The intake officer at the United States prisoner of war camp in rural Georgia watches a transport truck pull up in the late afternoon heat of April 1945. The guards shout orders in English. The prisoners stumble out one by one, blinking against the sunlight, filthy and hollow wide from the Atlantic crossing and the rail journey south.

Then a boy appears at the back of the truck, thin and pale. And when he tries to step down, his legs buckle. Two guards catch him before he hits the dirt. The camp medic is summoned. He runs his hands over the boy’s torso and stops. He feels something hard under the skin, then another lump and another. The medic looks up at the officer and says five words that will change everything in that camp.

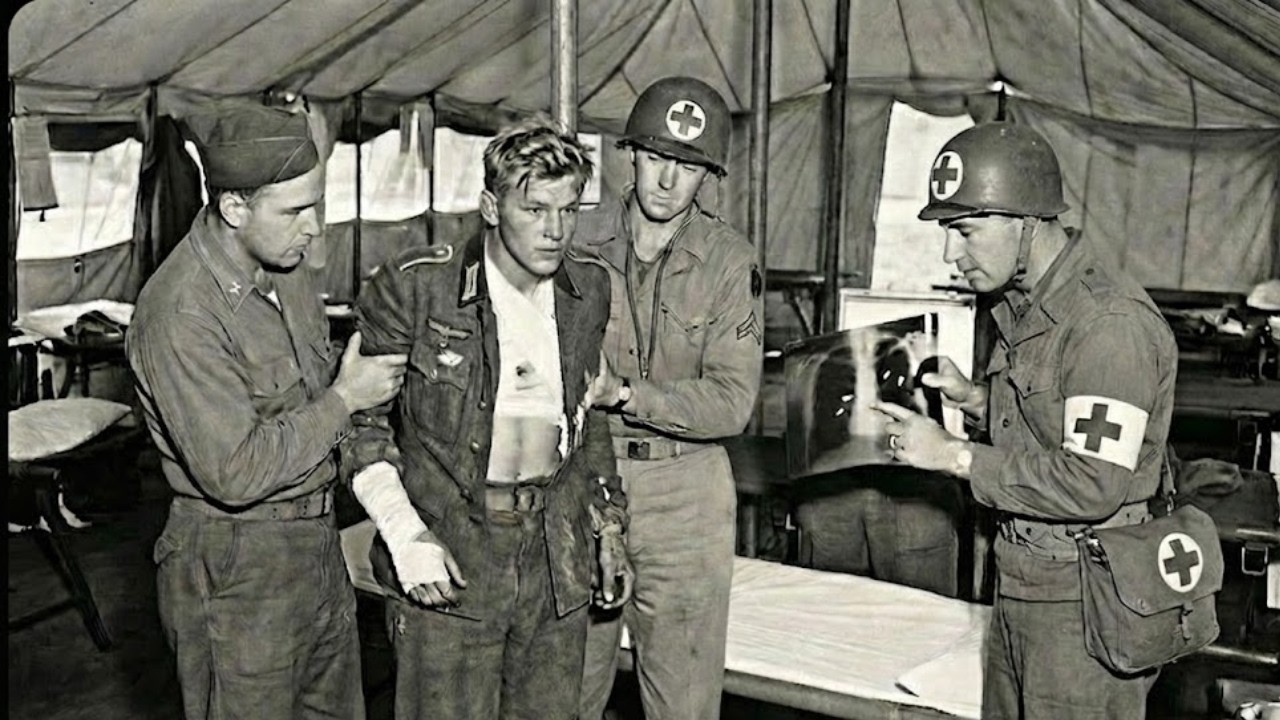

This boy has metal inside him. We are in a processing tent at a United States Army prisoner of war camp in Georgia in the spring of 1945. The war in Europe is nearly over, but the camps are still receiving prisoners from the final battles. Now, we are about to meet the youngest arrival in this particular convoy, a boy who carries wounds that nobody expected to see.

His name is Klaus Hoffman, though the intake clerk will misspell it three different ways on the paperwork. He is 19 years old. He weighs 108 lb. He has been a soldier for less than 2 years and a prisoner for less than 2 weeks. The medic orders Klaus to remove his shirt. The fabric is stiff with sweat and dirt, and when it comes off, the smell makes the guard step back.

Klaus’s ribs are visible through pale skin, but that is not what shocks the medic. There are five small scars scattered across his chest, back, and left shoulder. They are old wounds, partially healed, but raised and angry. The medic presses gently on one of the scars, and Klouse flinches. The medic feels the unmistakable shape of metal under the skin.

He moves to the next scar and finds the same thing. Then the third, then the fourth, then the fifth. Five pieces of shrapnel are still embedded in this boy’s body and somehow he is still standing. The camp doctor is called immediately. He arrives within 10 minutes. A veteran surgeon named Captain Robert Lawson, who has seen more combat wounds than he cares to remember.

He examines Klaus in silence, palpating each site carefully, checking for signs of infection or internal damage. Then he asks Klaus a question in broken German. When were you wounded? Klouse answers in even worse English. January. The doctor does the math. That means Klouse has been carrying these fragments for more than 3 months.

He has survived combat, capture, interrogation, transport across the Atlantic, and a week in a holding facility, all with five pieces of enemy metal lodged in his body. The doctor looks at the intake officer and says something that will echo through the camp for weeks. This boy should be dead. We are still in the camp hospital tent moments after the initial examination.

Now, we go back to how Klouse received these wounds and why they were never treated. The timeline starts in January 1945 in the frozen chaos of the Western Front. Klouse was part of a Vogs Granadier division, one of the hastily assembled infantry units Germany threw together in the final months of the war. These divisions were filled with teenagers, old men, and anyone else the regime could conscript.

Klaus had been in uniform for 8 months. He had never fired his rifle in anger until December 1944. His unit was positioned near a small town in western Germany, trying to hold a defensive line against advancing American forces. The orders were simple and impossible. Hold the line. Do not retreat.

There was no air support, no artillery, and barely enough ammunition for one firefight. On the morning of January 14th, American tanks appeared on the ridge to the east. Klaus and his squad were ordered to dig in and prepare for an assault. They had no anti-tank weapons. They had no reinforcements. They had no chance. The American bombardment began at dawn.

The shells came in waves, walking across the frozen fields and smashing into the German positions. Klaus pressed himself into the bottom of his foxhole and prayed. The shell that nearly killed him landed 5 m away. The explosion lifted Klaus off the ground and slammed him back down into the dirt. He could not hear anything except a high-pitched ringing.

He tried to move and felt sharp pain in his chest, his back, and his shoulder. He looked down and saw blood spreading across his uniform. He did not know how many pieces of metal had entered his body. He only knew that he was still breathing and that he needed to get out of that foxhole before the next shell hit.

He crawled 20 m to a drainage ditch, dragging his rifle behind him. Two other soldiers were already in the ditch, both wounded, both silent. One of them looked at Klouse and shook his head. The message was clear. You are not going to make it. We are now moving forward in time from the moment Klaus was wounded to the moment he was captured.

This is the part of the story that explains why a German field hospital never removed the shrapnel and why Klaus was forced to carry it across Europe and the Atlantic. The answer is not medical. It is logistical and it is brutal. By January 1945, the German military medical system in the West had collapsed. There were not enough doctors, not enough morphine, not enough surgical instruments, and not enough time.

Wounded soldiers were triaged in minutes. If you could walk, you were sent back to the line. If you could not walk but might survive, you were loaded onto a truck and sent east toward a field hospital that probably did not exist anymore. If you were going to die, you were left where you fell. Klouse was triaged by a medic who spent less than 30 seconds examining him.

The medic checked for bleeding arteries and collapsed lungs. He found neither. The shrapnel had missed every vital organ by centimeters. The wounds were painful, but not immediately fatal. The medic wrapped Klouse in a dirty bandage, gave him a canteen of water, and told him to report to the regiment assembly 3 km west. Klouse asked about surgery.

The medic laughed. There is no surgery. There is no hospital. If you can walk, you walk. Klouse walked. He walked for two days, sleeping in barns and abandoned houses, eating nothing, drinking from streams. He reached the assembly point and found chaos. The regiment no longer existed as a functioning unit.

There were scattered squads, leaderless and desperate, trying to avoid American patrols. Klouse attached himself to a group of six other soldiers. None of them had a plan. They just kept moving west. On January 23rd, 9 days after Klaus was wounded, his group stumbled into an American checkpoint. They were exhausted, starving, and unarmed.

They surrendered without a fight. The American soldiers searched them, took their identification papers, and loaded them onto a truck. Klouse was now a prisoner of war. He still had five pieces of shrapnel in his body. He still had not seen a doctor. He did not know if he ever would. Let us know in the comments where you are watching this from.

Are you in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, or somewhere else. We would love to know who is keeping these stories alive. What Klaus did not know as he sat in the back of that truck was that his wounds were about to become the center of a medical and ethical debate that would divide an entire camp. We are now in February 1945 and Klouse is part of a massive prisoner transport operation that will take him from Europe to the United States.

This is the journey that nearly killed him three separate times, not from his wounds, but from the conditions of the transport itself. The first stage was a holding camp in France, a sprawling facility near Cherborg where thousands of German prisoners waited for ships. Klaus spent two weeks there. He was given a medical inspection that lasted less than 5 minutes.

The American medic asked him if he had any injuries. Klouse lifted his shirt and pointed to the scars. The medic shrugged and marked him as ambulatory. That was the end of the examination. The ship that took Klaus across the Atlantic was a converted cargo vessel retrofitted with bunks and sanitation facilities that barely functioned.

Klouse was assigned to a compartment below deck with 80 other prisoners. The air was thick and hot. The smell was unbearable. Men vomited constantly from seasickness. Others developed dysentery and could not make it to the latrines in time. Klouse spent most of the voyage lying on his bunk trying not to move because every movement sent sharp pain through his chest and shoulder.

The shrapnel fragments were shifting inside him, grinding against bone and tissue. He was certain that one of them would puncture something vital and he would die in that compartment, surrounded by strangers thousands of miles from home. The crossing took 12 days. Klouse lost another 10 lbs. When the ship docked in New York, he could barely stand.

He was loaded onto a train with 200 other prisoners and sent south. The train journey took three days. Klouse remembers almost nothing from that trip except the sound of the wheels on the tracks and the constant grinding pain in his shoulder. When the train finally stopped and the doors opened, Klouse stepped out into the Georgia heat and collapsed.

That is when the medic caught him. That is when the metal was discovered. That is when his story stopped being just another prisoner transport and became something that the camp staff would talk about for months. We are taking a brief pause in Klaus’s story to understand the scale of the prisoner of war system in the United States during World War II.

These numbers will help explain why Klaus’s case was so shocking and why it forced the camp staff to confront problems they had been ignoring. Between 1943 and 1945, the United States held more than 400,000 German prisoners of war in camps across the country. These camps ranged from small work details of 50 men to massive facilities holding 10,000 or more.

The camp where Klaus arrived held approximately 2,000 German prisoners at any given time. It was considered a midsize facility, neither particularly harsh nor particularly lenient. The medical staff at this camp consisted of one doctor, Captain Lawson, two medics, and a rotating crew of prisoner volunteers who had medical training.

They were responsible for treating everything from minor injuries to serious illnesses. The camp hospital had 20 beds, basic surgical equipment, and a limited supply of antibiotics. The rules governing medical treatment for prisoners of war were clear. Prisoners were entitled to the same standard of care as American soldiers.

In practice, this rule was inconsistently applied. Prisoners with life-threatening conditions receive treatment. Prisoners with chronic pain or minor ailments often did not. Klouse’s case fell into a gray area that nobody wanted to define. If you are enjoying this story and want more untold accounts from World War II prisoners of war, make sure to subscribe to the channel.

We are bringing you stories that most history books never covered. The shrapnel inside Klouse was not immediately life-threatening, but it was causing constant pain and slowly increasing the risk of infection. Removing it would require surgery, anesthesia, and a week of recovery. That meant taking up hospital resources, medical staff time, and supplies.

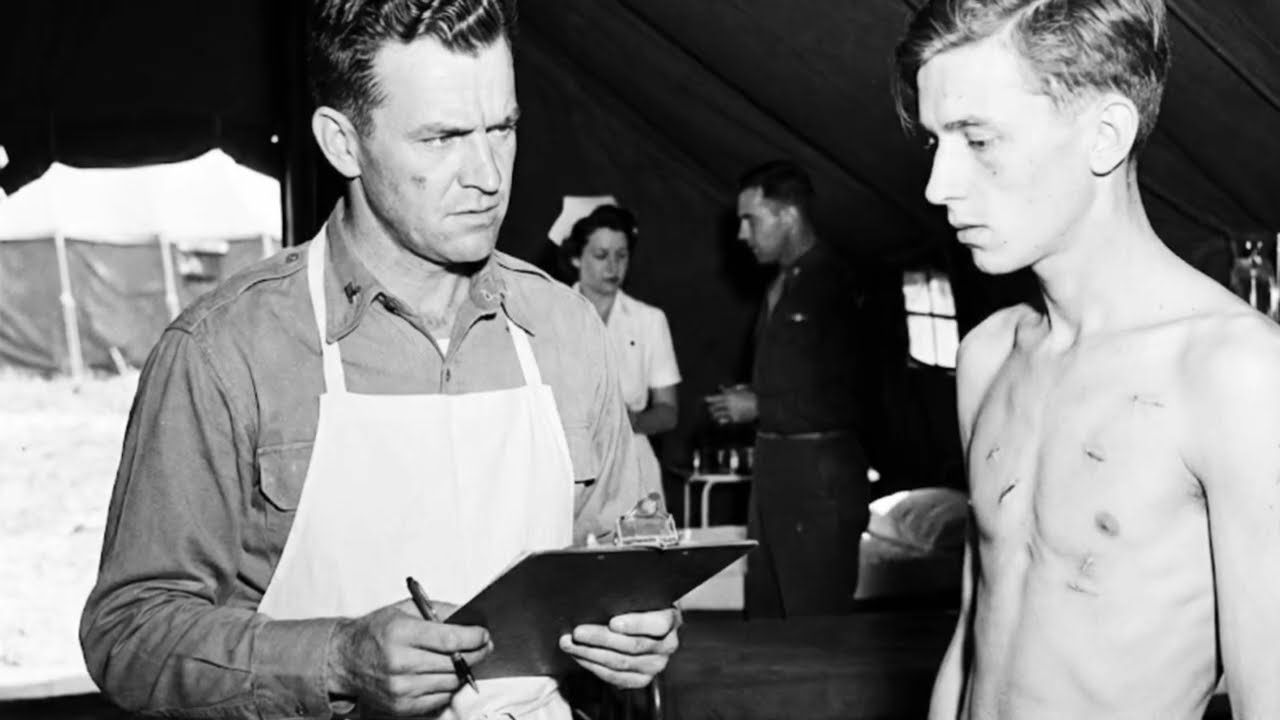

Some officers in the camp argued that Klouse should be treated immediately. Others argued that he should wait until the war ended and German hospitals could handle it. The debate exposed a deeper question that nobody wanted to answer out loud. How much care do we owe to a boy who was until a few weeks ago trying to kill us? We are back in the camp hospital and Captain Lawson has made his decision.

He will operate. He will remove as many shrapnel fragments as he can safely extract and he will do it within the next 48 hours. The decision is not popular. The camp commander, a colonel named Harris, tells Lawson that he is wasting resources on a prisoner who will be repatriated in a few months anyway. Lawson responds with a sentence that ends the debate.

If we let this boy die from an infection we could have prevented, we are no better than the people we are fighting. Harris does not argue further. The surgery is scheduled for April 21st, 1945. Klouse is told about the surgery through a translator, a German-speaking prisoner who works in the camp administration office. Klouse asks two questions.

Will it hurt? Will I survive? The translator does not sugarcoat the answers. Yes, it will hurt. Probably you will survive. Klouse nods. He has no other options. He is taken to the hospital the night before the surgery and given a bed in the corner of the ward. He does not sleep. He stares at the ceiling and thinks about his mother, who has not heard from him in 4 months and probably believes he is dead.

He thinks about the foxhole in January and the shell that should have killed him and the strange luck that has kept him alive this long. He wonders if that luck is about to run out. The surgery begins at 8:00 in the morning. Lawson uses local anesthesia because the camp does not have enough general anesthesia to spare for a prisoner.

Klouse is awake for the entire procedure. He can feel pressure and tugging, but not sharp pain. Lawson works methodically, making small incisions over each fragment and using forceps to extract the metal. The first piece comes out easily. a jagged shard the size of a thumbnail. The second and third pieces are deeper and require more cutting.

The fourth piece is lodged against Klaus’s shoulder blade and takes 15 minutes to remove. The fifth piece is the worst. It is embedded in the muscle near Klaus’s spine, and Lawson has to go in at an angle to avoid damaging nerves. Klouse grits his teeth and does not scream. When it is finally over, Lawson holds up five pieces of shrapnel on a metal tray.

Klouse stares at them and starts to cry. We are now in the days following the surgery, and Klouse is recovering in the camp hospital. The operation was a success. All five fragments were removed. The wounds were cleaned and stitched, and there are no signs of infection. Klouse is in pain, but it is a different kind of pain, cleaner and more manageable.

For the first time in three months, he can move his shoulder without feeling metal grinding against bone. He sleeps for 14 hours straight after the surgery. When he wakes up, he asks for food. The nurse, an American medic named Corporal Jensen, brings him broth and bread. Klouse eats slowly, savoring every bite. But not everyone in the camp is happy about Klaus’s treatment.

Some of the guards resent the fact that a German prisoner received surgery while American soldiers are still fighting and dying in Europe. Some of the other prisoners resent Klouse because they see him as receiving special treatment. One prisoner, a former Vermach officer, confronts Klouse in the hospital and accuses him of collaborating with the Americans. Klouse does not respond.

He is too tired to argue and he knows that resentment is just another kind of wound, one that cannot be removed with surgery. The officer walks away muttering something about traitors and cowards. Captain Lawson visits Klouse every day to check the stitches and monitor for infection. On the third day, he brings a small cloth bag and hands it to Klouse.

Inside are the five pieces of shrapnel cleaned and wrapped in gauze. Lawson says something in English that the translator repeats in German. You carried these for three months. You earned them. Klaus does not know what to say. He holds the bag and feels the weight of the metal and he realizes that these fragments are the only proof he has of what he survived.

He thanks Lawson in halting English. Lawson nods and leaves. That night, Klouse tucks the bag under his pillow and sleeps without nightmares for the first time since January. We are moving forward several weeks now, and Klaus’s surgery has created ripples throughout the camp that nobody anticipated. Other prisoners begin coming forward with medical complaints they had been hiding or ignoring.

One man has a broken finger that healed crooked. Another has a persistent cough that turns out to be early stage tuberculosis. A third has an infected wound on his leg that he has been treating with rags and hope. Captain Lawson finds himself overwhelmed with patience, but he does not turn anyone away. He realizes that Klaus’s case has opened a door, and that door cannot be closed without betraying the principles that justified the surgery in the first place.

The camp commander, Colonel Harris, is furious. He accuses Lawson of creating a precedent that will drain the camp’s medical resources and set a dangerous example for other facilities. Lawson does not back down. He argues that treating prisoners humanely is not just a legal obligation. It is a strategic advantage.

Healthy prisoners are easier to manage, less likely to cause trouble, and more willing to cooperate with camp authorities. Harris is not convinced, but he does not override Lawson’s decisions. The medical treatments continue. By the end of May, Lawson and his team have performed minor surgeries on 12 prisoners, treated infections in 30 more, and identified three cases of serious illness that required transfer to a civilian hospital.

Klouse becomes a strange kind of symbol in the camp. To the Americans, he represents the complexity of the enemy, a reminder that the faceless Vermacht includes boys who never wanted to fight. To the other prisoners, he represents something more complicated, a mix of luck, survival, and the uncomfortable reality that their capttors are capable of mercy.

Klouse does not ask to be a symbol. He just wants to heal, to eat regular meals, and to survive long enough to go home. But symbols are not chosen. They are assigned. And Klouse, whether he likes it or not, has become a story that the camp will tell long after the war ends. We are now in early May 1945, and the war in Europe is over.

Germany has surrendered. The camps in the United States are no longer receiving new prisoners, but they are still holding hundreds of thousands of men who cannot go home yet. The infrastructure in Germany is destroyed. The occupation zones are still being organized. Repatriation will take months, possibly years.

Klouse is healthy enough to leave the hospital and return to the general prisoner population, but he is not strong enough for heavy labor. He is assigned to light duties, mostly kitchen work and cleaning. He does not complain. He is alive, fed, and safe. That is more than he expected four months ago. The mood in the camp shifts after the surrender. Some prisoners are relieved.

Others are bitter and angry, convinced that Germany was betrayed from within. A few cling to fantasies of a lastminute reversal, a secret weapon, a miracle that will change everything. Klouse listens to these conversations, but does not participate. He has no interest in politics or blame.

He just wants to know when he can leave. The answer when it finally comes is frustrating. Nobody knows. The camp administration has no timeline for repatriation. The prisoners are told to wait, to work, and to follow the rules. Waiting becomes the hardest part of captivity. Klouse writes letters home even though he has no idea if they will ever be delivered.

He writes to his mother, to his younger sister, to an uncle who might still be alive. He does not write about the shrapnel or the surgery. He writes about the weather, the food, the strange kindness of the American doctor. He tries to sound optimistic, but he does not feel optimistic. He feels suspended, trapped between a war that is over and a peace that has not yet arrived. Months pass.

Summer turns into fall. The camp population slowly decreases as small groups of prisoners are processed and sent back to Europe. Klouse is not in any of the early groups. He waits. We are now in early 1946, almost a full year after Klouse arrived at the camp. He is finally told that his repatriation has been approved.

He will leave in 2 weeks as part of a convoy heading to New York where he will board a ship back to Europe. Klaus feels relief, but also fear. He does not know what he is going back to. His hometown is in the Soviet occupation zone. His family may have been displaced or worse. The Germany he left in 1944 no longer exists.

He is going home to a country that has been defeated, occupied, and divided. But it is still home, and he needs to see it. On his last day in the camp, Captain Lawson visits him one final time. He brings a small envelope and hands it to Klouse. Inside is a medical report written in English and German documenting the surgery and the removal of the shrapnel.

Lawson tells Klouse to keep it in case he ever needs proof of what happened to him. Klaus thanks him again and this time he does not struggle with the English. He has learned enough over the past year to express simple gratitude. Lawson shakes his hand and wishes him luck. Klouse boards the truck with 40 other prisoners and the camp disappears behind him.

The journey back to Europe takes three weeks. Klaus arrives in Braymond in February 1946, almost exactly one year after he left. He is processed through a displaced person’s camp, given a small amount of money, and released. He travels east by train and on foot, moving through a landscape of ruins and refugees.

He reaches his hometown in early March. The house where he grew up is still standing, but it is occupied by strangers. His mother and sister are gone. A neighbor tells him that they fled west ahead of the Soviet advance. The neighbor does not know where they went. Klouse stays in the town for 2 days asking questions and finding no answers. Then he leaves and heads west.

We are moving forward now into the postwar years and the historical record on Klaus Hoffman becomes fragmented and incomplete. There are no detailed accounts of his life after 1946. only scattered traces in displacement records, refugee registries, and a single interview conducted in the 1980s. What we know is limited, but it is enough to sketch the outline of what happened to him.

Klouse eventually found his mother and sister in a refugee camp in Bavaria in late 1946. They had survived the war, but lost everything else. Klouse worked a series of manual labor jobs, helping to clear rubble and rebuild infrastructure in the British occupation zone. He never talked about the shrapnel or the surgery, at least not in any recorded conversation.

In the 1950s, Klouse married and started a family. He worked as a mechanic, a trade he learned during his time in the displaced person system. He lived a quiet life, avoiding attention and avoiding the past. The only physical evidence of his wartime experience was a set of scars on his chest and shoulder and a small cloth bag containing five pieces of shrapnel that he kept in a drawer and never showed anyone.

In the 1980s, a local historian researching prisoner of war experiences tracked Klouse down and convinced him to give an interview. Klouse was in his 50s by then, balding and soft-spoken. He answered questions about the camp, the surgery, and the doctor, but he did not elaborate. He said the past was the past, and he preferred to leave it there.

Klaus Hoffman died in 1998, 2 years after his wife. He was 72 years old. His children found the cloth bag among his belongings and did not know what it was until they read the old medical report that Captain Lawson had given him. The shrapnel and the report are now part of a small regional museum in Bavaria displayed alongside other artifacts from the war.

There is a placard that explains Klaus’s story in three short paragraphs. It does not mention the fear, the pain, or the strange mercy of an American doctor who decided that a wounded enemy boy deserved to be saved. It just says that Klaus Hoffman was a soldier, a prisoner, and a survivor. Sometimes that is enough.

We are stepping back now to examine what Klaus’s story tells us about the larger prisoner of war system in the United States during World War II. His case was unusual, but it was not unique. Thousands of German prisoners received medical treatment in American camps, ranging from routine care to complex surgeries. The quality and availability of that care varied widely depending on the camp, the staff, and the attitudes of the commanding officers.

Some camps treated prisoners as a logistical burden to be managed with minimal resources. Other camps, like the one where Klouse was held, treated prisoners as human beings who deserved basic dignity and medical care. The difference often came down to individual decisions made by individual doctors and officers. The legal framework governing prisoner treatment was established by the Geneva Conventions, which required captors to provide medical care equivalent to what they provided for their own troops.

In practice, this standard was interpreted flexibly. Prisoners with life-threatening conditions almost always received treatment. Prisoners with chronic conditions or minor ailments often did not. The moral and ethical debates that surrounded Klaus’s surgery played out in camps across the country with no clear consensus.

Some officers believed that generosity toward prisoners was a strategic advantage, fostering cooperation and reducing resistance. Others believed it was a waste of resources that should be reserved for American soldiers. What makes Klaus’s story significant is not that he received care, but that his care became a catalyst for broader change within his camp.

Captain Lawson’s decision to operate on Klouse forced the camp administration to confront the gap between official policy and actual practice. It also forced other prisoners to recognize that they could seek help without being dismissed or punished. The ripple effects of that one surgery lasted for months, improving conditions and saving lives.

It is impossible to know how many other prisoners benefited indirectly from Klaus’s case, but the number is almost certainly higher than zero. In that sense, Klaus’s survival was not just a personal victory. It was a small quiet triumph of humanity over the machinery of