It was a Tuesday morning in October 2003. Paul McCartney was walking through Coven Garden in London, trying to be invisible. Baseball [music] cap pulled low, sunglasses even though the sky was gray. Jacket collar turned up. He’d learned over the decades [music] how to move through crowds without being recognized.

How to become just another face in the sea of [music] tourists and commuters and street performers that filled the cobblestone plaza. He wasn’t trying to hide because he was ashamed. He was hiding because sometimes, even after 40 [music] years of fame, he just wanted to be a person, to walk through his city, to buy a coffee, to watch the world move around him without feeling the [music] weight of being Paul McCartney pressing down on his shoulders.

The plaza was busy [music] that morning. Street performers everywhere. A juggler tossing flaming torches. A mime pretending to be trapped in a box. A classical quartet playing Vivaldi near the covered market. the usual controlled chaos [music] of Coven Garden. Paul had walked through here a thousand times. It was one [music] of his favorite places in London, anonymous in the noise.

But then he heard something that made [music] him stop walking. A voice rough, untrained, but singing with [music] such raw honesty that it cut through all the other noise like a knife. Singing let it be his song. The song he’d written in 1969 when the Beatles [music] were falling apart. The song inspired by a dream about his mother.

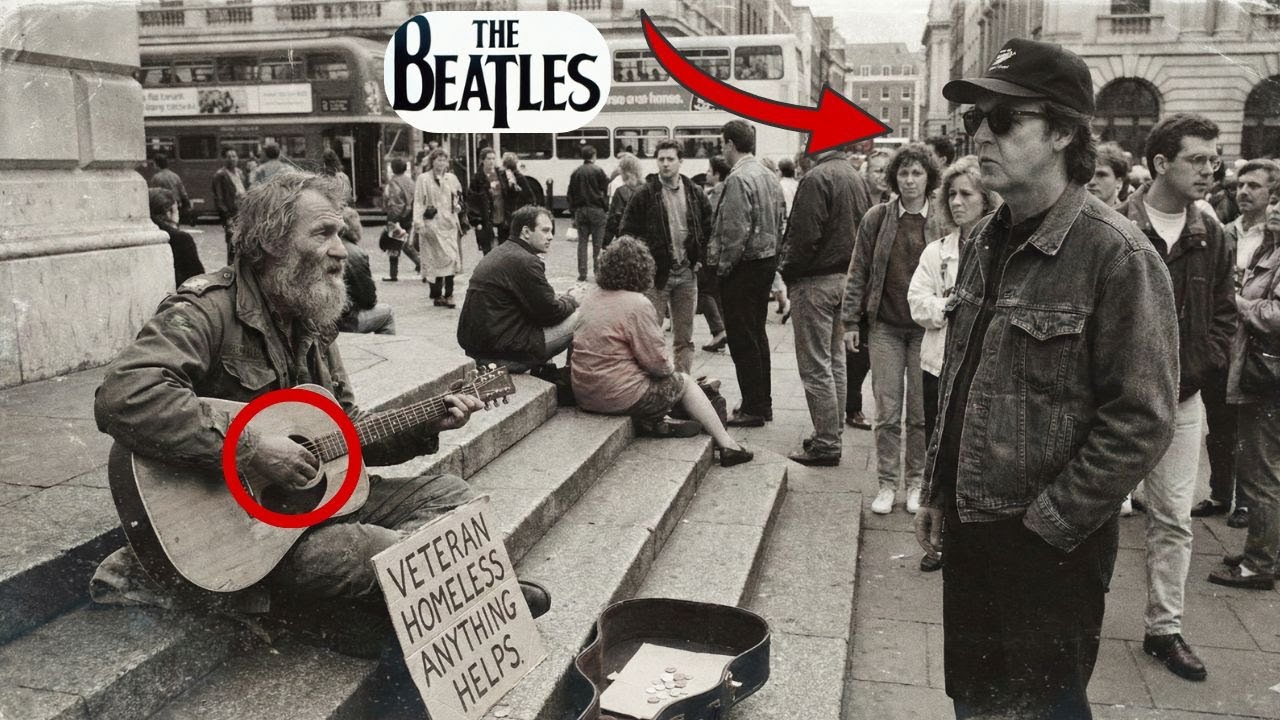

One of the most personal things he’d ever written and someone [music] was singing it badly. Off key, missing notes, but with more soul than Paul had heard in years. Paul turned toward the sound. Across the plaza, near the steps [music] leading down to the underground station, sat a man with a guitar. He was maybe 50 years old, [music] maybe 60.

hard to tell. Life had worn him down in a way that made age irrelevant. He was thin, too thin. His clothes were layers of worn [music] fabric that didn’t quite match. His hair was long and gray and matted. His face was weathered and lined and covered in a scraggly beard. He had a cardboard sign propped up next to his open guitar case.

The sign said, “Veteran, homeless. Anything helps. God bless.” Paul stood there 20 ft away watching. The man’s eyes were closed as he sang. [music] His fingers moved across the guitar strings with surprising skill, despite the fact that the guitar was missing a string and looked like it might fall apart if you breathe on it too hard.

He sang like he was alone in the world, like this was the only thing he had left that mattered. When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me speaking words of wisdom. Let it be. His voice [music] cracked on the high notes. He stumbled over the chord changes, but there was something in the way he sang those words. Times of trouble.

Mother Mary, let it be. Like he understood them, like he’d lived them. Like they weren’t just lyrics to him. [music] They were survival. [snorts] Paul felt something tighten in his chest. He’d heard Let It Be performed [music] thousands of times by professionals, by amateurs, by choirs and orchestras, [music] and drunks at karaoke bars.

But this man, this homeless veteran sitting on cold stone [music] steps with a broken guitar and desperate eyes was singing it like it was a prayer, like it was the [music] only thing keeping him alive. Paul walked closer slowly, trying not to draw attention. A few people had stopped to listen.

A couple dropped coins in [music] the guitar case. Most walked past without even glancing at him. Just another busker, just another invisible person [music] on the streets of London. The man finished the song, opened his eyes, looked down at the guitar case, maybe £15 [music] in coins and a few crumpled bills. He let out a long breath like he’d been holding it the [music] entire song.

Then he looked up and saw Paul standing there. “Just another guy in a baseball cap. Nothing special, nothing worth noticing.” “Got any requests, mate?” the man asked. His voice was horsearo, tired, British accent. working class. Play anything for a pound. Paul didn’t answer right away. He just stood there studying [music] the man’s face, trying to see past the dirt in the exhaustion and the defeat.

Trying to understand who this person was, who he’d been before life had [music] broken him down to this moment on these steps. “You play that song often?” Paul asked. The man nodded. “Every day. It’s the only one people stop for. Beatles songs always bring in more. People love the Beatles.

He said it like he was stating a fact. [clears throat] Like the sky is blue, grass is green. People love the Beatles. Why that one specifically? The man looked down at his guitar, ran his fingers over the worn wood. My mom used to sing it to me when I was a kid. When things got bad, she’d sing it and tell me everything would be all right, that we just had to let it be.

He looked back up at Paul. She’s gone now, 20 years. But when I sing it, I can still hear her voice. Paul felt his throat tighten. That’s why he’d written the song, because his own mother, Mary, had come to [music] him in a dream after she died, had told him to let it be, that everything would work out. And he’d woken up and written the song because [music] he needed to remember that feeling, that comfort, that love.

What’s your name? Paul asked. Thomas. Tommy. Tommy Walsh. You said you’re a veteran, Tommy. [music] Tommy nodded. Faulland’s 1982 Royal Navy served on HMS Sheffield was there when we got hit by the exoet [music] missile. May 4th, 1982. 20 men died that day. I lived. Sometimes I’m not sure which of us got the better deal.

His voice was flat when he said it. Matter of fact, like he’d told the [music] story so many times, it had lost all its edges, all its pain. But Paul could see the pain anyway in his eyes, [music] in the way his hands shook slightly as he held the guitar. “What happened after you [music] came home?” Tommy shrugged.

“Same thing that happens to a lot of us. Couldn’t hold down a job. Couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t stop seeing the fire and the smoke and the faces of the men who didn’t make it off that ship. Started drinking. Lost my wife. Lost my kids. Lost my flat. Lost everything. Been on the streets for [music] 8 years now. This guitar is the only thing I’ve got left.

Found it in a rubbish bin 5 [music] years ago. Fixed it up as best I could. Taught myself to play. Turns out when [music] you’ve got nothing else to do and nowhere else to be, you’ve got a lot of time to practice. Paul stood there not knowing what to say. What do you say to a man who gave years of his life serving [music] his country and ended up forgotten? What do you say to someone who’d lost everything and was now [music] sitting on cold steps playing a broken guitar for coins from strangers who barely glanced at him? Tommy looked

at Paul really looked at him for the first [music] time. There was a flicker of recognition in his eyes. He tilted his head slightly, squinted. You look familiar. Do I know you? Paul tensed, waiting. This was the moment when recognition turned into disruption. [snorts] When privacy ended and Paul McCartney, the celebrity, the legend, replaced Paul the person.

I don’t think so, Paul [music] said carefully. Tommy kept staring. Then he shook his head. Nah, must be mistaken. You just have one of those faces. He went back to looking at his guitar, adjusted the tuning on one of the pegs, even though the guitar was so out of tune, [music] it didn’t matter. Paul made a decision.

Tommy, I want you to do something for me. Can you play Let it Be one more time? Just for me. Nobody else. Just you and me. Tommy looked confused. You want a private concert? That’ll be more than a pound, mate. Paul pulled out his wallet, took out a 50 lb note, held it out. Will this cover it? Tommy’s eyes went wide.

[music] He reached for the note like he thought it might disappear. Are you serious? Dead serious. Play it for me. like you played it for your mom. Like you play it when nobody’s listening. Tommy took the money, folded it carefully, and put it in [music] his pocket. Then he positioned his fingers on the guitar, took a deep breath, and played.

This time, Paul heard everything he’d missed before. The skip in the rhythm [music] where Tommy’s fingers couldn’t quite reach the fret fast enough because his hands were stiff from cold and hunger. The crack in [music] his voice on the word trouble because Tommy knew trouble intimately. the way he closed his eyes when he sang Mother Mary because he wasn’t thinking about [music] the Virgin Mary.

He was thinking about his mom, about being a kid, about a time before fire and death and [music] losing everything. When Tommy finished, there were tears running down his face. He wiped them [music] away quickly, embarrassed. “Sorry, sometimes it hits me, you know.” “I know,” Paul said quietly. “I wrote that [music] song after my mother died.

She came to me in a dream and told me to let it be, that everything would be okay. So, I understand more than you know. Tommy looked at him, really looked, and this time the recognition [music] was complete. His mouth fell open. His eyes went wide. Oh my god, you’re him. You’re Paul McCartney. Paul smiled. Yeah, I’m him.

I just played Let It Be for Paul McCartney. I just played your song for you. Oh my god, I’m so sorry. I butchered it. I must have sounded like a complete idiot. No, Paul said firmly. You didn’t. You sang it better than I’ve heard it in years because you meant it. Every word. You weren’t performing. [music] You were surviving. And that’s what that song was always meant to be, survival. Tommy was shaking.

I don’t understand what’s happening right now. Paul knelt down next to him. Tommy, I’m going to ask you a question and I need you to be honest with me. What do [music] you need right now today? What do you need to change your life? Tommy stared at him. What do I need? Yeah, what would help? What would make a difference? Tommy looked away.

I don’t know. Everything. Nothing. I’m too far gone, Mr. McCartney. I’m not one of those stories where someone swoops [music] in and fixes everything. I’m broken. Have been for years. That’s not what I asked. I asked what you need. Tommy was quiet for a long time. [music] Then so quietly, Paul almost didn’t hear it. He said, “A place to sleep.

A real bed, not a doorway or a shelter where someone might steal my guitar while I’m asleep.” “Just one night in a real bed. That’s all I need, just to remember what it feels like to be human.” Paul nodded. “Okay, let’s start there.” He pulled [music] out his phone, made a call, spoke quietly for a few minutes while Tommy watched, confused and scared [music] and hopeful all at once.

When Paul hung up, he said, “There’s a hotel two blocks from here, the Strand Palace. I booked you a room for a month, paid in advance. [music] You go there right now. You tell them your name. They’ll give you a key. Room has a bed, a shower, a TV, everything you need.” Tommy’s hands started shaking [music] so badly he almost dropped his guitar.

A month? You booked me a hotel for a month? That’s just the start. Tomorrow morning, you’re going to get a phone call from a woman named Sarah. She works with a charity that helps veterans. She’s going to help you sort out benefits, medical care, job training, whatever you need. I’ve already talked to her. She’s expecting your call.

Why are you [music] doing this? Paul looked at him. Because you served your country. Because you survived when 20 of [music] your mates didn’t. Because you’ve been living on streets for eight years and nobody helped you. Because you sing my [music] song like you understand what it means.

Because I can help and you need help. That’s why. Tommy started [music] crying. Really crying. Not the quiet tears from before. Full body shaking sobs. I don’t deserve this. Yes, you do. Every person deserves a chance. Every person deserves dignity. You’re a human being, Tommy. You’re a veteran. [music] You’re a survivor.

You deserve so much more than what you’ve been given. Paul reached for Tommy’s guitar, the beaten, broken guitar with the missing string. Can I see this? Tommy handed it over, confused. Paul examined it, turned it over, ran his fingers along the neck. This is a good [music] guitar. Or it was. Needs work. New strings, proper tuning, but the bones are good.

It’s kept me alive, Tommy said. Paul stood up. Come with me. Where? There’s a music shop around the corner. Denmark Street. You know it? Yeah. I used to go there years ago before everything. We’re going there now. You’re getting a new guitar, a proper one, and lessons [music] if you want them, and anything else you need.

Mr. McCartney, you’ve already done too much. Paul looked at him. Tommy, I’ve made more money than I know what to do with. I’ve had every opportunity a person could have. I’ve been blessed beyond measure, and you’ve been forgotten. That’s not right. That’s not fair. So, let me do this. Not because you need charity, but because you deserve it.

Because you’re a veteran and a musician and a [music] human being who fell through the cracks. And because I can help, so please let me help. Tommy stood up. His legs were shaky. He looked like he might collapse, [music] but he stood and he nodded. Okay. Yeah. Okay. They walked together to Denmark Street. Paul kept his cap pulled low, but a few people recognized him anyway.

They stared, took pictures, but nobody [music] approached. Maybe because Paul was walking with a homeless man. Maybe because the way Paul [music] was walking with purpose and determination made it clear he wasn’t stopping [music] for anyone. At the music shop, Paul bought Tommy a Martin acoustic guitar, a good one, £1,500.

Then he bought him a case, spare strings, a tuner, a lesson book. When the shop owner realized who was buying all this, he tried to give Paul a discount. [music] Paul refused, paid full price, then tipped the staff £200. They walked back to Coven Garden. Tommy was carrying his new guitar like it was made of glass, [music] like he was afraid it might break or disappear.

Paul walked him to the hotel, waited while Tommy checked in. The hotel staff looked at Tommy’s appearance, and hesitated until they saw Paul standing there. Then they smiled and handed over the key without question. Paul walked Tommy up to the room, opened the door, let Tommy see it.

[music] The clean white sheets, the bathroom with the shower, the TV, the window overlooking the street. Tommy stood in the doorway and cried. I forgot what this felt [music] like, he whispered. I forgot what it felt like to be a person. Paul put his hand on Tommy’s shoulder. You’ve always been a person, Tommy. The world just forgot. But I’m not going to forget.

Sarah’s not going to forget. You’re not invisible anymore. Not to us. Paul left his phone number, told Tommy to call if he needed anything. Anything at all. Then he left, walked back out into the gray London afternoon, pulled his cap low again, disappeared back into the crowd. Tommy Walsh stood in that hotel room for an hour, just stood there looking at the bed, the shower, the guitar, not believing any of it was real, afraid that if he touched anything, it would all disappear and he’d wake up back on the cold steps. But it was real. The

next morning, Sarah called. Within a week, Tommy was enrolled in a program for [music] homeless veterans. Within a month, he had a small flat. Within 6 months, he had a part-time job at a music shop [music] on Denmark Street, the same shop where Paul had bought him the guitar. The owner [music] remembered him, offered him work, helping customers, teaching basic [music] guitar lessons, not much money, but enough.

Combined with his veteran benefits [music] that Sarah helped him apply for, it was enough to live. Two years later, Tommy Walsh released an album, just a small independent release. covers of Beatles [music] songs and a few originals. He called it Let It Be. The cover was a photo of him sitting on the steps at Covent Garden [music] with his old broken guitar.

The dedication read, “For Paul McCartney, who reminded [music] me what it means to be human, and for my mom, who never stopped singing. Paul bought a copy, listened to it [music] in his home studio, and cried.” Tommy never became famous, never had a hit, never played [music] stadiums, but he played small venues around London, coffee shops, pubs, street corners on nice days.

He was sober. He had a home. He had purpose. He was alive in a way he hadn’t been in years. And every time he played Let It Be, he thought about that October morning [music] when Paul McCartney stopped to listen. when the world just for one moment saw him, really saw him and reminded him that he mattered. Paul McCartney never talked about it publicly, never mentioned Tommy in interviews, never used it for publicity.

It wasn’t about that. It was about a man who needed help and [clears throat] another man who could give it. Simple as that. But Tommy told the story [music] to anyone who would listen. Not to brag, not to namerop, but to show people that kindness [music] still exists. That even when you’re invisible, even when the world has [music] forgotten you, someone might stop.

Someone might see you, someone might help. Years later, a journalist tracked down the story. Ask Paul about it. Paul just shrugged. Tommy was living on the streets. He’s a veteran. He served his country. I had the means to help. What else was I supposed to do? walk past him, pretend I didn’t see. That’s not who I want to be. That’s the thing about Paul McCartney [music] that people don’t always understand.

He wrote songs that changed the world. He played stadiums in front of millions. He’s a living legend, but at his core, he’s a guy from [music] Liverpool who understands what it’s like to struggle, what it’s like to need help, what it’s like to be human. And on that October [music] morning in 2003, when he heard a homeless veteran singing, “Let it be,” on the steps of [music] Covent Garden, Paul did what Paul does. He stopped.

He listened, and he helped. Because that’s what [music] the song has always been about. Letting things be, but also being there for people when they need you. Being the comfort, being the hope, being the voice that says, [music] “You’re not alone. You matter. Let me help.” Tommy Walsh is 71 now, still playing guitar, still living in London, still sober, still grateful, still human.

And somewhere in his flat hanging on the wall next to his Martin [music] guitar is that old broken guitar from the streets. He’ll never play it again, but he’ll never throw it away. Because that guitar was there when he had nothing, when he was invisible, when the world had forgotten him. And that guitar was there the day Paul McCartney remembered.