By the final years of World War II, hunger had become a weapon in Europe. Across Germany, cities lay broken and supply lines collapsed. Families survived on ration cards that offered less each month. In some neighborhoods, meals were improvised from whatever could be found. Thin soups boiled roots, bread stretched far beyond its limits.

The promises of abundance made by the Nazi state had dissolved into daily scarcity. Yet thousands of miles away, a different reality existed. One that many German soldiers refused to believe. Between 1942 and 1945, hundreds of thousands of German prisoners of war were transported across the Atlantic to the United States.

They came from North Africa, Italy, France, and eventually Normandy. Most expected harsh treatment. Many believed American shortages were as severe as those at home. They were wrong. The first surprise came before they ever reached land. Aboard transport ships, German prisoners were served regular meals, hot food, fresh bread, vegetables, and meat.

For men accustomed to field rations or starvation diets, the portions felt unreal. Some assumed it was temporary. Others suspected deception. But when the ships docked and the prisoners were moved inland, the pattern continued. Across the American heartland, prisoner of war camps were established in rural areas, Kansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Alabama, Minnesota.

These camps followed the Geneva Convention closely. Prisoners received the same caloric intake as American garrison troops, often far more than civilians in wartime Europe. In camps like Concordia, Kansas, and Aliceville, Alabama, German prisoners lined up for meals that defied belief. thick slices of meat, real coffee, unlimited bread, fresh vegetables, food served consistently without ceremony, without shortage.

At first, many dismissed it as a trick. Some joked quietly that the Americans were fattening them for some unknown purpose. Others waited for the portions to shrink. They never did. Weeks passed. Then months, men who had arrived Gaunt began to regain weight. Medical logs later showed dramatic improvements in health.

For some, it was the first time in years they felt physically secure. The abundance extended beyond the camps themselves. German prisoners were assigned to farm labor across the country, helping harvest crops and 10 livestock while American manpower was deployed overseas. Working under supervision, they saw the scale of American agriculture firsthand.

Fields stretching to the horizon, mechanized equipment, storage facilities filled to capacity. What shocked them most was not just that food existed, but that there was more than enough. In many camps, food waste was common. Leftovers were discarded. Spoiled produce was replaced without hesitation.

For men who had watched scraps fought over back home, this was almost disturbing. Some wrote home in censored letters, struggling to describe what they were seeing without sounding unbelievable. As the war drew to a close, trust slowly increased. Select prisoners were granted supervised work details in nearby towns.

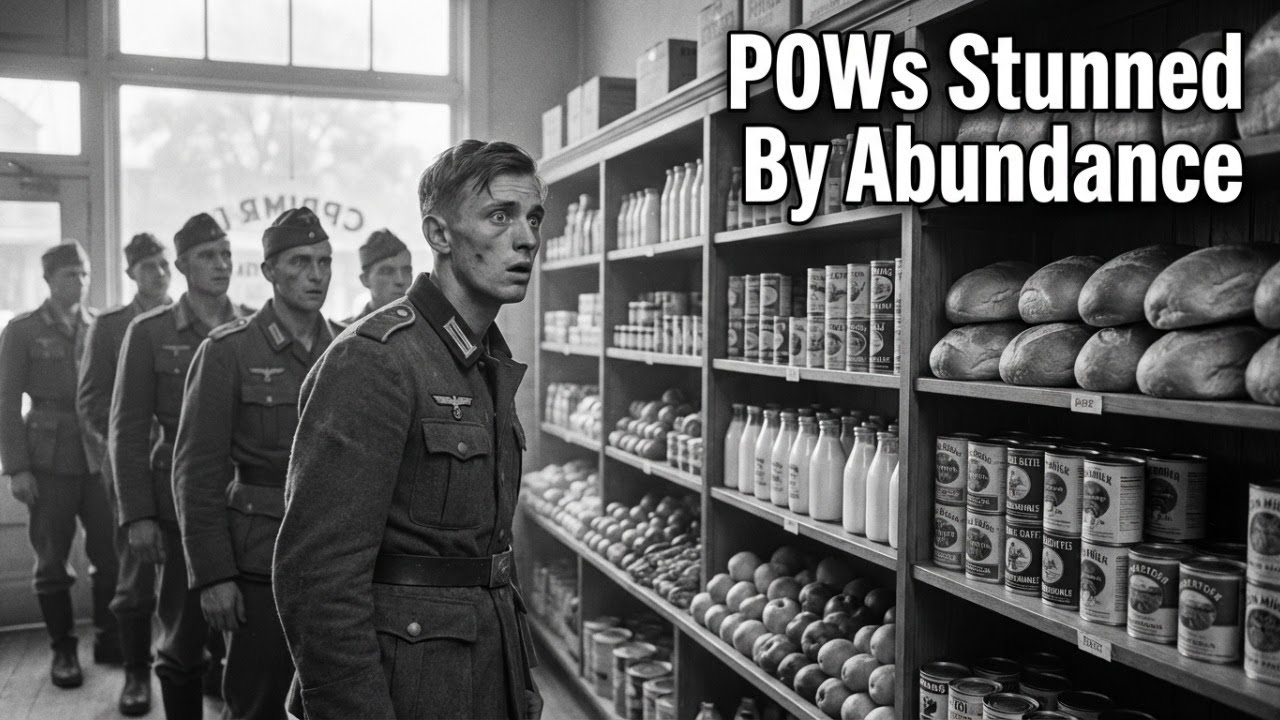

Others were allowed brief excursions under the honor system. For many, these moments would leave the deepest impression. Small town America did not look like a nation at war. Grocery stores were stocked wallto-wall, fruits from distant regions, butter without rationing, meat counters filled daily, no armed guards, no ration cards, no urgency.

At first the prisoners laughed. Surely this was staged. A performance meant to break morale. Then they noticed something impossible to fake. The locals shopped calmly. Children wandered the aisles. Clerks chatted casually. No one acted as if the food might disappear tomorrow. Silence replaced skepticism. For men raised on years of propaganda describing America as decadent and fragile.

The contradiction was overwhelming. This was not weakness. This was capacity. a nation able to fight a global war and still feed both its citizens and its enemies. Back in Germany, letters from home spoke of hunger growing worse, of cities reduced to rubble, of children undernourished. The contrast became impossible to ignore.

For many prisoners, ideology did not collapse all at once. It eroded quietly. Doubt replaced certainty. Questions replaced slogans. Some prisoners would later say that the first cracks in their belief system did not come from defeat on the battlefield, but from standing in front of a full grocery shelf.

When repatriation began in 1945, many German PS returned home changed. They carried memories that did not align with what they had been taught. Memories of full plates, open markets, and a system that produced abundance rather than scarcity. In the years that followed, as Europe rebuilt and alliances shifted, those memories mattered.

They shaped attitudes toward democracy, toward cooperation, toward the idea that power could come from production rather than control. The story of German prisoners in America is not just about captivity. It is about contrast. About how a war built on conquest failed to feed its people, while a nation fighting far from home managed to sustain even its enemies.

In the end, the shelves told a story louder than any speech. And for many who saw them, nothing was ever the same again.