-yard target earned his hog, hunter of gunmen teeth, and went on to deploy to Syria, where the wind reading techniques Robert taught him resulted in confirmed kills that saved American lives. The story spread through the scout sniper community, then wider. Someone had filmed the session, captured the moment when the old man in the faded cap put three rounds center mass at 2,000 yards.

The video went viral, viewed millions of times with comments from current and former snipers around the world sharing similar stories of underestimated veterans, overlooked knowledge, and the dangerous arrogance of youth. But Robert didn’t care about viral videos or internet fame. He cared about the young Marines who approached him after class with questions, who sought his guidance, who treated him not as an old man, but as a master of his craft.

He cared about passing on knowledge that had been earned through decades of experience. Knowledge that couldn’t be learned from books or simulators, but only from time behind the glass and wind in your face. On his 72nd birthday, Robert received a package from Major Rodriguez, who’d since been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.

Inside was a custom Lipold scope engraved with a simple phrase, “Master Guns Chen, the ghost who taught us to read the wind.” Below that, a list of names, every marine Robert had trained in the past year, their signatures tiny, but present. Robert mounted that scope on his personal rifle. the old M4A3 he’d been issued during his final years of active service, restored and maintained with religious care.

He still shot with it twice a month at the Marine Corps range. Still qualified expert, still proved that age might slow the body, but couldn’t diminish skill earned through countless hours of practice and patience. Because true expertise isn’t about youthful confidence or physical prowess. It’s about knowledge accumulated over time.

About lessons learned through failure and success, about wisdom that can’t be rushed or shortcut. Robert Chen proved that on a desert firing range one October morning when he showed a new generation of warriors that the old veteran they dismissed might just be the expert they desperately needed. Subscribe to my channel if you believe that we should never judge someone’s worth by their appearance or age, and that the greatest knowledge often comes from those who’ve walked the path before us.

Share this story if you’ve ever been underestimated or learned the hard way to respect those who came before. Because the quiet old man at the firing line might just be the master who can teach you what you need to survive.