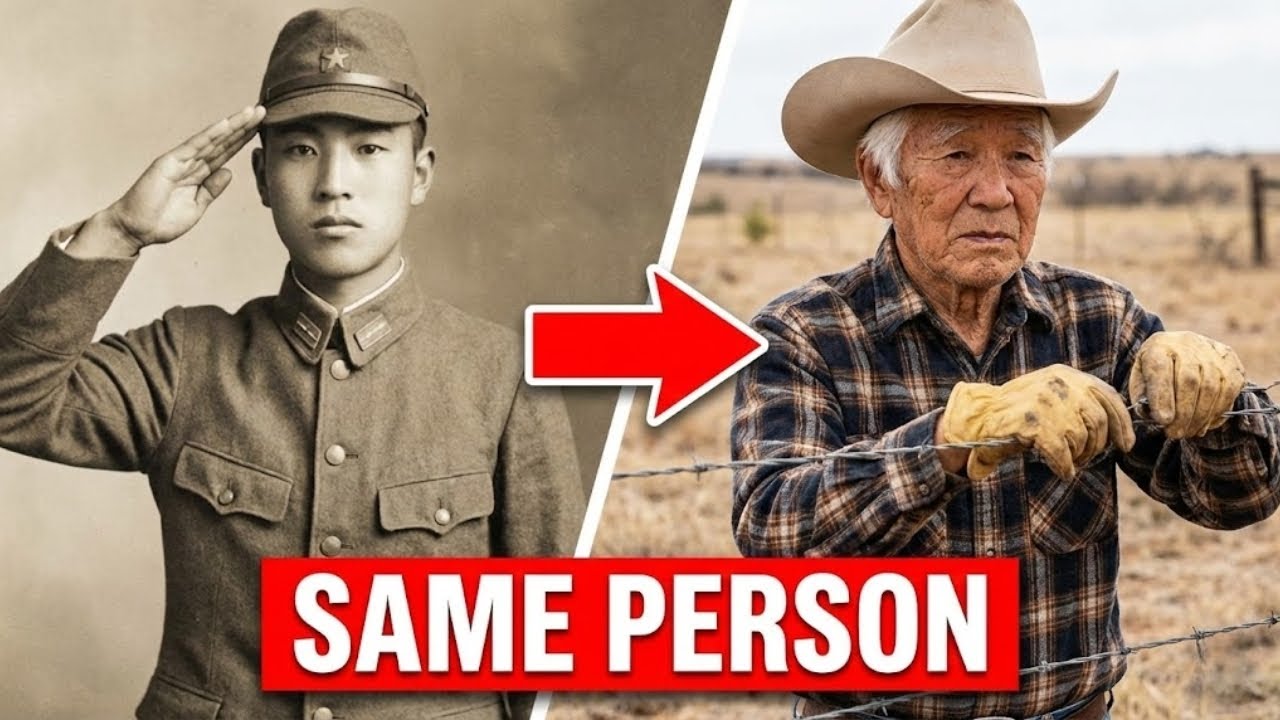

The Man Who Vanished Twice: The Breathtaking Secret Life of Hiroshi Tanaka, the Japanese POW Who Became a Texas Legend

History is typically a collection of loud moments—the thunder of artillery, the roar of political speeches, and the sharp lines of treaties signed in ink. But sometimes, the most profound stories are written in the margins, in the quiet spaces between the lines of official reports. In April 1943, at Camp Hood, Texas, a young Japanese soldier named Hiroshi Tanaka stepped into one of those margins and stayed there for nearly fifty years. He did not just escape a prisoner of war camp; he escaped his own history, shedding one identity like a worn-out skin to become someone else entirely in the rugged, sun-scorched hills of central Texas.

The Code of the Ghost

To understand Tanaka’s decision, one must understand the crushing weight of the world he left behind. In the Japanese military of the 1940s, the warrior code of Bushido left no room for the concept of a “prisoner of war.” To be captured was to be dead—to your family, to your country, and to your own honor. Tanaka had been a fisherman’s son from Hiroshima, conscripted and sent to the biblical cold of the Aleutian Islands. When American forces retook Attu Island in May 1943, Tanaka was knocked unconscious by an artillery shell. He woke up in an American field hospital, his hands bound and his world destroyed. To return home after the war would be to return as a ghost.

At Camp Hood, a sprawling 200,000-acre training ground for tank destroyers, Tanaka spent his days hauling rocks and mending roads. While German and Italian prisoners often integrated into the local economy as laborers, the Japanese were kept separate, viewed with a mixture of intense suspicion and cultural bafflement. But Tanaka was observant. He noticed that the northwestern perimeter of the camp was watched by a single tower where a young guard spent more time reading pulp westerns than watching the wire.

On the evening of April 23, 1943, as the sun dropped behind the tower and blinded anyone looking west, Tanaka used a makeshift tool to part the chain-link fence. He slipped through and vanished. By the time roll call revealed his absence, he was already miles away, swallowed by the mesquite and cedar brakes.

The Cave and the Colonel

For two months, Tanaka lived like an animal. He hid in a limestone cave, surviving on creek water, fish caught with his bare hands, and prickly pear cactus. He watched the stars and wondered if he would ever speak to another human being again. In late June, driven by the gnawing desperation of starvation, he stumbled onto a small, 300-acre ranch owned by Earl McCullough.

McCullough was a man of few words and even fewer prejudices. A sixty-year-old widower and former cavalry officer, he was half-deaf from his time in the artillery during World War I. When he found a skeletal figure in rags eating cornmeal in his barn, he didn’t call the authorities. He lowered his revolver, looked at the desperate man, and asked a single word: “Hungry?”

What followed was a profound defiance of every military regulation of the era. McCullough fed Tanaka, gave him a place to sleep in the barn, and eventually provided him with clean ranch gear. A silent pact was formed. McCullough needed a hand to mend fences and haul feed; Tanaka needed a place to hide. They communicated through gestures and the shared rhythm of hard, physical labor.

Becoming Harry Thompson

As the war raged across Saipan and Okinawa, the ranch remained a bubble of strange, hard-earned peace. Tanaka learned the art of roping cattle and repairing windmills. When the news of Hiroshima’s destruction reached the ranch in August 1945, Tanaka’s world ended for a second time. His entire village had been vaporized.

“Japan don’t want you,” McCullough told him in a rare moment of loquacity. “Army don’t need you. You got a place here.”

Tanaka stayed. Over the next decade, McCullough taught him English with fatherly patience, using Zane Grey novels and livestock auction notices as textbooks. Tanaka became “Harry,” a hired hand supposedly from California. In a community still scarred by the war, McCullough’s reputation as a “straight shooter” acted as a shield for Tanaka. By 1950, Harry had saved enough to buy a small parcel of land, registering the deed under the name Harold Takashi Thompson.

The decades that followed were a masterclass in hiding in plain sight. Harry Thompson served on the school board, judged livestock at the county fair, and married a librarian named Linda. He became a fixture of the community—hardworking, quiet, and reliable. His past was sanded smooth by the routine of ranching, his former life becoming a collection of brittle memories hidden in the back of his mind.

The Unraveling of the Secret

The silence held until 1978, when Dr. Ellen Kaufman, a researcher from the University of Texas, began compiling oral histories of Texas POW camps. She noticed a persistent footnote in the records: Hiroshi Tanaka, escaped April 1943, presumed dead. No remains had ever been found. Her investigation eventually led her to a “strange fella” who had worked for McCullough.

When she confronted Harry Thompson at his ranch gate, the 73-year-old man didn’t run. He simply smiled a sad, distant smile and said, “Haven’t heard that name in thirty-five years.”

On his porch, Thompson told her everything—the escape, the cave, the years with McCullough, and the crushing realization that his home in Japan no longer existed. He showed her his original Japanese military identification, hidden in a tin box in the barn. But he made one request: “I’m Harry Thompson now. I’ve been Harry longer than I was Hiroshi.” Dr. Kaufman respected his wish, publishing her findings in an obscure academic journal under a pseudonym, where the story was largely forgotten.

The Final Transformation

Harry Thompson died in 1991 at the age of 86. His obituary listed him as a rancher and community leader, with no mention of the war or the empire he had once served. It was only after his funeral that his daughter found the truth: a small wooden box wrapped in oil cloth at the back of a closet. Inside was a photograph of a lean, sharp-faced young man in an Imperial Japanese Army uniform, a brittle letter in Japanese, and a hand-drawn map of Camp Hood.

Today, that wooden box sits in a quiet corner of the Camp Hood Historical Museum. Most visitors walk past it to see the tanks and the barracks, but those who stop find the story of a man who proved that identity is not a fixed point, but a river that can carve new channels through even the hardest stone. Hiroshi Tanaka’s story isn’t one of battlefield glory or military strategy; it is a story of survival, transformation, and the peace that can be found in the vast, silent hills of a country that was once his enemy, but eventually became his home. He died a Texan, but he lived a ghost—the man who vanished twice and found himself in the process.