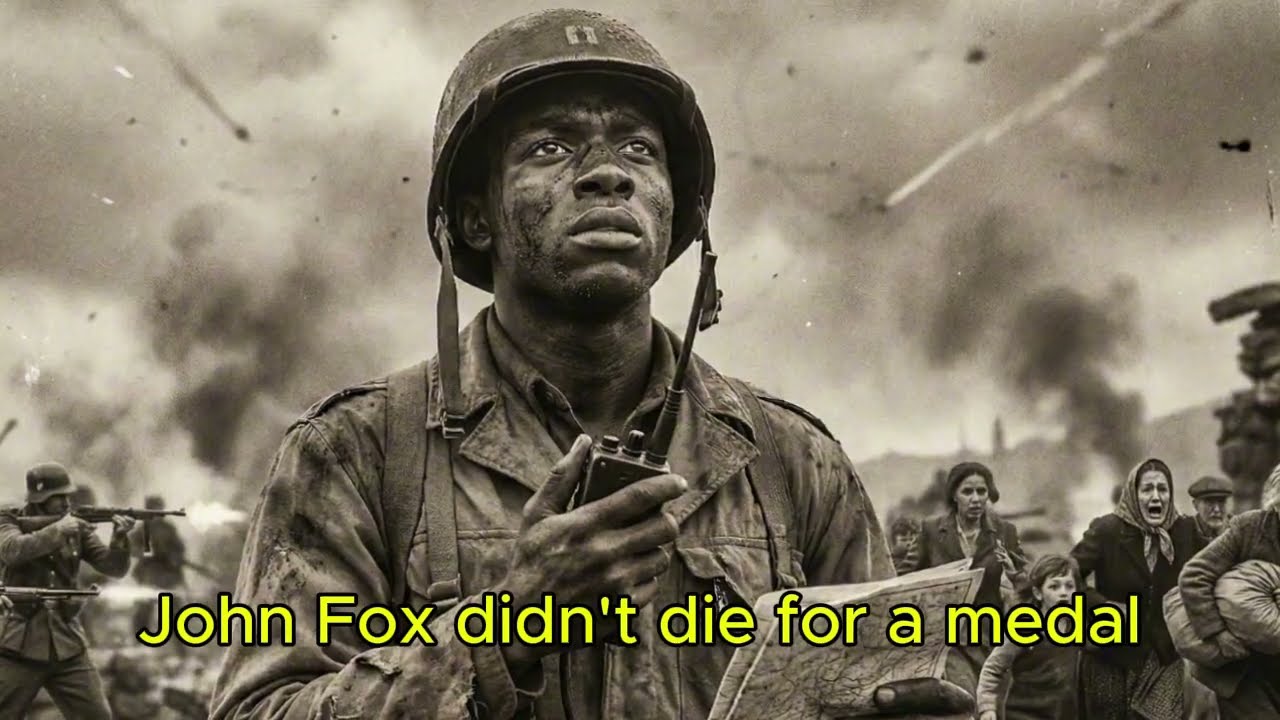

Surrounded by 600 Enemies, He Made the Ultimate Call to Save Them All

“Fire It”: The Staggering Sacrifice of Lieutenant John Fox, the Black Officer Who Called Artillery on Himself to Stop 600 Germans

In the high-altitude, bone-chilling silence of the Tuscan mountains in December 1944, the village of Sommocolonia became the stage for an act of valor so profound it would take the United States government half a century to properly acknowledge it. It is a story that strips away the tidy narratives of textbook history to reveal the raw, bleeding edge of the human spirit. At its center stands First Lieutenant John R. Fox, a man who didn’t just wear the uniform of the 92nd Infantry Division—the legendary “Buffalo Soldiers”—but who carried the weight of a nation’s prejudice and a soldier’s ultimate duty in his final, steady hand.

John Fox was 29 years old, a man of intellect and science who had graduated from Wilberforce University. In the segregated Army of World War II, a Black officer was an anomaly, a target of both enemy fire and domestic disdain. The 92nd Division was often viewed by the military brass as an “experiment,” a unit many expected—and some perhaps even hoped—would fail. But on the morning of December 26, 1944, John Fox would prove that courage has no color, and that the most powerful weapon on the battlefield is a man who has made peace with his own end.

The Ghost Offensive: Operation Wintergewitter

The day after Christmas, the air in Tuscany was so cold it felt like broken glass in the lungs. The American lines were stretched thin, and many soldiers were attempting to find a moment of post-holiday respite. They were unaware that the German High Command had launched “Wintergewitter” (Winter Storm), a desperate, secret offensive designed to puncture the Sergio Valley.

The Germans didn’t come with the roar of tanks. They came as ghosts. Elite Austrian mountain troops infiltrated Sommocolonia disguised as local peasants, wearing heavy coats and slumping like tired farmers. They walked right past American checkpoints, smiling and nodding, their automatic weapons concealed. Once deep inside the village, they shed their disguises. Sommocolonia exploded into a slaughterhouse.

The American defense collapsed in a fog of confusion. Soldiers were shot in their bunks; radio networks were jammed with the screams of men calling for help that wasn’t coming. As the majority of the U.S. forces began a necessary but chaotic retreat, Lieutenant John Fox did something that defied military logic. He climbed.

The Eyes in the Tower

Fox was a forward observer for the 598th Field Artillery Battalion. In the hierarchy of combat, a forward observer is a paradox: they are “ghosts” who hold the power of lightning but are physically vulnerable in a fragile room. Fox made his way to the second floor of a sturdy stone house with a commanding view of the village square. He lugged his heavy radio, his maps, and his carbine, and he locked the door.

From his perch, Fox watched the village burn. He saw the gray-clad German soldiers swarming the streets like ants. He saw them setting up mortar positions in the town square and dragging American prisoners into the cold. He realized the tactical nightmare: if the Germans secured Sommocolonia, they would control the high ground of the entire valley, effectively splitting the American line in half.

A retreating sergeant yelled up to the house, urging Fox to come down while a small gap still existed in the German line. Fox looked at his radio and then at the valley below. He knew that if he left, the American artillery would be blind. “No,” he replied. “I’m staying.”

The Loneliness of the Long Shot

By mid-morning, Fox was the only organized resistance left in his sector. He put on his headset and keyed the microphone. Miles away, the gun crews of the 598th stood ready.

Fox began to speak numbers—coordinates, elevation, direction—with the calm precision of a professor giving a lecture. The 105mm howitzers roared into life. The first shells landed in the streets below, sending ancient cobblestones flying. The German advance paused, confused by the surgical accuracy of the fire. Fox adjusted his aim: “Right 100, drop 50.” The next volley wiped out a German mortar team in the plaza.

But the Germans were veterans. They quickly realized someone was spotting for the guns. A sniper bullet cracked against Fox’s window frame, spraying him with stone dust. He didn’t flinch; he simply moved deeper into the shadows and kept talking. “Target is infantry in the open. Fire for effect.”

The Germans became desperate. They stopped being subtle and brought up heavy weapons to blast the facades of the buildings overlooking the square. Fox was essentially sitting inside a bell being rung by sledgehammers, yet he continued to call down fire, buying every precious second for his division to dig a new defensive line in the valley.

“Fire It”: The Final Command

By noon, the situation moved from desperate to impossible. Sommocolonia was swarming with an estimated 600 German soldiers. They had identified Fox’s house. A squad of Austrian troops shattered the heavy wooden door on the ground floor. Fox heard the splintering wood and the heavy thud of boots on the stairs. He was trapped. There was no back exit, no escape route—only the window, the radio, and the enemy climbing toward him.

This is the moment where most men would wave a white flag. But John Fox knew the reality of his situation; he knew that surrender likely meant a ditch and a bullet. He decided he would die as an officer of the United States Army.

He keyed the radio. “Artillery,” he said, his voice steady. “Adjust fire. Converge on my coordinates.”

On the other end, the operator—his friend, Lieutenant Otis Burton—froze. “Fox, say again. That is your position. We can’t do that.”

“There are more of them than there are of us,” Fox replied. “Give them hell.”

The battalion commander got on the line, needing to verify. He couldn’t believe a soldier was ordering his own death. “Fox, is this a mistake? Verify your last. That is right on top of you.”

Fox didn’t look at the door as it began to buckle under the German boots. He didn’t look at the grenade pin he heard clicking in the hallway. He looked out the window at the men he was protecting. He keyed the mic one last time.

“Fire it.”

The Thunder over Sommocolonia

The response was a thunderclap that shook the very foundations of the mountains. The 598th Field Artillery Battalion unleashed a relentless barrage of high explosives. The sky above Sommocolonia tore open. The first shells hit the roof of the house, then the courtyard. Stone turned to powder. The Germans in the hallway didn’t have time to scream; the ones in the street were vaporized.

It was a curtain of steel brought down by one man’s will. To the Americans retreating in the valley, the sound was terrifying but acting as a shield. The German pursuit stopped dead. The elite mountain troops, battered and confused by an enemy willing to drop the sky on his own head, pulled back. The line held.

When American troops and Italian partisans re-entered the ruins of Sommocolonia on January 1, 1945, they found a graveyard. They dug through the pile of stones that used to be the tower and found the body of Lieutenant John R. Fox. He was still by the window. But he wasn’t alone. Surrounding his position in a perfect circle were the bodies of nearly 100 German soldiers.

The 50-Year Journey to Justice

To the people of Sommocolonia, John Fox was a savior. They knew he had sacrificed his life to prevent their execution and the occupation of their homes. They crossed themselves as his body was carried away. But to the U.S. Army of the 1940s and 50s, he was just a casualty of color.

For decades, his file sat in a dusty cabinet. His widow, Arlene, received a telegram and a flag, but the magnitude of his sacrifice was ignored by a military not yet ready to award its highest honor to a Black man.

It took until 1997 for the truth to surface. Following a massive review of racial disparity in World War II awards, President Bill Clinton stood at a podium in the White House. He called the name of John R. Fox. Arlene, then an elderly woman, accepted the Medal of Honor on behalf of the husband who had stayed in the tower so others could go home.

Today, a monument stands in Sommocolonia, near the spot where the house once was. The locals still bring flowers to it every year. John Fox didn’t die for a medal or for the generals who doubted him. He died for the man standing next to him and for the principle that courage has no color. He remains a beacon for the truth that when the darkness closes in, one man can be the light—even if he has to burn himself out to do it.