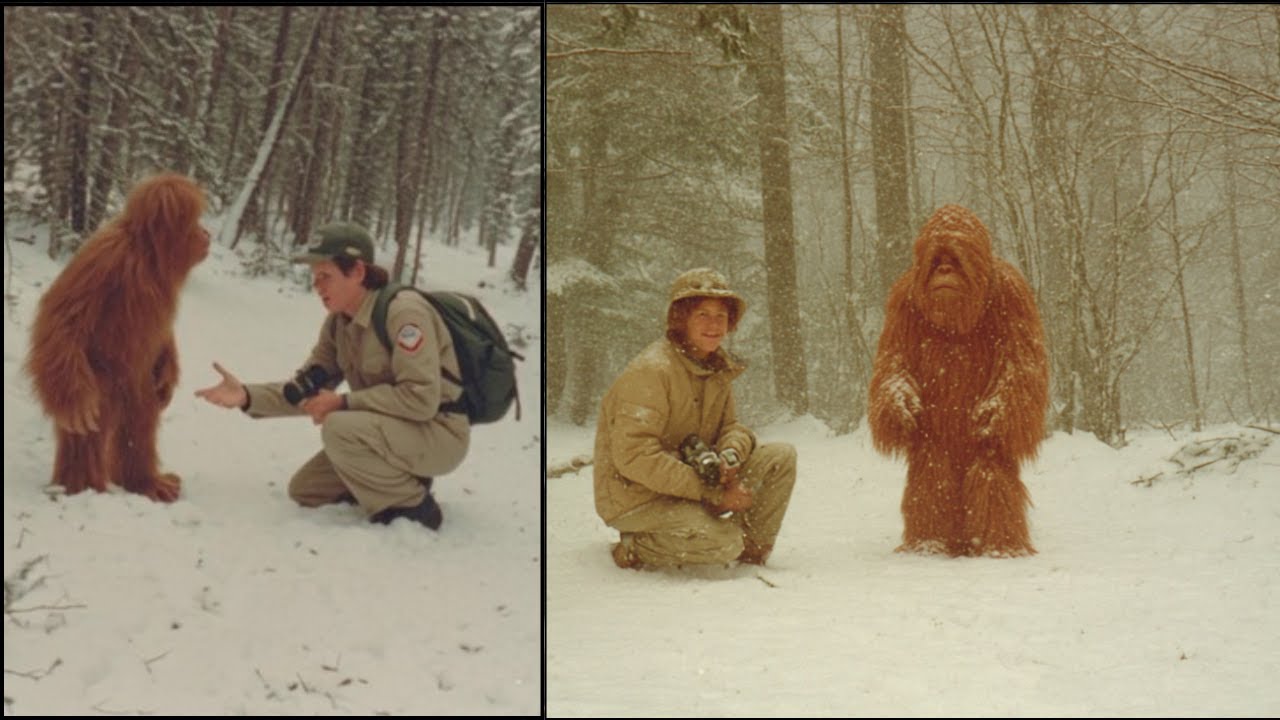

A Ranger raised 2 BIGFOOT for 30 years. He Learned Why They’re Near Extinct – Sasquatch Story

Chapter 1 — The Photo They Don’t Want You to Study

They lied to you—every last one of them. The Park Service with their friendly pamphlets. The biologists with their polished certainty. The men in Washington who speak in measured phrases like truth can be managed by tone. They look you straight in the eye and tell you that nothing larger than a black bear walks these woods. They tell you Gigantopithecus died out so long ago it’s not even worth arguing about. They call people like me delusional, attention-starved, conspiracy-brained.

.

.

.

So look at the photo. Don’t glance—look. I took it in the summer of 1998 on a throwaway Kodak, the kind with soft focus and cheap plastic guts. The clarity isn’t perfect, but anatomy doesn’t lie. Study the shoulder slope. The arms that hang too long, past the knees. The way the torso holds weight like a barrel of bone. And the two smaller figures on the log beside him—upright, attentive, holding hands like curious children. Bears don’t sit that way. Bears don’t hold hands.

Those were my boys.

Silas and Barnaby.

My name is Arthur. For forty years I wore the green uniform and the badge. I swore an oath to protect the land and its life. And then I broke that oath in the most absolute way possible: I didn’t just see a Bigfoot. I didn’t just find a print and wonder. I raised two of them. I fed them. I sheltered them. I taught them to hide from you.

For thirty years I was their father. And the reason you don’t see them anymore—the reason the woods have been getting quieter every single year—isn’t because they were myths.

It’s because of us.

We are the virus.

I’m recording this because my lungs are finished and my time is thin. Three days now there’s been a black SUV idling down on the fire road at the edge of my property line. Tinted windows. Government plates. They haven’t come up the driveway yet, but they’re watching the way predators watch a wounded animal. They know I know. They’re waiting for me to make a mistake, or to die quietly so paperwork can do what bullets don’t have to.

Before they erase me, you deserve the only honest version you’re ever going to hear. This isn’t a campfire story about monsters ripping campers apart. If you want that, go watch a movie. This is a story about family. About love. And about the single greatest mistake I ever made—the mistake of thinking a human being could bring something ancient and wild into the orbit of our modern world without poisoning it.

It began on a rainy Tuesday in October of 1994, the day my life split into before and after.

Chapter 2 — Storm Elsie and the Devil’s Finger

If you check the official logs for October 14th, 1994, you’ll see an entry next to my badge number that says: Patrol Sector 4. Cleared debris. Nothing to report. That was the biggest lie I ever wrote.

That week the Cascades took on a new personality. We called it Storm Elsie, but it wasn’t just a storm; it was an atmospheric river parked over the mountains like a punishment. Seventy-two hours of water. Creeks turned into rapids. Trails turned into soup. The slopes loosened and started to move, as if the mountain itself had grown tired of holding together.

I was sector chief then—young enough to believe dedication could outmuscle weather. While other rangers waited at the station with coffee and excuses, I ground my ’89 F-150 up the North Service Road into Sector 4, a place old-timers called the Devil’s Finger. No marked trails. No tourists. Just a jagged, shadowed wedge of backcountry that felt darker than it should, as if sunlight got tired before it reached that valley.

The rain had slowed to a freezing mist, but the air was still heavy, electrically charged. The forest was silent in a way that didn’t feel peaceful. It felt like walking into a room where an argument has just stopped—tension hanging in the air like a held breath.

Around a switchback near the 3,000-foot marker, the road vanished. A landslide had taken it—tons of shale, clay, and ancient Douglas fir sliding down in a scar of brown and gray. I parked, pulled on my yellow slicker, stepped out, and immediately sank into mud that grabbed my boots like hands.

Then I smelled it.

A landslide should smell like wet earth and crushed pine needles. Clean, sharp. This was different—thick and musky, like wet dog amplified a hundred times, with a copper edge that hit the back of the throat. Something in my body reacted before my mind could argue: the hair on my neck rose, my stomach tightened, and a primitive part of me insisted I get back in the truck and leave.

I didn’t. I grabbed my shovel, thinking I’d assess stability and call in the heavy equipment crew. I climbed over debris, slipping on wet rock, and about fifty yards upslope I saw what I first mistook for a mound of dark soaked carpet draped over boulders.

Then my brain finally caught up to my eyes.

It was a body.

Chapter 3 — The Mother in the Mud

Even crumpled, half-buried in clay, it was massive—the torso as wide as a refrigerator, the back covered in thick matted fur that swirled in patterns to shed water. I’d seen dead bears. Skinned bears. Bears have a certain architecture—short rear legs, a spine slope, paws.

This thing had long legs ending in feet. Not paws. Feet—huge, twenty inches long, thick calloused pads like tire tread, and five distinct toes. The wrongness of that detail hit me like a punch.

I dropped my shovel. The clatter echoed too loudly in the silence.

In a trance I stepped closer and touched the fur—coarse, oily, still warm. The warmth told me it had died recently, maybe within the hour. I moved to the hand: black leathery palm, deeply lined like a topographic map, with an opposed thumb built for gripping, for holding, for making. Human in the most terrifying way.

I whispered, “My God,” and the steam of my breath hung in the damp air.

I needed to see the face. I needed to look it in the eye even if it was dead, because some part of me believed that if I confirmed the face was monstrous, I could return to the world I understood. I leveraged the shoulder with all my strength. The body rolled slightly.

The face that emerged wasn’t a snarling beast. It was heartbreakingly human: dark charcoal skin, broad flat nose, heavy brow ridge shading closed eyes, thin lips, cheekbones that carried a kind of dignity. Female. Matriarch. An elder.

And the position of her body—curled inward, arms locked tight across her chest—made the truth plain in a way that hurt: she hadn’t died trying to escape the slide. She had died shielding something. She’d taken the mountain on her back to protect what she held.

That’s when the sound came—faint, muffled by fur.

“Woo… woo… woo…”

I froze. A survivor.

I dropped to my knees in the mud and dug frantically at the packed clay against her chest. Her arm wouldn’t budge at first; the muscle density was absurd. I planted my boot against her hip and heaved until my shoulders screamed. Slowly her arm lifted a few inches.

Two pairs of amber eyes stared out from the darkness of her embrace.

Small—small only in the way a two-year-old human is small—covered in downy fur the color of dried pine needles. Twins. Shivering so hard their teeth made a faint clicking sound. One turned his head and looked at his mother’s face, then at me, and made a sound that shattered something professional inside my chest.

It wasn’t animal noise.

It was a question.

A child asking: Fix her.

Tears came before I realized I was crying. Protocol screamed in my head—secure the scene, call dispatch, wait for biologists, follow the chain. But I’d been a ranger long enough to know what the chain did to wolves that crossed invisible lines. I’d heard whispers about labs that don’t exist on maps. If I called this in, these orphans wouldn’t become a miracle.

They’d become inventory.

Then my radio crackled on my belt. “Unit 4 Alpha, dispatch. Reports of seismic activity in your sector. Copy?”

The decision was suddenly not theoretical. It was now. Ten seconds to decide which kind of man I was.

Chapter 4 — The Lie That Became a Life

I stared at the radio as if it were a live grenade. Then I stared at the twins clinging to their dead mother. My career, my oath, my pension sat on one side of the scale. Two helpless souls sat on the other.

Dispatch crackled again, sharper. “Unit 4 Alpha, report status. Two federal biological survey teams inbound to your coordinates. ETA ten minutes.”

Biological survey teams. In my entire career, I’d never heard of “bio teams” deploying that fast during a storm. They weren’t coming for the landslide. They were coming for the heat signature under the mud. They had sensors. Satellites. Ground arrays. Something.

They were coming for them.

I keyed the mic, forced my voice into bored competence, and lied like a man saving his own child. “Dispatch, negative on coordinates. I’m washed out at South Ridge. Road’s gone. Turning around. Nothing out here but mud and rocks. Over.”

A pause. Long enough to taste fear.

Then: “Copy. Return to base.”

I clipped the radio back on and worked like a madman. I couldn’t dig a grave in rocky slurry, so I pulled more shale down, rolled boulders over the mother, arranged deadfall and snapped branches, sculpting the debris into a believable landslide mound. I covered her face with moss and whispered an apology that tasted like ash. “I promise I’ll keep them safe.”

The twins hissed when I reached for them, a low guttural warning born of terror. I took off my yellow slicker, threw it over them like a blanket-net, scooped them up. They were heavy already, dense muscle and bone—forty pounds each, at least—and they struggled until the warmth calmed them into exhausted shivers.

I ran to my truck, threw the bundle onto the passenger seat, slammed the door, and reversed down the mountain without headlights, navigating by lightning flashes and memory. In the valley I saw distant headlights cutting through rain—men coming the way predators come, silent and sure.

I didn’t go to the ranger station.

I drove to my private fire lookout cabin five miles deep in restricted zone, a place off the official maps, a place I’d used to disappear from my own life.

That night I became a felon.

And I became a father.

Chapter 5 — Silas, Barnaby, and the War of Hiding

You think raising human kids is hard? Try raising two wild primates that grow like bamboo and carry strength like a weapon by the time they can run. The first week was hell. They wouldn’t eat. They huddled behind my woodstove holding each other and making small broken whimpers that didn’t sound like animals. They sounded like grief.

For three days they starved themselves as if hunger was an offering to the dead. I tried cow’s milk, dog food, raw steak. Nothing. On the fourth night, desperate, I mashed cattail roots with wild berries and honey and set the bowl on the floor, backing away like I was offering to a dangerous god.

The smaller one crept forward, dipped a finger, licked it. His eyes widened. He grunted at his brother, and suddenly both were eating, smacking softly, alive again.

That was the night I named them. The bigger one, always positioning himself between me and the other, serious and watchful, I called Silas. The smaller one—curious, bright-eyed, destined to get into everything—I called Barnaby.

Feeding them was the easy part. Hiding them was the war.

By a year old they were four feet tall. By two they were too fast. By three they were clever enough to test boundaries. My cabin smelled like a zoo no soap could scrub away. I stopped inviting people over. My wife, Sarah, started to ask questions I couldn’t answer. She could smell them on me—musk and earth that clung like smoke.

In 1996, a hiker wandered off-trail and almost caught them playing near the treeline. I charged the man waving an axe like a lunatic and screamed about restricted zones and federal fines until he ran, pale-faced, muttering about a standing bear. That night I realized the boys needed more than hiding spots.

They needed fear.

I sat them by the fire. They sat cross-legged, mimicking me like children. I looked into amber eyes and told them the truth in the simplest language I had. “Men are bad. Men will kill you. If you see a human, you run. You hide. Never let them see you.”

Barnaby pointed at my chest, confused.

“Even me,” I whispered, throat burning. “I am danger.”

They didn’t understand then.

They would.

Chapter 6 — The Price of Being a Keeper

Secrets don’t kill you all at once. They eat you cell by cell until the person you were is gone. By 1999 the boys were five years old—kindergarten in human terms, a linebacker in their world. Nearly seven feet tall, dense muscle, forty pounds of protein a day. I bought half cows from farmers, lied about sled dogs, stole roadkill at three in the morning like a criminal on a mission.

I was exhausted, paranoid, and absent.

Sarah noticed because love is a kind of tracking. She asked if there was another woman. I almost laughed at the innocence of that guess. On Christmas Eve I chose the boys over her because a blizzard made the mountain howl like screaming and I feared they’d panic and run into the storm. When I came home the next morning, her suitcases were by the door. No yelling. No plates. Just disappointment like a knife.

“Whatever is up there,” she said softly, “you love it more than you love me.”

I wanted to drag her up the fire road and show her the miracle, to let her touch a warm furry hand and understand. But Sarah had a big heart and a loose tongue. If she told anyone, the boys would be dead by the next sunrise. So I let the love of my life walk away while Sasquatch hair clung to my coat like guilt.

That day Arthur the husband died.

Arthur the keeper lived.

In the loneliness that followed, Silas would sit beside me on the porch at night, imitating my posture, and let out a low rumbling purr that vibrated through the boards. Comfort without words. Family in a shape the world refused to accept.

And yet the danger never stopped growing. Technology crept closer. Trail cams. GPS. Drones. The world shrinking, mapping, watching. I knew luck isn’t forever.

Then in 2005, Silas saved my life.

A grizzly sow charged me in a berry patch—cubs nearby, pure death. I fumbled for my pistol and was too slow. She hit me like a vehicle and I cracked a rib against a pine. Claws rose. Darkness waited.

Then the forest shook with a roar that vibrated my teeth.

Silas exploded out of the treeline and collided with the bear like a freight train. He caught her paw midair like you catch a child’s hand, roared in her face, and shoved her backward until she rolled down the embankment. The bear did the math and fled.

Barnaby appeared with sphagnum moss, chewed it soft, and pressed it to my bleeding arm with a gentleness that made my eyes burn. They carried me back to the cabin like I was fragile. They took turns patting my leg and checking my warmth through the night.

That was the shift.

I wasn’t their keeper anymore.

I was the pet they loved.

And that terrified me, because I knew if men ever came for them, Silas and Barnaby wouldn’t run. They’d stay and fight for me. And against bullets—no matter how strong they are—nothing wins.

Chapter 7 — The Cough That Ended a Species

I always thought it would end with gunfire. Me on the porch with a Winchester, holding off the world while my boys vanished into timber. I was wrong. The end didn’t come with a bang.

It came with a cough.

About six months ago, Barnaby changed first—sleeping too much, eyes dull, then a hacking cough like rocks in a tin can. Silas followed. Wet, deep coughs that shook their chests. Fur fell out in clumps. Skin underneath turned gray and irritated. They lost weight so fast it looked like the mountain was stealing them.

I panicked and bought antibiotics meant for horses, ground pills into venison stew, prayed into the stove heat. Nothing helped. I took a blood sample from Barnaby—he didn’t even flinch—and mailed it to a private lab under a fake name. The vet called me personally, voice spooked. “I don’t know what animal this is,” he said, “but its immune system is collapsing. Severe reaction to human pathogens. Common viruses we carry every day—poison to it.”

The phone slipped from my hand.

It wasn’t government toxins.

It wasn’t pollution.

It was me.

My breath. My clothes. My decades of closeness. I’d been slowly poisoning them with love.

Then the neighbor’s dog barked and went silent. And above the trees came the low mechanical rhythm of a surveillance drone running grid patterns. Silas and Barnaby were burning with fever—one hundred and six degrees in mountain cold—lighting up thermal cameras like flares. A red strobe blinked above my cabin, circling.

The emergency radio crackled to life, cold and official. “Occupant at grid Four Zulu. You are harboring a biological hazard. Remain indoors. Containment teams inbound. ETA two minutes.”

Two minutes.

Silas tried to stand, sensed danger, then collapsed into coughing that brought him to his knees. He looked at me—not fear for himself. Fear for me. He knew sky-eyes meant bad men.

I didn’t shoot them. I couldn’t. But I couldn’t let them be taken alive into cages, nor dead onto a slab. Under my pantry rug was a hatch I’d never told anyone about—not even Sarah—leading to an old bootlegger’s tunnel from the 1920s. It ran through bedrock into an abandoned silver mine deep inside the mountain.

We crawled. Three hundred yards through mud and darkness while boots hit my porch above and my front door shattered. The mine chamber was cold and invisible to thermal. But it wasn’t invisible to fever.

Barnaby went first. His eyes cleared for one brief second, he squeezed my hand, and then the light left him. Silas lasted an hour longer, head heavy in my lap, purring one last time before his lungs quit.

I sat with them for two days.

Then I did the only thing left that could keep the world from taking them: I collapsed the mine. I pulled a rope tied to a rotting support beam and the mountain came down, sealing them behind tons of rock. Not a grave.

A vault.

A pyramid for the kings of the forest.

When I crawled out through a ventilation shaft miles away and returned to my cabin, the men were gone. They’d ransacked the place, found beds, hair, signs. They knew something had lived here. But without bodies, they had nothing to display, nothing to prove.

So they watched me instead, waiting for grief to make me careless.

Now they’re walking up my driveway.

If you’re hearing this, it means I’m gone or silenced. So listen: if you ever see a shadow in the woods that moves wrong, or a footprint too human, do not follow it. Do not take a picture. Do not try to save it. Turn around and walk away.

Because once we touch the mystery, we don’t protect it.

We destroy it.