A six-pound pump shotgun with a design flaw the factory never fixed became the most devastating close quarters weapon of the Vietnam War and the military bought 60,000 of a cheaper gun instead. June 1970 Tan Sunnut Air Base, Vietnam. An Air Force colonel stops a Navy Seal in the corridor and stares at the weapon hanging from his neck. short, ugly.

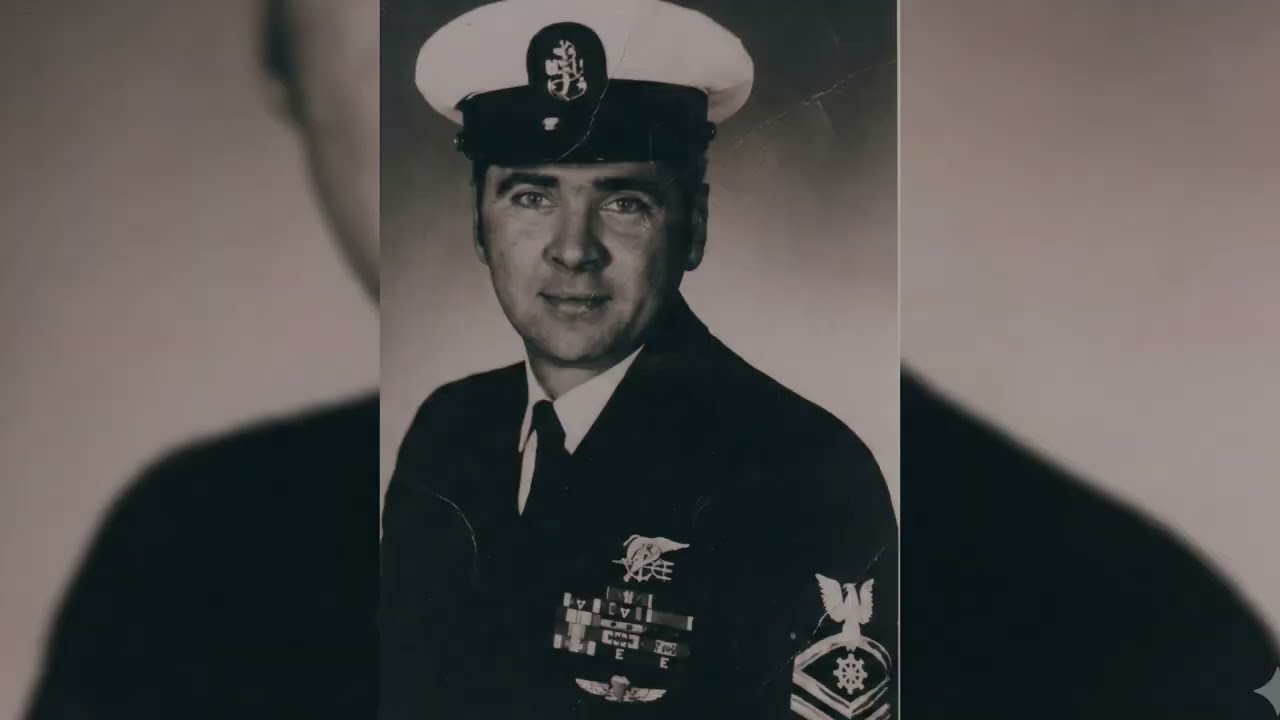

The barrel is fitted with something that looks like a crushed metal beak. The colonel asks what it is. The seal, Senior Chief James Watson, three combat tours, 16 decorations, looks him dead in the eye. That’s my sweetheart, my 12 gauge. The colonel tells him that shotguns are against the Geneva Convention. Watson doesn’t blink.

Colonel, if they ever send me to Geneva, I’ll leave her at home. But between now and then, she and I just don’t part company. That shotgun, an Ithaca Model 37, could put 72 buckshot pellets into a kill zone in under 3 seconds. It could be dunked in a muddy creek and fired the moment it came out. It weighed less than an empty canteen and a bag of rice combined.

This is not a story about the most popular weapon in Vietnam. That was the M16. It’s not about the most issued shotgun, the Stevens 77E, which the Pentagon bought 60,000 of because it cost $5 less per unit. This is the story of the shotgun that elite operators chose when their lives depended on it. By 1965, every weapon in the American arsenal was built for a war that hadn’t started against the Soviets across the open plains of Europe.

Fast jets, long range rifles, nuclear delivery systems, a thousand-y war. Vietnam was 10 yards. The air in the Meong Delta sat on your chest like a wet sandbag. Everything smelled of canal rot and burned diesel and the sweet decay of vegetation that never dried. The jungle was never quiet. Cicas screaming, water dripping off broad leaves until it went silent.

And when it went silent, someone was about to die. Over 80% of firefights erupted at 30 m or less. More than half of all ambushes happened inside 15 m, the length of a school bus. At that distance, the fight was over before your brain finished processing the first shot. The M14 was too long for the jungle.

The M16 jammed when it got dirty, and everything got dirty. Into that gap stepped a weapon most officers considered a relic, a police riot gun. The pointman knew better. The pointman walked first in the column, ahead of everyone. His job was to find the ambush by walking into it. He needed a weapon that forgave bad aim and punished everything in front of it.

And there was only one shotgun in the inventory built for what the jungle would do to it. The Ithaca Model 37 had three things no other combat shotgun offered. All three mattered in Vietnam, and the third turned it into something no one at the factory ever intended. First sealed sides. Every other pump shotgun ejected shells from a port on the right side of the receiver.

Open a hole into the guts of the weapon. In monsoon mud, that hole killed the gun. The Ithaca was loaded and ejected from the same bottom port. Both sides solid mil steel. No opening. Watson could dip his Ithaca into a creek, wash the mud out, and fire it on the spot. Nobody said that about the Stevens. Second weight, 6.3 lb.

Lightest combat shotgun available. The Remington 870 weighed over 7. The Winchester 1897 pushed 8. When you’re humping 85 lbs through triple canopy, a pound and a half is another magazine of ammunition. Third, the thing the factory never fixed. The Ithaca 37 had no trigger disconnector in any normal shotgun. Remington Stevens Winchester 1,200.

You pull the trigger, fire, release, pull again. The Ithaca didn’t work that way. Hold the trigger back and pump the action. The gun fired the instant the bolt locked forward. No pause, no reset. They called it slam fire. Five rounds of 000 buckshot. 45 pellets in under 3 seconds with the extended eight round tube that SEAL armorers brazed onto Watson’s gun.

72 pellets, each one 33 caliber, all of them hitting a space the size of a doorway. A joint service report found that the probability of hitting a man-sized target with a shotgun was 45% greater than a submachine gun burst, twice that of an assault rifle. The Steven 77E couldn’t slam fire. Its aluminum trigger guard snapped under recoil.

Its birch stock painted to look like walnut cracked at the receiver. In the 25th Infantry Division, a rifleman named Specialist Fourth Class Danny Kio was walking second in the column when the pointman Steven split at the wrist during an ambush near Coochi in late 68. The point man racked the pump and the for came off in his hand.

Kog had to cover the gap with his M16 while the point man scrambled for a sidearm that wasn’t there. Kog told his platoon sergeant that night, “The next shotgun that comes in, he wanted the Ithaca. He got one 3 weeks later and carried it until he rotated home.” Bruce Canfield, the leading authority on American military firearms, wrote that the Stevens was plagued by some nagging reliability problems, while the Ithaca generally gave excellent service.

The government bought the Stevens at 3150 per unit. The Ithaca cost 3661, $511. That’s what separated the gun that shook itself apart from the gun that never quit. Senior Chief James Patches Watson III was a founding member of SEAL Team 2. He walked point every time on behind the lines missions through the Delta from 1967 to 1970.

Three tours, four Bronze Stars with Combat 5. After his first tour with a standard Ithaca, Watson went to Frankfurt Arsenal and had armorers build him something specific. Extended magazine, eight rounds, a duck bill spreader choke welded to the muzzle. Stock cut to a pistol grip. The whole thing hung from a sling around his neck.

The duck bill changed the geometry of killing. Standard buckshot spreads in a circle. Half your pellets go into the dirt or the canopy. The duck bill flattened that circle into a horizontal blade four times wider than tall. It was built to catch three men walking a breast on a narrow trail. It didn’t just hit the target, it cleared the path.

Watson loaded it with number four buckshot, 27 pellets per shell instead of nine. At 20 yards, what he called long range in the delta, that horizontal cloud had no gaps. Nothing standing in front of it stayed standing. His assessment of its effect. The VCI shot didn’t seem to complain. The Navy also gave Watson a Remington 7188, a select fire automatic shotgun.

He called it finicky and fragile. It choked in the mud. The Ithaca never did. Watson could slamfire it with the speed of an automatic and clear a jam by racking the pump once. No battery, no gas system. Just milled steel, a spring, and the fastest hands in seal team, too. Three tours cost something.

Watson didn’t talk about the nights much. In one interview decades later, he mentioned that he still slept with a weapon within arms reach. Not because he thought anyone was coming, because his hands didn’t believe the war was over, even when the rest of him did. Sweetheart is behind glass now at the UDT Seal Museum in Fort Pierce, Florida. But Watson was the elite.

The vast majority of men who carried shotguns in Vietnam were not SEALs. They were 19-year-old drafties walking point because it was their turn. And what they experienced on both ends of that weapon deserves its own telling. At 5 m, a tunnel entrance, a trail bend, the instant a patrol walks into an ambush. Nine pellets of 000 buckshot arrive as a single fist-sized mass.

Penetration exceeds 18 in in ballistic gelatin. Front to back through a human torso with energy to spare. At 10 m, the pattern opens to 8 to 10 in. All nine still inside the chest. At 25 m, 16 in. every pellet accountable on a man-sized target. One trigger pull, one pump, and another nine are on the way. Captured VC documents and interrogation reports indicated that enemy troops would sometimes cease fire and withdraw at the sound of a pump action cycling, knowing the aircraft overhead might leave, but the shotgun wasn’t going anywhere.

The Germans learned this first. September 15th, 1918. Germany protested American shotgun use in the trenches. Unnecessary suffering. Threatened to execute any American P caught carrying one. The US Judge Advocate General Samuel Ansel noted the protest came from a nation deploying chlorine gas, flamethrowers, and serrated bayonets.

Germany never replied. That myth followed the shotgun to Vietnam. Watson’s colonel wasn’t alone. The Army’s own law of war deskbook states it plainly. Shotguns have never been prohibited by any international treaty. But here’s what the shotgun story always leaves out. The point man carried five rounds. The M16 carried 20.

100 shotgun shells weighed over 10 lb. 100 rifle rounds weighed under three. In a sustained fight, the shotgunner ran dry in seconds, feeding shells one at a time. No magazine, no speed loader, just fingers and pockets. The Ithaca 37 was the deadliest weapon in Vietnam inside 20 yards. Past that, it was 6 lb of dead weight.

Roughly 700 men served as tunnel rats during the war. They crawled into holes 2 ft wide carrying 45 pistols and 38 revolvers. Medal of honor recipient command. Sergeant Major Benny Atkins carried a sawed off 12- gauge during the 4-day battle of AA in March 1966. All he said about it, I did use it. I did. and a lot of hand grenades. 47,000 Ithaca 37s went to Vietnam.

60,000 Steven 77 shipped alongside them for $5 less a piece. The Remington 870, the gun that eventually replaced everything, barely arrived before the war ended. Its purpose-built military version wasn’t contracted until May 1969. Few if any saw combat. After the war, the military standardized on the Remington and the Mossberg.

The Ithaca was too expensive to manufacture. Its slamfire made peaceime safety officers nervous. The gun that worked was quietly retired because it cost too much. That pattern hasn’t changed. 50 years later, procurement still picks the lowest bid. Soldiers steal field equipment that meets the minimum spec and pray it holds when the shooting starts.

Today, a Vietnam era S prefix Ithaca 37 serial numbers between 1,000 and 23,000 stamped US on the receiver is one of the most sought after military collectibles in the world. And if you go to Fort Pierce, Florida, and stand in front of the glass case at the UDT Seal Museum, you can see Sweetheart, the extended tube, the duck bill choke, the pistol grip Watson cut himself.

It doesn’t look like much. It looks like something a man built in a hurry because the thing the government gave him wasn’t good enough to keep him alive. $511. That’s what separated the gun that fell apart from the gun that never did. In a jungle where the fighting happened at 15 m in the dark in the rain. That was the distance between walking out and being carried.

Watson carried Sweetheart on a sling around his neck for 3 years. They asked him once why he never switched to something newer. He said the same thing he’d said since 1967. She and I just don’t part company.