“They’re Taking Her!” — Japanese POW Women Beg for Mercy… The American Answer: Bring the Chaplain

They were told the officers’ tent was the last door you ever walked through.

On a scorched July afternoon in 1945, Okinawa lay in ruins—rice paddies churned to mud, stone walls chewed into teeth, the air still tasting of cordite and ash. Twenty-three captured Japanese women huddled behind wire near Naha: nurses, clerks, volunteers—thin as shadows, eyes emptied by weeks in caves and tombs. They had been raised on warnings that sounded like a litany: captured women are defiled, paraded, discarded. Do not surrender. Do not live to shame your family. Better to die.

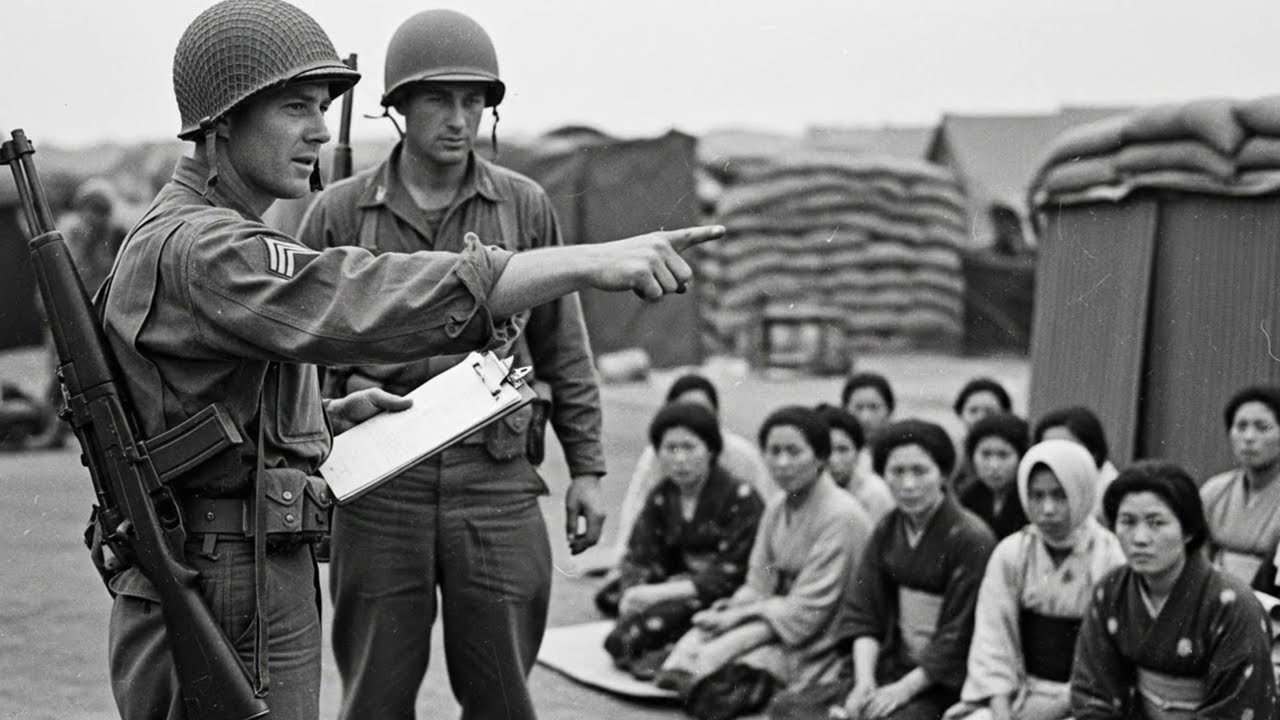

So when two American soldiers stepped up to the wire, pointed at twenty-three-year-old Nurse Yuki, and motioned her out, the women exploded into panic.

“They’re taking her to the officers’ tent!” someone screamed, voice splitting with terror. Fingers hooked the wire, knuckles white; pleas rose in Japanese like surf. “Take me instead!” an older woman cried. “She’s only a girl!” Yuki felt her legs go hollow. She stood anyway. She walked.

She expected a knife that wasn’t a knife. She expected a smile that wasn’t a smile. She expected every story the posters had promised.

What waited beneath the canvas was a chair, a teapot, and a man in uniform with a pastor’s collar.

The Walk

The camp stretched in squares—tents, trucks, men carrying crates as if the war hadn’t just cracked the world. Yuki stared at the dirt so she wouldn’t see faces. She counted steps the way you count seconds when you want time to stop. They passed a medical tent where boys too young to have ruined anyone’s life read letters with their boots off. They passed a cook tent that breathed out the heresy of onions sautéing in fat. Her mind revolted. She pictured the ocean beyond the camp, flat and bright. She pictured not being alive to see it again.

Then came the tent set slightly apart, marked with symbols she did not understand: a cross, a six-pointed star, a crescent. The younger GI ducked inside. The older one watched the horizon, bored. This indifference felt like insult and mercy together. The canvas stirred. “Come,” a hand motioned, not grabbing, not pushing—inviting.

Yuki stepped into the dim and met the most dangerous weapon the enemy possessed: gentleness.

The Chaplain

He could have been anyone’s grandfather. Gray hair, wire-rimmed spectacles, uniform worn at the edges. His collar insignia was a cross. Beside him stood a middle-aged woman with an Asian face and calm eyes. She bowed slightly.

“Please do not be afraid,” she said in flawless Japanese. “My name is Mrs. Tanaka. This is Chaplain Williams. We asked for you because you looked very frightened.”

Safe. The word didn’t fit in Yuki’s ear. She waited for a trap to spring. No trap sprang. The chaplain didn’t move closer. He nodded to the teapot. Mrs. Tanaka poured. Steam rose with a scent from another life.

Green tea.

The cup shook in Yuki’s hands. The first sip detonated memory: her mother measuring leaves with a careful wrist; a winter morning before sirens were stronger than birds. Tears slipped out before Yuki could stop them. Mrs. Tanaka placed a handkerchief near her fingers like placing a shrine offering.

“It is all right to cry,” she said.

The chaplain spoke softly. Mrs. Tanaka translated like a second heartbeat. “I am here to care for souls,” he said. “Not to interrogate. Not to harm. While you are in our custody, you will be treated with dignity under the Geneva Conventions. Food. Water. Medical care. Rest. Prayer if you wish it. Silence if you prefer that.”

Yuki’s mind scrabbled for purchase and found only new ground. “But… we were told…” She could not finish. Shame closed her throat.

“I know what you were told,” Mrs. Tanaka said. “I was born in America to Japanese parents. During the war, my family was sent to a camp. It was wrong. But we were not killed. The stories you heard were built to make you afraid. Fear keeps people fighting. Fear keeps people dying.”

The chaplain slid a Bible aside to make space, as if moving war to the margins. “You may sit,” he said. “You may say nothing. You may drink tea. For this hour, you are safe.”

The flood in Yuki broke its banks. She cried until the room blurred, until sound felt like rain on canvas. The Americans didn’t touch her. They didn’t fill the quiet with slogans. They let grief run its course like a fever.

When she could breathe again, she realized something had happened to her no enemy had accomplished with artillery or hunger: a barrier had cracked. The crack let in light.

Back at the Wire

When Yuki returned to the holding area alive, unmarked, carrying the ghost of a tea-scent, the women surged to meet her.

“What did they do? Did they—?”

“They gave me tea,” Yuki said, voice hoarse. “A chaplain spoke of laws. An interpreter… she was Japanese… she said we would be treated humanely.”

Silence clamped down. The youngest, Sato—still a girl around the eyes—whispered, “Is this a trick?” Yuki looked at their faces, at the fear that had kept them alive and trapped them at once.

“If it is,” she said, “it is the strangest trick I have ever seen.”

The First Oranges

That evening, mess trays appeared like a practical joke from a benevolent spirit: rice, fish, greens, bread softer than memory, and—impossible as a sunrise inside a tent—small oranges. Sato lifted one as if it might dissolve. “New Year’s,” she whispered. “Mother always…” She couldn’t finish. They ate. Some sobbed. Some stared at the food as if it had insulted them by existing.

After, Yuki lay on a cot and listened to the canvas breathe. She had expected to pray for death. Instead, she held a cup-shaped memory of tea.

A New Routine, Old Beliefs

Mornings brought running water. Coffee that tasted like burnt acorns and, treasonously, grew on them. Work assignments with breaks that came before collapse. In the aid station, Yuki met Tom, a medic from a place called Nebraska who carried a creased photograph of a wife and a baby named Emma like a talisman.

“Bandage,” he taught, tapping gauze. “Water.” He pointed and smiled. “Please. Thank you.” His Japanese was criminal. His gratitude was clear.

“They’re softening us up,” Michiko the schoolteacher warned at night, eyes hard even when kind. “It will change.” But days ran into one another, and the worst thing that happened was boredom.

Then Red—the auburn-haired GI who woke them with the decency to wait outside the flap—dragged in a crate of contraband from a world that hadn’t exploded: Japanese books. Poetry. A shogi set. Paper for letters. The women stared like he’d delivered snow in summer. Sato read Basho aloud. The tent filled with wind through pines, frogs in old ponds, the sound of a culture refused the dignity of extinction.

The Letters

They were told they could write home. Yuki’s hand shook.

Dear Mother, I am alive. I am being cared for.

Weeks later, a Red Cross envelope creased her palm. Her mother’s hand scrolled from a city flayed by fire: We are alive. Your father’s cough worsens. Your brother is gone—Philippines. Your sister works in a factory. We are hungry, but your letter fed us. Do not be ashamed of living. Survival is not shame.

Guilt arrived like a storm front. How could she accept seconds when her family rationed breath? That night the tent tasted of salt and grief.

“We are eating while our people starve,” Michiko said. “How do we swallow this?”

“The war starved them,” Yuki said slowly, fitting the pieces aloud. “Our leaders starved them. Here, these men feed us. I don’t know how to hold it. But both can be true.”

The Saving

Late September slumped hot. An American soldier arrived in the aid station with a leg that looked like a map to amputation. Tom threw instruments onto a tray with the speed of a man trying to beat an hour with his hands.

“Help me, please,” he said in halting Japanese. Yuki moved. Habit outran ideology. She cleaned, steadied, held a hand that tried to crush hers when pain took him under. She said soft nonsense in her language and watched his pupils come back to her voice. When the doctor finally pushed in, the worst was already better.

After, Tom said, “You saved him,” and then, carefully, “You are good nurse. Good person.”

Outside, Yuki washed American blood from her fingers and felt something rip—quietly, irrevocably. The part of her that was built by posters and speeches slid into the sea. In its place: a nurse who saves whoever is in front of her. A woman who knows that mercy is heavier than hate.

The Question Under All Questions

That night, under stars that didn’t care who drew maps beneath them, Yuki sat on a crate by the fence. Chaplain Williams and Mrs. Tanaka found her. They didn’t speak until speaking was needed.

“Why?” Yuki asked, the word raw. “Why kindness for enemies?”

“Because rules matter,” the chaplain said. “Because conscience matters more. Because every person has value, even when nations forget. Kindness complicates war. It’s supposed to.”

“If everything I was told about you was wrong,” she said, “what else was wrong?”

“That,” the chaplain said, “is a dangerous, holy question. Keep asking it.”

Surrender

In mid-August, the camp changed pitch. Voices tightened. Trucks rolled faster. The chaplain’s assistant came with a face folded into itself. Mrs. Tanaka’s voice was steady when she brought the news: “The emperor has surrendered. New bombs—atomic—flattened cities. The war is over.”

Relief and grief braided. Some prisoners sagged as if strings had been cut. Others stared like owls at daylight. Yuki tasted ash and gratitude and could not separate them.

Going Home

In November, orders came. Repatriation. Japan waited, broken but breathing. The women packed the little they had acquired: a book, a comb, a handkerchief with flowers embroidered by an American nurse who said keep it, a reminder that kindness exists. Yuki was afraid to leave safety for ruin. She was more afraid of carrying an unshareable truth home.

The last night, the chaplain asked to see her. The tent was the same and not. She wasn’t the same and was.

“You have changed,” he said, as if naming both a wound and a healing. “That’s how growth feels—strange, like wearing a new face.”

“How do I tell them?” she asked. “That the enemy gave me back my life.”

“You tell the truth,” he said. “Some will reject it. Tell it anyway.”

He pressed a small wrapped object into her palm. She unfolded cloth to find a handmade wooden cross. On the back, carved neat and small: Peace be with you.

“I don’t expect you to believe as I do,” he said. “I hope you’ll remember what it stood for here.”

Yuki closed her fingers around the smooth wood. “I will,” she said.

After

December 1945. Osaka in bandages. A mother thinner, a sister sharp with work and grief. A father already gone to the place where breath isn’t rationed. Yuki told the story in pieces, watching her mother’s eyes when she said the word chaplain, watching her sister’s mouth when she said tea.

“The Americans gave you back your life,” her mother said, touching the little cross with a tenderness that startled Yuki. “Remember that when the ruins try to make you hard.”

Years later, Yuki told her children—and then their children—what propaganda refused to print: that a scream at a wire turned into a cup of tea; that an officers’ tent became a sanctuary; that a chaplain’s collar could be a shield; that mercy broke her open in a way cruelty never could.

What the Story Proves

Fear is a fast teacher and a bad one. It keeps you alive and keeps you from living.

Kindness is subversive. It ruins simple narratives and wins battles that don’t make headlines.

The most dangerous weapon in a war is not a bomb. It’s a hand extended where a fist was expected.

“They’re taking her to the officers’ tent!” the women had screamed. They were right to be afraid—fear had been their curriculum since childhood. But when the canvas lifted, the officer was a chaplain, the weapon was a teapot, and the blow that landed was mercy.