Where Did the Nazi Gold Go After 1945?

In April 1945, deep inside a salt mine near the small German town of Merkers, U.S. troops forced open sealed steel doors and stepped into a scene few could have imagined. Before them lay stacks of gold bars, crates of foreign currency, bags of coins, and priceless jewels—an underground vault holding the financial core of the collapsing Third Reich. It was one of the largest treasure discoveries in history, and yet it answered only one question. The harder one followed immediately: who truly owned this gold, and what would become of it after the war?

The story of Nazi gold is not simply about hidden treasure. It is a tale of state theft, personal plunder, financial complicity, and an uneasy postwar reckoning that stretched on for decades.

The Systematic Theft of Europe’s Wealth

Nazi Germany’s accumulation of gold began well before the outbreak of World War II. When German forces annexed Austria in March 1938, officials wasted no time seizing the Austrian National Bank’s reserves. Roughly 100 metric tons of gold were transferred to Berlin, immediately strengthening the Reichsbank’s holdings.

A year later, after the occupation of Czechoslovakia, the pattern repeated. More than 26 tons of Czech gold were taken, much of it controversially transferred through accounts at the Bank of England—an episode that would provoke political debate long after the war. These seizures set a precedent: whenever German troops crossed borders, national treasuries were stripped.

As the war expanded, the Reichsbank, under the leadership of Walther Funk, became the central clearinghouse for looted wealth. Gold from Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece, and Yugoslavia was seized, melted down, and re-stamped to disguise its origins. By mid-war, Nazi Germany controlled hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of stolen bullion, much of it indistinguishable from legitimate reserves.

But state treasuries were only part of the story.

Gold Taken from Victims

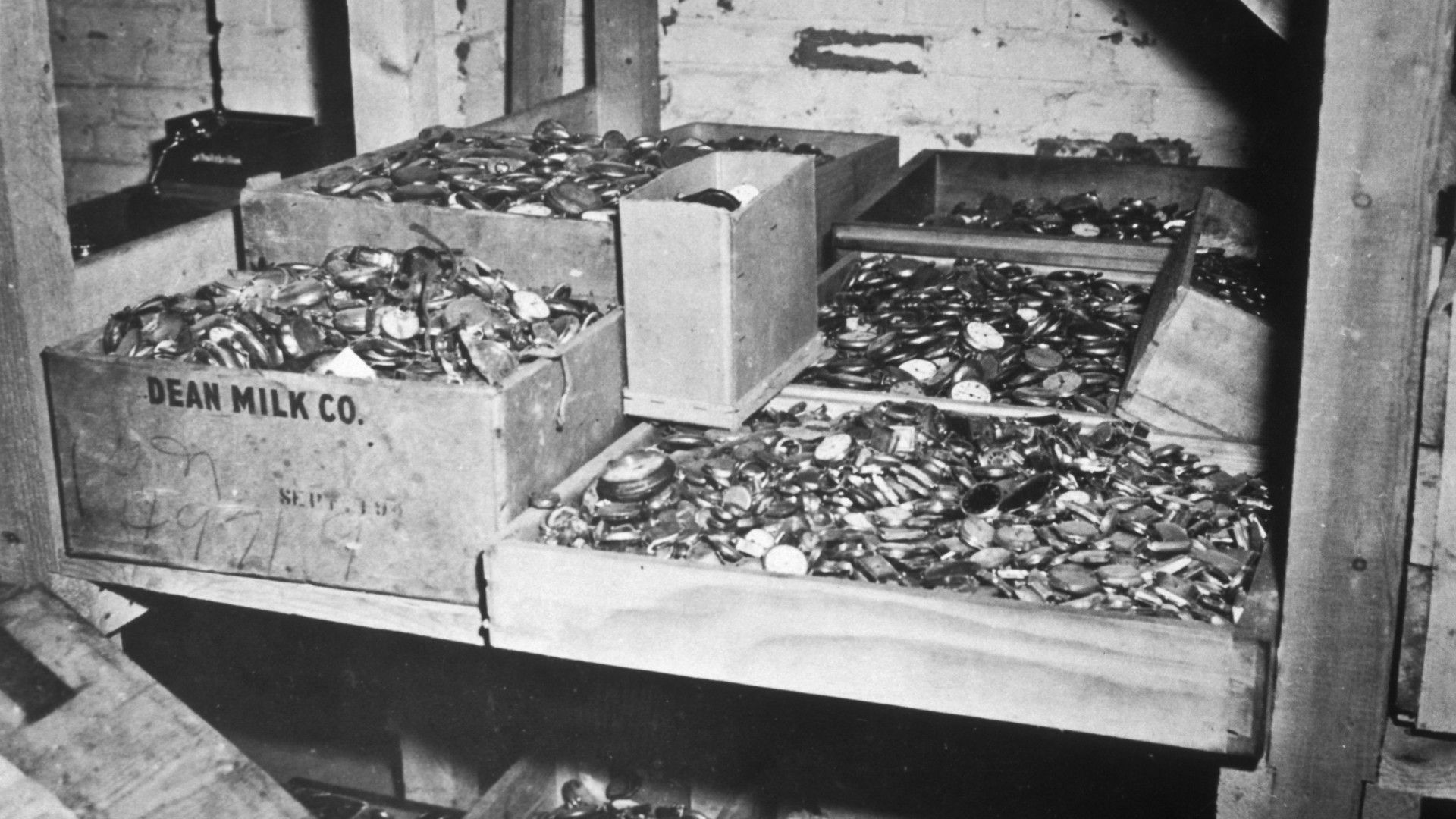

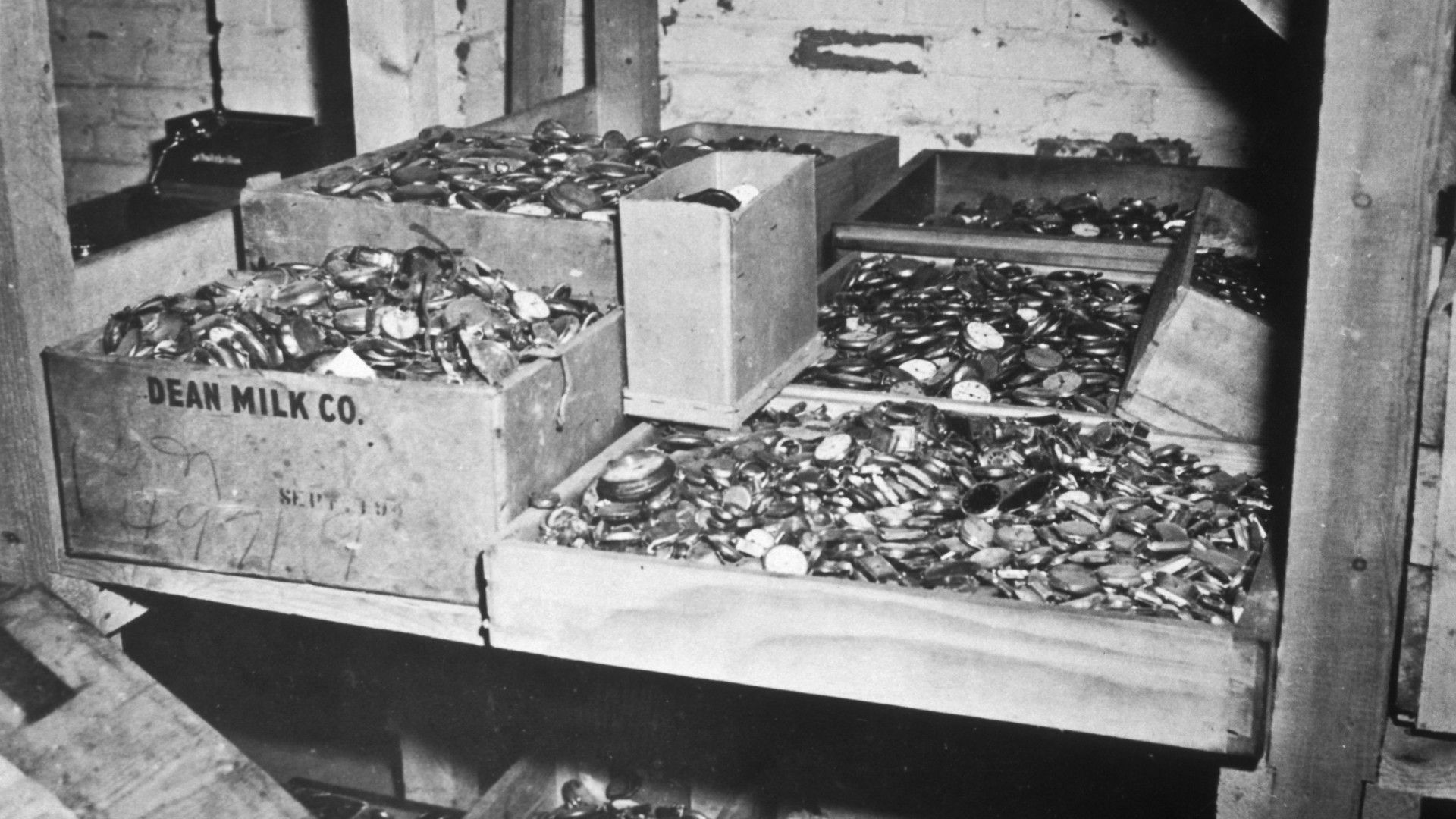

Beyond national reserves, the Nazi regime carried out one of history’s largest thefts of personal property. Jewish families deported to ghettos and concentration camps were stripped of valuables—rings, watches, coins, and jewelry. Even more chilling was the systematic collection of dental gold taken from murdered victims.

This gold, recorded meticulously in Reichsbank ledgers, was transported to Berlin in shipments known as “Melmer gold,” named after SS officer Bruno Melmer, who oversaw deliveries from the camps. Once melted down, it became indistinguishable from other bullion. Though precise totals are impossible to establish, postwar investigators confirmed that gold taken directly from victims was folded into Germany’s financial reserves.

By 1943, as Allied bombings intensified and defeat loomed, the Nazi leadership began moving gold out of Berlin. Neutral countries became essential to this process.

Neutral Banks and Financial Laundering

Switzerland played a central role in laundering Nazi gold. The Swiss National Bank accepted large quantities of Reichsbank gold, often without demanding proof of origin. Between 1939 and 1945, Swiss institutions received more than 300 million Swiss francs’ worth of looted bullion.

Portugal, Sweden, and Turkey also became part of the network. Portugal traded tungsten ore vital for German weapons production, Sweden supplied iron and ball bearings, and Turkey provided chrome ore essential for industry—often paid for with gold of questionable origin.

Allied governments protested, but economic neutrality and wartime profit often outweighed moral concerns. By the time Germany collapsed in 1945, Nazi gold was scattered across vaults, mines, banks, and hidden depots throughout Europe. Some had been smuggled abroad; some buried deep underground. Much of it was unaccounted for.

Allied Discoveries in 1945

As Allied forces advanced into Germany in the spring of 1945, they uncovered astonishing caches of looted treasure. The most famous discovery occurred on April 8, when U.S. Third Army units entered the Merkers salt mine in Thuringia. Inside were approximately 8,000 gold bars, crates of bullion, foreign currency, and artworks stolen from across Europe.

The find was politically sensitive. Merkers lay in a zone soon to be handed over to Soviet control. American commanders quickly removed the treasure, transferring it west under tight security. Photographs of Eisenhower, Patton, and Bradley inspecting the gold became iconic images of victory—and responsibility.

Other caches followed. Mines, bank vaults, and Alpine depots yielded more gold and cultural treasures. The interception of the Hungarian Gold Train in Austria revealed valuables looted from Hungarian Jews, including jewelry, silverware, and household items. Its chaotic handling later became one of the most controversial episodes of postwar restitution.

Yet not all treasure was recovered. As the Reich collapsed, SS units attempted to hide or destroy evidence. Convoys vanished, crates were dumped into rivers, and rumors spread of secret vaults and sunken hoards. Some stories were exaggerated, others entirely fabricated—but they reflected real gaps in the record.

The Question of Restitution

Recovering the gold was only the first step. Deciding what to do with it proved far more difficult.

In September 1946, the United States, Britain, and France established the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold, based in Brussels. Its mission was to redistribute recovered gold to the countries whose central banks had been plundered.

Because the gold had been melted and mixed, tracing individual bars to specific nations was impossible. Instead, the Commission adopted a proportional system: recovered bullion was pooled and distributed based on documented losses. On average, countries recovered only about 65 percent of their stolen reserves.

For states, the process was imperfect but functional. For individual victims, it was devastating.

Personal property—jewelry, household items, and gold taken from concentration camp victims—largely fell outside the Commission’s mandate. Many governments absorbed these losses into national settlements. Survivors and heirs often received nothing.

As Cold War priorities took precedence, pressure for individual restitution faded. Justice, for many victims, was postponed indefinitely.

Renewed Scrutiny and Late Reckoning

The issue of Nazi gold resurfaced dramatically in the 1990s. Investigations into dormant Swiss bank accounts belonging to Holocaust victims reignited global scrutiny. Neutral countries were accused of profiting from Nazi crimes and concealing wartime transactions.

In 1997, representatives from 41 nations gathered at the London Conference on Nazi Gold. Remaining reserves held by the Tripartite Commission—about 5.5 metric tons—were earmarked for Holocaust survivor assistance programs. In 1998, more than fifty years after its creation, the Commission was formally dissolved.

For many survivors, the gestures came too late and fell far short of meaningful restitution.

Unresolved Mysteries and Enduring Myths

Despite decades of investigation, not all Nazi gold has been accounted for. Legends persist of hidden trains, Alpine lakes, and overseas vaults. Most claims have been debunked, but the fascination endures.

What remains unresolved is not only the fate of missing bullion, but the moral legacy of how recovered wealth was handled. Much of the gold went to states, not to the individuals from whom it was stolen. Financial systems that enabled laundering faced limited consequences for decades.

Today, Nazi gold has become more than a material question. It symbolizes industrialized theft, bureaucratic cruelty, and the long shadow of unfinished justice. Each rediscovered ledger or reopened archive reminds the world that the consequences of plunder do not end when wars do.

The gold may be mostly gone—but the reckoning it represents is still unfinished.