“They Are Not Monsters”: How a Plate of Bacon and Eggs and a Texas Thanksgiving Shattered the Worldview of German Female POWs

CAMP FLORENCE, TEXAS — The Texas heat in June 1945 was a physical weight, a suffocating blanket that pressed down on the dusty plains 40 miles outside San Antonio. For the 12 women standing barefoot on the dirt, however, the heat was the least of their worries. They were German prisoners of war, transported halfway across the world to a land they had been taught was inhabited by gangsters and savages.

Dressed in shapeless gray cotton uniforms, they stood in silence, waiting for the cruelty they had been promised. They were a mix of nurses, communication specialists, and conscripted auxiliaries, stripped of their rank and dignity.

Elsa Hoffman, a 32-year-old widow from Hamburg, watched the American guards with terrified eyes. She expected interrogation. She expected starvation rations. She expected to be treated as a monster.

What she got instead was a breakfast that would dismantle her entire belief system.

The Propaganda Lie

To understand the shock that awaited these women, one must understand the world they came from. For years, the Nazi regime had fed its people a steady diet of fear. They were told that Americans were brutal, that prisoners were tortured, and that surrender was a fate worse than death.

“Don’t trust it,” whispered Freda Bauer, a 43-year-old former schoolteacher whose face was etched with the hard lines of war. “Kindness can be tactical. Wait and see what they want from us.”

They had arrived at Camp Florence three days prior, dazed from a five-day train journey across the vast, untouched American landscape. They had seen endless fields of wheat, tidy white houses, and children waving at the train—images of prosperity that contrasted sharply with the rubble and ruin of the Germany they had left behind.

But even the peaceful scenery couldn’t erase the fear. As they marched toward the mess hall that first morning, the air was thick with the scent of frying meat.

“It smells like bacon,” young Anna Schmidt whispered, her 19-year-old eyes widening. “Actual bacon.”

The Breakfast That Changed Everything

Inside the wooden mess hall, the scene was chaotic but cheerful. American soldiers stood behind serving counters, grinning as if feeding prisoners was the best job in the army. When Elsa reached the front of the line, a young soldier placed a tray in her trembling hands.

It wasn’t watery gruel. It wasn’t stale bread mixed with sawdust.

It was two fried eggs, yolks bright and perfect. It was three strips of crispy, glistening bacon. It was a mound of golden hash browns, buttered toast, and a cup of cold orange juice.

Elsa stared at the plate, her mind unable to process the abundance. Behind her, she heard a gasp from Margarite Vogel, a nurse from Munich.

They sat at their table, staring at the food as if it were an alien artifact.

“It’s a trick,” Freda insisted, though her voice wavered. “They’ll take it away. Or it’s poisoned.”

But at the tables around them, male German prisoners—sunburned, healthy, and loud—were eating the same meal without hesitation.

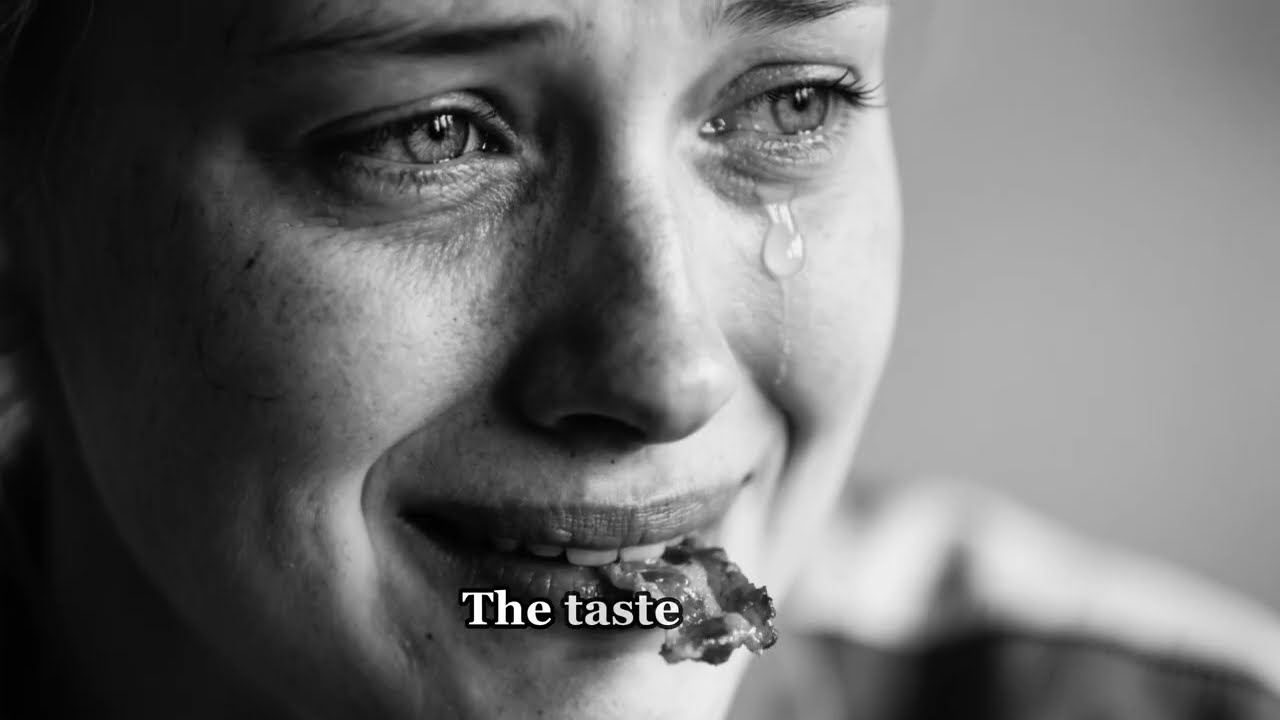

Anna was the first to break. She picked up a strip of bacon with her fingers, holding it like a sacred relic. She took a bite, and then, she began to weep.

It wasn’t a sob of despair, but of release. The salty, fatty taste of the bacon was undeniable proof that the world was not ending. It was proof that hunger was not permanent.

“It’s real,” Anna whispered through her tears. “It’s actual bacon.”

Elsa cut into her egg, watching the golden yolk spill across the plate. She took a bite and felt a wall inside her crumble. This was not the behavior of monsters. This was the behavior of people who had so much that they could afford to be generous to their enemies.

The Humanization of the Enemy

That breakfast was the first crack in the dam. Over the coming months, the floodwaters of kindness would wash away years of indoctrination.

The women were assigned to kitchen duty, working alongside American soldiers who treated them not as captives, but as coworkers. Elsa found herself paired with Corporal Jimmy Barnes, a 22-year-old redhead from Oklahoma who had a laugh that filled the room.

There were no interrogations. Instead, Jimmy taught her English words while they peeled potatoes. “Potato. Knife. Stove. Careful, that’s hot.”

One afternoon, he showed her a creased photograph of a smiling girl. “My wife, Sarah,” he said, his voice thick with longing.

In return, Elsa showed him the only treasure she had left: a photo of her six-year-old daughter, Greta, who was surviving in the ruins of Hamburg.

“She’s beautiful,” Jimmy said, studying the photo with genuine care. “War is hard on families.”

It was a simple sentence, but it bridged the gap between them. They were no longer victor and vanquished; they were just two parents missing the people they loved.

The transformation continued. Sergeant Willis, the head cook, took Margarite under his wing, teaching her how to fry chicken and make biscuits from scratch. “After the war, you could open a restaurant,” he told her. “People will always need good cooks.”

Even stoic Freda softened when she was assigned to the bakery, learning the chemistry of yeast from a quiet man from Minnesota. “In Germany, I taught children,” she told him. “Now I teach bread to rise.”

“Both are good work,” he replied. “Both involve patience and hope.”

A Birthday to Remember

The cultural barriers fell completely on Anna’s 20th birthday. It was supposed to be just another day of imprisonment, but when the women entered the mess hall for dinner, they found their table decorated with red, white, and blue crepe paper.

Sergeant Willis marched out carrying a cake—a real cake with white frosting and candles.

“Happy Birthday, Anna,” the sign read in careful German.

Anna froze, her hands flying to her mouth. The American soldiers began to sing “Happy Birthday,” and the German male prisoners joined in. The languages mixed in a chaotic, beautiful harmony.

They ate cake. They drank punch. They danced to harmonica music. For a few hours, the wire fences and guard towers disappeared. There was only music, laughter, and the realization that enemies are just people you haven’t danced with yet.

“They shouldn’t have done that,” Freda said later that night, looking at the small gifts Anna had received—a carved wooden bird, an embroidered handkerchief, a bar of soap. “We’re enemies. They should hate us.”

“But they don’t,” Margarite whispered. “And I don’t know what to do with that.”

The Thanksgiving Miracle

The ultimate test of this new reality came in November. The women were working on a local ranch owned by Thomas and Dorothy Garrett, an elderly couple who treated the prisoners like farmhands rather than threats.

When Thanksgiving arrived, Dorothy did something that defied all logic: she invited the German prisoners to dinner.

“We can’t come,” Elsa protested. “We’re prisoners.”

“Already cleared it with the commander,” Dorothy replied. “Thanksgiving is about gratitude. Seemed right to include folks who’ve had a hard year.”

And so, twelve German women sat at a long table in a Texas farmhouse, surrounded by the smell of roast turkey, pumpkin pie, and cornbread. Before they ate, Thomas Garrett stood at the head of the table and bowed his head.

“Lord, we thank you for this food, and for the peace that’s finally come,” he prayed. “We thank you for these guests who have traveled far and suffered much. Help us remember that we are all your children, regardless of what uniforms we wore.”

Elsa looked around the table. She saw American farmers and German prisoners, heads bowed together. She realized then that the war was truly over—not because treaties were signed, but because regular people had decided to stop hating each other.

The Return and the Legacy

In January 1946, the orders came. The prisoners were to be repatriated to Germany. Leaving Camp Florence was bittersweet. They were going home to ruins, leaving behind a place of abundance and safety.

On their final morning, Sergeant Willis made a farewell feast of pancakes and sausage. Jimmy Barnes gave each woman a small American flag. “Remember that we’re all just people trying to get by,” he told them.

Elsa returned to Hamburg to find a city of ghosts. Her neighborhood was gone, but she found her mother and daughter living in a basement room. That night, over a soup made from American care packages, Elsa told them the story of the bacon and eggs.

“We have to rebuild,” she told her mother. “Not just buildings, but how we think. How we treat people.”

The Letter

Twenty years later, in 1965, an elderly Thomas Garrett sat on his porch in Texas. A letter arrived with German stamps.

It was from Elsa. She wrote to express her condolences on the passing of his wife, Dorothy, and to tell him about the life she had built. She ran a restaurant now, serving American and German food.

“I write now because I want you to know what that Thanksgiving dinner meant,” the letter read. “Not just the food, though God knows we needed it, but the acknowledgment that we were still human beings. Thank you for showing me that mercy wasn’t weakness, but the highest form of strength.”

Thomas folded the letter, tears in his eyes. He thought about the bacon, the eggs, the cookies, and the prayers. He realized that the true victory of the war hadn’t been won on the battlefield, but in the kitchens and dining rooms where enemies became neighbors.

The war had ended two decades ago, but the peace—the real peace—was still being built, one letter, one meal, and one act of kindness at a time.