He was only 18, a poor southern boy with calloused hands, secondhand clothes, and a voice that didn’t fit anywhere. He grew up believing in God, hard [music] work, and dreams too big for his small town. People said he was different, too shy to lead, too strange to blend in, and far too bold to know his place.

But inside that quiet young man was a fire. A faith that whispered, “Maybe different is exactly what the world needs.” While others followed the rules, he followed the rhythm. The gospel from Sunday mornings, the blues drifting from Bee Street, the country ballads his mama loved, it all lived inside him, waiting to be heard.

One hot summer day in 1953, he climbed out of his work truck, [music] walked into a small studio on Union Avenue with $4 in his pocket, and said he wanted to make a record for his mother. He had no idea that by pressing record, he was about to change everything. But he wasn’t just another dreamer. He was a man destined to be a king.

A name the world would never forget. Elvis Presley, a legacy that would echo far beyond music. A story of faith, fire, and the price of greatness. This is the story of the diamond nobody saw. A young dreamer who went against the tide, defied every rule, and turned faith, pain, and difference into the sound that would shake the world.

Stay until the end. Because before the king ruled the stage, he first had to believe when no one else did. The boy from Tupelo. Before the fame, before the gold records, before the world called him the king, there was just a poor boy from Tupelo, Mississippi, a boy who believed music [music] could save him.

He was born on January 8th, 1935 in a tiny two- room house built by his father. His twin brother, Jesse Garin, was still born. Elvis survived, and that shadow of loss followed him all his life. Neighbors said Glattis Presley never let her boy out of her sight. She wrapped him in love so fierce it almost hurt.

They didn’t have much. No car, no radio at first, but what they had was music. Church on Sundays, gospel choirs that made the walls tremble. And out on the streets, the sound of the blues drifted through open windows. That was the world Elvis grew up in. A mix of black and white, sacred and sinful, heaven and heartbreak.

When he was 10, his mother took him to the hardware store in Tupelo. Elvis wanted a rifle. Glattis shook her head and said, “Let’s get something that won’t hurt nobody.” So, she bought him a guitar instead. It cost $7.75. And changed history. At first, he was shy about playing it in front of anyone. He’d sit on the porch after supper, picking out hymns and love songs while the cicas sang along.

His father, Vernon, would listen quietly. His mother would smile, humming the words. That little house, barely 400 square ft, became his first stage. As he grew, the family moved to Memphis, chasing work like so many others during those hard years. They lived in government housing, poor, proud, and hopeful. At school, Elvis was quiet, polite, a little different.

He sllicked back his hair with Vaseline and carried his guitar everywhere. Some kids laughed at him, others just didn’t get him. But music was his refuge, a mix of black [music] rhythm and white country twang that no one could quite name. When teachers asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, he’d smile and say, “I just want to sing.

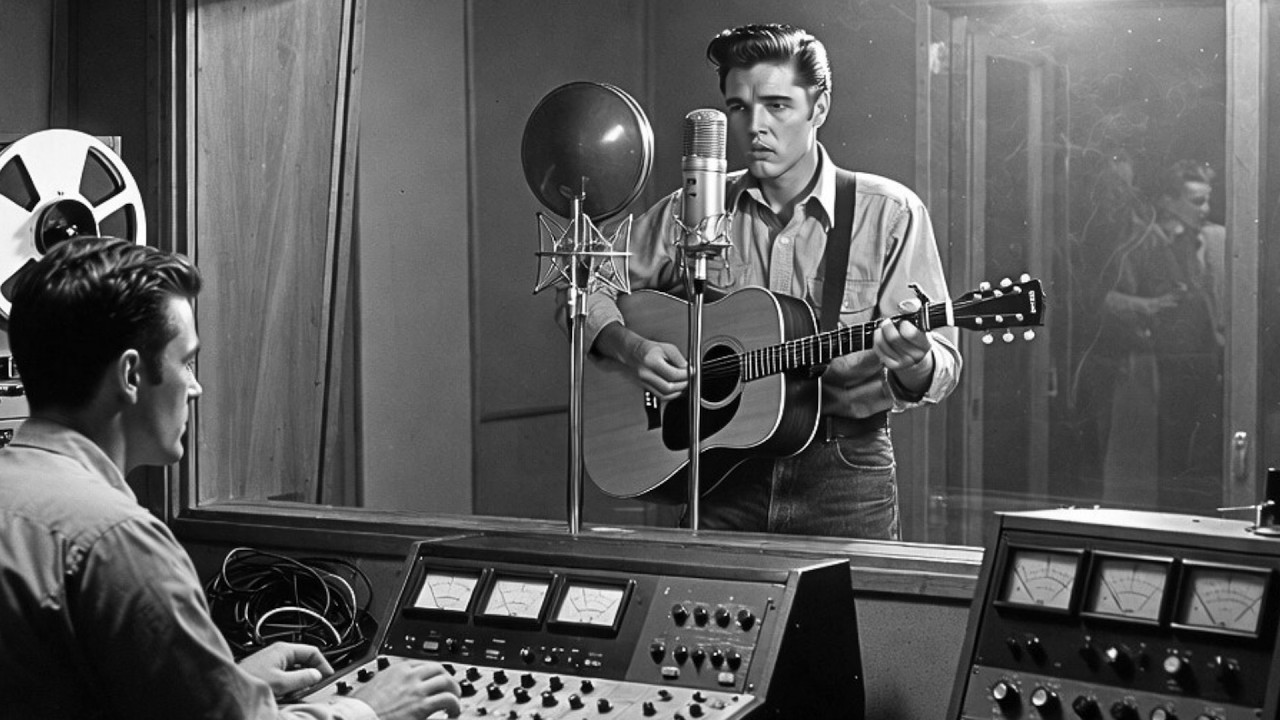

” And one day, that dream, that same dream born in a two- room shack in Tupelo, would lead him to a small studio on Union Avenue [music] with nothing in his pockets but $4 and a hope too big for the world to ignore. The $4 recording. It was July 18th, 1953. [music] Memphis was melting under the summer heat. And on Union Avenue, a shy 19-year-old parked a beaten up truck [music] in front of Sun Records.

He sat there for almost half an hour, staring at the front door, the door [music] that separated ordinary life from the dream he’d carried since childhood. Inside behind that glass, Marian Kisker, Sam Phillips’s assistant, was typing invoices. She’d seen dozens of young men walk in with guitars. Each one certain he’d be the next big thing.

Most were gone within minutes. When the door finally opened, she looked up and saw a tall, nervous boy in worn [music] out clothes. He clutched his guitar like it was both a shield and a prayer. “Can I help you?” she asked. “Yes, ma’am.” >> [music] >> he said softly. I’d like to make a record for my mama. It cost $4.

All the money he had left that week after paying rent and gas. Marion led him into the small recording booth, walls covered in burlap, a single microphone hanging from the ceiling. No air conditioning, just the steady hum of tape machines, and the scent of warm metal. “What do you sing?” she asked.

“A little of everything,” he said. >> [music] >> Who do you sound like? I don’t sound like nobody. She smiled politely. She’d heard that line before, but when he started to sing my happiness, something in the room shifted. His voice was nervous, a little shaky, but there was a sincerity that cut through the static, a blend of country innocence and gospel ache, a sound that didn’t fit any category.

Marian leaned forward, listening carefully. When he finished, she whispered to herself, “He doesn’t sound like anybody.” She wrote it on the note card attached to his tape. “Good ballad singer, hold.” Elvis stepped out of the booth, wiping sweat from his forehead. He thanked her, smiled awkwardly, and left the same way he came, quietly, almost invisible.

Outside, the Memphis son hit his face like fire. He sat behind the wheel of his truck and looked down at his hands, still trembling from the adrenaline. He didn’t know if he’d done well or made a fool of himself. He only knew one thing. For the first time in his life, [music] he’d walked through that door and left his voice on tape.

And somewhere inside that studio, Marian Kisker placed the reel with his name, Elvis Presley, [music] on a small metal shelf next to dozens of forgotten dreams. She didn’t know it yet, but that tape would soon rewrite the history of American music. The forgotten year. After that first recording, nothing happened. No phone call, no letter, no second chance.

For almost a year, Elvis Presley went back to being just another young man in Memphis. He drove trucks for Crown Electric, hauling cables and equipment across the hot southern roads. His hands, once trembling in front of a microphone, were now covered in grease and dust. But even behind the wheel, he never stopped humming.

He’d sing gospel in the cab, blues in the parking lot, and old country ballads when the radio faded into static. Every night, he’d go home to the small apartment he shared with his parents. Glattis would still call him my boy, and he’d sit at the kitchen table telling her stories about deliveries and long drives. But deep down, she knew his heart was still in that studio.

Sometimes he’d take out his guitar and play softly for her. She’d stop whatever she was doing, close her eyes, and listen. To her, his voice was proof that their struggles meant something. To him, it was a reminder that maybe, just maybe, she was right. A few times that year, Elvis stopped by Sun Records just to talk. He’d ask Mary and Kisker if there was any work, any session, any chance.

[music] She’d smile kindly, but shake her head. Nothing yet, honey. But I’ll remember you. He always thanked her, tipped his head, and left quietly. No drama, no complaints, just waiting. Meanwhile, Sam Phillips was [music] chasing a dream of his own, to find a white man who could sing like a black man.

Someone who could bridge the racial divide of American music. He didn’t know that the voice he was looking for had already walked through his door a year earlier. The days turned into months. Elvis’s truck routes stretched longer, his faith stretched thinner. But whenever discouragement crept in, he’d remember that brief moment in the booth.

The way his voice filled that small room, the way Marion had looked at him, curious and surprised. Maybe it meant something, maybe it didn’t. But he kept believing that someday someone would listen. And then one evening in June of 1954, while Elvis was finishing a shift at Crown Electric, the phone rang at home. Glattis picked it up.

A woman’s voice said, “This is Marian Kisker from Sun Records. Tell Elvis Sam wants him to come by the studio tonight. He might have something for him.” Glattis smiled so wide she nearly cried. When Elvis came home, she told him, and for the first time in months, he looked like a man with fire in his eyes. He didn’t know it yet, but that phone call would pull him out of obscurity and into immortality.

That’s all right, mama. It was July 5th, 1954. The night Memphis turned electric inside Sun Studio. The air was thick. No air conditioner, just ceiling fans stirring hot dust. Sam Phillips, the producer, was restless. He’d called in a few local musicians to cut a demo. Scotty Moore on guitar, Bill Black on bass, and the shy young man Marian had mentioned, Elvis Presley.

Sam was still skeptical. He’d seen hundreds of singers. But something about this boy’s tone stuck in his mind. That mix of gospel warmth and hillbilly twang. They started with a slow ballad. It didn’t work. Elvis’s voice was tight. His nerves obvious. Song after song fell flat. Hours passed. Sam leaned back in his chair, sighing.

Scotty wiped sweat from his [music] forehead. Bill looked at the clock. It was nearly midnight. Let’s call it [music] a night,” Scotty muttered. But then something unexpected happened. As they packed up, Elvis grabbed his guitar and started fooling around. Half joking, half relieving the tension.

He began strumming That’s All right, Mama, a blues tune by Arthur Crutup. He wasn’t trying to impress anyone. He was just having fun. But the way he sang, fast, loose, joyful, sounded like nothing Sam had ever heard. Sam’s head snapped up. He rushed out of the control room and shouted, “What are you doing?” Scotty shrugged, laughing, “We don’t know.” Sam’s eyes were wide.

“Well, back up and do it again.” Elvis laughed nervously, [music] tapped his foot, and began again, faster this time. Voice playful, rhythm alive. Scotty joined on lead guitar. Bill slapped the bass like a drum and the room exploded into pure energy. Three men, one take and lightning [music] in a bottle.

Sam stood frozen, grinning like a man who’ just witnessed fire being invented. He turned to Marion and whispered, “That’s it. That’s the sound I’ve been looking for.” When the song ended, the silence was deafening. No one moved. Then Elvis, shy again, asked, “Was that okay?” Sam laughed. Okay, son.

I don’t even know what that was, but it’s new. A few nights later, Sam handed the record to Dwey Phillips, the popular DJ at WHBQ radio. No relation. [music] Dwey put it on air without hesitation. At 9:30 that night, Memphis heard, “That’s all right.” for the first time. The switchboard exploded with calls. Listeners begged, “Play it again.

Who is that?” Some thought Elvis was black. Others swore he was white. No one could agree. And that confusion was exactly the magic. Dwey played it 14 times in a single night. Then he called Sam and said, “Get that boy down here. The phones won’t stop ringing.” When Elvis arrived at the station, he was shaking. He thought he was in trouble.

While Dwey talked on air, Elvis sat hidden in the studio bathroom, too nervous to face the world. Finally, Dwey waved him in. The red light blinked. Live radio. So, Elvis, what school did you go to? That one question told listeners what words couldn’t. Elvis was white. And just like that, the lines dividing black and white music began to blur forever.

By the end of the week, That’s All Right was everywhere on jukeboxes, radios, barber shops, porches. Memphis had never heard anything like it. [music] The world hadn’t either. That night, a new sound was born. A sound no one could define because it didn’t belong to any box, any color, any rule. It was raw, reckless, and alive.

And at its center was a 19-year-old boy who just wanted to sing for his mama. They called it rockabilly. History called it the birth of rock and roll. The birth of the king. When That’s All Right hit the radio, everything [music] changed. Within days, Sun Records was flooded with calls. Dewey Phillips couldn’t keep up with the demand.

Everywhere he went, people asked the same question. Who is that boy? Elvis was suddenly in motion. Interviews, more sessions, and his first performances with Scotty and Bill. At the Overton Park Shell in Memphis, he stepped onto a real stage for the first time. He was nervous, his legs shaking uncontrollably. [music] The crowd started laughing until they realized the shaking was part of the rhythm. Then they screamed.

That night, something inside him clicked. The shy boy disappeared. The performer was born. By the end of 1954, That’s All Right and Blue Moon of Kentucky were spinning across the South. Newspapers began writing about this young man who sings like nobody. Sam Phillips smiled. His dream had found its voice. At home, Glattis listened to her son’s record on a small radio by the window.

Tears rolled down her cheeks. She looked at Vernon and whispered, “That’s our boy.” For Elvis, that moment meant more than any fame that would follow. Because it wasn’t about glory. It was about proving that dreams born in poverty could reach the world. In the years that followed, he would become the most famous entertainer on earth.

But every success, every concert, every scream traced back to that single reel of tape recorded for $4. That was where the king was born. Not in a palace, but in a tiny studio with peeling paint and tired equipment. Not with riches or titles, but with heart, hunger, and faith. He didn’t fit in any box, so he built his own.

And from that small room on Union Avenue, his voice crossed every line. race, class, time itself, and kept on echoing long after he was gone. The king wasn’t crowned. He was recorded.