Stalin’s Cannibal Island: The Tragic History of a Soviet Labor Camp Where Thousands Died

In the frozen expanse of Siberia, where the Ob River carves through endless taiga and permafrost, lies an island shrouded in silence. Officially unnamed on Soviet maps, it is known to the few who remember as Cannibal Island—a strip of marshy land that became the stage for one of history’s most horrific experiments in human cruelty. In May 1933, amid the brutal enforcement of Joseph Stalin’s collectivization policies, this desolate patch of earth witnessed the unraveling of civilization itself. Six thousand people were abandoned there, without tools, shelter, or sustenance, in a so-called agricultural resettlement project that devolved into a nightmare of starvation, murder, and cannibalism. Over 4,000 perished in weeks, their bodies mutilated and consumed by the desperate and the deranged. The snow concealed the atrocities that summer’s grass would later reveal, but the truth lingered, suppressed by a regime that feared its own reflection.

To understand Cannibal Island, one must rewind to the winter of 1929, when Stalin unleashed decrees that reshaped the Soviet Union. Collectivization aimed to eradicate private farming, forcing peasants into state-controlled communes. Resistance was fierce. In regions like Ukraine and Kazakhstan, farmers slaughtered livestock, burned crops, and destroyed tools rather than surrender them. Stalin’s response was merciless: mass executions, deportations, and a famine that claimed millions. By 1930, urban rationing collapsed, and the internal passport system was reintroduced in December 1932, a tool to control rural exodus. Peasants without passports were deemed criminals, fueling arbitrary arrests.

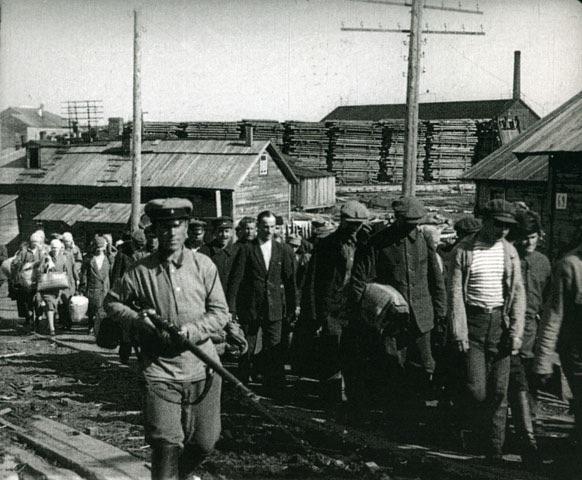

Genrich Yagoda, head of the NKVD, seized the opportunity. With a surplus of prisoners and a shortage of agricultural labor, he proposed resettling two million “undesirables” in Siberia to build collective farms. Stalin approved, but logistics faltered. In April 1933, trains dumped 25,000 people in Tomsk, a city unprepared for the influx. Local officials panicked. “Send them further north,” they urged. The Ob River offered barges, and an isolated island near Nazino village beckoned—a natural prison.

On May 14, 1933, 5,000 prisoners were crammed onto four barges. Fifty guards accompanied them. The journey was hellish: icy winds lashed the open decks, snowstorms raged, and rations dwindled to 200 grams of bread daily. By May 18, they arrived. Twenty-seven had died en route, their bodies tossed into the river. The survivors disembarked onto a 3-kilometer-long, 600-meter-wide swamp, frozen mud underfoot, scattered trees, no buildings. Among them: 322 women, 4,556 men, and the stench of impending doom.

Dmitri Alexandrovich Chepkov, the local commander, had received a February telegram to prepare for arrivals by June. But on May 5, another message: the first group was en route. The river was still frozen; nothing was ready. “Isolate them,” he ordered. The island was chosen—a watery barrier to prevent escape or looting. No one anticipated the swamp’s inhospitality.

The first night, May 18-19, was catastrophic. Prisoners huddled in the cold, building small fires with branches. Exhaustion claimed lives; burns from uncontrolled flames added to the toll. By dawn, 295 corpses lay scattered. No tools to bury them, no food to sustain the living. Guards, ensconced on barges with blankets and hot meals, watched through binoculars, orders clear: shoot anyone attempting to cross.

Hunger struck swiftly. Flour arrived on May 22, but no bread was baked. Prisoners received 200 grams of raw flour—insufficient for survival. Dysentery spread; excrement fouled the ground. By May 25, another barge delivered 1,500 more, worsening conditions. The weak died first, their bodies left to rot.

Despair bred rebellion. Prisoners organized brigades, electing leaders who received flour rations. Criminals seized control, forming gangs that hoarded food, beating dissenters. Gold teeth became currency; guards traded for bread, cigarettes, salt. Victims were attacked at night, jaws broken to extract teeth.

Cannibalism emerged. Initially, the dead were consumed—necrophagy, legal under Soviet code. But hunger blurred lines. The living became prey. A 13-year-old Ostiak girl, gathering bark in June, witnessed a gang tie a woman to a tree, carving flesh while she screamed. Pieces roasted over fires; the victim lingered, kept alive for “fresh meat.”

Bodies were mutilated systematically: limbs severed, organs removed. Human flesh hung from trees like game meat, curing in the sun. One cannibal confessed: “We skewered pieces on willow branches and grilled them.” Another preferred “livers and hearts—more nutritious.” Guards shot prisoners for sport, forced rowing contests ending in drownings, and traded sex for food.

Fyodora Belina, a 40-year-old from Leningrad, arrived in the second group. Attacked, her legs carved while alive, she crawled to Nazino village. “They ate my legs,” she whispered to rescuers. Guards arrested 50 “habitual cannibals,” executing them as scapegoats.

By mid-June, evacuation began. Of 6,700 sent, fewer than 2,200 survived. The island was abandoned, nature reclaiming the horrors.

Vasili Velichko, a Communist Party instructor, investigated rumors in July 1933. Deviating from orders, he reached Nazino in August. Grass concealed corpses—mutilated, tooth-marked bones. He interviewed Ostiaks, guards, survivors. His 11-page report detailed negligence, cannibalism, deaths. Sent to Moscow, it shocked officials but prompted damage control.

An investigative commission in November-December 1933 confirmed the atrocities. Chepkov and guards were lightly punished: party expulsion, short prison terms. Yagoda and Berman, architects, were purged in 1937-1939, but for other crimes. Survivors were scattered; many died en route.

For 50 years, silence reigned. Glasnost in the late 1980s unearthed archives. Velichko’s report surfaced in 1994, published in newspapers. Survivors testified; Ostiaks shared stories. In June 1993, locals erected a wooden cross: “To the innocent slain in the years of ungodliness.”

Annually, flowers are laid, a quiet defiance against forgetting. Cannibal Island endures as a testament to totalitarianism’s dehumanization—where ideology devoured humanity, and bureaucracy birthed monsters.

The story of Cannibal Island is not just horror; it’s a warning. Systems that treat people as statistics invite atrocities. In Siberia’s silence, the bones whisper: remember, lest it repeat.