Normandy, 1944. A German Panther commander scans the horizon through his cupella. Open ground ahead, maybe 3,000 meters to the next treeine. No enemy visible, no muzzle flashes, no sound of artillery. He orders his driver forward. 30 seconds later, bullets begin falling at steep angles. Plunging fire that punishes anyone who exposes themselves.

Infantry caught in the open go down. The commander buttons up. Vision now limited to narrow periscopes. The advance slowed to a crawl. He never sees the gun that is harassing him. It is 2 mi behind the British lines, crewed by men who cannot see him either. This was the Vicar’s 303 medium machine gun, and the British used it in ways no other army understood.

Every nation in the Second World War fielded machine guns. The Germans had their MG42, a weapon so fast it sounded like tearing canvas. The Americans had their Browning reliable and robust, but no one else did it as routinely at battalion scale with artillery style planning. The British developed the mathematics, the training, and the doctrine to drop sustained automatic fire onto targets 4,500 yd away.

Targets the gunners could not see using principles borrowed from howitzer crews rather than riflemen. The problem was simple. Infantry advancing across open ground died. Tanks with open hatches were vulnerable. Commanders who needed to see the battlefield expose themselves the moment they raised their heads. Direct fire machine guns could suppress a position, but the enemy knew where that fire originated.

They could return fire. They could call in mortars. They could maneuver around the position. The machine gun announced itself with every burst. But what if fire could arrive without warning? What if bullets fell from empty sky onto a position that seemed safe from observation? What if a tank commander learned that no open ground was safe? That even 2 mi from the nearest visible enemy, his crew remained under threat.

The British solved this with the Vicers, a weapon that looked unfashionable by 1939. Water cooled when everyone else had moved to air cooling. Beltfed when box magazines offered faster reloading, heavy, requiring a 40lb tripod when the trend favored lightweight bipods for mobile warfare. The gun itself weighed 30 lb empty, 40 with water in the jacket.

Add the tripod and ammunition and a Vicar’s team carried over 90 before they fired a single round. German tacticians looked at this and saw yesterday’s technology. They were wrong. The Vicers fired the standard British 303 cartridge at a cyclic rate between 450 and 600 rounds per minute with a muzzle velocity of 2440 ft pers.

Those specifications matched or fell below German and American equivalents. The difference was what happened after the first 600 rounds. Aircooled guns overheat. Under sustained fire, MG42 crews had to change barrels frequently, often after a few hundred rounds of rapid bursts. Crews carried spare barrels and asbestous gloves for quick swaps, but those seconds created vulnerability.

More critically, German doctrine treated the machine gun as a maneuver weapon. High rate of fire for psychological suppression, then advance. The gun supported the squad. It did not operate as independent artillery. The Vicar’s water jacket held 7 and 12 Imperial pints. Water began boiling after approximately 600 rounds of continuous fire, but a flexible hose captured the steam and fed it to a condensing can.

This reclaimed the water, letting the gun run far longer than air cooled weapons if the crew managed heat, water, and barrels properly. With hourly barrel changes and adequate water supply, a Vicas could sustain 10,000 rounds per hour. Not for minutes, for hours, for entire battles.

Postwar endurance trials famously ran Vicar’s guns into the millions of rounds with minimal loss of function. Something air cooled guns could not match. This reliability enabled something no other army attempted at scale, indirect fire. British doctrine treated machine gun platoon as precision artillery batteries.

The MarkV tripod incorporated a dial site that allowed crews to calculate elevation and traverse without seeing the target. Range tables published in 50-yard increments provided tangent angles, wind corrections, time of flight, and beaten zone dimensions out to 4,500 yd. When firing later boat tailed ammunition, gunners learned trajectory mathematics.

They calculated adjustments for barometric pressure, temperature, and angle of sight. They used small repeatable tap corrections on the traversing gear to walk bursts across a target area. They were not aiming at men. They were aiming at grid squares. The beaten zone, that elliptical pattern where a burst strikes ground, change shape with range.

Close-range fire produced a narrow, elongated pattern because bullets traveled on flat trajectories. Medium-range fire created shorter, wider patterns as the angle of descent steepened. Beyond 2,000 yd, the pattern lengthened again as variations in muzzle velocity spread the rounds across a larger area.

Effective indirect fire required minimum four guns with overlapping beaten zones to ensure continuous coverage of the target area. Now, before we see how this performed in combat, if you are enjoying this deep dive into British engineering, consider subscribing. It costs nothing, takes a second, and helps the channel grow. Right back to the vicers.

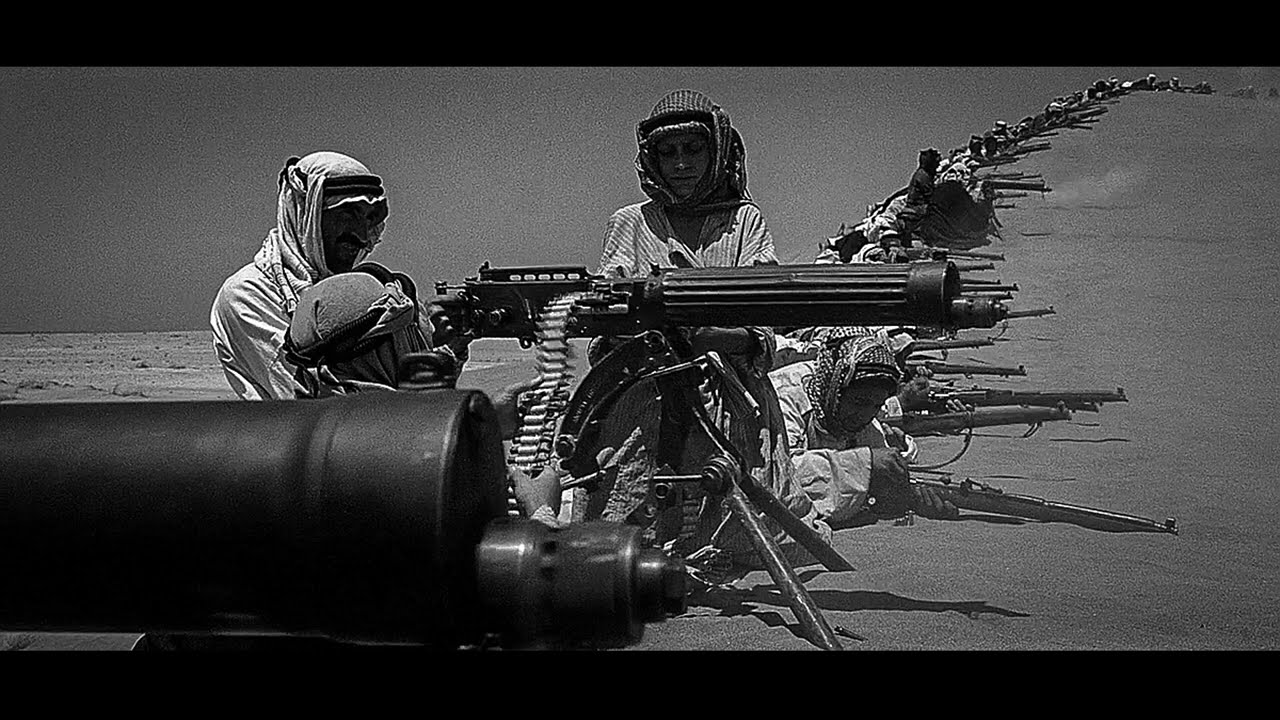

British forces organized their Vicar’s guns into dedicated machine gun battalions at divisional level rather than distributing them to infantry companies. The Middle Sex Regiment, the Manchester Regiment, the Cheshire Regiment, and the Royal North umberland fuseliers all converted battalions to this role between 1936 and 1937.

Each battalion fielded between 36 and 48 Vicar’s guns, organized into companies of 12, often with attached heavy mortars. In late war organizations, this centralization meant machine gun fire was planned at brigade level, coordinated with artillery programs, and delivered as part of integrated fire plans. Rather than reactive suppression, the guns traveled in universal carriers, giving them mobility to reach firing positions quickly, then delivered sustained indirect barges that could last hours.

Imperial War Museum records confirm Vicar’s teams operating in every major British campaign. The King’s Own Regiment at Tbrook in November 1941. The second New Zealand division at Monte Casino using rangefinders for indirect fire against German positions in the Monastery Heights. The second Cheshure Regiment supporting 50th division at Ole Bag in June 1944.

First commando brigade at the Rin crossing in March 1945. By 1945, British forces had refined combined arms tactics to devastating effect. Operation Veritable in February 1945, the push to the Rine employed what planners called the Pepper Pot method. This coordinated machine gun battalions with 4.2 2-in mortars, anti-aircraft guns in ground rolls, tanks, and conventional artillery into integrated barages.

850 pepper pot barrels fired alongside 1,050 artillery pieces. The vicers provided sustained intermediate fire, filling the gap between mortar shells and artillery rounds with continuous streams of plunging bullets that denied movement across entire sectors. The most detailed combat account comes from Rex King Clark’s diary forward from Kahima documenting the second battalion Manchester regiment in Burma.

The battalion served as the divisional machine gun battalion for second British division during the critical battles at Kahima and Impal between April and June 1944. King Clark was ordered to compile accounts of Vicar’s effectiveness from the division’s infantry regiments, creating primary source material for how the weapon actually performed against Japanese positions.

At outpost Snipe during Alamine in October 1942, Vicar’s guns of the second battalion rifle brigade engaged German tank crews fleeing destroyed vehicles. According to regimental accounts, the guns cut down tankers as they ran desperately for safety across open ground. The men operating those guns could see their targets, but the same weapons positioned further back and firing on calculated bearings could have achieved similar results against crews who believed themselves safe.

German doctrine never developed equivalent capability despite having the theoretical means. The MG34 and MG42 mounted on the Lafet 42 tripod with the MGZ 3440 telescopic site could deliver fire to 3,500 m. The unique Tif and Foyer automat mechanism even automated beaten zone sweeping. But German doctrine focused on direct fire support for maneuver, not planned sustained indirect bargages.

They built their tactics around the machine gun as squad weapon, not divisional artillery. Every German infantry squad carried one MG, giving German units higher automatic firepower at close quarters, but no capability for the sustained longrange barges that British doctrine demanded. The American M1917 water cooled Browning offered comparable sustained fire performance.

In testing, 1 M1917 fired 21,000 rounds in a 48minute continuous burst. American heavy weapons companies did practice indirect fire, but the lighter air cooled 1919 4, which became the standard lacked a quick change barrel, so sustained rates had to be kept conservative. American doctrine moved toward volume of fire and mobility rather than sustained precision where British battalions concentrated their vicers for coordinated divisional shoots.

American units dispersed their machine guns for direct support, sacrificing the artillery effect for immediate responsiveness. The Vicers remained in British frontline service until the Radfan campaign in Aden in the early 1960s, finally retiring in 1968 after more than half a century of continuous service, the longest of any British army weapon system.

India maintained Vicers into the 1980s and beyond. Confirmed reports place Vicar’s guns in the Syrian Civil War in the 21st century, over 100red years after the design’s adoption. One legend deserves mention, though it has been academically debunked. The famous claim that 10 guns of the 100th machine gun company fired 1 million rounds over 12 hours at high wood on August 24th, 1916, makes for dramatic storytelling.

Peer-reviewed research by Dr. Rich Willis and Richard Fischer. Published in First World War Studies in 2019, analyzed war diaries and technical capabilities, the actual figure was approximately 99,500 rounds from six guns. still remarkable for 12 hours of sustained fire, but the million round claim was postwar embellishment.

What remains verified is this. The British developed a tactical system that turned a 50-year-old weapon into something unprecedented. While German engineers designed the fastest firing infantry weapon of the war, British doctrine transformed a slower, heavier, more primitive design into divisional artillery that could reach 2 and 1/2 miles and sustain fire for hours.

German tank commanders learned to fear open ground, not because they could see the threat, but because they could not. Somewhere beyond the horizon, behind hills they could not observe, vicers. Crews were calculating angles and checking wind tables. The bullets would arrive without warning, falling from above, striking surfaces that direct fire could never reach.

That was British engineering. Not just building a superior weapon, but developing a superior way to use it. The Germans built the fastest machine gun. The Americans built the most mobile. The British built a system, a complete tactical doctrine that transformed an Edwwardian design into something their enemies never learned to counter.

Other armies could do indirect fire on paper. The British built a doctrine and an organization that made it routine.