Four Hours With Bigfoot: The Creature’s Terrifying Revelations About Our World Become a Chilling Sasquatch Folklore Tale

In the high, dry plains of Montana, where the wind scours the earth and the sky stretches tight as a drum skin, they tell the story of Herbert Fletcher.

To the people of the valley, Herbert was a man made of dust and routine. He was a farmer of the old breed, a man who measured his life in bushels of corn and gallons of diesel. He lived on two hundred acres of inheritance, in a house that had grown too quiet since his wife, Margaret, passed into the earth. His children had fled to the cities, chasing the bright lights and the hum of the new world, leaving Herbert alone with a border collie named Sam and a silence that filled the rooms like water.

It was the Summer of the Great Heat, a time when the thermometer refused to drop below ninety, even in the dark. The corn was thirsty. The earth was cracking. And Herbert Fletcher was a man sleepwalking toward his own end, grinding his gears against the changing world.

But the land remembers what men forget. And on a humid night in August, the land sent a messenger.

It began with the dog. Sam was a creature of courage, but that night, by the machine shed, he turned to stone. He did not bark. He did not charge. He pressed his belly to the dust and whimpered, his eyes fixed on the wall of corn that bordered the deep woods.

Herbert took his heavy flashlight, the beam cutting a cone through the dark. He walked toward the rustling, expecting a bear or a thief.

“This is private land,” he called out, his voice thin against the vastness of the night. “Show yourself.”

The corn parted. And the world Herbert knew ended.

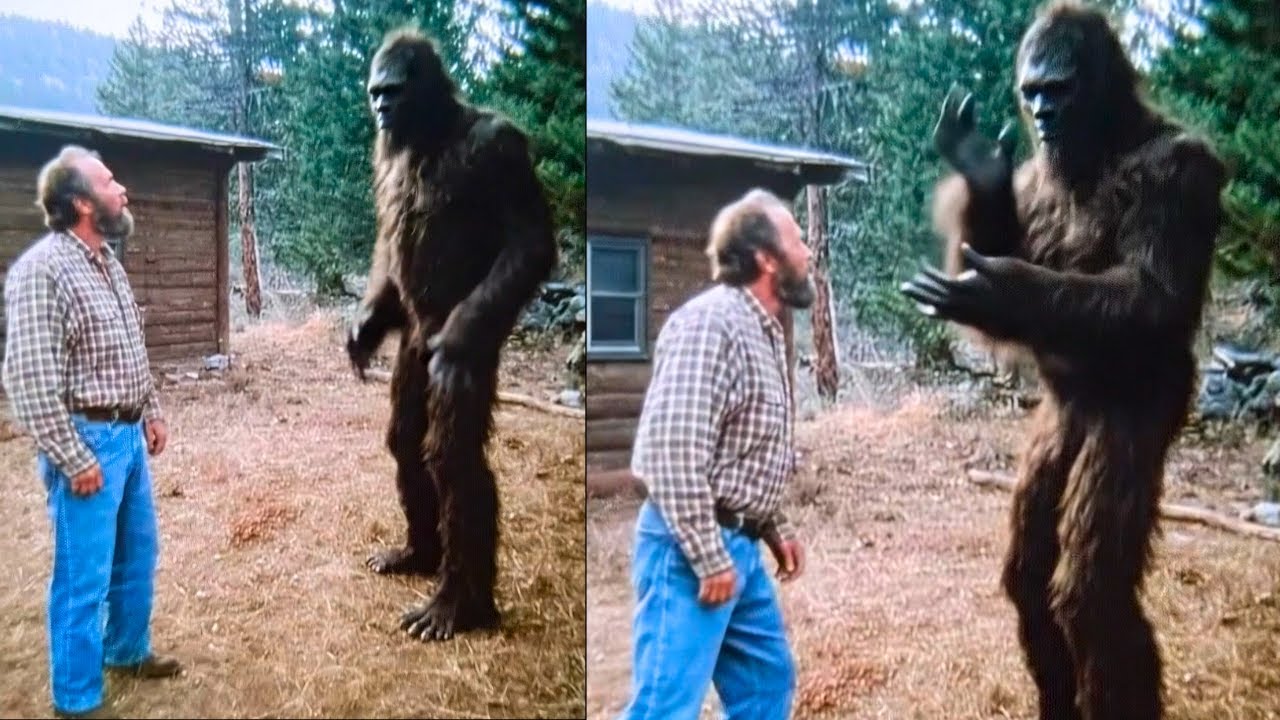

It was not a man. It was not a bear. It was a tower of shadow and copper-colored fur, standing seven and a half feet tall. It stepped from the stalks with a silence that defied its size. Its shoulders were mountains; its arms were heavy boughs. But it was the face that stopped Herbert’s heart.

It was a face of ancient, terrifying intelligence. The brow was heavy, the nose flat, but the eyes—amber in the flashlight’s beam—held a spark of consciousness that stripped Herbert bare.

Herbert stood frozen. Reason told him to run. Instinct told him to fight. But something else—perhaps the soul of the farmer who knows that all life is kin—told him to wait.

The Giant raised a hand. It was a gesture of peace.

Herbert, trembling, raised his own.

The creature spoke. It was not a language of words, at first. It was a rumble, a vibration in the chest. And then, slowly, painfully, it shaped the sounds of men.

“No… hurt. Talk.”

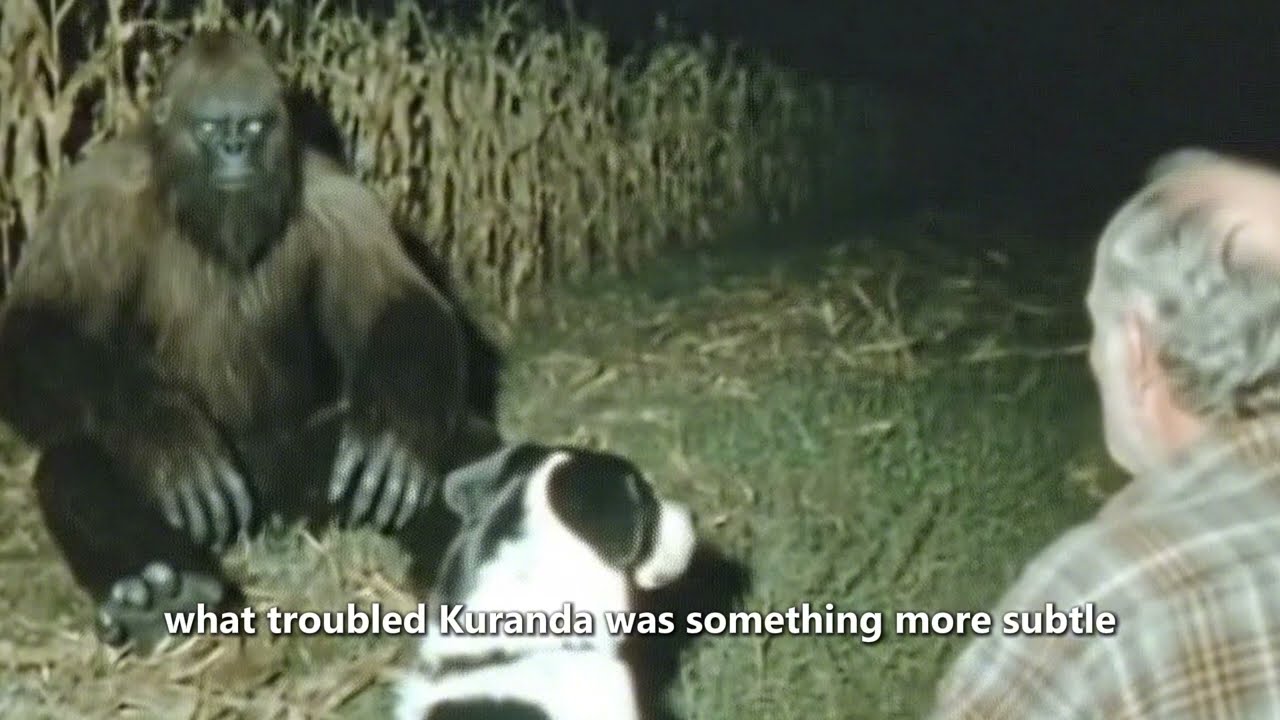

Herbert sank to the dirt. The Giant sat cross-legged, a mirror of the man.

“I am Herbert,” the farmer whispered.

The Giant touched his own chest. “Kuronda.”

They sat for four hours, the Farmer and the Watcher, while the crickets sang the chorus of the night.

Kuronda spoke in broken stones of words, gleaned from decades of listening to the voices of men from the tree line. He told Herbert that he had watched him. He had watched his father. He had watched the grandfather who first broke the sod.

“I watch,” Kuronda rumbled, his voice like grinding gravel. “Long time. Watch humans change.”

“Change how?” Herbert asked.

Kuronda stood and walked to the edge of the corn. He ran a massive hand along the stalks.

“Before… humans take some, leave more. Forest stay. Animals stay. Balance.” He swept his hand over the monoculture, the endless rows of identical crops. “Now… humans take all. Plant one thing. Kill everything else. No balance.”

Herbert felt the sting of truth. “We have to feed the world,” he defended. “We need efficiency.”

“Efficiency,” Kuronda tasted the word, spitting it out like a bad seed. “I hear this word. Productivity. More. But I watch you, Herbert. You work harder. You have machines. But you are happy less. You are alone more.”

The Giant leaned in, his amber eyes burning.

“Humans forget how to be quiet,” Kuronda said. “Always noise now. Machines. Boxes with pictures. Noise outside, so never hear inside.”

He spoke of the “Cliff.” He told Herbert that humanity was running through a dark forest, faster and faster, chasing a light that was not the sun.

“You see the Cliff,” Kuronda said. “Your scientists say it. The weather says it. The water says it. But you run faster. You think you can fix it later. But later is now.”

He spoke of the heat. He spoke of the water table dropping. He spoke of the loneliness that was eating the hearts of men.

“Worst thing,” Kuronda said, his voice dropping to a whisper that shook the leaves. “Humans stop trusting. Stop helping. When the bad times come—and they will come—humans will be alone. That is what terrifies me. Not the fire. Not the drought. But the silence between people.”

As the first gray light of dawn touched the east, Kuronda stood.

“Why tell me?” Herbert asked, his soul shaken.

“Because you have land,” the Giant said. “You work with earth. You are a bridge. My people hide because we are afraid. But I am old. If I do not try to help, I will regret.”

He backed into the shadows. “Tell others. Humans need to slow down. Be quiet. Listen. Remember you are one family. What hurts one, hurts all.”

And then he was gone, leaving Herbert with a notebook of madness and a heart full of seeds.

Herbert Fletcher did not sleep. He sat on his porch, watching the sun rise over a farm that suddenly looked like a factory.

He went into his house. He walked past the television that had been his only friend. He went to the room where his wife, Margaret, had kept her books. He read the words she had loved—words about stewardship, about the sacredness of the soil, about the web of life.

He realized that Kuronda was not a monster. He was a mirror.

Herbert began to change. It was slow at first, like a sprout pushing through hardpan.

He stopped spraying the edges of his fields. He let the hedgerows grow wild. He planted cover crops instead of leaving the earth bare and bleeding. His neighbors laughed. They called him a fool at the feed store. They said he was going backward.

“Survival is not about going forward,” Herbert told them. “It is about adapting.”

He went to the church. He spoke to the Reverend. He didn’t speak of the Giant; he spoke of the loneliness. He spoke of the soil that was turning to dust.

“We are running toward a cliff,” Herbert told the few who gathered in the basement. “We need to learn how to stop.”

They started a group. Fifteen people. Farmers, teachers, the lost and the worried. They talked about the water. They talked about the debt. They talked about the fear that woke them in the middle of the night.

They began to help one another. They shared labor. They shared seeds. They built a community in the shadow of the machine.

A year passed. The farm changed. The monoculture was broken by patches of prairie, by wild flowers, by life. The birds returned. The soil began to hold water again.

One evening in June, as the sun set the sky on fire, Herbert felt the eyes again.

He turned to the tree line. Kuronda was there. But he was not alone. Two smaller figures stood beside him—juveniles, watching the man with wide, curious eyes.

Herbert raised his hand. The three figures raised theirs. It was a covenant. A promise kept.

But the world was turning darker. The heat grew worse. The fires in the west turned the moon blood-red. The anger in the towns grew sharp and brittle.

Four years after the first meeting, Kuronda returned. He looked old now, his fur silvered with time, his movements slow.

He sat with Herbert in the dark, drinking coffee from a thermos, eating apples with a gentle grace.

“I come to say goodbye,” Kuronda said. “My time is short.”

“I have tried,” Herbert said. “I have built the community. I have healed the soil.”

“You have done good,” Kuronda rumbled. “But the storm is coming. The weather will break. The systems will break. Humans will be tested.”

He reached into the thick hair at his waist and pulled out a packet wrapped in broad leaves. He handed it to Herbert.

“Gift,” Kuronda said. “From my people to yours.”

Herbert opened the leaves. Inside were seeds. Dozens of them. Seeds of plants he did not know, varieties that had vanished from the catalogs, ancient strains that remembered how to grow without poison, without machines.

“We gather,” Kuronda explained. “We keep alive what humans destroy. Maybe someday, you need these again. Need food that grows in the hard times. Need medicine from the forest.”

Herbert wept. He held the future in his calloused hands.

“Thank you,” he whispered.

Kuronda placed a hand on Herbert’s shoulder. The weight was immense, grounding.

“One more thing,” the Giant said. “Tell the story. Maybe they do not believe the Giant. But tell them the truth. Tell them that technology cannot save you if you cannot love each other. Tell them that when the fire comes, the only water is community.”

He stood, a silhouette against the stars.

“We hope for you, Herbert Fletcher. Because if humans die, the world dies. We are one family.”

He melted into the trees, and the silence flowed back in, but it was no longer empty. It was full of promise.

Thirty years have passed since that night. Herbert Fletcher is an old man now, his skin like parchment, his hands trembling like dry leaves.

But the farm is green.

While the valley around him dried up and blew away, Herbert’s land became an oasis. The seeds Kuronda gave him grew into plants that defied the drought. The community he built became a fortress against the despair.

His grandchildren run the farm now. They do not use the great machines. They work with the land, not against it. They hold workshops in the barn, teaching the young how to grow, how to share, how to listen.

Herbert sits on the porch. He keeps a wooden box on his lap. Inside are the carvings he made—a man and a giant, standing side by side.

He tells the story to anyone who will listen. He tells them of the Watcher in the corn. He tells them of the Cliff. He tells them that the “bad times” are not coming—they are here.

But he also tells them of the hope.

“The Giant told me,” Herbert says, his voice raspy but strong, “that hope is like a seed in winter. It looks dead. It is small. But it knows the sun is coming.”

They say that if you walk the edge of the Fletcher farm at twilight, where the corn meets the ancient woods, you can feel a presence. It is not threatening. It is a heavy, warm feeling, like the gaze of a grandfather watching a child learn to walk.

They say the Watchers are still there. They are waiting to see if we will run off the cliff, or if we will finally, at the last moment, remember how to stop, how to listen, and how to turn back to one another.

And in the center of the farm, in a garden that never dies, the seeds of the Giant grow tall and strange and beautiful, a living testament to the night a monster taught a man how to be human.