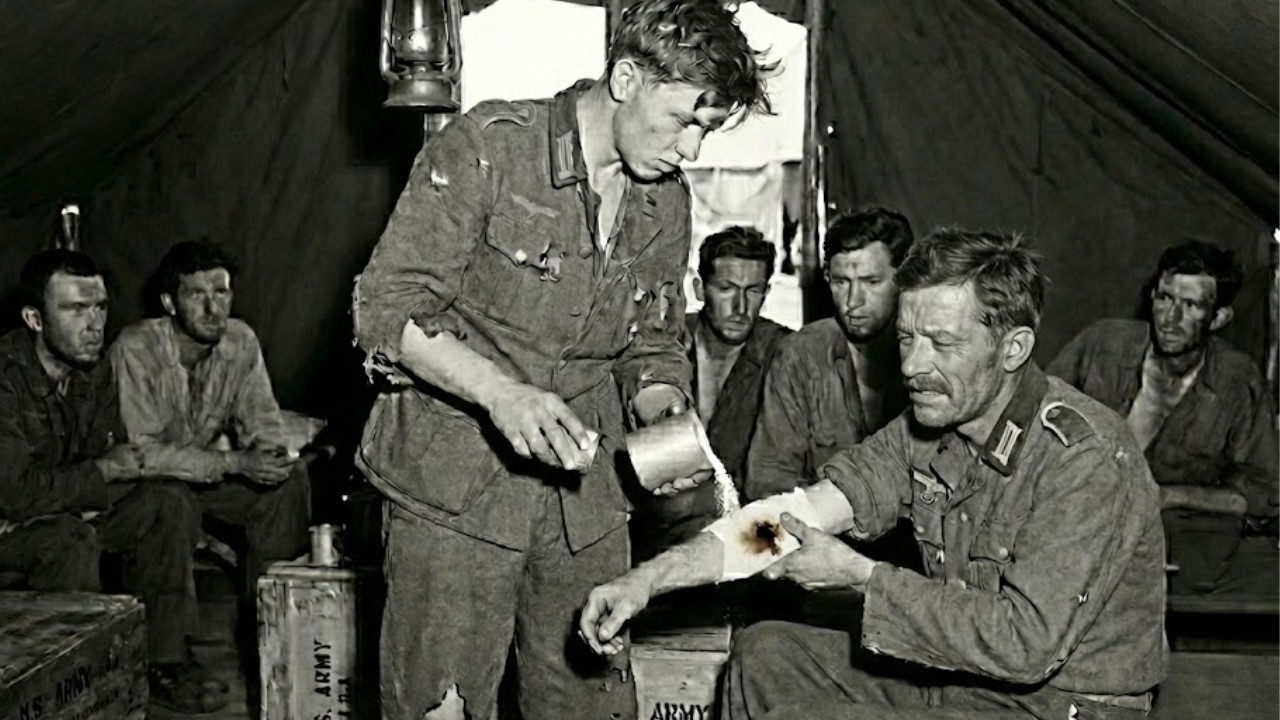

The prisoner is mixing powdered milk with water in a metal canteen and telling sick prisoners to drink it. The camp doctor, Captain Michael Stevens, walks into the barracks and sees this happening. Stevens asks what the prisoner is doing. The prisoner’s name is Ernst. He is 19 years old. He says in broken English that the milk mixture will stop the dysentery.

Steven says that is insane. Milk products make diarrhea worse, not better. Everyone knows this. Giving milk to prisoners with dysentery will kill them faster. But Ernst insists the mixture works. He learned it from his grandmother who ran a dairy farm in Bavaria. Stevens tells Erns to stop immediately. Ernst refuses. He says 52 prisoners in this barracks have dysentery and six have already died.

The camp hospital has no medicine to treat them. Ernst’s milk mixture is their only chance. Stevens faces a decision. Shut down Ernst’s treatment and watch more prisoners die or allow an unproven folk remedy that might make everything worse. What Stevens discovers over the next week shocks everyone at Camp Alva and changes how dysentery outbreaks are treated.

We are at Camp Alva in Oklahoma in August 1943, 13 months after the United States entered World War II. The camp holds approximately 3,000 German prisoners of war, mostly captured in North Africa during the Tunisia campaign. The climate in Oklahoma is brutally hot in August with temperatures exceeding 100° most days.

The heat creates perfect conditions for bacterial growth and disease transmission. In late July, a dysentery outbreak begins in barracks 12, spreading rapidly through the prisoner population. Dysentery is a severe intestinal infection causing bloody diarrhea, dehydration, abdominal pain, and fever. Without treatment, dysentery can kill within days.

The outbreak starts with three prisoners developing symptoms. severe diarrhea, cramping, and fever. Within 48 hours, 12 more prisoners in the same barracks fall ill. Within a week, 52 prisoners across three barracks are infected. The camp medical staff, led by Captain Stevens, isolates sick prisoners and implements basic hygiene measures, hand washing, latrine disinfection, and separation of food preparation areas.

But these measures only slow the spread. They do not cure the infected. Stevens has limited medical supplies. Sulfa drugs, the primary antibiotics available in 1943, are in short supply and reserved for critical cases. Stevens has enough sulfa for maybe 10 patients. He cannot treat 52. Six prisoners die from dysentery in the first two weeks of the outbreak.

Stevens knows more will die if he cannot find a treatment solution. Ernst is one of the 52 infected prisoners. He developed symptoms 8 days into the outbreak. He experiences severe diarrhea 10 to 15 episodes per day and loses significant fluids. His weight drops from 160 lb to 140 lb in 5 days. Ernst feels weak, dizzy, and constantly thirsty.

He reports to the camp hospital and Stevens examines him. Stevens explains that dysentery is a bacterial infection of the intestines and there is no cure without antibiotics. Ernst must drink water to stay hydrated, eat bland foods if he can keep them down, and rest. If symptoms worsen, Erns should report back immediately. Stevens gives Ernst oral rehydration salts, a mixture of sugar and salt dissolved in water that helps replace lost fluids and electrolytes.

Ernst returns to his barracks and follows Steven’s instructions, but the dysentery does not improve. It gets worse. We are still at Camp Alva, two weeks into the dysentery outbreak, and Ernst is lying in his bunk thinking about his grandmother. Before the war, Ernst grew up on his grandmother’s dairy farm in the Bavarian countryside.

His grandmother raised cows, produced milk and cheese, and sold dairy products to local villages. Ernst worked on the farm from childhood, learning everything about dairy production. One memory stands out. When Ernst was 12 years old, several children in the village developed severe diarrhea after drinking contaminated well water.

The local doctor had no medicine to treat them. Ernst’s grandmother prepared a special mixture, fresh milk that had been allowed to sit for 24 hours until it soured slightly mixed with a small amount of sugar. She gave this mixture to the sick children, telling them to drink it slowly throughout the day. Within 2 days, the children’s diarrhea stopped.

Ernst asked his grandmother how sour milk could cure diarrhea when everyone said milk made stomach problems worse. His grandmother explained that fresh milk could upset sick stomachs, but slightly fermented milk contained special bacteria that helped the intestines heal. Ernst remembers this story as he lies in his bunk suffering from dysentery.

The camp hospital has no antibiotics to give him. The rehydration salts only replace fluids. They do not cure the infection. Ernst wonders if his grandmother’s sour milk remedy could work for dysentery. The problem is Ernst has no access to fresh milk. The camp kitchen uses powdered milk, a dehydrated form of milk that can be stored for long periods without refrigeration.

Ernst has seen powdered milk used in cooking, but never tried to reconstitute it as drinking milk. He wonders if powdered milk could be fermented the same way his grandmother fermented fresh milk. Erns decides to try. He has nothing to lose. He is already dying slowly from dehydration and malnutrition caused by constant diarrhea.

Erns goes to the camp kitchen during the afternoon work detail. He asks one of the prisoner cooks, a man named Werner, if he can have some powdered milk. Wernern asks why. Ernst explains he wants to try making fermented milk to treat his dysentery. Wernern looks skeptical but gives Ernst a small tin containing about two cups of powdered milk.

Ernst takes the tin back to his barracks. He mixes two tablespoons of powdered milk with one cup of lukewarm water in his canteen. The mixture dissolves into a white liquid that looks like regular milk. Ernst lets the mixture sit in a warm corner of the barracks for 24 hours. The Oklahoma heat accelerates the fermentation process.

Bacteria present in the air and on the canteen surface begin breaking down the milk sugars. When Ernst checks the mixture the next day, it smells slightly sour and has thickened somewhat. It is not exactly like his grandmother’s soured milk, but it is close enough. Ernst drinks half the mixture slowly over the course of an hour.

We are now 24 hours after Ernst drank his first batch of fermented milk powder mixture and something unexpected is happening. Ernst’s diarrhea frequency has decreased. Instead of 10 to 15 episodes per day, he has only six. The consistency of his stool is less watery. The cramping pain in his abdomen has lessened. Ernst feels slightly stronger.

He makes another batch of the fermented milk mixture and drinks it throughout the second day. By the end of the second day, Ernst’s diarrhea has decreased to three episodes. By the end of the third day, his stool is almost solid. By the fifth day, Ernst’s dysentery symptoms have completely resolved.

He has gained back 5 lbs. His energy has returned. Ernst cannot believe it worked. His grandmother’s folk remedy, adapted with powdered milk instead of fresh milk, cured his dysentery. Other prisoners in the barracks notice Ernst’s recovery. One prisoner, a man named Heinrich, who is also suffering from dysentery, asks Ernst what he did.

Ernst shows him the fermented milk powder mixture and explains the process. Heinrich asks if Erns can make some for him. Ernst agrees. He prepares a batch and gives it to Heinrich. Over the next three days, Heinrich’s dysentery improves dramatically, following the same pattern as Ernst’s recovery. Word spreads through the barracks.

Within a week, 20 prisoners with dysentery are drinking Ernst’s fermented milk mixture. All 20 show improvement. The recovery rate is 100% among prisoners who try the mixture, but none of the camp medical staff know this is happening. Ernst and the other prisoners are treating themselves without official approval or supervision.

This continues until Captain Stevens makes a routine inspection of barracks 12 and discovers Erns distributing his mixture to sick prisoners. Stevens walks into the barracks and sees Ernst mixing powdered milk with water in a large pot. Several sick prisoners are lined up with cantens waiting for Erns to fill them. Stevens asks what is going on through the camp interpreter, Corporal David Klene.

Ernst explains his fermented milk treatment and claims it cured his dysentery and is curring 20 other prisoners. Stevens is shocked and angry. He says Ernst is practicing medicine without training or authorization. Stevens says giving milk to dysentery patients is medically dangerous. Milk can worsen diarrhea by introducing more material for bacteria to feed on.

Stevens orders Erns to stop the treatment immediately. Ernst refuses. He says 20 prisoners are already improving. Six prisoners have died from dysentery in the camp hospital where they received official treatment. Zero prisoners have died using his mixture. Ernst asks Stevens which approach is actually working.

Let us know in the comments where you are watching this from. Are you in the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, or somewhere else. We would love to know who is keeping these stories alive. We are still at Camp Alva, and Stevens is facing a decision. He can shut down Ernst’s treatment and reassert medical authority, or he can investigate whether the treatment actually works.

Stevens chooses to investigate. He tells Erns to continue the treatment but to document every patient carefully. Name symptoms before treatment, dosage of mixture and symptoms after treatment. Stevens will monitor the patients and evaluate outcomes. If the treatment works, Stevens will allow it to continue. If patients worsen, Stevens will shut it down and provide hospital care to whoever needs it.

Ernst agrees to these terms. Over the next seven days, Stevens personally examines all 20 prisoners who are using Ernst’s fermented milk treatment. He checks their vital signs, asks about symptom changes, and observes their physical condition. The results are undeniable. All 20 prisoners show significant improvement, diarrhea frequency decreases, stool consistency normalizes, weight stabilizes or increases, energy levels improve.

None of the 20 develop complications. Stevens cannot explain it medically, but the evidence is clear. Ernst’s insane milk powder hack is working. Stevens expands the treatment to all remaining dysentery patients at Camp Alva. Over the next 3 weeks, 52 prisoners in total use the fermented milk mixture.

52 prisoners recover. Zero deaths occur among prisoners who use the mixture. The dysentery outbreak, which killed six prisoners before Ernst’s intervention, ends completely. Stevens asks Erns to explain exactly how he prepares the mixture. Erns describes the process through Klein. Two tablespoons of powdered milk mixed with one cup of lukewarm water.

Let the mixture sit in a warm place for 24 hours to allow fermentation. Drink one cup of the mixture three times daily with meals. continue for 5 days or until symptoms resolve. Stevens asks if the fermentation step is essential. Ernst says yes based on what his grandmother taught him. Fresh milk makes diarrhea worse because it is difficult to digest.

Fermented milk is easier to digest and contains bacteria that help restore healthy intestinal function. Stevens does not fully understand the mechanism, but he respects the empirical results. Ernst’s grandmother, a dairy farmer with no medical training, understood something about treating intestinal disease that 1943 medical science had not yet codified.

If you are enjoying this story and want more untold accounts from World War II prisoners of war, make sure to subscribe to the channel. We are bringing you stories that most history books never covered. We are now one month after Ernst introduced his treatment. But let us pause to understand the science behind why it worked.

Ernst’s fermented milk mixture is essentially a primitive form of probiotic therapy. When milk is left at warm temperature for 24 hours, naturally occurring lactic acid bacteria begin fermenting the milk sugars. These bacteria include species like lactobacillus and bifidabacterium. These bacteria produce lactic acid which lowers the pH of the mixture and creates an acidic environment.

This acidic environment inhibits the growth of harmful bacteria that cause dysentery including shagella and certain strains of eschericia. Additionally, the beneficial bacteria in fermented milk compete with harmful bacteria for resources and space in the intestinal tract. When dysentery patients drink fermented milk, they introduce billions of beneficial bacteria into their digestive systems.

These beneficial bacteria colonize the intestines, crowding out the pathogenic bacteria. The beneficial bacteria also produce compounds that strengthen the intestinal barrier and reduce inflammation. This is why Ernst’s treatment worked. Even though 1943 medical science considered it insane, the medical establishment knew that fresh milk could worsen diarrhea in some people because lactose, the sugar in milk, can be difficult to digest during intestinal infections.

But they did not yet understand that fermented milk with its reduced lactose content and high concentration of beneficial bacteria could actually treat infections. The concept of probiotics and the role of gut bacteria in health was not well understood in the 1940s. It would not be until the 1950s and 1960s that researchers began systematically studying the therapeutic effects of fermented dairy products.

By the 1980s, probiotic therapy was recognized as a legitimate medical approach for treating various intestinal conditions. Ernst, working from his grandmother’s traditional knowledge, was decades ahead of medical science. His insane milk powder hack was actually sophisticated microbiological therapy delivered through folk wisdom.

The 52 prisoners who recovered from dysentery at camp Alva were among the first documented cases of probiotic therapy for dysentery in a controlled setting though no one recognized it as such at the time. Let us examine the larger context of dysentery in prisoner of war camps during World War II. Dysentery was one of the most common and deadly diseases in camps worldwide.

Medical records indicate that 5 to 10% of prisoners in camps with poor sanitation experienced dysentery at some point during captivity. Mortality rates for untreated dysentery ranged from 10 to 30% depending on the severity of infection and the health status of patients. Malnourished prisoners were particularly vulnerable.

Dysentery killed through dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Patients lost massive amounts of fluid through diarrhea, sometimes several liters per day. Without intravenous fluids or effective antibiotics, many patients simply could not rehydrate fast enough to survive. At Camp Alva, the dysentery outbreak infected 58 prisoners total.

Six died before Ernst introduced his fermented milk treatment. That is a mortality rate of approximately 10% consistent with historical averages. But among the 52 prisoners who used Ernst’s treatment, the mortality rate was 0%. This represents a dramatic intervention effect. If the outbreak had continued without Ernst’s treatment and followed typical mortality patterns, an additional 5 to eight prisoners would likely have died.

Ernst’s grandmother’s remedy transmitted through Ernst to 52 sick prisoners prevented multiple deaths. The economic and human cost of those prevented deaths is immeasurable. Each prisoner who survived went on to live additional decades. Ernst’s intervention literally saved lifetimes. The broader significance of Ernst’s treatment extends beyond Camp Alva.

Stevens documented the intervention in his medical notes and submitted a report to the regional army medical command. The report described the fermented milk treatment, the outcomes, and Steven’s recommendation that the method be considered for future dysentery outbreaks in resource limited settings. Several other camps facing dysentery outbreaks requested details about the treatment.

It is unclear how widely the method was adopted, but Steven’s report ensured that Ernst’s grandmother’s folk remedy entered the official medical record. This documentation helped preserve knowledge that might otherwise have been lost or dismissed as prisoner superstition. The insane milk powder hack became a legitimate medical intervention documented and validated by military physicians.

We returned to camp Alva 2 months after the dysentery outbreak ended and Ern’s status in the camp has changed dramatically. He is known among prisoners as the man who stopped the dysentery. Other prisoners treat him with respect and gratitude. Some prisoners who recovered using his treatment give Ernst small gifts, handmade items, extra food portions, help with work assignments.

Ernst is uncomfortable with the attention. He insists he did nothing special, just remembered what his grandmother taught him. But the prisoners understand that 52 men are alive because Ernst acted when the camp hospital had no solutions. That is not nothing. That is everything. Stevens relationship with Ernst also evolves.

Initially, Stevens was angry that Ernst practiced medicine without authorization. But after seeing the results, Stevens respects Ernst’s empirical approach and willingness to challenge medical orthodoxy. Stevens asks Ernst if he knows other folk remedies that might be useful in the camp. Ernst describes several treatments his grandmother used.

Willow bark tea for pain and fever, chamomile tea for stomach upset, honey on burns and wounds. Stevens researches each remedy and finds scientific support for some of them. Stevens begins to see traditional knowledge as a valuable supplement to modern medicine, especially in situations where modern resources are unavailable.

This perspective shift is significant. A military doctor trained in modern medical science is learning from a 19-year-old prisoner with no formal education based on knowledge passed down from a dairy farmer. However, not everyone at Camp Alva celebrates Ern’s success. The camp commander, Colonel Richard Patterson, is concerned about the precedent.

If prisoners believe they can treat themselves without medical supervision, chaos could result. Patterson worries about prisoners experimenting with untested remedies and making themselves sicker. He tells Stevens that Ernst’s treatment worked this time, but it could easily have gone wrong. Stevens argues that Ernst’s treatment was validated through careful observation and documentation.

It was not reckless experimentation. Patterson remains skeptical. He issues a directive. Prisoners are not permitted to practice medicine or distribute treatments without explicit approval from camp medical staff. Ernst’s treatment is authorized retroactively, but future interventions must go through proper channels.

Ernst accepts this restriction. He never intended to become a camp healer. He just wanted to stop dying from dysentery. We are now in May 1945 and the war in Europe is over. Germany has surrendered unconditionally. Ernst is still at Camp Alva working on farm labor details and waiting for repatriation. The dysentery outbreak that threatened his life and the lives of 51 other prisoners is a distant memory.

Ernst is healthy, weighing 165 lbs, and looking forward to going home. He has received letters from his grandmother through the Red Cross confirming she survived the war. The dairy farm is still operating, though with fewer cows than before. Ernst writes back telling his grandmother that her soured milk remedy saved 52 men in an American prison camp.

His grandmother replies saying she is proud he remembered her lessons and used them to help others. Knowledge that works should always be shared. She writes that is how wisdom survives across generations. We are now in October 1945 and Ernst is approved for repatriation. He boards a transport ship with 1,300 other German prisoners returning to Europe.

The voyage takes two weeks. Ernst spends time thinking about his experience at Camp Alva, the dysentery outbreak, the decision to try his grandmother’s remedy, Steven’s initial anger and eventual acceptance, the 52 prisoners who recovered. Ernst wonders if anyone will remember what happened or if it will fade into the forgotten chaos of war.

When the ship docks in Braymond, Ernst goes through repatriation processing. He travels by train to Bavaria and finds his grandmother’s farm. His grandmother is 82 years old, thinner and frailer than Ernst remembers, but alive and sharp. Ernst tells her the full story of the dysentery outbreak and the fermented milk treatment.

His grandmother nods and says, “Soured milk has been used to treat stomach sickness for hundreds of years. Modern doctors forgot the old ways, but the old ways still work.” Ernst spends the next several years working on his grandmother’s dairy farm, helping her rebuild the operation after the war. When his grandmother dies in 1950, Ernst inherits the farm.

He runs it for 40 years, producing milk, cheese, and butter for local markets. Ernst marries in 1952 and has four children. He tells them stories about the war, including the story of the dysentery outbreak and the fermented milk treatment. His children ask if he ever contacted Captain Stevens to find out if the treatment was used elsewhere.

Ernst says no. He never followed up. The war ended and everyone moved on. But Ernst wonders occasionally whether his grandmother’s remedy saved other lives beyond Camp Alva. In 1987, Ernst receives an unexpected letter from the United States. It is from Stevens, now retired and living in California. Stevens found Ernst’s address through Army records and wanted to reconnect.

Stevens writes that he often thought about the dysentery outbreak and Ernst’s intervention. Stevens says he researched probiotic therapy after the war and realized Ernst’s treatment was scientifically valid decades before the medical community fully understood probiotics. Stevens thanks Ernst for teaching him to respect traditional knowledge and empirical results even when they contradict medical training.

Ernst writes back saying he was just a scared prisoner trying not to die. Stevens says that is how most breakthroughs happen. Desperate people trying unconventional solutions when conventional approaches fail. What does Ern’s story tell us about World War II prisoner of war camps and the intersection of traditional knowledge and modern medicine? On one level, it is a story about resourcefulness in crisis.

Ernst faced a deadly disease with no access to antibiotics or advanced medical care. Instead of accepting death, he remembered his grandmother’s folk remedy and adapted it to available resources. The insane milk powder hack was insane only to people who did not understand the science behind fermentation and probiotics.

To Ernst’s grandmother, who had seen soured milk cure intestinal illness many times, it was practical wisdom. Ernst bridged the gap between folk knowledge and medical application, saving 52 lives in the process. On another level, Ernst’s story is about the limits and strengths of formal medical training.

Stevens was a competent military doctor with years of experience. But when faced with a dysentery outbreak and no antibiotics, Stevens training offered no solutions. Ernst, with no medical training, but with practical knowledge from his grandmother, found a solution that worked. Stevens deserves credit for being open-minded enough to investigate Ernst’s treatment instead of shutting it down immediately.

Many doctors would have dismissed it as prisoner superstition and prohibited its use. Stevens chose evidence over ego. He observed outcomes, documented results, and validated Ernst’s approach when the data supported it. This intellectual humility allowed effective treatment to reach 52 prisoners who otherwise might have died.

The insane milk powder hack that shocked everyone at Camp Alva was not insane at all. It was probiotic therapy delivered through fermented dairy based on centuries of empirical observation. Ernst’s grandmother understood that beneficial bacteria could outco compete harmful bacteria in the gut. Modern medicine eventually reached the same conclusion through laboratory research and clinical trials.

But Ernst’s grandmother knew it first and Ernst remembered it when lives depended on that knowledge. The 52 prisoners who recovered from dysentery at Camp Alva survived because a 19-year-old prisoner valued his grandmother’s wisdom more than medical orthodoxy. Sometimes the insane thing is the most rational choice.

Sometimes survival depends on remembering what grandmothers taught