Why Coca-Cola Created Fanta in Nazi Germany: From American Icon to Moral Compromise

In 1941, as the United States formally entered World War II and declared war on Nazi Germany, Coca-Cola faced a dilemma that would permanently shape its global legacy. Should an American company abandon a profitable foreign market now ruled by a dictatorship, or attempt to survive by adapting to a regime increasingly defined by repression, war, and mass violence?

While American soldiers prepared to fight Nazi Germany on the battlefield, Coca-Cola’s German subsidiary was not shrinking—it was thriving. At the center of this paradox stood Max Keith, the head of Coca-Cola GmbH, who engineered one of the most controversial survival strategies in corporate history. That strategy would eventually give birth to Fanta, a drink created not in postwar prosperity, but under wartime scarcity and moral compromise.

Coca-Cola’s Early Success in Germany

Coca-Cola entered Germany in the late 1920s and initially struggled. In 1929, sales totaled just 6,000 cases. But the early 1930s brought dramatic change. As the Nazi Party rose to power in 1933, Coca-Cola’s fortunes rose with it. By that year, sales had surged past 100,000 cases, a staggering increase that coincided almost perfectly with Adolf Hitler’s ascent.

For Coca-Cola executives in Atlanta, Germany represented opportunity at a time when the Great Depression had devastated American markets. Walking away from a fast-growing consumer base was unthinkable. Instead, the company doubled down and placed its German operations under the leadership of Max Keith, a fluent German speaker and skilled political operator who understood how to navigate authoritarian systems.

Keith was not a member of the Nazi Party, but he was deeply pragmatic. His guiding principle was simple: survival and growth at any cost.

Aligning with the Nazi State

Under Keith’s leadership, Coca-Cola Germany increasingly aligned itself with Nazi economic and cultural priorities. Advertising was carefully crafted to portray Coca-Cola not as an American luxury, but as a drink for the German worker. One of Keith’s earliest marketing campaigns was tellingly named “Blitzkrieg,” a rapid and aggressive push into the German beverage market that targeted beer drinkers and working-class consumers.

Visibility mattered in Nazi Germany, and Keith ensured Coca-Cola had plenty of it. The brand appeared at Party rallies, including the massive Nuremberg gatherings, with kiosks and billboards placed alongside official symbols of the regime. Coca-Cola’s red-and-white logo became a familiar sight at events meant to project unity and strength.

This public alignment deepened during the 1936 Berlin Olympics. As the Nazi government sought to present a sanitized image of Germany to the world, Coca-Cola embraced the moment. Its branding appeared prominently throughout Olympic venues, visually linking the American soft drink to one of the regime’s most important propaganda events.

Crossing Ethical Lines

As Coca-Cola Germany’s success grew, so did political scrutiny. At one point, Nazi officials began circulating rumors that Coca-Cola was Jewish-owned—a dangerous accusation in a state defined by antisemitic policy. Such rumors threatened boycotts, vandalism, or forced seizure.

Keith’s response marked one of the clearest moral failures in the company’s history. Instead of issuing a neutral denial, he placed an advertisement in Der Stürmer, one of the most virulently antisemitic newspapers in Germany. The ad explicitly denied any Jewish ownership, indirectly reinforcing the publication’s hateful ideology.

This was not passive accommodation. It was active financial support of propaganda that normalized discrimination and violence. By the mid-1930s, Coca-Cola Germany’s explosive growth—sales had risen more than 17,000 percent since 1929—had created a corporate culture where ethical boundaries steadily eroded.

War, Expansion, and Deeper Entanglement

As war approached, Keith’s cooperation intensified. In 1938, during the Nazi annexation of Austria, Coca-Cola Germany’s annual convention featured banners adorned with swastikas. The meeting ended not just with a pledge to the brand, but with a mass “Sieg Heil” to Hitler.

By 1939, Keith openly praised Hitler’s leadership at company events, effectively merging Coca-Cola Germany’s corporate identity with the ideology of the state. The rewards followed quickly. As German forces occupied neighboring countries, Keith was appointed to the Office of Enemy Property, granting him authority over soft drink production across occupied Europe.

Through military conquest, Coca-Cola Germany absorbed facilities in France, the Netherlands, and beyond. Each territorial expansion became a business expansion. While American troops fought the regime, Coca-Cola GmbH profited from it, becoming a fully integrated component of the Nazi economic system.

The Crisis of 1941

Everything changed in December 1941. After Pearl Harbor, Germany declared war on the United States. Overnight, Coca-Cola Germany was cut off from its parent company. Shipments of the secret Coca-Cola syrup from Atlanta stopped. The company faced the real possibility of seizure as enemy property.

For Keith, survival required reinvention.

Without access to Coca-Cola’s core ingredients, Keith ordered his chemists to create an entirely new beverage using only what wartime Germany could provide. The result was a drink made from apple fiber waste, whey from cheese production, beet sugar, and leftover fruit scraps. It was cloudy, brown, and nothing like Coca-Cola.

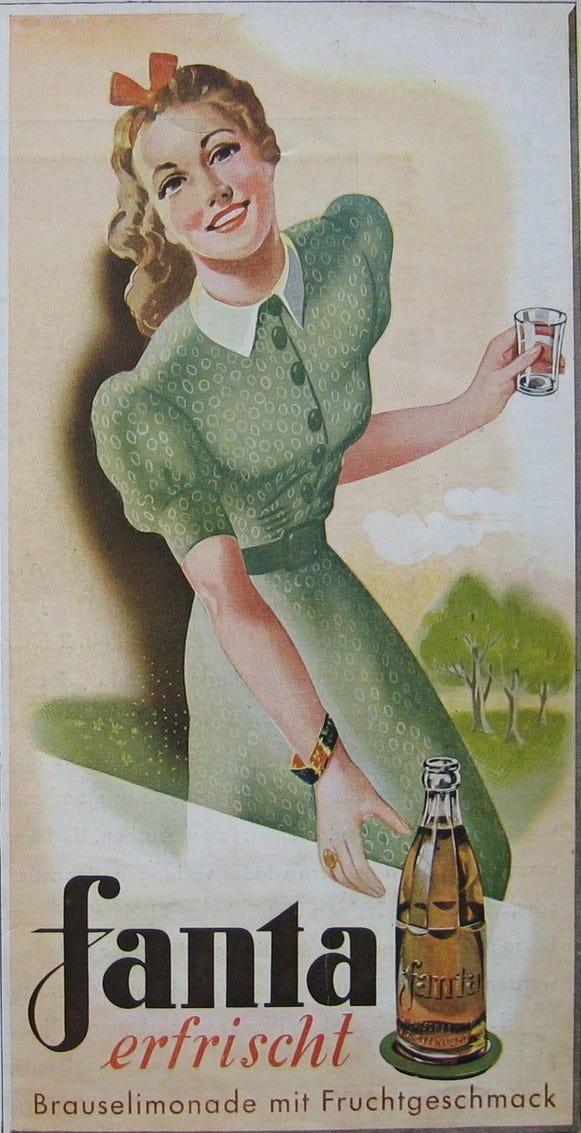

During a tense naming meeting, Keith urged his staff to use their Fantasie. One salesman suggested “Fanta.” The name stuck.

Fanta’s Wartime Success

Fanta was an immediate success. By 1943, it sold roughly three million cases annually. In a rationed economy desperate for sweetness, Fanta became a kitchen staple, often used in cooking rather than drunk on its own.

Crucially, Fanta received exemptions from wartime rationing, giving it a significant advantage over competitors. Coca-Cola Germany continued operating with access to resources that might otherwise have gone to the war effort.

Behind the scenes, ethical compromises deepened further. Historical evidence suggests that Coca-Cola Germany benefited from forced labor, like many companies operating within the Nazi industrial system. While definitive documentation remains incomplete, the pattern aligns with broader wartime practices.

After the War: No Consequences

When Allied forces closed in on Germany in 1945, Max Keith sent a short telegram to Atlanta: “Coca-Cola GmbH still functioning. Send auditors.”

The message revealed his priorities. And the response from Coca-Cola’s leadership was telling.

Keith faced no punishment. Instead, he was rewarded. After the war, Coca-Cola appointed him head of Coca-Cola Europe, praising him for preserving company assets during wartime chaos. Fanta, stripped of its origins, was rebranded and eventually became a global success worth billions.

Legacy and Unanswered Questions

Fanta’s origin story is often told as an example of ingenuity under pressure. But stripped of marketing gloss, it is also a case study in how corporations adapt to authoritarian regimes—and how profit can outweigh principle.

Coca-Cola did not create Nazi ideology. But through accommodation, promotion, and cooperation, its German subsidiary became embedded in one of history’s most destructive systems. The company survived. The brand flourished. Accountability, however, was minimal.

Fanta’s legacy forces an uncomfortable question that still echoes in boardrooms today: what is the true cost of doing business under dictatorship—and who pays it?