Coast Guard Pilot Records a Mermaid Pulling a Human Body Into the Ocean

I’m Marcus Chen, 58, and in my basement, locked inside a fireproof safe beneath my workbench, sits a hard drive containing 47 seconds of footage that ended my Coast Guard career. I was a helicopter pilot for 14 years, flying over the California coast, searching for survivors, sometimes recovering bodies. But on October 12, 2001, I recorded something that changed everything.

For 23 years, I’ve kept this footage hidden. Two men in civilian clothes told me that discussing what I saw would violate federal law. They said it was an equipment malfunction. They said stress distorts perception. They said a lot of things easier to believe than what my camera recorded.

Last Tuesday, the Coast Guard announced new search operations in the same area where I flew that night. Three divers vanished during a night dive off Trinidad Head. Their boat was found anchored, gear still on deck, regulators and masks laid out for a second dive they never completed. The official statement mentioned strong currents and poor visibility. It didn’t mention this was the fourth cluster of disappearances in that area since 1971, all following the same pattern.

I still have the footage. I’ve watched it hundreds of times, trying to find some rational explanation. The thermal imaging shows a heat signature that doesn’t match any known marine animal. The optical recording shows movement that defies everything I learned about hydrodynamics. And the final three seconds show a face looking directly up at our aircraft before pulling a man’s body down into water too deep to measure.

I know how this sounds. I know what people think about Coast Guard pilots who claim to see things. But I was 35 years old that night, not some rookie. I had 2,000 flight hours. I knew the difference between a dolphin and a seal, between debris and a person, between camera artifacts and something real moving through the water.

My co-pilot saw it too. So did our flight engineer. All three of us watched it happen, and all three of us were told to forget what we saw.

I’m breaking my silence now because I don’t think those divers got disoriented. I don’t think they drowned from hypothermia. And I think the families searching for answers deserve to know that something in those waters has been taking people for decades. Something that moves with purpose. Something that looks almost human until you see it up close.

The Night That Changed Everything

The phone in our barracks rang at 2:47 a.m. Lieutenant Brady called for an immediate scramble. My co-pilot that night was Jake Morrison, a young but capable flyer. Our flight engineer was Danny Torres, a veteran who’d seen everything the Pacific could throw at a rescue crew.

We suited up quickly. Storm system moving south, gusting winds, cold water. The distress call came from a fishing vessel, the Pacific Dawn, 43 nautical miles northwest of Trinidad Head. The emergency beacon had activated, but no voice communication came through.

Our J-Hawk helicopter lifted off at 3:04 a.m. The flight out took half an hour. The darkness was absolute. No moon, heavy cloud cover, visibility low. Our instruments showed light rain. The ocean below was invisible except when our searchlight cut through the blackness.

At 3:35 a.m., Danny called out the first visual contact—a strobe light in the water. The Pacific Dawn was upside down, stern submerged, bow pointed up, debris scattered around. No life raft, no survivors visible.

Jake brought us down to 100 feet and started a search pattern. Danny readied the rescue basket. I worked the FLIR camera, searching for heat signatures. In cold water, a human body stays warm enough to register for maybe an hour.

The FLIR showed the warm signature of the engine, some smaller signatures that might have been fish or debris. Then, at the edge of our search radius, a clear human-shaped signature floating in the water.

Contact, I called. Heat signature, 200 yards out. Jake turned the aircraft. The signature wasn’t moving, just floating on the surface, arms spread. We had a survivor, or at least a body.

Jake held us steady above the target. I swung the searchlight around. That’s when I first saw something else on the FLIR display—another heat signature, smaller and moving fast, approaching the body from deeper water.

At first, I thought it was a seal. But the signature was wrong. Too warm for a fish, wrong shape for a seal, and coming up from directly below.

The searchlight hit the water at 3:41 a.m. The body was male, face down, wearing a commercial fishing vest. He floated, unresponsive.

Danny lowered the rescue basket. I kept the searchlight on the body, monitoring the FLIR. The secondary heat signature was still there, ascending, now maybe 40 feet below the surface. I could see it clearly—elongated, warmer than the water, cooler than the body above.

It moved with purpose, not the random motion of a fish or marine mammal.

“Danny, we’ve got something in the water below the victim,” I said. “Possible marine life, large animal approaching from depth.”

“Copy that,” Danny replied, calm. We’d dealt with curious sea lions before, but this felt different.

The basket was 30 feet from the water. Jake adjusted our position. The aircraft was stable. This should have been a straightforward recovery.

The secondary signature reached 15 feet below the surface. I could see it more clearly now, and the shape didn’t match anything I knew. Too streamlined for a seal, too large for a dolphin, wrong thermal profile for a shark.

I switched on the optical camera, zoomed in on the body. With our searchlight, the picture was clear enough to see details.

The basket touched down next to the body. Danny maneuvered it closer. That’s when the thing in the water reached the body.

I saw it first on the FLIR. The secondary signature merged with the human signature. Then I saw it on the optical camera—movement directly beneath the body. Something pale, breaking the surface.

Jake, do you see that? My voice stayed level, but my heart raced.

Danny’s voice came through. “I’ve got visual. There’s something circling the basket. Not a seal. Too large. Moving wrong.”

I zoomed tighter. Inside the circle of the searchlight, I saw her.

She circled the body once, moving clockwise, maybe five feet below the surface. The thermal signature showed a mammal. The optical camera showed pale skin, long dark hair, movement too fluid to be a corpse. Arms too long, hands with webbed fingers, legs fused or bound together, undulating in a vertical motion.

She stopped beneath the body, maybe eight feet down. The water clarity was poor, but our cameras penetrated the turbulence. I saw her looking up—not at the body, at us.

Her face was visible for three seconds in the searchlight. Human, but wrong. Eyes too large, set too far apart. Nose small, mouth wider than it should be. Skin pale gray-white, like something that never saw sunlight.

She raised one arm toward the body. The hand was webbed, fingers elongated, ending in claws or long nails.

Her hand wrapped around the victim’s ankle, gripping firmly.

“Danny, abort the rescue,” I said. Training overrode shock. “Pull the basket up. There’s someone in the water with the victim.”

“That’s not a person,” Danny said, voice tight.

Jake inhaled sharply. He was watching his own display. We were all seeing the same thing.

She pulled. The victim descended, life vest compressing as she pulled him down. She was strong, much stronger than her build suggested.

“Get the basket out of there,” Jake said. Danny reeled in the cable. The basket lifted from the water.

The victim was now ten feet beneath the surface, sinking faster. She had both hands on him, one on his ankle, one gripping his belt. She was pulling him down in smooth, powerful yanks.

His arms drifted upward, reaching for the surface. The back of his head was visible, dark hair plastered to the skull. Then he rotated and I saw his face—eyes closed, mouth open, skin waxy pale.

She looked up at us again, paused, treading water vertically, holding the body with one hand, staring into our searchlight. Her face filled my monitor, eyes reflecting greenish light, mouth open, teeth sharp, pointed.

We held eye contact for three seconds. No fear, no aggression, no emotion I could read. Just that steady, unblinking stare.

Then she looked down, adjusted her hold, and pulled him into a vertical embrace. Her legs wrapped around his waist, movement practiced. She held him against her chest the way you’d hold a child.

She began descending, swimming down, pulling the body with her into deeper water. Her thermal signature faded, her form disappeared into darkness.

The victim’s life vest broke free, popping to the surface, straps torn. The force had ripped it off his body.

Jake held the hover for another 30 seconds. None of us spoke. I kept the camera pointed at the spot where they disappeared, hoping for something that would make sense of what we’d witnessed.

The FLIR showed no heat signatures. She was gone. He was gone. The ocean was empty except for the torn life vest and debris.

Aftermath

We returned to base, debriefed in silence. Brady listened, took notes, called in two men in suits. They reviewed the footage, told us it was an equipment malfunction, a psychological error, debris in the water. They made us sign non-disclosure agreements, threatened federal charges if we spoke.

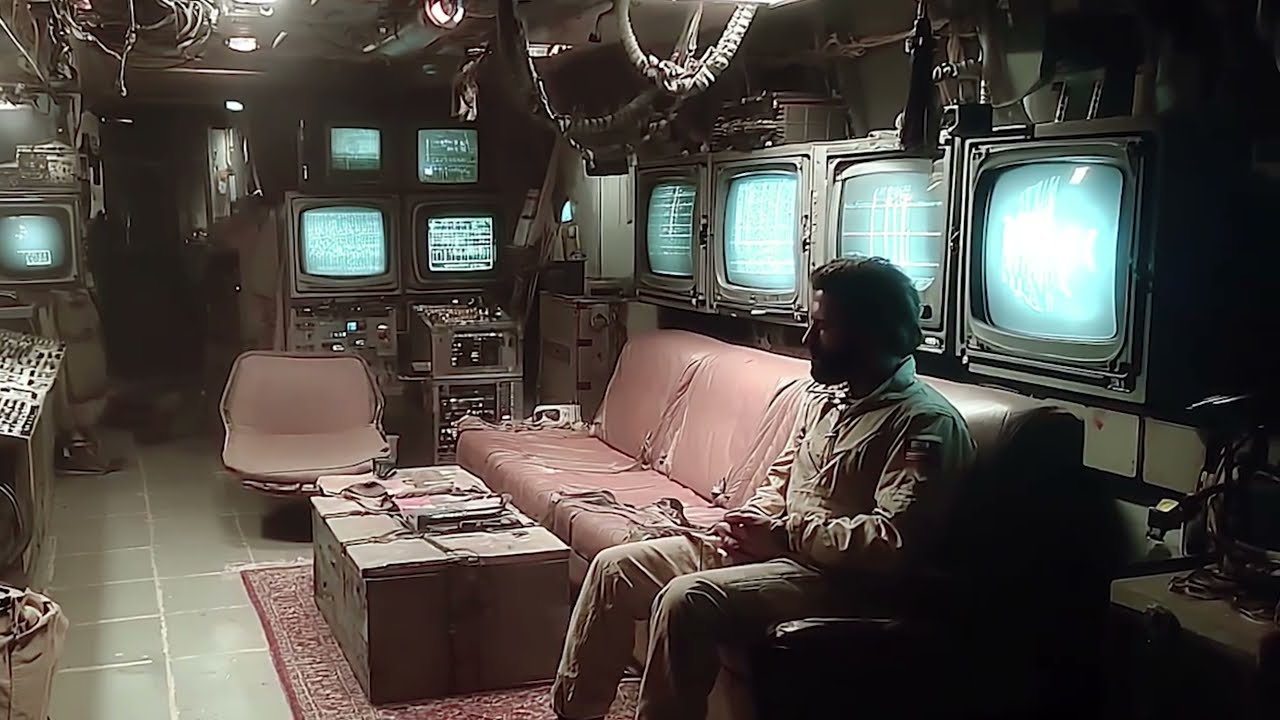

I kept a backup copy of the footage, hidden in my safe. I watched it, frame by frame, analyzing every detail—the way her hair moved, the way her eyes reflected light, the way her hand gripped the ankle, the strength in her arms.

I researched disappearances along the coast. I found clusters of incidents—boats found with gear intact, life vests torn, bodies missing. Official explanations always blamed weather, currents, hypothermia.

I found a dissertation by Dr. Sarah Winters, documenting unexplained predation events along the California coast. She’d submitted her findings to federal agencies in the 1970s. All had declined to fund further research. She left academia, her work buried.

I met other Coast Guard veterans who’d seen similar things. Their reports disappeared, their careers quietly redirected. The pattern was always the same—night operations, deep water, missing persons, official silence.

I built a database, tracking incidents, mapping clusters. The pattern was clear: deep water near rocky coasts, disappearances in cycles, most in cold months, most at night.

I shared the footage with three experts. A marine biologist told me it didn’t match any known species. A video forensics expert found no evidence of manipulation. A retired Coast Guard captain confirmed he’d seen something similar.

But I never went public. The risk was too high. The footage stayed in my safe, copies hidden, the truth buried.

The Burden of Knowledge

For 23 years, I’ve carried this secret. I haven’t been on a boat since that night. I haven’t gone swimming. I don’t walk the beach. I keep the footage locked away, the research notes stacked beside it.

Every time another disappearance is reported, I wonder how long the cover-up can last. How many more families will be told their loved ones drowned, swept away by currents, lost to the sea?

I don’t know what lives beneath those waters. I don’t know what it wants, or why it takes people. I only know what I saw, and what I recorded.

If you’re reading this, know that there are mysteries the ocean still keeps. Some secrets are locked away in safes and minds, waiting for the world to be ready to understand.

I hope, one day, someone will find the courage to tell the story in full. Until then, I keep the routine: the research, the silence, the memory of a face looking up from the deep.