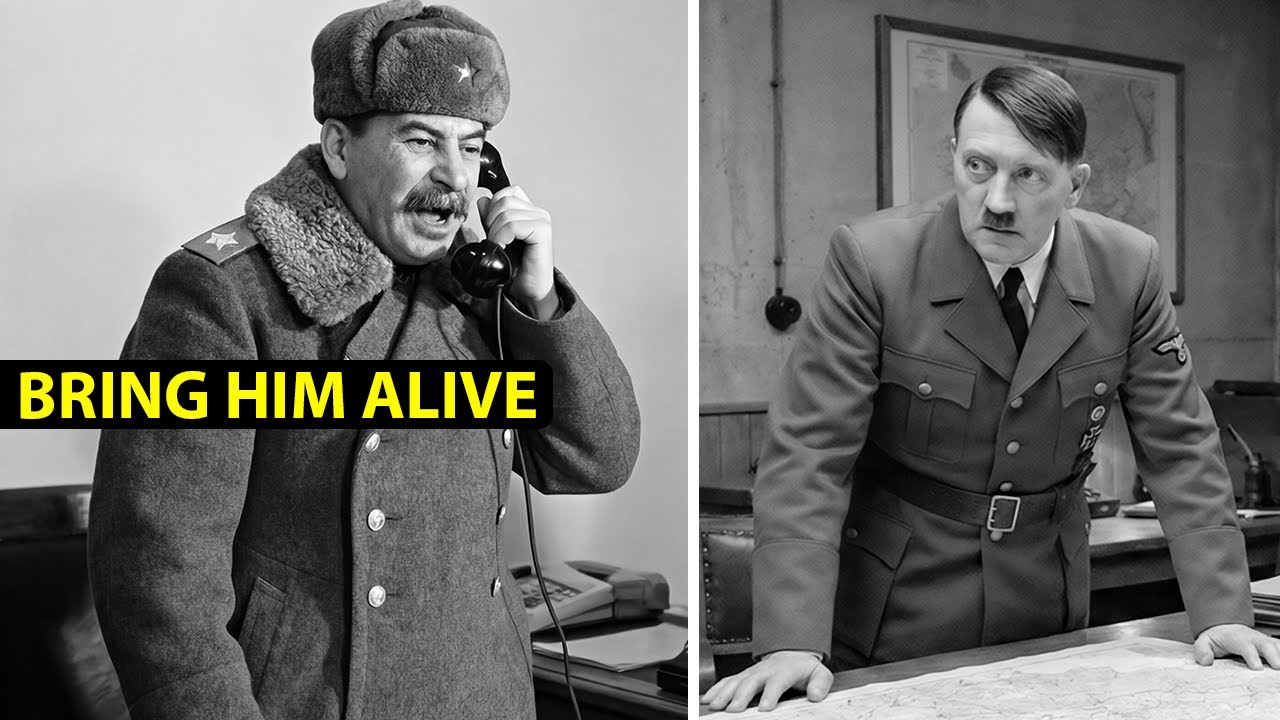

April 16th, 1945. Stalin’s message to Zhukov. Bring Hitler to Moscow in chains. Dawn doesn’t rise over the Oda River. It detonates. A wall of Soviet artillery opens up like the world just cracked in half. The ground convulses so hard even seasoned gunners blink like children. Search lights spear the fog, turning the battlefield into a white, unreal theater.

and thousands of men step into it anyway. Inside Jukov’s command post, maps are outdated before the ink dries. Phones ring without mercy. Operators whisper coordinates like prayers. Casualty numbers climb in cold, steady beats. 40,000, then more until a staff officer’s pencil freezes because the door has opened. Not a field report, not a radio signal. A courier from Moscow.

Dust on his uniform. Fear in his eyes. One envelope in his hands. Cream paper. Red wax. No return address because none is needed. Everyone in the room feels it at the same time. The Kremlin. Stalin. Zhukov looks at the seal once, just once. And the bunker goes quiet in a way artillery can’t touch.

He doesn’t open it immediately. He listens to the guns outside like he’s measuring what those words are about to cost. Then he breaks the seal, reads, and his face changes. Not dramatically, just enough. A tightening around the eyes, a shift in posture. The moment a commander stops thinking about Berlin and starts thinking about what comes after Berlin.

Because this message isn’t strategy, it’s a demand. And the words on that page don’t sound like orders. They sound like a sentence. What did that message actually say? What orders could possibly change Zhukov’s expression in a room already filled with the pressure of the largest offensive in human history? To understand that, we need to step back not to the beginning of the war, but to the beginning of the end, to the moment when Joseph Stalin stopped thinking about defeating Hitler and started thinking about capturing him. The idea

of bringing Adolf Hitler to Moscow didn’t originate on April 16th. It had been growing in Stalin’s mind for months, perhaps years, taking shape through countless late night conversations in the Kremlin. The Soviet leader never wrote it down explicitly, at least not in any document that has survived.

But those who worked closest to him understood what he wanted. Lieutenant General Alexe Antonov, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, had been passing Stalin’s intentions since the summer of 1944. He knew how the Ved operated, how he would hint at objectives without stating them directly, how he would test his subordinates, watching to see who could divine his true wishes from a raised eyebrow or a carefully placed silence.

By early April 1945, with Soviet forces masked along the Oda and the Third Reich crumbling from every direction, Antonov understood that simply destroying the Nazi regime wasn’t enough. Stalin wanted something more, something symbolic, something that would announce to the world, and especially to his increasingly difficult Western allies, exactly who had won this war and what that victory meant.

Hitler in chains, not dead in a bunker, not escaped to some South American refuge, not quietly eliminated by his own officers, alive, humiliated, and paraded through the streets of the capital he had tried to destroy. That was Stalin’s vision. That was what the message to Jukov implied in language carefully crafted to be understood without being explicit.

Marshall Alexander Vasilevki, chief of the general staff, had reviewed the message language before it went out. He had paused just long enough for Antonov to notice as he signed the authorization. Even Vasileki, who had overseen some of the most brutal operations of the war, seemed to recognize the weight of what was being communicated.

This wasn’t simply an order. This was a transformation of the entire campaign’s purpose. Colonel General Sages Demenco, head of the operations directorate, had added the final touches, timing, routting, and a single enigmatic line about special handling that everyone involved understood. The message would reach Jukov at the precise moment when the offensive began, when he was fully committed, when retreat was impossible, when every decision he made would carry the full weight of Stalin’s expectations.

But here’s what made April 16th, 1945 so much more complicated than a simple order from above. Zhukov wasn’t the only marshall receiving instructions that morning. And Stalin’s message to him carried a shadow, an unspoken threat that had nothing to do with Hitler at all. That shadow had a name, Ivan Konev. 100 miles to the south, the first Ukrainian front was launching its own offensive under KV’s command.

The two marshals had been rivals for years. Their competition carefully cultivated by Stalin himself. The Soviet leader understood that fear was only part of the equation for controlling his generals. Ambition was equally useful, and nothing sharpened ambition quite like knowing that your colleague wasracing toward the same prize.

Stalin had drawn the boundary between Jukovs and KB’s areas of operation with deliberate imprecision. The line stopped at a town called Luben, roughly 40 mi southeast of Berlin. Beyond that point, nothing. No demarcation, no clear assignment of responsibility. Both marshals understood what this meant. Whoever reached Berlin first would claim the glory.

Whoever arrived second would spend the rest of his career in the other’s shadow. So when Zukov read Stalin’s message that morning, he wasn’t just receiving orders. He was receiving a reminder. Bring Hitler to Moscow in chains, but also don’t let Konv beat you there. Don’t let anyone else claim this victory because if you fail, there’s another marshall ready to succeed.

This is the pressure that descended on Zhukov’s command post as the guns roared and the first wave of infantry began climbing the slopes of the CEO heights. This is the invisible weight that shaped every decision he would make over the next 14 days. And this is why the battle for Berlin became something more than a military operation.

It became a race against rivals as much as enemies, a test of loyalty as much as strategy, a gamble where the stakes weren’t just victory and defeat, but the very meaning of the Soviet triumph over fascism. The ceil heights rose from the Oda flood plane like a wall. Not a mountain range, not even particularly impressive by most standards, just a long gradual escarment, climbing 200 ft over the course of several miles, topped by farmland and villages that had stood for centuries.

But in military terms, those 200 ft might as well have been 2,000. Every meter of elevation gave the defenders another advantage. Every fold in the terrain offered another hiding spot for machine guns. Another position for anti-tank weapons. Another killing ground for the Soviet forces attacking uphill. General Gautard Hinrichi commanded the German army group Vistula defending this sector.

He was 63 years old, experienced, methodical, and under no illusions about his situation. He knew he couldn’t stop the Soviets. The disparity in forces was simply too vast. Roughly 2 and a half million Soviet soldiers facing fewer than a million Germans, many of them old men and teenage boys, pressed into service as the Reich scraped the bottom of its manpower reserves.

Hinrichi’s only hope was to make the victory as costly as possible, to bleed the attackers so badly that something, anything, might change the strategic situation. He had prepared the CEO heights with meticulous care, multiple defensive lines echelon in depth, carefully concealed artillery positions, fields of fire that would channel attackers into predetermined kill zones, and one particularly clever innovation, he had ordered his frontline troops to withdraw from their forward positions just before the Soviet bombardment began. The massive artillery

barrage that Zhukov had planned to destroy the German defenses fell largely on empty trenches. When the Soviet infantry advanced, expecting shattered resistance, they found Germans who had survived the bombardment and were waiting for them with weapons ready. This is where Zhukov’s first major problem emerged.

He had planned to use a technique that had worked brilliantly in previous offensives. Massed search lights pointed at the enemy positions designed to blind defenders and illuminate the battlefield for attacking troops. 143 search lights arranged along the front switched on simultaneously as the infantry went forward. The idea was sound in theory.

In practice, it was a disaster. The Oda Valley that morning was thick with fog and smoke from the artillery barrage. Instead of blinding the Germans, the search lights reflected off this murky atmosphere and backlit the attacking Soviet soldiers. German machine gunners couldn’t have asked for better targets.

The first wave of Soviet infantry advancing confidently behind their wall of light walked into a slaughter. By midm morning, Zhukov knew something had gone terribly wrong. The reports coming back from the front were confused, contradictory, and uniformly bad. Units that should have been two miles beyond the river were pinned down at the base of the heights.

Tanks that should have been exploiting breakthroughs were bogged down in marshy ground or burning on hillsides. Casualty figures that should have been measured in hundreds were climbing toward thousands, then tens of thousands. In his command bunker, Colonel Nikolai Biryukov, the front staff duty officer, logged each report with growing unease.

He had seen difficult days before. every Soviet officer of his generation had. But something about this morning felt different. The offensive wasn’t just meeting resistance. It was stalling. And somewhere in Moscow, Stalin was waiting for news. Jukov made his first critical decision of the day. At approximately 11:00, against the advice of several subordinates, he ordered his reservetank armies, the first and second guards tank armies, nearly a thousand armored vehicles combined, forward into the assault. The original plan had called

for holding these units back, using them to exploit breakthroughs once the infantry had created openings. But there were no breakthroughs. There were no openings. and the message from Stalin burned in Jukov’s pocket like a live coal. This decision would prove controversial for decades afterward. Military historians have debated whether Djukov was right to commit his armor so early or whether he should have paused, regrouped, and waited for conditions to improve.

But those historians weren’t standing in that bunker, reading that message, feeling the pressure of Stalin’s expectations and Kanev’s competition. Zjukov threw his tanks forward because he believed he had no other choice. Because delay meant disgrace. Because the man in Moscow wanted Hitler in chains and nothing less would satisfy him.

The tanks entered the battle around noon. And for a few hours it seemed like the gamble might pay off. Armor gave the Soviet forces something they desperately needed. Mobile firepower that could suppress German positions and protect advancing infantry. The CEO heights weren’t ideal tank country. Too many slopes, too many obstacles, too many concealed anti-tank guns.

But the sheer number of Soviet vehicles began to tell. By late afternoon, elements of the Eighth Guard’s army had finally crested the first line of heights. By evening, Soviet units were fighting in the village of Ceilo itself, but the cost was staggering. Jukov’s front suffered more than 30,000 casualties on April 16th alone.

Hundreds of tanks were destroyed or disabled. Some units lost 40% of their strength in a single day. The offensive had advanced barely 5 miles, a fraction of what the plan had projected. And even worse from Zhukov’s perspective was the news trickling in from the south. Konev’s first Ukrainian front was doing better.

The terrain in KV’s sector was different, lower, flatter, more suitable for armor. His river crossings had gone more smoothly. His infantry had advanced more quickly. By evening on April 16th, KV’s forces had pushed nearly 12 mi beyond their starting positions. He hadn’t faced anything like the CEO heights, and Stalin, monitoring both fronts from Moscow, had noticed.

That night, another message arrived at Jukov’s headquarters. This one came by radio and it was brief. Stalin wanted a report on the day’s progress. Not tomorrow, not through normal channels. Now, the conversation that followed, Jukov on a field telephone, Stalin in his Kremlin office has been reconstructed by historians from multiple sources.

Though the exact words vary depending on who is telling the story, what everyone agrees on is the tone. [clears throat] Stalin was displeased. Zhukov was defensive and somewhere in that conversation the unspoken competition with KV became explicit. Stalin asked why the offensive was moving so slowly. Zhukov explained about the heights, the fog, the search lights, the unexpected German resistance. Stalin listened.

Then almost casually he mentioned that KV was making excellent progress. Perhaps Stalin suggested it would be wise to shift the boundary line to let KV’s forces swing north and approach Berlin from the south while Zhukov continued to batter his way through the CEO heights. It was not a direct order.

Stalin rarely gave direct orders when indirect pressure would suffice, but Zhukov understood the implication perfectly. Either break through tomorrow or watch Konev claim the prize you’ve been fighting for your entire career. The marshall barely slept that night. None of his staff did either. Revised orders went out to every unit.

Artillery coordinates were recalculated. Fresh troops were moved forward to replace shattered formations. And at 4:00 in the morning on April 17th, the offensive resumed. April 17th was even bloodier than the first day. German defenders had used the night to strengthen their positions, bring up reserves, and prepare new defensive lines.

Soviet attacks that had succeeded on the 16th were repeated, only to find the Germans waiting for them. Tank units that had survived the first day’s fighting were thrown back into battle with barely enough time to refuel and rearm. Infantry regiments that existed only on paper. Their actual strength reduced to a few hundred exhausted men received orders to assault fortified positions as if they were still at full strength.

Through it all, Zhukov drove his subordinates relentlessly. He appeared at forward command posts, demanding results. He relieved commanders who failed to meet objectives. He pushed reinforcements into sectors that were already overflowing with troops, creating massive traffic jams that slowed the offensive even further. Years later, some of his own officers would describe these days as the most brutal they had ever experienced.

And not because of German resistance, but by the afternoonof April 17th, something began to change. The German defensive lines, however stubbornly held, weren’t infinite. Hinrichi simply didn’t have enough men to cover every position indefinitely. Soviet pressure, relentless and bloody as it was, started to find weak points.

Small breakthroughs became larger ones. Units that had been stopped for hours suddenly found themselves advancing unopposed as German defenders pulled back to new positions. By evening, Soviet forces had cleared the main CEO heights defenses. The second German line was crumbling, and ahead lay open country, relatively speaking, leading to the outskirts of Berlin, now less than 40 mi away.

That night, Stalin called again. This time, the conversation had a different tone. Zhukov’s progress was noted. Appreciated even, but the Soviet leader had another announcement to make. The boundary line between Zhukovs and Kv’s fronts was being adjusted. KV had permission to swing north.

The race for Berlin was officially a race. And the message about Hitler, it still stood. Whoever reached the Fura first would earn the privilege of bringing him to Moscow. The methods were left to the commander’s discretion. What neither Jukov nor KV fully understood was what was happening inside Berlin itself.

They knew in general terms that the Nazi regime was collapsing. Intelligence reports described chaos in the streets, food shortages, mass desertions, but they didn’t know the details. They didn’t know that Hitler had retreated to his underground bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery surrounded by a shrinking circle of loyalists and sycophants.

They didn’t know that he was issuing orders to army groups that had ceased to exist, moving phantom divisions on maps that bore no relationship to reality. They didn’t know that he had already decided to die in Berlin rather than face capture. Making Stalin’s dream of parading him through Moscow an impossibility from the start.

The man Stalin wanted to drag through the streets in chains was busy planning his own exit. But the Soviet marshals didn’t have this information on April 18th as their forces finally broke through the last defensive lines east of Berlin. All they knew was that the prize was close and both of them intended to claim it.

Konv moved first. His third guard’s tank army commanded by the aggressive and talented Pavl Ribbalo swung north on April 18th, driving toward the southeastern approaches to Berlin. Konv had direct orders from Stalin now authorization to take Berlin from the south if the opportunity arose. His tanks covered 30 mi in a single day, brushing aside German, blocking forces that were barely strong enough to delay them.

Zhukov responded by pushing his own tank armies even harder. The First Guard’s tank army under General Mik Katakov drove west toward Berlin’s eastern suburbs. The second Guard’s tank army under General Seon Bogdanov aimed for the northeastern approaches. Both commanders had received the same message from Jukov that Jukov had received from Stalin.

Berlin must be taken before anyone else claims it. What followed was one of the most chaotic advances of the entire war. Soviet tank columns raced across the Brandenburgg countryside, often bypassing German strong points rather than stopping to reduce them. Infantry units struggled to keep up, leaving long stretches of road covered by nothing but speed and audacity.

Supply lines stretched to the breaking point, then beyond it. Tanks ran out of fuel and were abandoned. Trucks broke down and were pushed into ditches. Soldiers, who hadn’t slept in 3 days, kept moving on, nothing but adrenaline and fear of their own commanders. German resistance was fierce, but fragmented.

Army Group Vistula had been shattered by the CEO Heights offensive, its remaining units scattered across dozens of miles with no coherent defensive line. Individual German soldiers and small units fought with desperate courage, knowing what Soviet capture often meant for Germans. Folkster militia men, old men and boys armed with whatever weapons could be scred, died in hopeless attacks against tanks they couldn’t possibly stop.

Vermarked regulars launched counterattacks that accomplished nothing except adding to the casualty lists on both sides. By April 20th, Hitler’s 56th birthday, as it happened, Soviet artillery was shelling the outskirts of Berlin itself. Konv’s forces had reached Zosan south of the city, overrunning the headquarters of the German high command.

Jukov’s forces had penetrated the eastern suburbs, fighting street by street through Marzan and Kurpenik. The ring around the German capital was closing, but the race wasn’t over yet. Stalin, monitoring the situation from Moscow with obsessive attention, played his two marshals against each other until the very end.

On April 20th, he drew a new boundary line. This one running directly through the center of Berlin. The Reich, the symbolic heart of German power, fell in Jukov’s sector. Sodid the Reich Chancellery where Hitler was hiding. Kv was assigned the southwestern districts. Both marshals understood what this meant. Jukov had been given the primary prize, but only if he could reach it first.

What followed was street fighting of almost unimaginable intensity. Berlin in late April 1945 was a city in the final stages of collapse. Allied bombing had reduced entire districts to rubble. Fires burned unchecked for days. Civilians hid in basements and subway tunnels, emerging only to search for food or water.

German soldiers, SS fanatics, and armed Hitler youth fought from building to building, knowing that surrender often meant death, and that defeat certainly meant the end of everything they had believed in. Soviet forces adapted tactics that had been developed at Stalingrad. combined arms teams of infantry, tanks, and artillery working together to clear buildings methodically.

A typical assault on a fortified building might begin with tank fire to suppress defenders in upper floors, followed by infantry clearing room by room, while sappers prepared demolition charges for bunkers and strong points. Progress was measured in blocks, sometimes in individual buildings. Casualties mounted on both sides with every passing hour.

Through it all, Zhukov kept his eyes on two objectives, the Reich and the Reich Chancellory. These buildings represented more than military targets. They represented the physical embodiment of Stalin’s demand. Take these and the war was won. Take these and the promise of Hitler in chains or Hitler dead at minimum could be fulfilled.

On April 28th, Soviet forces reached the Malta Bridge over the Spree River, less than a quarter mile from the Reichtag. German defenders had fortified the area with everything they had left. Anti-tank guns, machine gun nests, mines, and several thousand troops who knew they were making their last stand.

The bridge itself had been partially demolished, but remained passable with care. Beyond it rose the massive burned out shell of the Reichag building. Its dome shattered, its walls blackened but still standing. The assault on the Reichtag began in earnest on April 30th, 1945. Soviet commanders had assigned the honor of capturing the building to specific units, understanding the symbolic importance of being first to raise the red flag over the enemy’s parliament.

Competition between regiments was almost as fierce as the competition between Zhukov and KV. Multiple assault teams approached the building from different directions, each hoping to claim the prize. The fighting inside was brutal. German defenders had turned the Reichtag into a fortress with barricades on every floor and firing positions in every window.

Soviet soldiers fought their way up staircases choked with debris, clearing rooms with grenades and submachine guns, stepping over bodies of comrades and enemies alike. Some accounts describe hand-to-hand combat in darkened corridors, bayonets and rifle butts used when ammunition ran out. And then sometime in the late afternoon or early evening, the exact time is disputed, Soviet soldiers reached the roof.

Multiple flags were raised that night by different soldiers at different times in what appears to have been a chaotic competition for glory. The famous photograph showing two Soviet soldiers raising the red banner over the Reichag was actually staged several days later for propaganda purposes. But the reality was just as significant.

By the evening of April 30th, Soviet forces controlled the building that symbolized German power. That same evening, less than half a mile away, Adolf Hitler shot himself in his bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery. He had married Ava Brown the day before. He had dictated his final testament, blaming the Jews for the war, and exhorting the German people to continue the struggle.

He had said goodbye to his staff, distributed poison capsules, and given orders for his body to be burned so that it would not fall into Soviet hands. Then he had retreated to his private quarters with his new wife and a pistol. Stalin’s dream of bringing Hitler to Moscow in chains died with that single gunshot.

But the message, that sealed envelope with the red wax delivered to Jukov’s command post as the guns opened fire on April 16th, had already done its work. Not because it succeeded in capturing Hitler alive, but because it had transformed the final battle of the European War into something more than a military operation. It had made Berlin personal.

It had made the victory symbolic in ways that would shape the postwar world for decades. Soviet forces didn’t learn of Hitler’s death until May 2nd when German generals finally emerged from the rubble to negotiate surrender. By then, the fighting in Berlin was largely over. KV’s forces had linked up with American units on the Ela River.

Zhukov’s forces controlled the city center. More than 300,000 German soldiers had surrendered in and around the capital. The Reich,which Hitler had promised would last a thousand years, had ended after just 12. The cost of those final two weeks was staggering. Soviet forces suffered approximately 80,000 killed and more than 270,000 wounded in the Berlin operation.

casualties on a scale that would have been considered catastrophic for any Western army. German military and civilian deaths in the same period probably exceeded 100,000, though exact figures will never be known. The physical destruction of Berlin was almost total, leaving millions homeless in the ruins of what had been one of Europe’s greatest cities.

And for what? The question has haunted historians ever since. Some argue that the Berlin offensive was militarily unnecessary, that Zhukov and Kv could have surrounded the city, cut it off from supplies, and waited for surrender without the bloodshed of a direct assault. Others point out that German forces in the west were surrendering to Americans and British rather than face Soviet captivity, and that allowing Berlin to fall without Soviet conquest might have shifted the postwar balance of power in ways Stalin couldn’t accept.

Still others suggest that the offensive was as much about Soviet domestic politics as international strategy, that Stalin needed the dramatic victory to consolidate his own position and justify the terrible sacrifices his people had endured. What seems clear in retrospect is that Stalin’s message to Jukov, the sealed envelope, the red wax, the demand for Hitler in chains, represented something larger than a single objective.

It represented the Soviet leader determination to shape the narrative of the war’s ending to ensure that the final victory over fascism would be seen first and foremost as a Soviet victory to claim not just the territory of Eastern Europe but the symbolism of having destroyed the Nazi regime at its heart. Zhukov understood this even if he didn’t approve of the methods.

years later after Stalin’s death, he would write critically about the Berlin operation and its costs. But in April 1945, standing in his command bunker as the guns roared and the casualties mounted, he had no choice but to obey. The message from Moscow left no room for interpretation, no room for delay, no room for the kind of cautious professionalism that might have saved thousands of lives. and Konv.

He reached Berlin, but not the prizes that mattered most. His forces captured Zusen, overran suburbs, and linked up with Western allies. But the Reichag flew Zhukov’s flag. The Reich Chancellery fell to Zhukov’s troops. In the history books, Berlin would forever belong to the commander of the first Bellarussian front.

Stalin’s competition had produced exactly the result he intended. As for Hitler’s body, it was burned in the Chancellory Garden as he had ordered, then buried and exumed and transported and examined and re-eried so many times over the following decades that the full story is still disputed. Soviet authorities initially claimed they couldn’t confirm his death, perhaps hoping to maintain the fiction that he might still be captured.

Later, the remains were reportedly destroyed entirely, scattered so that no grave could ever become a shrine. Stalin never got his parade, never got his chains, never got the symbolic humiliation he had wanted so badly. But he got something else. He got the narrative he needed. The story of Soviet forces fighting their way into the heart of Nazi Germany, raising the red flag over the Reichag, ending the war that had cost his country 27 million lives.

The story that would justify everything, the purges, the goologs, the enforced suffering of generations, because it ended with victory over the greatest evil the 20th century had produced. The sealed envelope that arrived at Jukov’s command post on the morning of April 16th, 1945 was never made public. Its exact contents remain classified or destroyed or simply lost in the chaos of the war’s ending.

What we know comes from memoirs, from interviews, from the recollections of staff officers who stood in that bunker and watched their commander’s face change as he read. But the effect of that message, the pressure it created, the competition it intensified, the human cost it arguably inflated shaped the final battle of the European War in ways that are still being debated.

It turned the conquest of Berlin from a military operation into a political statement, from a strategic necessity into a symbolic crusade, from an ending into a beginning. Because the cold war that would dominate the next 45 years of history really started in those two weeks. In the race between Zhukov and Kv, in the tension between Soviet and Western forces meeting on the Ela, in Stalin’s obsessive need to claim not just victory, but the meaning of victory.

The world that emerged from the rubble of Berlin in May 1945 was already divided, already suspicious, already armed, already preparing for the next confrontation. The guns fell silent onMay 8th, 1945 when Germany officially surrendered. Soviet soldiers celebrated in the streets of Berlin, firing weapons into the air, embracing comrades who had survived, mourning those who hadn’t.

Zhukov accepted the German capitulation at a ceremony in Carl’shost, signing documents that formally ended the war his country had been fighting since June 1941. But somewhere in the background of those celebrations, the memory of Stalin’s message lingered. The reminder that even in victory, Soviet commanders served at the pleasure of a man whose demands were never quite satisfied, whose expectations were never quite met, whose approval was always conditional, always temporary, always subject to revision.

Zhukov would learn this lesson personally in the years that followed. Despite his victories, despite Berlin, despite the Reichag, despite everything he had accomplished, Stalin would eventually demote him, exile him to minor commands, strip him of influence. The man who conquered Berlin would spend years in disgrace, rehabilitated only after Stalin’s death in 1953.

The sealed envelope was just the beginning, a preview of a future where loyalty mattered less than usefulness, where heroes were disposable, where the very victories that saved the Soviet Union would become liabilities for those who won them. But none of that was visible on the morning of April 16th, 1945, when the guns opened fire and the message arrived.

All Jukov knew then was that Berlin lay ahead, that Stalin was watching. that failure was not an option. And so he pushed forward through the CEO heights, through the Brandenburgg countryside, through the burning streets of the German capital, to the Reich and the bunker and the body in the garden, to the end of the war and the beginning of everything that came after.

The search lights that had blinded his own men. The tanks that had burned on the hillsides. The soldiers who had died by the tens of thousands anonymous and forgotten. Their names recorded only in archives that no one would read. All of it was part of the price Stalin demanded. All of it was contained somehow in that sealed envelope with the red wax.

All of it was the cost of bringing Hitler to Moscow in chains. Even though Hitler never made the Ye Journey, your support helps us continue the deep research behind every episode. Buy us a coffee and fuel the next documentary. Link is in the description. If this story showed you something new about how World War II ended, consider subscribing to the channel and sharing this video with someone who might find it meaningful.

More stories from history’s most decisive moments are coming soon.