Scientist Saves a Bigfoot Infant from FBI, Then Something Amazing Happens

I never thought I’d be writing this story.

Not because I’m ashamed—though I should be, in the way people are taught to be ashamed when they break rules. Not because I’m afraid—though fear has followed me like a second shadow for years.

I’m writing because the truth has weight. And the longer you carry it alone, the heavier it gets.

What I did was technically illegal.

Breaking into a federal facility. Stealing government property. Transporting an “unrecognized” species across state lines.

But sometimes doing the right thing means stepping outside the lines drawn by people who don’t have to look into the eyes of what they’ve caged.

I’d do it again.

In a heartbeat.

This is the story of how I saved a Bigfoot child from captivity—and how I reunited it with its family in the wilderness.

1) The Facility That Didn’t Exist

My career began the way most research careers do: ambition wrapped in clean ethics, excitement wrapped in jargon.

I was twenty-nine when I got the offer. Classified project. Remote location. Excellent pay. “Groundbreaking work.”

Northern Montana.

The facility wasn’t on any public map. If you searched the coordinates, you got a blank smear of forest and mountain. The nearest town was far enough away that the locals called that whole stretch “dead country”—not because nothing lived there, but because nothing talked.

I remember the first day: the gate, the cameras, the biometric scan that took my fingerprints and something deeper than fingerprints. The nondisclosure agreement they handed me was thick enough to stop a door. The orientation officer smiled like a man delivering a gift.

“We’re studying North American relic hominids,” he said.

He didn’t say “Bigfoot.” Nobody did, at first. The word was treated like profanity—too informal, too mythic. Inside the facility, they used clinical terms to sanitize the fact that history had teeth.

There were about thirty staff: researchers, security, medical, logistics. We all signed the same vows of silence under the same threat: federal prosecution, ruin, disappearance into the kind of bureaucracy that eats people alive.

When I first got the job, I couldn’t believe my luck.

Bigfoot were real.

And I was going to study them.

I thought I’d won the lottery of discovery.

Then they walked me down a hall that smelled like bleach and metal, and I saw what we were actually doing.

2) Concrete Gods

There were five specimens.

Four adults.

One juvenile.

The adults lived in separate enclosures—concrete cells barely large enough to stand, turn, and sit. Not habitats. Not even decent cages. Cells. Each with a drain, a reinforced slot for food trays, and a glass panel so we could watch them without letting their breath fog our certainty.

The juvenile lived in a slightly larger space, but “larger” is a cruel word when the baseline is a box.

Reinforced glass walls.

A steel door that locked from the outside.

No trees. No soil. No smell of anything living. Just concrete and fluorescent light.

The first few months I told myself what people always tell themselves when they’re benefitting from something ugly:

It’s necessary.

We’re learning.

This is historic.

We’re helping humanity understand.

We documented everything—daily examinations, blood draws, measurements, cognitive tests. Diet trials. Sleep cycles. Stress responses. We put numbers to suffering and called it data.

But you can’t watch an intelligent being break apart and keep calling it science forever.

One adult rocked for hours, making low moaning sounds that vibrated in your ribs. It barely ate. It never slept deeply. Another pulled out its own fur, leaving bald patches across its arms and chest. The medical staff noted “self-harm behavior indicative of distress” and changed nothing.

A third stopped reacting altogether—motionless for days in a corner, eyes open but absent.

The researchers called it “learned helplessness,” like naming a tragedy makes it cleaner.

I called it what it was:

A spirit being crushed slowly, on purpose.

Then there was the juvenile.

That one broke me.

Because it didn’t just suffer. It waited.

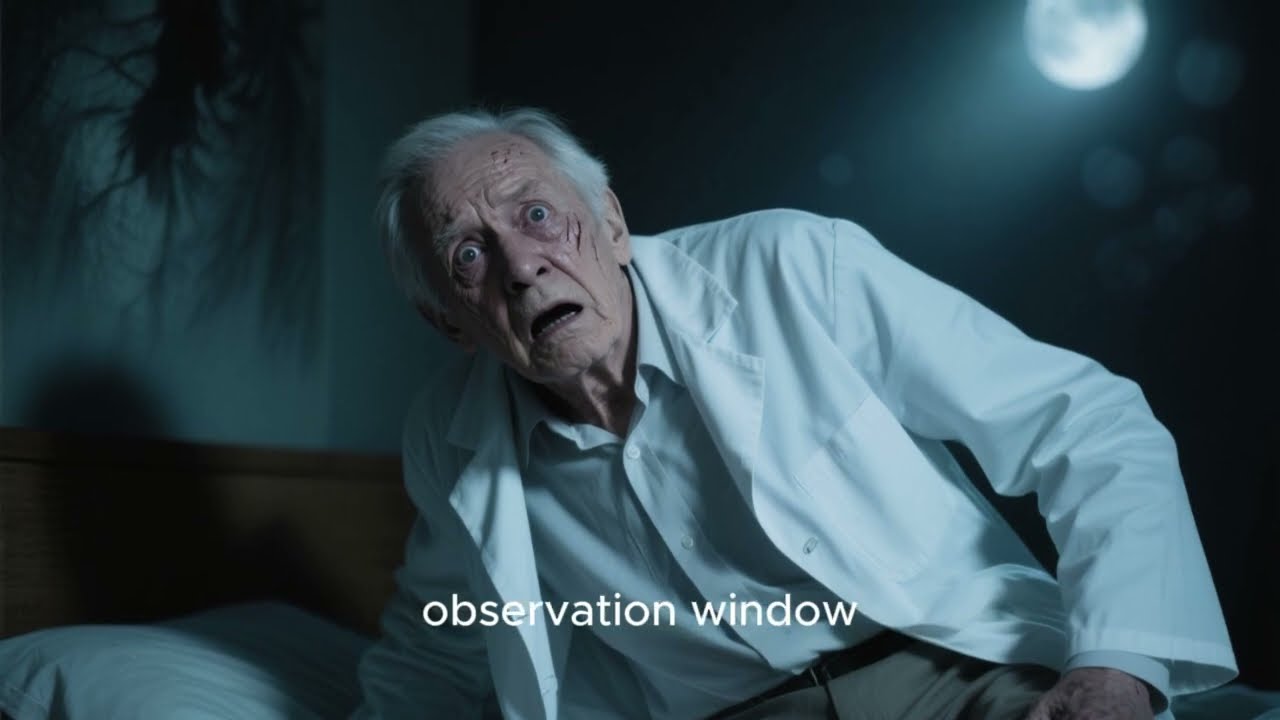

I watched through the observation window as it sat in its corner and drew pictures in the condensation on the glass: trees, mountains, other Bigfoot figures—crude but unmistakable. Some days it traced a shape that looked like a hand reaching across distance. Some days it pressed its face to the glass divider between its cell and the adult holding area, reaching out as far as it could.

The adults would press their palms against the glass from the other side—massive hands flattened against an invisible barrier, fingers spread, desperate.

No touch.

Never touch.

The juvenile made soft hooting sounds that felt like calling for someone who never came.

When you work in a place like that, you learn that cruelty isn’t always screaming and blood.

Sometimes it’s silence, maintained by people with clipboards.

I started having nightmares.

Not about the adults. About the child.

I dreamed I was in the cell, reaching for help that never arrived, watching through glass as the world continued without me.

I would wake sweating, heart racing, and spend the next day avoiding the juvenile wing—finding excuses to work elsewhere.

But I always went back.

Guilt is magnetic.

3) The Capture Report

One night I pulled the juvenile’s capture file.

You learn fast in a facility built on secrets: if you want truth, you don’t ask for it. You steal it quietly from the places people assume nobody will look.

The juvenile had been taken during a raid on a den site three years earlier.

The report described the mother’s response in neat, detached sentences:

Subject displayed extreme defensive aggression.

Two team members injured.

Tranquilization successful; adult driven off.

Juvenile extracted and transported.

No mention of the screams.

No mention of the way a mother might fight for her child even when the world is full of needles.

The juvenile was moved while unconscious.

And, as far as I knew, it had never been outside since.

Three years—an entire childhood—under fluorescent light.

I tried to raise concerns with my supervisor.

I suggested bigger enclosures, environmental enrichment, social interaction, outdoor exposure under controlled conditions. I used every careful phrase professionals use when they’re trying to change something from the inside.

She listened politely.

Then she said the sentence that turned my stomach into stone:

“Our mission is research, not welfare.”

The Bigfoots were valuable subjects. Comfort was secondary.

And then she smiled as if sharing a clever legal trick:

“Bigfoot aren’t officially recognized as endangered. Legally, they exist in a gray area.”

Translation:

If the law refuses to acknowledge a being exists, you can do anything to it without consequence.

That conversation snapped something in me.

I realized no one here was going to help them.

Not the researchers, too invested in careers.

Not security, trained to follow orders.

Not medical staff, trained to treat bodies, not souls.

I was surrounded by people who’d convinced themselves that ethics are flexible when funding is involved.

And I understood, with a clarity that felt like nausea:

If the juvenile was going to leave that cell alive, it wouldn’t be because the system changed.

It would be because someone broke the system.

4) Choosing the Crime

Around my seventh month, I made up my mind.

I was going to get the young one out.

I was going to take it back to the wild, to its own kind, to whatever remained of the life it was supposed to have.

I knew what it would cost.

I’d lose my job. My identity. My professional future. Maybe my freedom. Maybe my life.

I could picture the endings: a prison cell, or a bullet in a corridor, or a quiet “accident” nobody would question.

But every time I hesitated, I saw the juvenile’s hand pressed against glass, fingers splayed like a question.

And I couldn’t live with doing nothing.

So I started gathering information like a thief.

Security protocols. Guard rotations. Camera placement. Keycard levels. Motion sensors. Emergency exits. Where the blind spots were. When the facility ran on skeleton staff—between 3:00 and 6:00 a.m., when night shift paperwork lulled even vigilant men into predictable routines.

I learned a patrol pattern left certain areas unwatched for up to fifteen minutes.

Fifteen minutes isn’t long.

But it’s longer than you think when you’re desperate.

The juvenile wing was behind three security doors with escalating clearance. I had Level Two. It wasn’t enough.

Stealing a Level Four badge wouldn’t help, even if I could do it. The system logged every swipe—time, location, user.

Then I remembered something I’d seen maintenance workers use:

The tunnels.

Old service corridors under the building, originally built when the facility was a military bunker. Heating, cooling, power lines—an underground maze that connected to almost everything.

And the tunnels weren’t monitored like the main halls.

They had their own system, older, lazier, treated as infrastructure rather than a threat.

I spent two weeks mapping them.

I volunteered extra shifts. Came early. Stayed late. Walked past access points with purpose. Memorized routes. Found emergency exits that led outside the perimeter.

One night I nearly got caught studying a wall map in a maintenance room. I heard footsteps, ducked into a storage closet, and held my breath while a guard walked past, humming to himself.

That close call taught me a simple truth:

Planning is a kind of survival.

So I planned harder.

5) The Vehicle and the Lie of Normal

Transportation was the next problem.

Even if I could get the juvenile out, how do you move a six-foot, three-hundred-pound cryptid across four states without getting stopped?

You don’t.

Not in a normal car.

You need concealment. Space. Inconspicuousness.

I bought an old moving truck with cash. Rusted. Unremarkable. The kind of vehicle nobody remembers.

I registered it under a fake name using a fake address, counting on the DMV clerk’s boredom to do what bureaucracy does best: stamp and forget.

I parked it ten miles from the facility in a storage lot and stocked it slowly: blankets, tarps, rope, first aid, water, nonperishables, camping gear, maps, handheld GPS.

I even bought a small tranquilizer dart gun from a farm supply store and told the clerk I had aggressive raccoons.

I prayed I wouldn’t need it.

I also researched Bigfoot behavior obsessively—anything in the database that could help me keep the juvenile calm. Diet. Sleep cycles. Preferred foods. Responses to gestures.

The juvenile knew a few human words from cognitive tests. Not enough to explain what was happening.

So I practiced the gestures I’d seen adults use—open palms, slow movements, sweeping motions that signaled “come,” “safe,” “no threat.”

I felt ridiculous practicing in a mirror.

But desperation makes you humble.

The hardest part was acting normal while my life became a countdown.

Every day I smiled at colleagues. Took notes. Attended meetings. Poured coffee with shaking hands.

Nobody suspected me.

Why would they?

The idea of someone breaking a Bigfoot out of a federal facility was too absurd to be considered.

Absurdity is its own camouflage.

6) The Rain Night

I chose a Thursday in late October.

The forecast promised heavy rain and wind—noise cover, scent cover, fewer guards wandering outside. Thursdays were understaffed. The moon would be new. Maximum darkness.

The next day had a mandatory training session—people would be distracted and tired.

As close to perfect as I would ever get.

I arrived at work like it was any other day.

My stomach churned so hard I could barely eat. My hands shook pouring coffee. I forced myself to act bored, because bored people don’t look guilty.

Around lunch, I volunteered for an evening observation shift.

My supervisor approved it without hesitation.

At 6:00 p.m. the day shift left. By 8:00, skeleton crew. By 9:30, I walked toward the juvenile wing with a clipboard and binder like a faithful employee.

In the observation room, the juvenile sat in its usual corner, arms wrapped around knees, rocking slightly.

When it saw me, it lifted its head.

Those eyes.

Too aware.

Too tired.

For a second, I almost broke right there. Almost abandoned the plan out of fear.

Then I thought about the capture report.

And I moved.

First, cameras.

The juvenile wing’s camera system had a manual override in an electrical panel down the hall—a fail-safe for maintenance.

I flipped the switches for cameras 7 through 12.

The red recording lights winked out one by one.

Then I slipped into the storage closet at the end of the hallway, opened the tunnel access door, and climbed down.

The tunnels smelled like dust and machine heat. The air was stale. Pipes ran along the ceiling—some hot enough to burn you if you weren’t careful.

I navigated by flashlight and memory, heart hammering loud enough to feel like an alarm.

Five minutes. Maybe less. I reached the access hatch behind the juvenile enclosure.

I climbed slowly.

Opened the hatch into a small maintenance room.

Through a ventilation grate I could see the juvenile in the cell. It had heard something. Its head was tilted, listening.

I held my breath and pushed open the enclosure door.

The juvenile leaped up and backed into the far corner with a startled grunt, eyes wide with fear.

I raised my hands—open palms, low posture, slow movements.

I whispered nonsense soothing words. Tone mattered more than meaning.

Then I pulled an apple from my pocket and set it on the floor.

The juvenile’s eyes locked on it.

Fresh fruit was rare. The facility mostly fed paste and supplements. Apples meant something—comfort, memory, normal.

After a long moment, it crept forward, snatched the apple, retreated to its corner, and ate while watching me like I might change into a threat any second.

Good.

Curiosity was stronger than panic.

I spread a dark blanket on the floor. Pointed at it, then toward the door. Then pointed at myself.

Come. With me. Now.

I repeated the gesture, the adult-signals I’d practiced.

The juvenile hesitated, then stepped forward—one step, then another—until it was close enough to reach out and touch my arm.

Its hand was warm, fur soft, fingers long and dexterous.

Trust.

In that moment, I felt the strangest, sharpest pain—because trust from something you’ve helped imprison is both gift and indictment.

I wrapped the blanket around its shoulders like a cloak.

Up close, I saw scars and shaved patches from examinations. Too-thin ribs. A body that had grown inside concrete.

My resolve hardened into something cold and unstoppable.

We moved.

7) The Tunnels, the Door, the Sky

Getting it down the ladder into the tunnel system was the first real test.

It didn’t understand ladders. I demonstrated, climbed partway down, gestured.

It watched closely. Studied. Then tested with one foot, one hand, like a mind solving a puzzle.

Within seconds it had it.

That intelligence again—quiet, frightening, beautiful.

We moved through the tunnels fast, stopping to hide behind pipes when we heard voices above. Each time the juvenile froze completely still, barely breathing.

It understood sneaking.

It understood danger.

Finally, we reached the emergency exit I’d prepared: a service door to the back perimeter.

It was supposed to be alarmed. I’d disabled the alarm earlier in the week, logging it as a malfunction.

No one had verified.

I pushed the door open.

Rain slammed the world. Wind howled through trees.

The juvenile hesitated at the threshold, looking up at the open sky like it was seeing God.

Then it stepped out.

And for a second, it didn’t look like an experiment.

It looked like a child returning to something it had almost forgotten existed.

I tugged gently on the blanket.

We ran.

A quarter mile to the truck, hidden behind a maintenance shed. The rain washed our tracks away as quickly as we made them.

The juvenile guided me around obstacles I couldn’t see—drainage ditches, logs, slick mud.

At the truck, it sniffed suspiciously at the metal box. I climbed into the cargo area first, sat on the blankets, patted the space.

After a moment, it ducked inside and settled into a corner.

I gave it another apple.

Then I closed the door.

Locking it felt like betrayal.

But a visible Bigfoot on a highway would be a death sentence.

I climbed into the driver’s seat, started the engine.

The truck coughed, sputtered, then caught.

I drove.

No headlights behind me. No sirens.

Phase one was complete.

Phase two was survival.

8) Four States of Fear

I avoided highways. Back roads. Rural routes. No tolls, no cameras if I could help it.

Rain turned to sleet in mountain passes. The heater barely worked. I didn’t stop.

Once the facility discovered the juvenile was gone, every law enforcement agency in the region would be spun into motion, even if the public story stayed vague.

Around 4:00 a.m., I pulled into a rest stop to check on it.

I knocked before opening, because I didn’t want to trigger panic.

It was awake, sitting up, watching the door.

When it saw me, it made a soft hoot—curious, not hostile.

That sound did something to me. It felt like the first time in months I could breathe.

I brought fruit and water. Gestured “long way,” “still going.”

It seemed to understand enough.

By dawn, Idaho.

At a gas station, I paid cash and noticed a news ticker in the convenience store:

THEFT OF CLASSIFIED MATERIAL FROM FEDERAL FACILITY…

They knew.

But they wouldn’t say what was stolen.

They couldn’t.

Admitting they’d been holding Bigfoots would crack the world in half.

So they’d hunt me quietly.

And if they caught me, the juvenile would vanish into a deeper cage.

I drove harder.

The next thirty hours blurred into a fever dream of gas stops, parking lot naps, and the constant awareness of a living secret breathing behind me.

The smell became a problem—musky, earthy, wild. Not unpleasant, but strong. I bought cedar shavings used for horse bedding and spread them in the cargo area.

It helped.

Not enough.

But enough to keep most humans from asking questions they didn’t want answers to.

Bathroom breaks were… creative.

Every few hours I found remote pull-offs: logging roads, abandoned campgrounds, empty rest areas. The juvenile would climb out, vanish into trees, return when I called.

Always returned.

It understood that together was safer.

By the time we reached Washington, I was exhausted—three days of driving, my mind fraying at the edges. I started seeing movement that wasn’t there. Jerking awake from micro-sleeps with my hands still on the wheel.

But we were close.

Less than a hundred miles to the North Cascades.

And then the roads ended.

9) Into the Real Wilderness

I parked at a secluded campground on the forest edge. The moving truck looked like any other junker. Nobody paid attention.

That night, I let the juvenile out for a few hours.

It explored like someone waking from a long sickness—touching trees, sniffing rocks, looking up at stars as if the sky itself was a forgotten language.

It climbed a pine tree with effortless grace and hooted softly from the branches.

For the first time, I saw joy on it.

Not contentment.

Joy.

And it nearly broke me, because it proved exactly how much we had stolen by keeping it in concrete.

The next morning I packed a backpack: water, food, first aid, emergency shelter, GPS, maps, the dart gun.

Fifteen miles into the national forest, according to the files. Two days, maybe more.

The juvenile hesitated at the treeline, looking between me and the mountains.

I used the gestures again.

Come. This way. Trust me.

After a long moment, it followed.

It moved nearly silent on moss and needles, alive in the forest in a way it never had been in captivity. It stopped to examine mushrooms, nests, bark. It steadied me when I stumbled, like it had become my guide without either of us deciding it.

Around midday on day two, I found markers.

Twisted pine saplings bent at unnatural angles—alive but shaped, scarred but not broken. A line of them leading deeper into the valley like breadcrumb signals.

The juvenile touched the bark and made excited sounds.

Recognition.

It started following the markers without prompting, moving with purpose.

By sunset, we reached a clearing with an old nest built into the crook of trees—ten feet across, woven branches, bedding of leaves and moss.

A Bigfoot nest.

Abandoned.

The juvenile climbed into it anyway, touching the structure gently, sniffing old bedding like it was looking for the scent of memory.

Then it made soft, mournful sounds.

Doubt hit me like cold water.

What if they’d moved?

What if the files were outdated?

What if I’d brought it all this way to nowhere?

That night, the juvenile called into the dark—long, complex sounds rising and falling like a song.

I lay in my tent listening, praying for an answer.

For a long time: nothing.

Then, just as sleep started to pull me under, a distant call answered back—deeper, more powerful, from somewhere north.

The juvenile responded instantly, excited, almost shaking.

Call and response.

Language.

They were here.

10) The Reunion in the Stream

At dawn, the juvenile moved with urgency, leading me. Faster now. Certain.

We climbed to a rocky outcrop above a ravine and saw fresh tracks by a stream below—adult-sized, new enough to be meaningful.

We descended.

The juvenile tracked like a trained hunter—examining bent grass, scuffs, broken twigs, adjusting direction with tiny shifts. It was reading a story I could barely see.

Hours later, we rounded a bend, and it froze.

I froze too.

In the stream ahead, an adult Bigfoot stood washing something—fish, roots, I couldn’t tell. Eight feet tall, dark fur wet and nearly black, shoulders like boulders.

It lifted its head.

Sniffed.

And turned toward us.

My fear was immediate and primal. This was not a fairy tale. This was a wild creature in its territory, and I was standing beside a juvenile that might not be recognized as family.

My hand tightened on the dart gun in my pack—useless comfort.

Then the juvenile stepped forward and vocalized—complex hoots, clicks, grunts, patterned like speech.

The adult went still, head tilted.

Then it responded.

Back and forth. Minutes of communication I couldn’t understand but could feel in the tension of their bodies.

Then the adult dropped what it was holding and charged toward us.

I grabbed for the dart gun—

And the juvenile ran forward too.

They collided in the stream.

Not an attack.

An embrace.

The adult wrapped its arms around the juvenile and made deep rumbling sounds that vibrated through my chest. The juvenile made high, broken sounds that were too close to crying for me to pretend they were anything else.

Water rushed around their legs.

And I cried, because the moment was so simple it hurt:

A child came home.

After the reunion, the adult finally looked at me.

Those eyes—intelligent, weary, assessing.

I raised my hands, open palms, lowered my posture, avoided direct stare.

The juvenile vocalized again, gesturing between me and the adult—telling a story.

The adult listened.

Then made a soft grunt—not friendly, not hostile.

Acceptance.

Then the adult whooped loud enough to shake my ribs.

Within minutes, more Bigfoots appeared—two adults and another juvenile—forming a semicircle around me.

I felt the pure animal fear of being surrounded by beings that could erase me with one decision.

But the rescued juvenile stayed near me, touching my arm occasionally, as if reassuring the others: This one helped.

They examined the juvenile I brought—sniffing, touching scars, running hands over shaved patches and too-thin ribs. One adult—likely the mother—made distressed sounds at every sign of suffering, fingers trembling slightly as she traced marks left by captivity.

Then she turned toward me.

She stepped close enough that I could feel the heat of her body, smell that earthy wild scent.

And she touched my face gently with her huge hand.

Not possession.

Not threat.

Recognition.

The juvenile vocalized rapidly, urgent—story spilling out of a throat that had once begged into glass.

The mother listened.

Her expression changed.

Then she touched her chest, touched mine, and pointed at the juvenile.

Thank you.

There is no other translation that fits.

I nodded, touched my own chest, then gestured toward the child and toward the forest: home.

She made a sound like a sigh.

Then she turned and led the group away.

The juvenile followed, but kept looking back. After twenty feet, it stopped and turned fully toward me.

We stared at each other across distance.

Then it lifted one hand, fingers spread—almost a wave.

I waved back.

The mother made an urgent sound.

The juvenile turned and ran, catching up.

They vanished into the trees.

And I was alone again.

But the loneliness felt… different.

Like the clean ache after doing something that costs you but doesn’t poison you.

11) The Price of Freedom

The hike back took three days.

Without the juvenile guiding, I got lost twice. My feet blistered. My cough worsened. I ate the last of my food and kept moving because stopping felt like inviting the past to catch up.

When I reached the campground, my truck was still there.

No agents.

No waiting cars.

Just rust and silence.

I drove south, stayed off-grid, ditched the truck at a junkyard in Oregon for two hundred dollars cash. Hitchhiked into California.

I became nobody.

For weeks I watched the news, waiting for my face on a screen, my name in a headline.

Nothing.

The facility reported “classified material theft.” No details.

They couldn’t admit what I took.

Admitting it would raise questions they couldn’t answer without unraveling entire programs.

So they let me vanish.

Or they searched quietly and simply failed.

Either way, I didn’t go back.

That life—my lab coat, my badge, my career—was over.

And I didn’t miss it the way you’d think.

Because once you’ve seen a child behind glass, you stop caring about promotions.

12) The Basket

Two years after the escape, I was working fence repair on a ranch in Northern California.

Quiet job. Cash pay. No questions.

One morning, at the far pasture fence, I found something waiting on a post:

A small woven basket made from bark and pine needles.

Inside: wild berries and roots, arranged neatly—berries on one side, roots on the other, separated by leaves.

Too deliberate to be chance.

Too complex to be human prank.

My heart started pounding.

The weaving pattern matched what I’d seen in Bigfoot nest construction—over-under, tight and functional.

A gift.

A message.

I looked around. No tracks. No signs. Just cattle grazing peacefully.

But I knew what it meant:

Someone remembered.

Maybe the juvenile. Maybe the mother. Maybe another from that family.

Maybe they’d followed me for a while and decided, carefully, to let me know I wasn’t forgotten.

I took the basket home and put it on the shelf above my bed.

Not as proof. Not as trophy.

As a reminder that what I did mattered.

That a life was returned to where it belonged.

That an act of mercy echoed back across a gulf most people refuse to believe exists.

13) What I Can’t Fix

I still think about the adults left behind.

Part of me wants to go back. I dream about it sometimes—opening every cell, watching concrete gods run into rain and vanish into trees.

But I know reality.

The facility will have increased security. Lightning doesn’t strike twice. Adult Bigfoots would be harder to transport, harder to calm, less likely to trust.

Some cages can’t be opened by one person with a conscience.

That’s the hardest part of all: knowing what’s still happening and being unable to tell anyone without exposing the very beings you want to protect.

I can’t go to the media. I can’t go to animal rights groups. I can’t publish proof without building a beacon that hunters, profiteers, and governments would follow straight into the last safe places.

So I do the only thing I can do:

I tell the story without names. Without coordinates. Without a map to ruin them.

And I ask whoever reads this to consider a simple idea:

If Bigfoot are real—and if they think and feel the way I know they do—then captivity isn’t research.

It’s cruelty dressed in a lab coat.

And if you ever find yourself in deep wilderness, and you feel the forest go quiet, and you sense you’re being watched by something older than your certainty—do not chase it.

Do not try to prove it.

Back away.

Let it live.

Because freedom is not a gift humans give the wild.

Freedom is what the wild has always had—until we decided everything must belong to us.

I stole a child back from that decision.

And I will carry that truth, like a weight and a flame, for the rest of my life.