The Cowboy Cure: How a Texas Ranch Turned 17 German Child Soldiers into Brothers

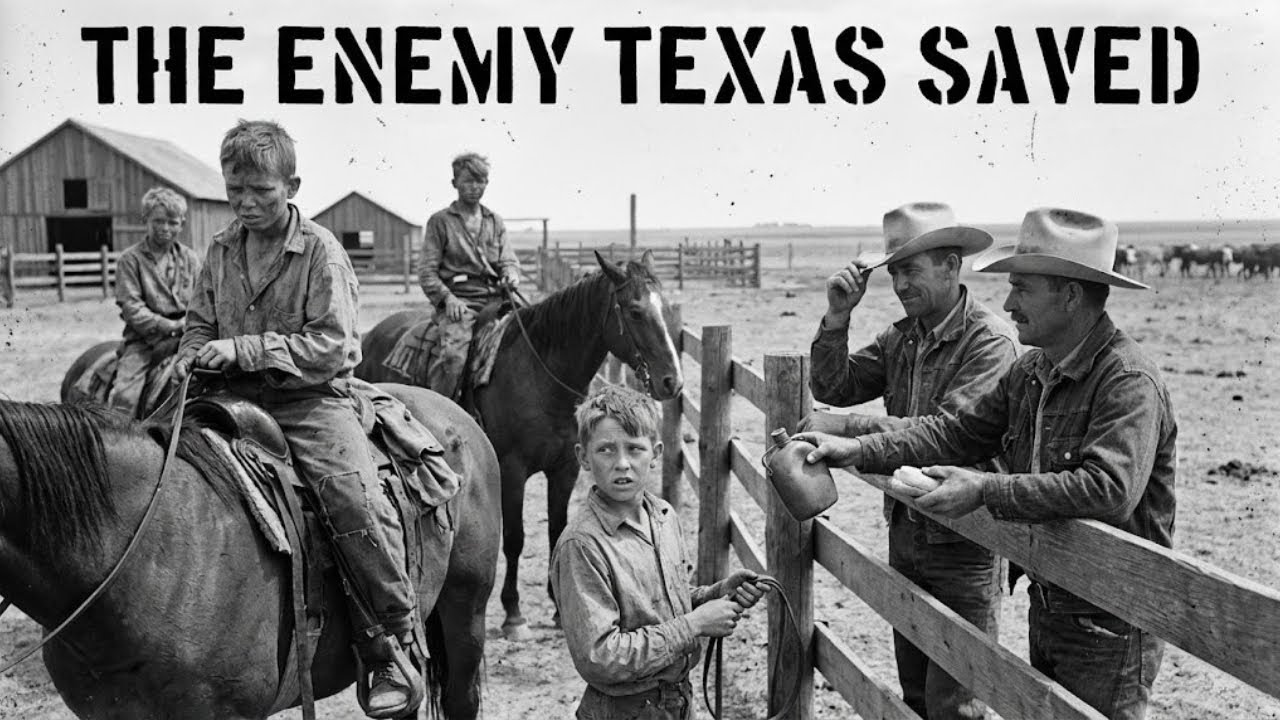

History is typically a ledger of loud moments—the roar of artillery, the thunder of political speeches, and the sharp lines of treaties signed in ink. But the most profound transformations often occur in the quiet margins, where the heat of ideology meets the cool reality of human connection. In the sweltering summer of 1944, a small cattle ranch outside Hebronville, Texas, became the stage for one of World War II’s most unlikely social experiments. It was here that seventeen German prisoners of war—most of them just boys in their mid-teens—discovered that the “savages” they had been trained to hate were, in fact, the mentors they desperately needed.

The Paradox of 1944

By July 1944, the global conflict had reached a point of exhaustion and desperation. While Allied forces were pushing through the hedgerows of Normandy, the United States was dealing with a massive domestic crisis: a catastrophic labor shortage. With millions of American men serving overseas, the agricultural backbone of the country was failing. Crops were rotting in the fields, and cattle ranches sat empty.

The solution was as practical as it was controversial. Nearly 400,000 German prisoners were being held in camps across America, from Virginia to California. Washington made the calculated decision to put these prisoners to work. However, the group sent to the Hardwick ranch in Texas were not the hardened veterans of the Wehrmacht or the SS. They were the remnants of the Volkssturm and the Hitler Youth—fourteen, fifteen, and sixteen-year-old boys who had been swept up in Germany’s final, desperate levy.

These boys arrived on American soil with hands still blistered from youth training camps and minds filled with terrifying propaganda. Berlin had told them that American cowboys were lawless killers who would torture them for sport. When they rolled through the ranch gate on July 14, 1944, they weren’t just entering a new country; they were entering what they believed was their certain execution.

Rusty and the Art of Gentling

Waiting for them at the gate was Rusty—real name Russell Kowalski. A sixty-three-year-old son of Polish immigrants, Rusty was a man who had spent forty years judging others by the quality of their work rather than the language they spoke. He saw the terror in the boys’ eyes—a look he recognized from colts separated from their mothers—and he made a choice that would define the rest of their lives.

He didn’t shout. He didn’t reach for a whip. He simply nodded toward the barn and said one word: “Work.”

The first few days were a collision of worlds. The boys had been raised on a diet of rigid hierarchy, where every mistake was met with humiliation or physical punishment. When a thin fifteen-year-old named Thomas struggled to lift a forty-pound Western saddle, he braced for a blow. Instead, he received a lesson. Rusty stepped forward and showed him how to brace the weight against his hip, letting his legs carry the burden his arms couldn’t.

This pattern repeated itself daily. If a boy fumbled a rope or fell from a horse, the cowboys didn’t humiliate them; they laughed good-naturedly, helped them up, and retied the knots slowly so the boys could learn. To the teenagers of the Reich, this was a revolution. They were being taught that strength didn’t require cruelty, and that masculinity was built on competence, not conquest.

Harmonicas and Heritage

By the third week, the atmosphere of the ranch had shifted from a prison camp to a mentorship program. The boys began to laugh. Around the evening campfire, the ranch hands—men like Jimmy, whose own brother was fighting in Europe—treated the prisoners like green recruits. They shared tobacco, taught them trail songs, and showed them how to roll cigarettes.

One evening, a boy named Otto pulled a harmonica from his boot—a forbidden souvenir he had carried since his capture in France. He played a mournful melody from the Rhine Valley. The cowboys listened in a profound silence that bypassed the battle lines of the war. When he finished, Jimmy picked up his guitar and played a Texas ballad. In that shared musical space, the ideology of the “enemy” began to disintegrate.

Jimmy had every reason to hate these boys. But as he watched them struggle with the Texas heat and the demanding work of mending fences, that hate became impossible to sustain. They weren’t monsters; they were children who had been fed a diet of lies and sent to die.

The Cowboy Spirit

The work was grueling. Herding cattle across 12,000 acres of mesquite-choked scrubland required a focus and resilience that the Hitler Youth “summer camps” had never truly tested. Barbed wire tore their hands, and the dust choked their lungs. But for the first time in their lives, the boys were doing “honest work.” There was no propaganda to fix a fence; there was only a tool, a task, and the satisfaction of a job well done.

Rusty noticed the transformation. Thomas, once a shivering boy, now handled a horse with a quiet confidence that bordered on the professional. Otto could rope a calf faster than some of the veteran hands. They were becoming cowboys, not by wearing the costume, but by adopting the spirit. The swagger of the Nazi youth was being replaced by the steady, bow-legged gait of a Texas ranch hand.

This transformation was not without its risks. In November, the camp commandant visited the ranch, warned by reports of “excessive fraternization.” He reminded the ranch owner, Samuel Hardwick, that these were enemy combatants, not neighbors. But the spirit of the ranch couldn’t be regulated. While the rules of the Geneva Convention were followed—locked bunkhouse doors and armed guards on supply runs—the cowboys refused to turn off their humanity.

The Texas Lesson

As the war in Europe collapsed in early 1945, the ranch became the only stable point in a world that was vanishing for the boys. Letters from home stopped entirely, leaving them to wonder if their families were alive or dead in the ruins of German cities.

Thomas, standing by the corral one evening, said something to Rusty that summarized the entire experience: “Berlin told us to conquer the world. Texas taught us how to ride it.”

They had arrived believing in domination—believing that strength meant crushing others. But the cowboys had shown them a different model. Power could be generous. Strength could be patient. Respect was earned through deeds, not birthright. It was a fundamental rewiring of the programming they had received since birth.

The Final Roundup

When Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the ranch gathered around a crackling radio to hear the news. The boys sat in a stunned, heavy silence. They weren’t grieving for the regime; they were grieving for their childhoods and the country they no longer recognized. The cowboys, many of whom had lost friends or family to the war, gave them the space to mourn. They understood that the boys were crying for everything they had lost.

In June, the orders for repatriation finally arrived. The boys were going back. The news hit the ranch with the weight of an exile. The Hardwick ranch had become home; the cowboys had become the fathers and brothers many of the boys no longer had.

On the night before they left, Hardwick hosted a final meal—steaks grilled over mesquite, peach cobbler, and cornbread. As they ate, Rusty stood up. He didn’t make a grand speech. He simply shook each boy’s hand and told them that as long as the Hardwick ranch was standing, they would always have a place to work.

A Legacy Beyond the Wire

The boys returned to a Germany of rubble and ash. But they carried the Texas sunset in their hearts. Many, like Thomas, eventually immigrated back to the United States, working ranches across the Southwest and using the skills Rusty had taught them. Otto returned to rebuild his hometown, bringing American pragmatism to a broken nation. Emil found his mother and spent the rest of his life as a farmer, teaching his own children the values of respect and hard work he had learned in Hebronville.

Rusty continued to work the land until his body gave out. He rarely discussed that summer of 1944. If asked, he would simply say they were “good hands.” But his choice to see the boys instead of the enemy created a ripple effect that lasted for generations.

The Hardwick ranch is gone now, paved over by developers. But the story remains a powerful reminder that even in the darkest hours of human history, humanity is a choice. Berlin had told the boys to conquer, but Texas showed them how to build. And in that simple difference lay the salvation of seventeen young lives. In the dust of Hebronville, a legacy was forged not in fire, but in the patient tie of a rope and the shared melody of a harmonica.