Bruce Springsteen’s Cry From the Snow: How “Streets of Minneapolis” Became a Protest Anthem for Alex Pretti, Renee Good, and a Nation on Edge

In moments of national rupture, America has often turned to its artists not for policy prescriptions, but for moral clarity. When politics hardens into slogans and institutions retreat behind talking points, music has a way of cutting through the noise—naming grief, rage, and hope in a language people can feel. That is the space Bruce Springsteen stepped into on January 28 with “Streets of Minneapolis,” a raw, rapid-fire protest song written and released within days of the fatal shootings of Alex Pretti and Renee Good by federal agents.

Springsteen’s song did not arrive as a polished single after months of studio refinement. It arrived urgent, its edges intentionally rough, as if still warm from the writing desk. “I wrote this song on Saturday, recorded it yesterday and released it to you today,” Springsteen said in a statement. “It’s dedicated to the people of Minneapolis, our innocent immigrant neighbors and in memory of Alex Pretti and Renee Good. Stay free.” That signature—Stay free—was less a farewell than a summons.

What followed was not merely another entry in the Boss’s long catalog of political songs. “Streets of Minneapolis” became a lightning rod in a country already polarized by immigration enforcement, the use of federal force in American cities, and the widening gulf between official narratives and what citizens were seeing with their own eyes.

The Sound of Urgency: A Song Written in Days, Not Years

Musically, “Streets of Minneapolis” starts in familiar Springsteen territory: a folk foundation that recalls protest ballads of the 1960s. But it doesn’t linger there. A crunchy electric guitar pushes forward, an organ swirls underneath, and Springsteen’s voice grows more insistent with each verse. This is not nostalgia. It is acceleration.

The lyrics are blunt, even confrontational:

“King Trump’s private army from the DHS

Guns belted to their coats

Came to Minneapolis to enforce the law

Or so their story goes.”

Springsteen is not interested in euphemism. He names power, names institutions, names individuals. Later, the song turns directly to the killing of Pretti:

“Then we heard the gunshots

Then Alex Pretti lay in the snow, dead

Their claim was self-defense, sir

Just don’t believe your eyes.”

For Springsteen, the clash at the heart of the moment is epistemic: who controls the story. Official claims on one side. Bystander videos, eyewitness accounts, and grieving families on the other. The refrain—don’t believe your eyes—lands as an indictment not just of a single incident, but of a system that asks citizens to distrust what they see in favor of authority.

Minneapolis as Symbol—and Reality

Minneapolis is not new ground for American reckoning. From George Floyd in 2020 to the recent immigration enforcement surge, the city has become a symbolic and literal battleground over policing, federal power, and community resistance. Springsteen situates “Streets of Minneapolis” squarely within that lineage.

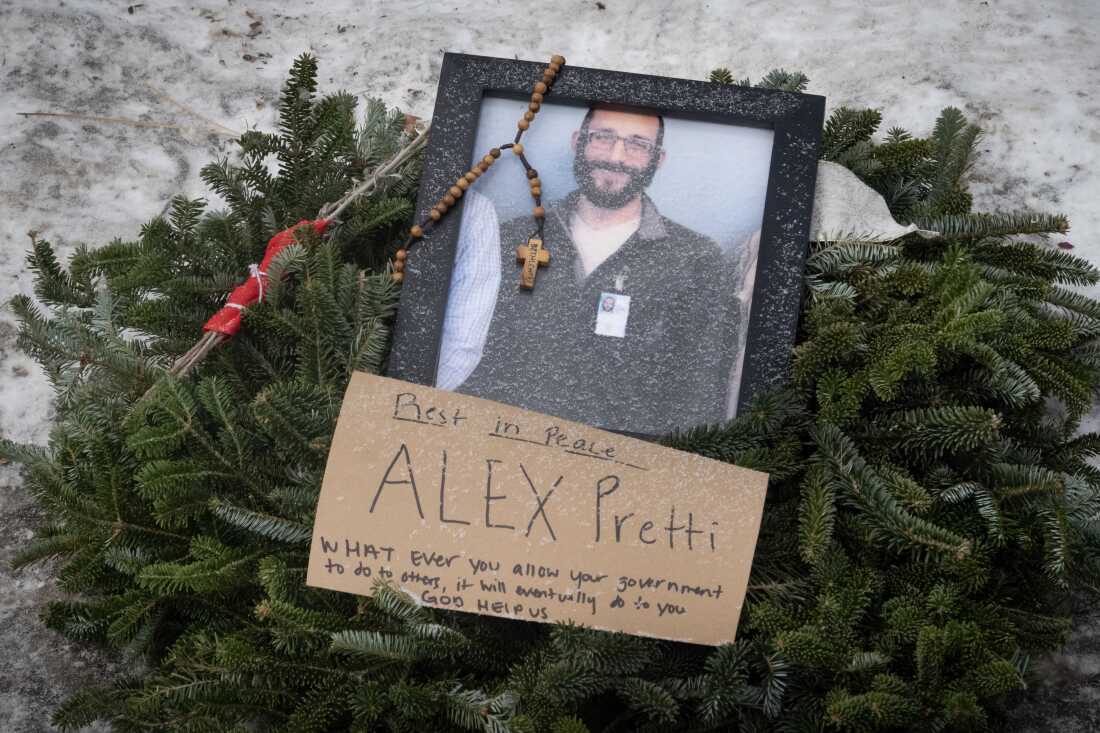

The shootings of Pretti and Good occurred amid what President Donald Trump described as the “largest immigration enforcement operation ever” in Minnesota. In early January, Good was killed by an ICE agent after officials claimed her vehicle was “weaponized.” Weeks later, Pretti—a 37-year-old ICU nurse who treated veterans—was killed during a confrontation with federal agents. In both cases, video evidence and witness testimony complicated, and in the eyes of many contradicted, early official accounts.

Springsteen’s song does not attempt to adjudicate every fact. Instead, it focuses on moral consequence: two Americans dead, families shattered, a city traumatized, and a widening trust gap between the public and those wielding state power.

Naming Names: Miller, Noem, and the Politics of Rhetoric

One reason “Streets of Minneapolis” drew immediate backlash from the White House is that Springsteen does not stop at abstract critique. He names Stephen Miller and Kristi Noem directly:

“It’s our blood and bones and these whistles and phones /

Against Miller and Noem’s dirty lies.”

Miller, the architect of the administration’s immigration policy, labeled Pretti a “terrorist” in social media posts shortly after the killing. Noem echoed that framing, calling Pretti a “domestic terrorist” and asserting that he approached officers with a pistol. Bystander videos showed Pretti holding a phone; DHS later said he was in possession of a handgun and magazines, but questions about the sequence of events remain central to ongoing investigations.

By naming Miller and Noem, Springsteen aligns himself with a tradition of protest music that refuses to anonymize power. This is reminiscent of his earlier political work—from “Born in the U.S.A.” to his speeches on democracy during the E Street Band’s European tour—where he has consistently argued that truth requires specificity.

The White House Response: “Random Songs with Irrelevant Opinions”

The administration’s response was swift and dismissive. A White House spokesperson said the administration was not focused on “random songs with irrelevant opinions,” emphasizing instead its priority of encouraging cooperation with federal law enforcement to remove “dangerous criminal illegal aliens.” DHS officials went further, suggesting they “eagerly await” songs dedicated to Americans killed by criminal undocumented immigrants.

This exchange underscored the very divide Springsteen was singing about. For critics, the administration’s response felt like deflection—sidestepping questions about use of force and accountability by reframing the conversation around crime statistics and border security. For supporters, Springsteen’s song was seen as celebrity grandstanding that ignored the dangers faced by federal agents.

But the cultural impact of “Streets of Minneapolis” suggested something else was happening. The song was not changing policy overnight. It was changing the emotional weather.

Jimmy Kimmel’s Tears and the Cultural Echo

Two days before Springsteen released the song, Jimmy Kimmel broke down in tears during his monologue while discussing Pretti and Good. “To the people of Minneapolis, to the Pretti family and the Good family,” he said, his voice cracking, “these people that were looking out for their neighbors—we want you to know you are not alone.”

Springsteen’s song and Kimmel’s monologue functioned as cultural mirrors, reflecting a grief and anger many Americans were struggling to articulate. In a media environment saturated with partisan framing, these moments cut through precisely because they were visibly human.

Art as Counter-Narrative

Protest music has always served as a counter-narrative to power. From Woody Guthrie to Nina Simone to Bob Dylan, artists have challenged official stories by insisting on lived experience. Springsteen, who once wrote that “nobody wins unless everybody wins,” is deeply aware of that lineage.

In “Streets of Minneapolis,” the counter-narrative is not abstract ideology but witness: whistles used by neighbors to warn of federal agents; phones raised to document; snow stained by blood; families left with questions. The song’s power lies in its refusal to sanitize those details.

The administration may dismiss it as irrelevant, but relevance is not measured by press releases. It is measured by resonance—and the song resonated because it spoke to a growing unease about federal force in domestic spaces and the criminalization of protest and observation.

Minneapolis, Immigration, and the Question of “Law and Order”

Springsteen’s lyrics repeatedly return to a question that has haunted American politics for decades: what does law and order actually mean?

At a January 17 performance, he put it plainly: “If you believe in the power of the law and that no one stands above it… If you believe you don’t deserve to be murdered for exercising your American right to protest… send a message to this president.”

For supporters of aggressive enforcement, law and order means border security and officer safety. For critics, it must also mean accountability, due process, and proportionality—especially when federal agents operate in American neighborhoods.

“Streets of Minneapolis” does not offer a technocratic answer. It offers a moral challenge: if law and order requires citizens to distrust their own eyes, what remains of democracy?

The Families at the Center

Lost amid policy debates are the families of Alex Pretti and Renee Good. Springsteen’s dedication brings them back to the center. Pretti’s parents have described their son as a “kindhearted soul” who wanted to make a difference. Good’s family has spoken of a mother whose life ended in a moment that still defies easy explanation.

By dedicating the song to them, Springsteen resists the abstraction that often follows tragedy. He insists on names, on memory, on the irreducible fact of loss.

Why This Song Matters

Will “Streets of Minneapolis” change immigration policy? Probably not directly. But it matters because it reframes the conversation. It reminds listeners that beyond statistics and slogans are streets, neighbors, and lives.

It matters because it challenges the idea that culture should stay silent in the face of state violence. It matters because it insists that patriotism is not obedience, but vigilance—the willingness to speak when ideals are endangered.

And it matters because it captures a moment when many Americans feel the ground shifting under their feet, unsure whether institutions meant to protect them still command their trust.

“Stay Free”

Springsteen closed his statement with two words: Stay free. In the context of “Streets of Minneapolis,” that phrase carries layered meaning. Freedom, here, is not merely the absence of constraint. It is the presence of truth, the courage to witness, and the refusal to accept narratives that erase human dignity.

Whether one agrees with Springsteen’s politics or not, the song stands as a document of a moment—January 2026—when art, grief, and protest converged. In the snow-covered streets of Minneapolis, Springsteen heard a cry. With “Streets of Minneapolis,” he answered it, adding his voice to a chorus that refuses to let the dead be forgotten or the living be silenced.

In a divided nation, that act alone ensures the song’s place—not just in playlists, but in the ongoing struggle over the soul of American democracy.