Dean Martin just turned off the lights. Not dimmed them, not signaled the lighting guy. He walked off stage, found the main power switch, and flipped it. The entire ballroom packed with 350 guests who’d paid $100 ahead in 1965. Money went pitch black. When the emergency lights flickered on 30 seconds later, Dean was standing at the microphone. Sammy Davis Jr.

was behind him, still shaking. Frank Sinatra was frozen at the piano, his cigarette burning forgotten in the ashtray. Dean’s voice came through the speakers, quiet, calm. The same voice he used to sing That’s Amore. But the words weren’t amore. They were ice cold. Shows over, Dean said. What happened next made Dean Martin a hero to some and a traitor to others.

But it proved one thing beyond any doubt. Dean Martin didn’t compromise. Not for money, not for comfort, and definitely not for racism. This is the story of the night Dean Martin chose his friend over everything else. And somehow it made both stronger. March 17th, 1965. The Sands Hotel wasn’t the venue. That’s the story people remember, but it’s not quite accurate.

The real location was a private supper club in Kentucky. One of those exclusive establishments that booked major acts to prove they were sophisticated while maintaining rules that proved they absolutely were not. The Rat Pack was in the middle of a southern tour. Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr.

, Joey Bishop, and Peter Lofford. Five men who’d revolutionized entertainment and redefined what it meant to be cool in America. They commanded $100,000 per show in 1965, equivalent to nearly a million today. Venues begged for them, sold out in hours, standing room only. But there was always a tension when the Rat Pack performed in certain parts of the country because Sammy Davis Jr.

was black. And in 1965, even the most progressive venues in the South had rules. Sammy could perform. Sammy could make them laugh. Sammy could sing and dance and do impressions that left audiences breathless. But Sammy couldn’t use the front entrance, couldn’t eat in the main dining room, couldn’t stay in the hotel attached to the venue.

Sammy had learned to navigate this. He had to. It was the price of working in America in 1965. He’d smile, use the service entrance, laugh off the indignities, and deliver a performance so brilliant that people forgot or pretended to forget the rules they just enforced. Frank Sinatra hated it. Frank had been fighting against segregated venues since the 1940s.

He’d threatened to cancel shows, demand equal treatment for Sammy, make public statements about civil rights. Frank’s anger was famous, volcanic, impossible to ignore. Dean’s approach was different. Dean didn’t make speeches, didn’t threaten, didn’t announce his principles. He just watched and remembered, and when the moment came, he acted with a finality that made Frank’s anger look like posturing.

The night started well enough. The crowd was wealthy, dressed in their finest, eager to see Frank Sinatra and his legendary friends. The room was beautiful. Crystal chandeliers, white tablecloths, waiters and tuxedos. The kind of place that wanted to be seen as cultured, worldly, above the ugliness of segregation.

But Dean had noticed things. The way the venue owner avoided looking at Sammy during the sound check. The way Sammy had been directed to a separate dressing room, not with the other performers, but near the kitchen. the way none of the white waiters spoke to him directly. Dean didn’t say anything.

He just lit a cigarette, poured himself a scotch, and made a mental note. This was Dean’s method. He didn’t confront problems headon like Frank. He filed them away, waited, let people reveal who they really were. The show began at 900 p.m. sharp. Frank opened with Luck Be a Lady. The crowd loved it. Then Dean sauntered on stage, drink in hand, and did his charming drunk routine.

The carefully crafted persona that made him seem like he’d just stumbled in from the bar. When in reality, he was completely sober and in total control. Sammy came on for his segment. He was brilliant as always. He sang, “I’ve got you under my skin.” He did impressions, Frank, Dean, even President Johnson. He tapdanced.

The audience applauded, some enthusiastically, some politely, some not at all. Dean watched from stage left, leaning against the piano, seemingly half asleep, but he was paying attention. He always was. He noticed which tables weren’t clapping for Sammy, which faces showed discomfort rather than enjoyment, which people had come to see the colored boy perform, as if Sammy were a trained seal rather than one of the greatest entertainers alive.

20 minutes into the show, it happened. Sammy had just finished The Candyman. The song wouldn’t become his signature for another few years, but he was testing it out, seeing how audiences responded. He ended with a flourish, a spin and a smile, arms spread wide. The applause was solid but not overwhelming. And then from somewhere in the third row, a voice cut through the polite clapping.

One word, loud enough for the whole room to hear. A word we don’t need to repeat. A word designed to remind Sammy Davis Jr. that no matter how talented he was, no matter how famous, no matter how many people paid to see him, there were still those who saw him as less than human. The room went silent. Not the good kind of silence, not the anticipatory pause before a punchline.

This was the terrible silence that comes when everyone knows a line has been crossed, but no one is sure what happens next. Sammmy smile froze. His arms slowly lowered to his sides. For just a moment, maybe three seconds, but it felt like an hour. Sammy Davis Jr., the man who could do anything on a stage, didn’t know what to do. Frank Sinatra’s head snapped toward the audience like a predator spotting prey.

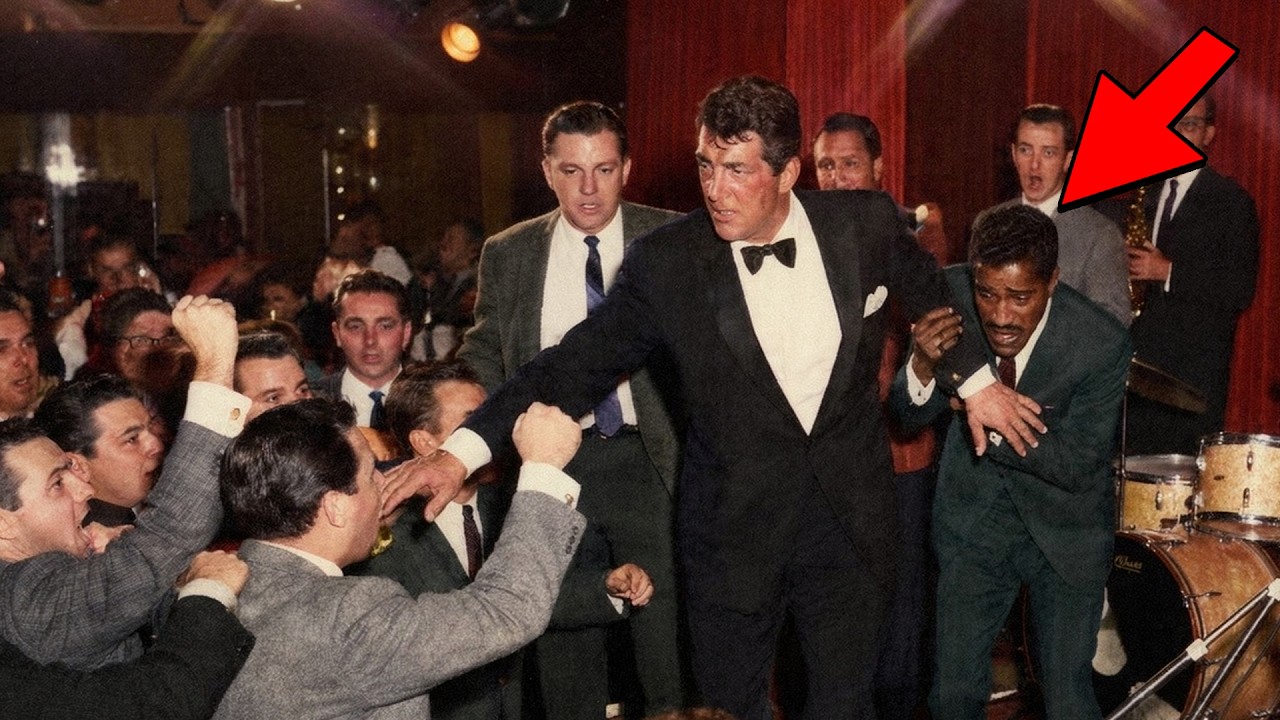

His face went red. He stood up from the piano bench. Frank was about to explode, about to unleash the full force of his legendary temper on this crowd, this venue, this entire backward corner of America. But before Frank could say a word, Dean Martin moved. Dean set down his drink carefully, deliberately.

The glass made a soft clink against the piano top that somehow seemed louder than the slur that had just been shouted. He didn’t look angry. Dean Martin never looked angry. His face showed the same mild amusement it always did, as if he just heard a mediocre joke and was considering whether to laugh politely.

He walked toward Sammy, not quickly, not dramatically, just that same loose, easy walk he always had, like he was heading to the bar to refresh his drink, like nothing unusual was happening. The audience held its breath. What was he going to do? Was he going to make a speech? defend Sammy. Call out the heckler. Dean put his hand on Samm<unk>s shoulder, gave it a gentle squeeze.

Then he leaned in and whispered something in Samm<unk>s ear that no one else could hear. Years later, Sammy would reveal what Dean said in that moment. “Don’t worry, I’m ending this.” Dean straightened up. He looked out at the audience with those sleepy, half-litted eyes that had charmed millions. He took a long drag from his cigarette.

The smoke curled up toward the chandeliers. Then he walked off stage, not to the wings, not to his dressing room. He walked directly to the back wall where the electrical panel was located. Frank watched, confused. The audience stirred nervously. Sammy stood frozen at center stage. Dean found the main circuit breaker.

He looked at it for a moment, as if considering the implications of what he was about to do. Then he flipped it. The entire ballroom went black. Darkness. Complete darkness. 350 people sitting in expensive clothes, holding expensive drinks in an expensive venue. Suddenly unable to see their own hands. Confused murmuring.

Nervous laughter. Someone dropped a glass. A woman gasped. The darkness lasted exactly 32 seconds. Long enough to make everyone uncomfortable. long enough to make the point. Then the emergency lights kicked in, dim, yellow, unflattering. The room looked suddenly cheap. The crystal chandeliers were just glass. The white tablecloths had stains.

The wealthy patrons looked old and tired. Dean walked back on stage. He didn’t hurry. He walked to the microphone, picked it up, and stood there for a moment, looking out at the crowd. His face was perfectly calm. He could have been about to sing. Everybody loves somebody. Show’s over, Dean said. His voice was quiet, conversational, the same tone he used for everything, but it carried an absolute finality.

You paid to see us perform, and we were happy to perform, but apparently some of you paid to do something else. So, here’s what’s going to happen, he gestured to Frank and Sammy. We’re leaving right now. The venue will refund your money or not. I don’t really care. Someone in the audience stood up. You can’t just leave.

We have a contract. Dean looked at the man, looked at him with that same mild, amused expression. Sue me, he said simply. Then he turned to the venue owner who had appeared at the side of the stage, his face pale with panic. You wanted the rat pack. This is the rat pack. All of us together or none of us. You don’t get to enjoy Sammy’s talent and then treat him like he’s less than human.

So, you can have your room back and your rules and your customers who think it’s acceptable to shout that word. But you can’t have us. Frank Sinatra was smiling now. That dangerous smile he got when Dean had done something Frank had wanted to do but hadn’t thought of. Dean turned to Sammy. “Come on,” he said. “Let’s go get a real drink.

” They walked off the stage together. Dean, Frank, and Sammy. Three men who’d built their careers on being cool, being smooth, being above the chaos. And in that moment, they were exactly that. The audience sat in stunned silence. Some were outraged. They’d paid good money, after all. Some were embarrassed, looking around to see who had shouted that word.

Some were quietly relieved that someone had finally said what needed to be said. The venue owner chased after them backstage. You can’t do this. I’ll sue. I’ll make sure you never work in this state again. Dean didn’t even turn around. Frank did though. And Frank’s response was succinct. Pal.

We don’t want to work in your state. That’s kind of the whole point. They got in their car, a chartered limousine that was supposed to take them to the next venue, and told the driver to just drive anywhere away from there. For the first few minutes, no one spoke. Then Sammy, who’d been staring out the window, said quietly, “You didn’t have to do that, Dean.

” Dean lit another cigarette. “Yeah, I did. That’s probably $50,000 you just walked away from.” Dean shrugged. “I spend more than that on golf.” Then more seriously, Sam, I don’t care how much money they have. I don’t care how important they think they are. Nobody talks to my friend that way. End of story. Frank, sitting in the front seat, turned around.

You know what kills me? He said, “I’ve been making speeches about this crap for 20 years, writing letters, threatening to cancel shows, and you just turn off the lights and walk out. That’s it. Show over.” Dean smiled. Frank, you’re the conscience. I’m just the guy who leaves when the party gets ugly. The story hit the newspapers within 24 hours.

Rat Pack walks out on soldout show. Depending on which paper you read, Dean Martin was either a hero standing up for civil rights or a spoiled celebrity who couldn’t handle a single heckler. The venue sued for breach of contract. The Rat Pack counters sued for creating a hostile work environment. Eventually, both parties settled quietly.

The venue didn’t want the publicity, and the Rat Pack had made their point. But the real impact wasn’t legal. It was cultural. Other performers started doing the same thing. When faced with segregated audiences or racist treatment of their fellow performers, they walked. They stopped accepting the money. They stopped making excuses.

And they all credited Dean Martin with showing them how. Not with a speech, not with anger, just with a simple decision. When the environment is wrong, you leave. You don’t argue. You don’t negotiate. You just leave. Years later, in 1978, a journalist asked Dean about that night. The civil rights movement had transformed America.

Segregation was illegal. The world had changed. “Do you regret walking out?” the journalist asked. That was a lot of money. Dean thought about it for a moment, taking a sip of his drink. Then he smiled. I regret that I didn’t turn the lights off sooner. The journalist pushed. But it was just one person who said that word. The whole audience wasn’t.

One person, Dean interrupted, his voice still quiet, but now with an edge. One person said it, and 349 people sat there and let him. That’s the same thing as 350 people saying it. He stubbed out his cigarette. Look, I’m not a politician. I’m not a civil rights leader. I’m just a singer who got lucky. But I know what friendship means.

And I know that if you’re my friend, then the people who disrespect you don’t get my time. Simple as that. It was in fact that simple. Dean Martin didn’t make it complicated. He didn’t need to. When you know your principles, the decisions are easy. Sammy Davis Jr. called Dean the next morning after that 1978 interview aired. You made me cry, you bastard.

Sammy said, “Sorry, I’ll make it up to you. Dinner at my place. I’ll cook. You can’t cook. I’ll have someone cook.” Same difference. They both laughed because that was the Dean Martin way. Make your stand, protect your friends, and then move on. No drama, no speeches, just action when it matters.

And then back to living life with a drink in your hand and a song in your heart. The lights went off that night in 1965. But they came back on. And when they did, something had changed. Not in the venue. That place closed down 2 years later, a casualty of changing times and bad publicity. But something changed in how people understood Dean Martin.

He wasn’t just the drunk with the smooth voice. He was the man who knew exactly when to stop singing and start acting. The man who understood that sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is simply refuse to participate. Sammy Davis Jr. never forgot it. Neither did Frank. Neither did the 350 people in that audience who had to sit in darkness and think about what had just happened.

And neither should we. Because Dean Martin taught us something important that night. You don’t have to be loud to be powerful. You don’t have to make speeches to make a point. Sometimes you just have to know your worth, know your principles, and be willing to walk away when the environment doesn’t match either.

The show’s over when you say it’s over, not when they say it is. If this story moved you, hit subscribe. Share it with someone who needs to remember that standing up for what’s right doesn’t always mean making noise. Sometimes it means making a choice. And ring that bell for more stories about the legends who understood that true cool isn’t about never caring.

It’s about caring so much that you’re willing to walk away from everything when it matters.