December 9th, 1944. Camp Upton, Long Island, New York. The transport truck’s engine died with a metallic groan. 37 boys, aged 12 to 16, sat frozen in the cargo bed, their breath fogged in the bitter cold. None of them spoke. The tailgate dropped. >> All right. >> American soldiers in heavy wool coats gestured for them to dismount.

down here and form up by the barracks. >> The boys climbed down stiffly, their summer weight uniforms offering no protection against the December wind. They had been told nothing during the 3-day voyage across the Atlantic, only that they were being transferred to a detention facility, only that their war was over.

Then one boy saw it, a pendant catching the weak afternoon light. Six points, a star of David, hanging from the neck of Corporal David Rothstein, standing third in the line of guards. The boy’s face drained of color. He whispered something in German. The word spread like contagion through the group. Jude, Jew. In that moment, every propaganda film they’d ever watched came flooding back.

Every poster in every classroom, every speech by every youth leader. The enemy wasn’t just American. The enemy was here. And he wore a uniform. And he carried a rifle. and he was staring right at them. What happened next would shatter everything they’d been taught since they could first understand words. These were not ordinary prisoners of war.

They were Hitler Yugand, Hitler Youth, captured during the final desperate months of Germany’s collapse. Some had been taken in France during the autumn retreat, others in Belgium during the Arden’s preparations. The youngest had been pulled from anti-aircraft batteries defending Hamburg and Cologne. Boys trained to operate flack guns.

Boys who’d never shaved. Boys who believed the furer’s promises with the absolute faith that only children possess. The American military didn’t know what to do with them. Geneva Convention guidelines covered soldiers, but these weren’t soldiers in any traditional sense. They were minors, indoctrinated minors.

Some arrived still wearing short pants and knee socks beneath their Vermach tunics. Their identification papers listed birth dates that made seasoned sergeants shake their heads. 1930 1931 1932. Children born into a world already twisting toward madness. Camp Upton had been established during the First World War, decommissioned, then hastily reopened in 1940.

By December 1944, it housed over 400 German PS. Most were vermached regulars, exhausted, disillusioned men who’d survived Normandy or Italy. They played cards. They read letters. They waited for the war to end. They caused no trouble. The Hitler youth arrivals changed everything. They sang Nazi anthems during morning formation.

They refused to work alongside traitors, their term for regular army prisoners who’d accepted defeat. They carved swastikas into wooden bunks. They stood at rigid attention whenever an officer passed, even American officers, because discipline was identity, and identity was all they had left. David Rothstein had been watching these dynamics for weeks.

A 23-year-old from Brooklyn, he’d volunteered in 1942 after his cousin died at Cassine Pass. he’d expected to fight. Instead, the army had assigned him to the prisoner of war processing command based on his fluency in Yiddish and German. His grandmother had spoken both. She’d fled Kov in 1920. She’d seen the early signs.

She’d saved her family by leaving before the borders closed. Now he stood guard over the children of the regime that had murdered the relatives she’d left behind. The irony wasn’t lost on him. Neither was the rage, neither was the pity. He felt all three simultaneously, constantly, exhaustingly. He kept the Star of David visible because his commanding officer had advised discretion, and David Rothstein was done being discreet.

If these boys were going to learn anything, they’d learn it honestly. The new arrivals filed into barracks 7. An older prisoner, a former artillery sergeant named Mueller, tried to speak to them in German. They ignored him. Collaboration, even conversational, was betrayal. They arranged their thin mattresses in perfect rows.

They stood beside their bunks until ordered to sit. 17 years old and already harder than stone. 14 years old and already unreachable. Night fell. Temperature dropped. The barracks were heated, but barely. Someone had miscalculated coal rations. The regular prisoners wrapped themselves in extra blankets, doubled up for warmth.

The Hitler youth suffered in silence. Complaining was weakness. Shivering was weakness. Everything was a test of will, and will was the only currency they had. David Rothstein walked his patrol route. Guard towers every 50 yards, flood lights every 20. The fence wasn’t electrified. No need given the alternatives escapees faced. Long Island in December.

No papers, no contacts, no language, no money. Escape was theoretically possible, but practically suicidal. The prisoners knew this. Most accepted it. The boys didn’t accept anything. They simply endured. Around midnight, the first snow began. Light flurries at first, then heavier. By Oro 200 hours, visibility had dropped to 30 ft.

By Oro 400, the wind was howling through gaps in the barracks walls. The heating system, already inadequate, struggled and failed. Someone reported the coal bin was empty. Refueling wouldn’t happen until dawn. Morning roll call was mandatory. 6:00 a.m. regardless of weather. Security protocol demanded headcount verification before dawn.

David Rothstein pulled his coat tighter as he walked toward barracks 7. His breath crystallized instantly. Snow had drifted 3 ft against the northern wall. Inside, the boys were already awake, already dressed, already standing at attention beside their bunks, exactly as regulations demanded, even though no American regulation had ever demanded this. The door opened.

Cold air poured in. Sergeant Morrison called out in broken German, “Rouse, formation, Schnel.” Outside formation quickly, the boys filed out in perfect order. No coats, no gloves, no hats. Only the summer uniforms they’d been captured in. The uniforms Germany had issued when it still believed victories were possible.

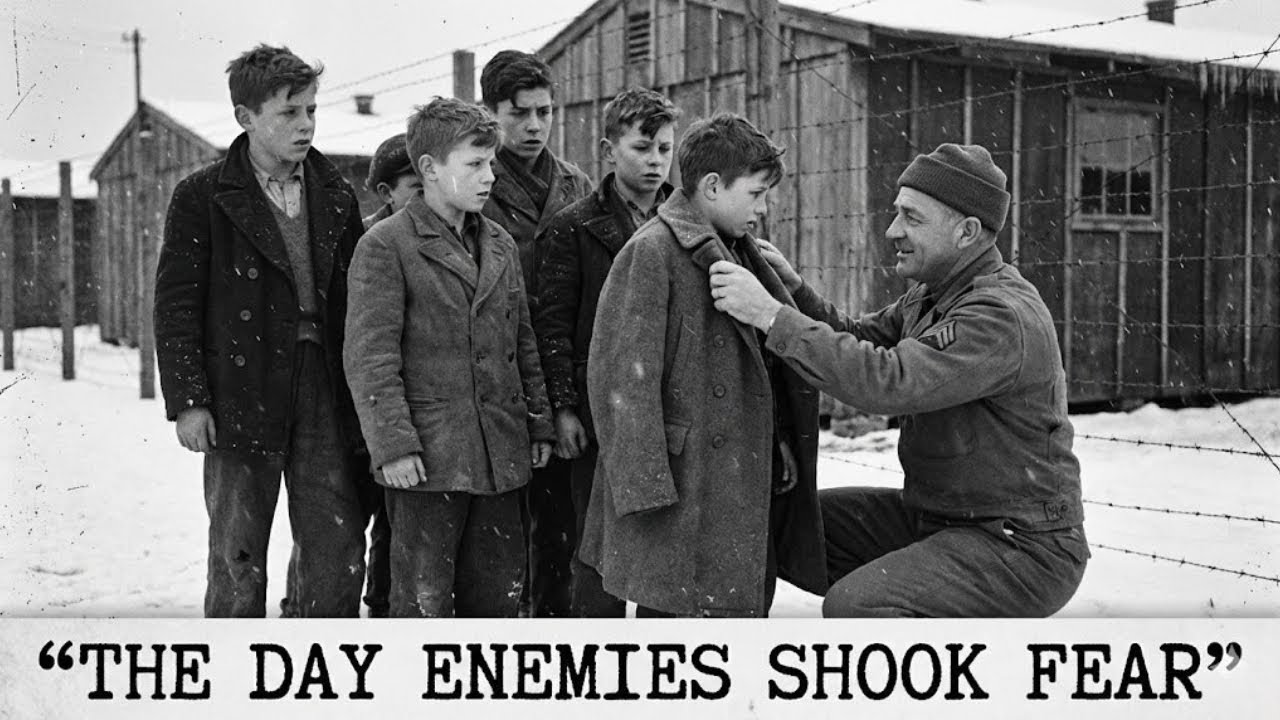

When it still believed boys would march through sunshine and glory, not blizzards and captivity. They formed ranks in the snow, five rows, seven boys per row, two shorter rows at the end. The wind cut through them like razors. David watched from his position near the fence line. He saw them shaking, saw them locking knees to keep from collapsing, saw them staring straight ahead with eyes that refused to acknowledge cold or fear or doubt.

One boy in the third row was smaller than the others, maybe 13, maybe younger. His tunic hung loose on his frame. His face had the hollow look of chronic hunger. His hands, clenched at his sides, were blue, not pale, blue. Before we begin this journey through one of war’s most unexpected encounters, take a moment to like this video and subscribe to our channel.

Share in the comments where you’re watching from. Whether you’re in Berlin or Boston, we’re honored to have you here. These stories matter because they remind us that humanity can survive even the darkest indoctrination. Now, let’s continue. Sergeant Morrison began the count. He walked down each row, pointing, verifying numbers against his roster. The process took 4 minutes.

4 minutes in sub-zero wind. 4 minutes standing motionless. The small boy swayed just slightly, enough that David noticed, not enough that Morrison saw. Second row, third row. Morrison was halfway through when the boy’s knees buckled. He caught himself, straightened, stood rigid again. David took a step forward, then stopped.

Regulations prohibited fraternization with prisoners outside designated work assignments. Regulations prohibited physical contact except in cases of medical emergency. This wasn’t quite an emergency. Not yet. Fourth row. Fifth row. The boy swayed again. This time he didn’t catch himself. He went down face first into the snow.

Morrison stopped counting. Silence. The other prisoners stared straight ahead. Protocol demanded they ignore weakness. Acknowledge it was to share it. Sharing it was contagion. Morrison called for a medic. Standard procedure. The medic would arrive in three, maybe four minutes. David Rothstein looked at the boy lying in the snow.

Looked at the star of David hanging against his chest. Looked at the other prisoners still standing at attention, still pretending their comrade didn’t exist. He walked forward past Morrison, past the front row, directly to the fallen child. He knelt. The boy was conscious but unresponsive. Eyes open, breathing shallow, shivering so violently his jaw couldn’t close.

David didn’t ask permission, didn’t check regulations, didn’t think about doctrine or protocol or the Reich propaganda these boys had been fed since kindergarten. He unbuttoned his coat. Heavy wool, army issue, lined with cotton flannel. standard cold weather gear for guards in northern winters. He pulled it off.

The cold hit him immediately. He wrapped the coat around the boy’s shoulders, lifted him slightly, pulled the collar tight around the narrow throat. The boy’s eyes focused, fixed on David’s face, then dropped to the star of David, now inches away, swinging slightly in the wind, catching the pale pre-dawn light. Six points. Gold medal.

The symbol that every poster, every film, every teacher, every leader had taught him to hate. The symbol of corruption, of conspiracy, of everything wrong with the world. The symbol of monsters. The symbol on the coat that was keeping him from freezing to death. The boy stared. David met his eyes, said nothing.

There was nothing to say that the moment wasn’t already saying louder. around them. The other prisoners began to move. Just small movements, heads turning, shoulders relaxing. The formation broke, not dramatically, subtly, like ice cracking in slow motion. Someone coughed. Someone else shifted weight. The spell of absolute discipline fractured.

The medic arrived, took the boy from David’s arms, wrapped him in a standardisssue blanket, and walked him toward the infirmary. David stood, brushed snow from his knees. His undershirt was soaked with sweat despite the cold. He realized his hands were shaking, not from temperature, from the sudden overwhelming weight of what had just happened, or what hadn’t happened, or what should have happened, but didn’t.

Sergeant Morrison finished the count, dismissed the formation. The boys filed back into the barracks. David retrieved his coat from the infirmary an hour later. The boy was asleep under heated blankets. Mild hypothermia. He’d recover physically. The next morning, the same formation. 6:00 a.m. Same cold, same snow.

But this time, when the Hitler youth emerged from barracks 7, 17 of them wore makeshift coats, blankets tied with rope, burlap sacks with armholes cut. One boy had wrapped himself in a disassembled mattress cover. They looked ridiculous. They looked human. David Rothstein took his position by the fence.

The small boy from yesterday stood in the third row again. This time in a borrowed jacket three sizes too large. His eyes found Davids across the parade ground. No salute, no smile, just acknowledgement, just the faintest nod. Just the beginning of something that might eventually become understanding. The incident spread through the camp within days. Prisoners talked, guards talked.

Everyone had an opinion. Some thought David was soft, some thought he was strategic. Break their ideology, make them compliant. Some didn’t care either way. But the Hitler youth noticed, more importantly, they remembered over the following weeks, small changes emerged. A boy asked for medical attention without being ordered.

Another requested permission to write a letter home. A third sat next to a regular vermarked prisoner during meal distribution and didn’t immediately move. These weren’t conversions. These weren’t renunciations of belief. These were cracks, hairline fractures in the absolute certainty that propaganda had poured into their minds like concrete. The war ground on.

December became January. The Battle of the Bulge raged, then collapsed. Germany’s final offensive died in the snow. Just like the boy nearly had, news filtered into the camp slowly, unreliably. The prisoners heard rumors, victories, defeats, miracles, catastrophes. The Hitler youth stopped singing anthems, not because they’d lost faith, because faith had become complicated, because a Jewish soldier had given his coat to an enemy child, and no propaganda manual had prepared them for that possibility. David Rothstein never

discussed the incident. When other guards asked, he shrugged. When officers inquired, he cited regulations about preventing prisoner death. When his grandmother wrote asking about his service, he told her the weather was cold but manageable. He didn’t mention the boy, didn’t mention the coat, didn’t mention the look in those eyes when ideology crashed into reality.

Years later, decades later, a letter arrived at a Brooklyn address postmarked from Stoutgart written in careful formal English. It described a transport, a blizzard, a Jewish guard, a coat that saved a life. It asked if the recipient remembered. It offered no apology for beliefs once held because some things can’t be apologized for.

But it offered gratitude. Quiet, restrained, permanent gratitude, the kind that survives wars and decades and shame. David Rothstein kept the letter in his desk drawer. Never showed it to anyone. Never framed it. Never threw it away. Just kept it. evidence that a single act of mercy could outlive the machinery of hate.

That kindness offered without agenda in a moment of desperate cold could plant something small and persistent in soil that should have been barren forever. Camp Upton closed in 1946. The prisoners went home to a Germany that no longer existed. The guards returned to civilian life. The barracks were demolished, the fence posts removed, the land repurposed.

Nothing visible remains, but stories remain, passed down, retold, changed slightly with each telling until they become legend, until they stop being about specific people and become about principles, about choices, about the moment when someone decides the person in front of them is more important than the uniform, the faith, or the fear.

December 1944 was full of such moments. Most went unrecorded. A medic sharing rations with a wounded enemy. A chaplain praying with a dying soldier who spoke the wrong language. A pilot who didn’t fire on a crippled plane. Small mercies in a war designed to erase mercy entirely. None of them changed the outcome. Germany still lost.

Millions still died. Evil still carved its mark deep into history’s flesh. But for one 13-year-old boy shivering in the snow, the war ended differently than planned. Not with a bullet, not with a bomb, not with a surrender document, but with a coat and a pendant. And the sudden destabilizing realization that the monsters weren’t where he’d been told to look.

That hate was easy to teach, but hard to maintain when tested by simple human decency. that the man he’d been raised to fear had kept him from freezing. While the regime he’d been raised to love had sent him to die in a summer uniform, the boy never forgot. The guard never forgot. The story never forgot. Because some moments are too true to fade, too necessary, too perfectly illustrative of the line between what we’re taught and what we choose.

Between propaganda and reality, between the ideology that divides and the humanity that endures. The coat became a symbol. Not officially, not dramatically, just quietly, the way real symbols do. It hung in a Brooklyn closet for 40 years. then in a donation bin. Then on someone else’s shoulders, its history forgotten, its warmth recycled.

But for one winter night in 1944 on Long Island in a prisoner of war camp, it was everything. Proof that mercy doesn’t require agreement, that kindness doesn’t require shared belief, that sometimes the most powerful statement is the one made without words, just action, just presence, just one human being deciding another human being deserves to live.

The snow melted, spring came, the war ended. The boys went home to rubble and reconstruction. Most disappeared into ordinary lives. Some thrived, some struggled, some never recovered from what they’d seen and done and believed. But they all remembered the coat. All carried the image of that star of David swinging in the wind, providing warmth when it should have provided fear.

That’s the lesson that survived. Not complex, not philosophical, just undeniable. Evil teaches hate loudly and constantly. Goodness answers quietly once in the moment when it matters most. And sometimes, just sometimes, that’s enough. Enough to crack certainty. Enough to plant doubt. Enough to let a child realize the monsters were in Berlin, not New York.

Not wearing stars of David, but swastikas. Not offering coats, but demanding sacrifices. The blizzard passed. The boy survived. The guard continued his rounds. And somewhere in that frozen December morning, in the space between what was taught and what was true, a small piece of humanity proved stronger than an empire built on hate.

Not loudly, not dramatically, just completely. That’s what endures. Not the speeches, not the propaganda, not the flags or anthems or promises, but the coat and the boy and the Jewish corporal who decided a child’s life mattered more than history’s divisions. In the end, that decision outlasted the Reich by generations and will outlast all of us because kindness once given never fully disappears.

It just keeps moving forward. quiet, persistent, undeniable. The war taught a thousand lessons. Most were about destruction. This one was about something simpler, something older, something that no amount of indoctrination could completely erase. that we are first and always responsible for each other. Regardless of flags, regardless of beliefs, regardless of what we’ve been told to hate.

In the cold, we all need warmth. In the darkness, we all need light. And sometimes all it takes is one person willing to offer their coat.