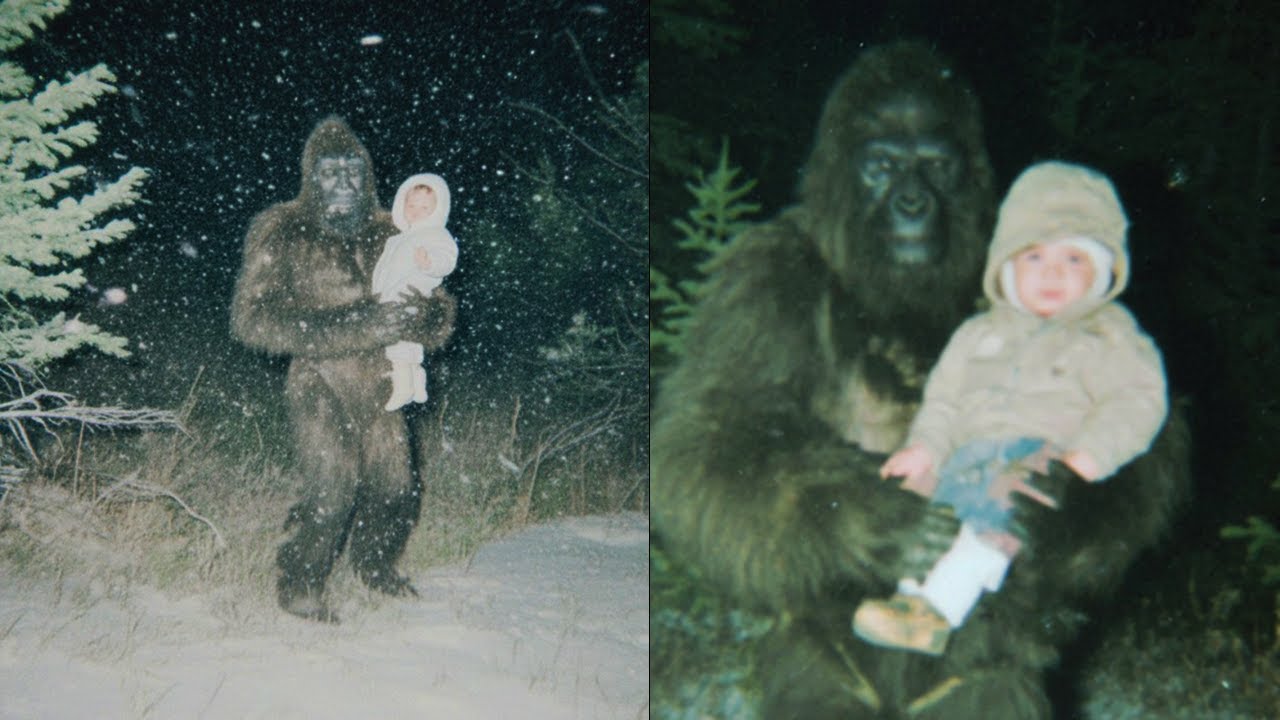

‘A SASQUATCH SAVED MY BABY’ – Hiker’s Bizarre Bigfoot Encounter Story

The Tracks in the Snow

Chapter 1: The Trail I Thought I Knew

Three years ago, I found out the hard way that the mountains don’t care how experienced you are—or how much you think you know them.

If it weren’t for something most people only talk about in jokes and grainy internet videos, my daughter would be dead.

.

.

.

That’s not exaggeration. That’s not drama. That’s the simple, cold fact I wake up with at three in the morning more often than I’d like.

I’ve been hiking in the Rockies for over fifteen years. I live in Colorado, right up against that jagged line where suburbs fall away and the Front Range rises. The mountains are basically my backyard. I’m not a tourist in brand‑new boots with a water bottle from the gift shop. I’ve done overnight backpacking, winter camping, technical climbs tied into people I trusted with my life.

I know what I’m doing out there.

Or at least I thought I did.

My wife was visiting her sister back east for a week, and I’d managed to line up some time off work. Our daughter was eighteen months old then, wobbling her way through her first weeks of walking, getting into every impossible corner of the house. She loved being outside—really loved it. Trees, birds, wind, dirt—pure joy.

We had one of those high‑end hiking carrier backpacks. She adored riding in it. Whenever I pulled it out of the closet, she’d start kicking and laughing, grabbing for the straps like a tiny mountaineer.

So I decided: easy hike, father‑daughter day. Something gentle and familiar. Sun, fresh air, some cute photos my wife could coo over from three time zones away.

I picked a trail I’d done at least fifty times.

It’s one of those family‑friendly ones every local with kids knows—two miles up to a scenic overlook, maybe a thousand feet of elevation gain. Well‑marked, well‑maintained, popular. In early spring, barring freak storms, it’s practically a nature walk.

I packed light but smart. Layers for both of us, diapers, snacks, water, small first‑aid kit, compact emergency blanket. It wasn’t a wilderness expedition, but I didn’t treat it like a stroll to the mailbox either.

The morning was perfect.

Sky that particular aggressive Colorado blue. No clouds. Mid‑fifties, barely a whisper of wind. The sort of day that makes you think nothing bad can happen because everything looks like a postcard.

My daughter was in the carrier on my back, kicking her heels against me, waving chubby hands at every bird and squirrel. Other families were on the trail—couples with kids in little puffy jackets, retirees with trekking poles. People kept smiling at us, commenting on how happy she looked, how cool it was that I had her out so young.

I’ll admit it: my chest puffed a little.

I felt like I was doing something right.

We made good time going up. She loved the rhythm of my steps, the bounce of the carrier. I stopped often: to show her a chickadee, to let her run fingers over rough bark, to pick up a pine cone and hold it in front of her so she could inspect its texture like a scientist in a tiny pink hat.

We reached the overlook around noon.

From there, the valley opens beneath you—evergreen patchwork, distant road like a grey thread, snowcaps on the far peaks. I laid out a small picnic on a flat rock, gave her some snacks. She ate, babbled nonsense, and then, just like that, conked out.

Out cold in the carrier, head flopped to one side, drool starting at one corner of her mouth. Completely at peace.

Most of the other hikers turned around then, heading back down. Smart people. It was early afternoon, plenty of time to return home, beat the late‑day chill.

I should have joined them.

Instead, my eye caught something I’d seen a hundred times and never touched.

A side trail.

A little wooden sign at the junction: LOOP TRAIL – 0.5 MI – RETURNS TO MAIN.

Half a mile. I’d always ignored it, too focused on bigger objectives, longer treks. That day, with the sky absurdly clear and my daughter sleeping and all the time in the world ahead of us, it suddenly looked… inviting. A tiny bit of newness on a trail I’d walked into the ground.

That’s where I made my mistake.

I turned onto the side trail.

Chapter 2: When the Sky Turned

The side trail started innocuously enough.

Narrower than the main route, sure, but still obviously trodden. Same packed dirt ribbon, same occasional wooden markers. It wrapped around the contour of the ridge, dipping through small stands of trees, dipping back out toward viewpoints that promised different angles on a familiar valley.

But within ten minutes, it changed.

The grade steepened. The dirt underfoot turned to loose rock and exposed roots. Trail markers thinned. The trunks around us crowded closer.

The cheery, manicured feel of a family path gave way to something more raw.

My daughter woke up.

She didn’t wake up smiling.

Fussy at first—small wriggles, whimpers. Then full‑on crying. That restless, unhappy cry that says: something’s off.

I patted her leg, spoke softly, bounced the carrier a bit in that half‑walk, half‑sway parents develop. “It’s okay, baby. Almost done. Just a little loop.”

She didn’t buy it.

The trail itself made less sense the farther we went.

Fallen logs lay across it at awkward angles, forcing me to step over or detour around. Rocks jutted up where no trail crew had come through with picks. There were blazes on trees here and there—faded paint, a faint notch—but they were irregular. I had to search for them.

The air felt different, too.

The bright open feeling from the overlook vanished as we dipped into a pocket of thicker timber. The warmth dimmed. The silence grew teeth.

I stopped.

Turned around.

And realized I didn’t like the way the route behind us looked.

Nothing jumped out as wrong, exactly. It just didn’t align with my mental picture of how we’d walked in. The junction with the main trail was nowhere in sight. The few footprints I could see in the dirt were already scuffed by my own boots.

“Okay,” I muttered, more to myself than to her. “We head back.”

I started walking the way we’d come.

Five minutes later, the trail tapered into nothing. Just scattered rocks, a few trampled weeds, then undisturbed forest.

I backtracked, eyes sharp for the last clear marker. Found it. Tried a slightly different angle.

Same result.

That’s when the weather shifted.

Up here, you learn to respect how fast the sky can change. Clouds build over the divide and tumble east in a matter of minutes. Snow can hit in June. Thunderheads can roll in out of nowhere.

But this felt unnaturally fast.

The temperature dropped first.

One moment, I was lightly sweating in my base layer. Five minutes later, a chill threaded through my jacket, raising goosebumps on my arms. It was like someone had opened a door to a walk‑in freezer.

Above, the blue bled out of the sky. A wall of dark clouds shoved over the ridge like a tide. In what felt like seconds, the sun vanished, leaving a flat, metallic light in its place.

The wind came next.

A low moan at first, then a sharper sound as it funneled through the trees. It wasn’t a steady breeze. It came in surges—brief stillness, then a powerful gust that bent branches and threw stray leaves into the air.

My daughter’s fussing turned into outright sobbing.

I pulled the carrier’s rain cover up, adjusted her hood, murmured nonsense reassurance while my mind calculated distance and time and options.

We weren’t far from where the side trail had branched.

In decent weather, with clear landmarks, it wouldn’t have been hard to find again. Here, now, with visibility dropping and my sense of direction starting to wobble, the forest felt suddenly huge.

Then the first flakes fell.

Big, wet, heavy flakes—spring snow. They stuck instantly to rocks, to branches, to my jacket. Within a couple of minutes, the ground went from mottled brown‑and‑green to patchy white. The air thickened with white streaks, turning trees into blurry ghosts.

Ten feet ahead, the trail vanished into a grey‑white wall.

I stopped walking because I couldn’t see where to put my feet.

The panic that had been simmering quietly under the surface bloomed, hot and bright.

I’ve read the reports. Hikers lost in sudden storms. Short “easy” trails turning deadly. Hypothermia, disorientation, bad decisions compounding each other until someone is lying under a tree, not getting up.

I had gear. I had experience. But I also had an eighteen‑month‑old clinging to my back, her cries growing weaker, not stronger.

That’s when the mountain started to move.

Chapter 3: The Avalanche

At first, I mistook the sound for thunder.

A low, distant rumble somewhere above us on the slope. Except it didn’t roll or crack the way thunder does. It deepened. Built. It felt less like something in the sky and more like something inside the rock.

The hair on my arms rose.

I looked uphill through the snow.

Through shifting white, I saw movement—broad, luminous, rush‑like movement. A swath of whiteness sliding downward, flattening and swallowing the trees in its path. Dark shapes toppled, disappeared.

A wave of snow and debris was pouring down the mountainside.

An avalanche.

The word slammed into me at the same moment the reality did.

The noise was incredible. Hissing, grinding, crashing, a roar like a dozen freight trains overlapping. Trees snapped like kindling. Boulders, freed by the slide, bounced and rolled, dark blurs within the boiling white.

The slide was maybe two hundred yards away when I spotted it.

It closed the distance with sickening speed.

I spun, fumbling with frozen fingers at the carrier’s buckles. They seemed to multiply, twists of nylon and plastic fighting me as I yanked. My daughter screamed, the sound pitch‑shifted by terror.

I ripped her free, pulling her to my chest, wrapping my arms around her as tight as I could. For a heartbeat, I scanned: uphill wide, downhill steep, the avalanche spray already reaching wider than our loathsome little patch of ground.

To our left, a boulder loomed out of the swirling snow. Big. Solid. Bare rock sticking like a tooth from the slope.

If I could get behind it—

I ran.

The snow was ankle‑deep, then shin‑deep. Every stride broke through crust and plunged into heavy slush. My boots slid, skidded. I clutched my daughter so hard she gasped. The boulder seemed both too close and impossibly far.

I didn’t make it.

The leading edge of the slide hit us like a body check from a moving truck.

Not the full force—not the roaring heart of the avalanche—but more than enough. The ground vanished beneath my feet. My legs flew out. The world flipped.

One moment, I was running. The next, we were tumbling.

Snow was everywhere—up my nose, down my collar, forcing itself into every gap. I tucked my daughter against my chest, curling my body around hers, willing my spine and shoulders to be the shield instead of her tiny bones.

We hit something hard. Maybe a rock, maybe a tree. Pain burst in my ribs. Another impact across my shoulder blades. A branch tore at my jacket. My knees smashed into something unyielding.

We rolled, and rolled, carried by the flow.

Time disintegrated into impacts and cold and the white roar.

Then, suddenly, stillness.

The sound cut off like someone had dropped a mute switch. It left a ringing silence behind.

I couldn’t move.

Snow encased me up to my chest, dense and heavy, holding me in a cold vise. My arms were trapped in a half‑wrapped position. My legs were pinned. My daughter was still clamped against me, my hands dug into her back and side, fingers numb.

She wasn’t crying.

“Baby?” The word wheezed out of me, shredded by my raw throat.

Nothing.

My heart tried to claw out of my chest.

I shifted what little I could, angling her enough to get a glimpse of her face. Her eyes were closed. Blood streaked her forehead where something had cut the skin. Her hat was gone. Her lips were pale.

I thought: I killed her.

Stupid, arrogant, careless—I brought her out here. I left the main trail. I walked into a storm. Now I had crushed her under my own weight, or the cold had taken her as we tumbled.

Then she whimpered.

Faint. Fragile. But alive.

I dug.

Every inch of movement was a fight. The snow was the worst kind—wet, heavy, packed by the slide. Not powder. Cement. My fingers, numb and clumsy, clawed at it, scraping layers away, making space around her first, around my chest second.

Adrenaline does things to you. It gives you strength you don’t have. It makes you think “I will move this mountain with my bare hands if I have to.”

I didn’t move the mountain. But I moved enough.

I heaved my upper body free, then my hips, then my legs, dragging us both out of the cold grave. The world around us was unrecognizable.

The forest had been erased.

Where there had been a trail, there was now a chaotic collection of snapped trunks jutting from snow, half‑buried rocks, twisted branches. The ground sloped differently. Familiar configurations of trees were gone. The carrier backpack was nowhere—not even a torn strap visible on the surface.

Everything we’d brought—food, extra layers, emergency gear—was buried under tons of snow.

My daughter started to cry.

A weak, thin sound, more air than voice. Her skin under my gloved hand felt icy. Her limbs didn’t fight when I shifted her. Her breath came in shallow little gasps.

Hypothermia can kill adults in weather like that.

An infant? Not long at all.

There was no shelter in sight. No cave, no overhang, no miraculous cabin. Just debris and snow and a storm that showed no sign of letting up.

That’s when I saw the footprints.

Chapter 4: Tracks from Nowhere

At first, I thought my vision was playing tricks on me.

Snow still fell thickly, obscuring everything past about twenty feet. My eyes were watering from cold and wind. But between downed trunks, in a narrow gap where the avalanche debris thinned, something broke the smooth surface of white.

A line of depressions.

Big ones.

I staggered closer, holding my daughter to my chest inside my jacket now, her tiny body pressed against my bare skin for warmth.

Each track was enormous—eighteen inches at least from heel to toe, maybe more. Wider than my boot by half. The shape was clear: heel, arch, ball, five toe impressions. No claws. Not that stumpy, rounded outline you get from bear paws.

The stride length between them made my knees weak. Four, five feet from one print to the next.

Whatever had walked through here had been giant, bipedal, and heavy.

There were no other sign of passage. No boot prints. No ski marks. No snowshoe craters. Just this impossible string of giant human‑like tracks cutting across the fresh avalanche debris and leading away into the trees.

In a different situation, I would have taken photos. I would have crouched, measured, examined.

Here, with my daughter’s breath growing shallower and my fingers losing feeling, I had two thoughts:

-

They were fresh. The snow hadn’t had time to fill them in.

They led away from the hell we were currently standing in.

I started following them.

The going was brutal.

The thing that made the tracks had walked as if the snow barely bothered it. Its strides cut a clean, efficient path straight through terrain that had me gasping and stumbling. I post‑holed into drifts that came up to my knees, sometimes my thighs. Obstacles—half‑buried logs, hidden rocks—caught my shins and sent jolts of pain up my legs.

Every time I fell, my daughter squirmed or whimpered, and fear jolted me back upright.

I talked to her as I walked. Nonsense words, apologies, promises. “We’re going to be okay. Daddy’s got you. Just hang on. Just a little longer. Please hang on.”

Her responses grew fewer.

The storm thickened, then thinned, then thickened again. Gusts of wind drove snow sideways, stinging my exposed skin. The trees grew older, taller, their trunks thicker, their branches weaving together overhead in a dense canopy that caught some of the snow, making the ground patchily clearer.

When I lost the tracks, I hunted until I found them again. A few times I had to walk in circles, scanning every open patch until another giant footprint appeared, reassuring and horrifying all at once.

I don’t know how long I walked like that.

Time stretched into one long, white‑blurred trudge.

My daughter’s weight seemed to triple. My arms ached. My own body began to slip toward hypothermia—shivering, mental fog, sinking desire to just sit down “for a minute.”

But the thought of my wife’s face if she came home to an empty crib kept my feet moving.

Somewhere in that blur of footsteps and labored breathing, the forest changed.

Chapter 5: The Deep Woods

The trees here were older than the ones near the main trail.

You can tell by their size—the girth of the trunks, the way their roots twist out like frozen river currents. These weren’t recent growth or second‑chance forests after logging. These were originals.

Some trunks were so wide I could have stood with my arms stretched out and still not reached halfway around them.

The air felt heavier, quieter.

Even with the storm still muttering overhead, a hush lay over this part of the forest. The kind of quiet you get in places people don’t go often, if at all.

Signs started to accumulate.

On one trunk, ten feet up, a strip of bark had been peeled away in a long, vertical section. Fresh wood showed beneath, pale against dark, with rough gouges suggesting something had gripped and torn.

On another, high branches were broken in ways no wind would cause—snapped clean, hanging down, twisted at odd angles.

The smell changed, too.

It wasn’t just wet earth and pine and cold. A musky odor threaded through, strong but not foul. Something between “wet dog” and “wild animal,” but with an underlying note I couldn’t categorize—deep, organic, old.

The tracks grew more frequent, less scattered.

They ran alongside something that looked almost like a trail—but not a human one. Vegetation had been pushed aside, not cut. Branches bent and left hanging instead of sawn off. It wasn’t neat. It was efficient.

The storm noise faded as the canopy overhead thickened. Snow still fell, but in smaller, softer patterns, filtrated by needles and limbs.

My daughter’s breath against my chest was faint, but still there.

I kept checking. Each time I felt that small ghost of a sigh warm my skin, relief shot through me, sharp enough to hurt.

The calling sound reached us then.

It started as a faint vibration under the usual forest noises, barely there under the wind in the high branches. Then it grew louder, clearer.

It was like a howl and not like a howl at the same time.

Deep. Resonant. A long note that started low in the register and rose, wavering slightly, before dropping off. It was too structured to be random. Too complex to be just an animal scream.

It came from ahead of us, somewhere in the trees.

Another call answered from off to the left. Then a third from behind. They overlapped, held, faded.

They were talking.

My rational brain knew what direction those sounds were coming from.

Toward them.

Most of my life experience suggested going the opposite way from unknown, inhuman vocalizations echoing through a secluded forest.

My daughter’s tiny, failing breaths made the decision for me.

Whatever had made the tracks had survived this storm. Whatever lived in these woods knew this terrain better than I ever would. Whatever was calling was alive.

I went toward the sound.

Chapter 6: The Fire and the Giant

The tracks led us to a stream.

It should have been frozen solid in that weather. Instead, dark water flowed under a skin of slush, burbling quietly. The banks were torn up—mud churned by something heavy. Footprints—those same impossible, wide, long impressions—speckled the edges.

The scent was stronger here, hanging in the air above the water like mist.

Trees around the stream bore more marks: bark stripped in long gouges, rough scratches at heights I couldn’t dream of reaching even if I jumped.

A fallen log had been laid across the stream at a diagonal, creating a rough bridge. It sat too perfectly positioned to be a storm casualty. Something had moved it there.

Primitive shelters tucked themselves into the spaces between massive trunks.

Leantos built of branches, pine boughs woven between them to form walls. The ground inside lined with layers of needles, moss, and what looked like animal hides. They were large—eight, nine feet long—as if built for something that would have to stoop to enter.

This wasn’t random debris.

It was a home.

A sound made me stop.

Footsteps again—but closer. Deep, soft thuds pressing into the earth with each step. They moved around me, somewhere in the trees, never fully revealing themselves. Breathing followed: slow, steady, powerful.

We were being circled.

The hair on the back of my neck stood up. My heart hammered so hard I could feel it in my teeth.

My daughter made a tiny, weak whimper.

The breathing stopped for a beat.

Then that calling sound came again—only this time, it was close.

So close I felt it vibrate through my ribcage.

It wasn’t angry. If anything, it sounded… concerned. Curious, questioning.

The trees thinned ahead, and I saw a glow between their trunks.

Orange. Flickering. Firelight.

I moved toward it.

The clearing opened suddenly, a circular space ringed by enormous trees like pillars. Snow lay unevenly on the ground, melted in a broad circle around the center where a fire burned steadily, flames licking at carefully arranged logs.

Someone knew how to tend a fire in this weather.

At first, the figure beside the flames registered as a pile of fur.

Then it moved.

Even sitting, it was taller than me.

Broad back hunched slightly over something in its arms. Shoulders like boulders. Hair—thick, dark, long—draped over it like a cape. Arms the size of small trees cradled a bundle.

The bundle moved.

My heart nearly stopped.

Wrapped in a strange amalgam of moss and pine needles and some kind of soft material lay my daughter.

Her cheeks were flushed. Her eyes were half‑open, glazed but aware. She made a soft, sleepy sound.

Alive.

The creature held her with a care that no anatomy suggested it should be capable of. One giant hand supported her back, the other cupped under her legs. Its fingers—each as thick as two of mine—curved around her without pressing.

It was feeding her.

With its free hand, it scooped a paste from a bowl—something mashed and fibrous—and offered it to her in small amounts on the tip of a finger. She accepted it, tiny mouth opening, tongue darting, swallowing.

The firelight painted the creature’s profile in warm shades.

Its face was covered in shorter fur than its body, revealing more structure. A broad, heavy brow ridge cast shadows over deep‑set eyes. The nose was wide, flatter than ours, with large, flared nostrils. The mouth was wide, lips dark, jaw strong.

The eyes—

When they lifted from my daughter and turned toward me, they were what pinned me in place.

Brown. Clear. Focused. Intelligent in a way that made the back of my mind whisper words like person and thinking and aware.

There was no surprise in them. No animal startle. Just measured assessment.

My daughter noticed me a heartbeat later.

She made a small, happy noise—the kind she made when I walked into her room after work. She reached a hand out toward me, then patted the creature’s chest as if to say, “Look. Daddy.”

I stepped into the clearing.

My legs felt like they belonged to someone else. My arms shook under the weight of adrenaline and relief and an awe that bordered on fear.

Up close, the creature was even bigger. Standing, it would have towered over me by at least two feet. Hair thick and matted in some places, clean and brushed aside in others.

It didn’t stand.

It stayed where it was, lowering its gaze slightly as I approached—as if not wanting to loom, not wanting to intimidate.

Slowly, it got to its feet.

Still holding my daughter, it moved with a controlled grace, no wasted motion. When it stood fully upright, I had to tilt my head back to meet its eyes.

It extended its arms toward me.

Gently, carefully, it placed my daughter into my waiting hands.

She was warm.

Not lukewarm. Warm. Her clothes were dry. I don’t know how—that paste on its finger, the fire, the way it had wrapped her. But the clammy cold that had turned her lips blue on the avalanche slope was gone.

She smiled up at me, sleepy and content. Then turned her head to look back at the creature, reaching one hand toward it again as if reluctant to say goodbye to her babysitter.

I looked up.

The giant’s expression—what I could read of it through fur and bone—held something like… satisfaction. Relief. It tilted its head, watching us. Then its gaze moved over my face, my gear, the scrapes on my cheek, the way I staggered slightly under my own exhaustion.

If eyes can say, You made a mess of this, but at least you made it here, its did.

It made a soft, low sound.

Not the high, carrying call from the forest. A different tone. Almost like a murmur.

Then it did something that took whatever fragments of my worldview were left and scattered them completely.

It smiled.

Not a baring of teeth, not an animal planting a threat display.

A small, subtle upward tilt at the corners of its mouth, a softening of the eyes.

Something fundamentally human.

Chapter 7: Led Out of the Wild

For a few minutes, my daughter and the creature interacted as if they’d known each other for years.

She reached out and grabbed a handful of fur on its forearm, squealing. It held perfectly still, letting her tug with no sign of discomfort. It extended one huge finger. She wrapped her tiny hand around it, babbling in her toddler language.

The creature responded.

It made a series of gentle sounds—deeper than any human could make, but modulated. Not random. Each noise had a shape, a rise and fall, an emphasis. My daughter listened, then tried to mimic, her attempts coming out as half‑garbled baby croaks.

It seemed delighted.

I stood there holding her, feeling like an intruder at a meeting of minds I couldn’t access.

At some point, the creature turned toward the fire, scooped up a small bundle wrapped in large leaves, and brought it to me. It held it out, palm up.

Inside, I found more of the paste it had been feeding her, plus a few dark berries and what looked like a carved chunk of root.

Food. For the road.

It gestured, and even through the fur and the unfamiliar anatomy, I read the meaning: Take it.

I did. Wobbling “thank you” barely made it past my lips.

It glanced toward the edge of the clearing—one particular direction, not random. Somewhere beyond the trees, the terrain sloped downward. I could feel it as much as see it. A way out.

It pointed.

Then it moved.

We followed.

Walking behind it, I realized just how adapted it was to this place.

It stepped over logs that had me clambering, ducked under branches that would have slapped my daughter in the face if I hadn’t mirrored its motions. It picked routes that avoided the worst drifts, that skirted dangerous slopes, that kept us under tree cover when the wind flared.

At steeper sections, it descended first, packing the snow with its weight, making a more solid surface for my boots. At dense thickets, it pushed branches aside with a casual strength that would have taken me minutes of hacking.

Every so often, it stopped and looked back, making sure we were still there, still upright.

My daughter fell asleep in my arms, head tucked under my chin. Her breath warmed my throat.

The storm eased as we walked. Snowfall thinned to a few drifting flakes. Clouds tore apart into ragged strips, revealing glimpses of stars overhead. The temperature remained cold, but without that knife edge of imminent danger.

The forest slowly shifted back from primeval to familiar.

Trees turned thinner, younger. Underbrush got scrappier. The smell of pine sap rose sharp and green. In the distance, faintly, I heard something unmistakably human—the distant hum of a vehicle, the thunk of a car door.

We stepped out of the trees onto a dirt road—one of those Forest Service spurs that thread up into the hills.

Tire tracks marred the snow. Far down, through gaps in the trunks, a few pale rectangles of light suggested buildings.

Civilization.

I turned to thank it.

The clearing behind us was empty.

I caught one last flicker of movement between the trunks—a dark shape melting into shadow, a hint of eyes reflecting starlight. Then nothing.

Just trees. Wind. The normal noises of a Colorado evening.

My daughter stirred, then patted my chest, murmuring what might have been one of the sounds she’d learned at the fire.

I started walking down the road.

Chapter 8: The Things We Don’t Say

The small town we reached at the bottom of that road felt like an alien world.

Neon signs. Glass windows. People in clean clothes. The hum of refrigerators. The smell of frying food.

Everyone looked at us.

Me: wild‑eyed, scraped, jacket ripped, hair full of half‑melted snow.

Her: in my arms, cheeks rosy, eyes alert, faint line of dried blood on her forehead, but otherwise shockingly okay.

The ER doctors called it a miracle.

They tossed around phrases like “remarkable resilience” and “extremely fortunate.” They poked and prodded and scanned and found nothing serious. No concussion. No internal injuries. No frostbite. No broken bones.

“She’s actually in better shape than you are,” one of them told me, half‑joking.

I had bruised ribs, a mild concussion, some strains and sprains. Nothing permanent. Nothing compared to what could have been.

Search and Rescue crews found the avalanche debris two days later.

They said it was a wonder we’d survived being anywhere near it. They couldn’t figure out how we’d gotten from point A to point B, over the terrain, in the time frame I described.

“It doesn’t add up,” one ranger murmured, looking at the map. “Not with a toddler. Not in that storm.”

I shrugged.

“We found shelter,” I said. “Dug in. Waited it out. When the storm eased, we moved. Got lucky.”

They gave each other that look people give when they want to argue but can’t without sounding ungrateful that you’re alive.

No one asked if I’d seen anything else.

I didn’t volunteer it.

What was I going to say? “Yeah, I followed giant footprints through a storm to a stone‑age village in the deep woods where an eight‑foot‑tall hairy person dried my child’s clothes and fed her mashed roots by a campfire”?

No one wants to write that down on an incident report.

So I left that part out.

We went home.

Life resumed its rhythm in the ways life does even after it’s been tilted.

My wife hugged our daughter like she would never let go again. She hugged me hard enough to bruise. I told her part of the story—the storm, the avalanche, the wandering, the “finding shelter.” I left out the creature.

Whenever I thought about adding that part, I saw disbelief in everyone’s faces before I even opened my mouth.

And underneath that, fear.

Not of the creature.

Of what it would mean if I was right.

Chapter 9: Echoes

My daughter is four now.

She doesn’t remember the avalanche. She doesn’t remember the walk down the road. If you ask her about the mountains, she’ll tell you about the time we saw a chipmunk steal a cracker, or about how she imagined dragons in the clouds.

But there are moments.

Sometimes we just drive along the highway, the Rockies etched huge against the horizon, and she’ll press her palm against the window, eyes wide.

“Can we go visit the big trees?” she’ll ask. Not “a hike.” Not “the park.” “The big trees.”

When we watch nature documentaries, she’s uninterested in lions and whales. Wolves get a little attention. But when something vaguely ape‑like comes onscreen—gorillas, orangutans—she lights up. She leans forward, eyes bright, making excited sounds.

“Friend,” she said once, pointing at a particularly shaggy silverback.

She also makes this noise sometimes.

It’s rare. It comes when she’s half‑asleep, or when she’s drowsing in my lap, or occasionally when she’s looking out a window at the tree line. It’s a low, thrumming sound, somewhere at the bottom of her register. Not quite a hum. Not quite a growl.

Every time, the hair rises on my arms.

It’s not the exact sound I heard in the forest that night. But it’s close enough to stir something deep in my chest.

When she catches me watching her when she does it, she grins.

“Daddy, you say it too,” she’ll insist. “Like this.”

I try.

My version comes out like a man with a sore throat trying to sing bass. She laughs, then shakes her head.

“You have to say it big,” she corrects, and I remember the giant form by the fire, the way it carefully made sounds at her like it was teaching, not just talking.

Sometimes, when we’re in the yard and the neighborhood is quiet, she’ll wander to the back fence and stand, looking at the thin line of trees beyond.

“Thank you,” she’ll say softly.

When I ask who she’s talking to, she shrugs and runs off.

Maybe it’s nothing. Maybe it’s coincidence. Maybe it’s the overactive pattern‑matching of a father who went through too much in one night and now looks for meaning in everything his child does.

Or maybe she remembers more than she can articulate.

Maybe somewhere, deep in the early‑formed folds of her memory, there is a warm fire, a deep voice, a massive hand offering her safety in the middle of a storm.

I don’t know.

What I do know is this:

On a day when my experience, my gear, and my judgment all failed in exactly the wrong combination, something I’d been taught was a joke stepped in and did not fail.

It found my daughter in a debris field.

It carried her somewhere warmer and safer than where I’d left her.

It dried her clothes with methods I’ll never know.

It fed her from food it had stored or gathered.

It tended a fire in a snowstorm.

It handed her back to me when I staggered into the clearing.

It led us out to where other humans could take over.

It asked for nothing.

I’ve read more since then.

Old stories. Native accounts. Settler logs. Modern “encounters” posted anonymously online. A surprising number share odd similarities: lost children describing “big hairy friends” who watched over them. Hunters who get turned around in fog and then find weird, giant footprints leading them back to familiar ground. Strange shelters found deep in the woods that no human built.

We dismiss them. It’s easier to believe in random luck and misfiring neurons than in undiscovered giants watching us from the tree line.

Maybe that’s for the best.

If everyone believed, those deep woods would fill with people hunting them. For proof. For trophies. For the sake of being the one who brought back the body.

I’ve been back in that region since.

Not to the exact spot—if I even could find it—but near. I’ve walked those trails with new caution, new humility. I carry more gear now. I check weather twice. I don’t take side trails with my kid on my back, no matter how curious they look.

Sometimes, when the day is quiet and the air hangs heavy, I’ll pause and listen.

If a branch cracks in a way that doesn’t quite fit “deer,” I don’t call out. I just nod, as if to someone watching.

The world is older and stranger than most of us like to think.

We prefer our mysteries on screens and in books, neatly contained, safely distant. But there are things out there in the wild places that don’t care whether we believe in them.

They were here before us. They’ll be here after us.

Every now and then, when the weather turns and the odds line up just wrong for some foolish human, one of them might step out of the shadows and make itself known long enough to tip the scales back towards life.

That’s what happened to me.

That’s why my daughter is asleep upstairs right now, blanket kicked half off, stuffed animal jammed under her chin.

If you ever find yourself on a mountain when the sky goes from blue to slate in five minutes, if the snow starts falling thick and wrong, if you lose the trail and see tracks in the snow that no human could have left—

Don’t assume you’re alone.

And if, by some terrible and wonderful twist of fate, you find warmth where there should be none, find safety when you’ve done everything to squander it…

Maybe don’t ask too many questions about what brought you there.

Most people get to live their whole lives thinking the world is exactly as big as they can see from their front porch.

I’ve seen a little bit past that.

It’s terrifying.

And it’s beautiful.

My daughter is alive because something impossible decided to make itself real, just long enough to hand her back.

That’s not something you “get over.”

It’s something you carry.

Like a small, warm hand in yours, tugging gently toward the tree line, toward the big trees, toward a world that will always, always be stranger and kinder and more dangerous than we think.