The Elite Black American Soldiers Patton Hesitated to Deploy — October 1944

October 1944 descended on Europe like a shroud, cold and unrelenting. In a stone building outside Verdun, the boardrooms of the Allied High Command were thick with cigarette smoke and the heavier weight of bad news. Maps were pinned to walls like wounded animals, corners curling, grease-pencil arrows smeared and redrawn so many times they had begun to look like scars.

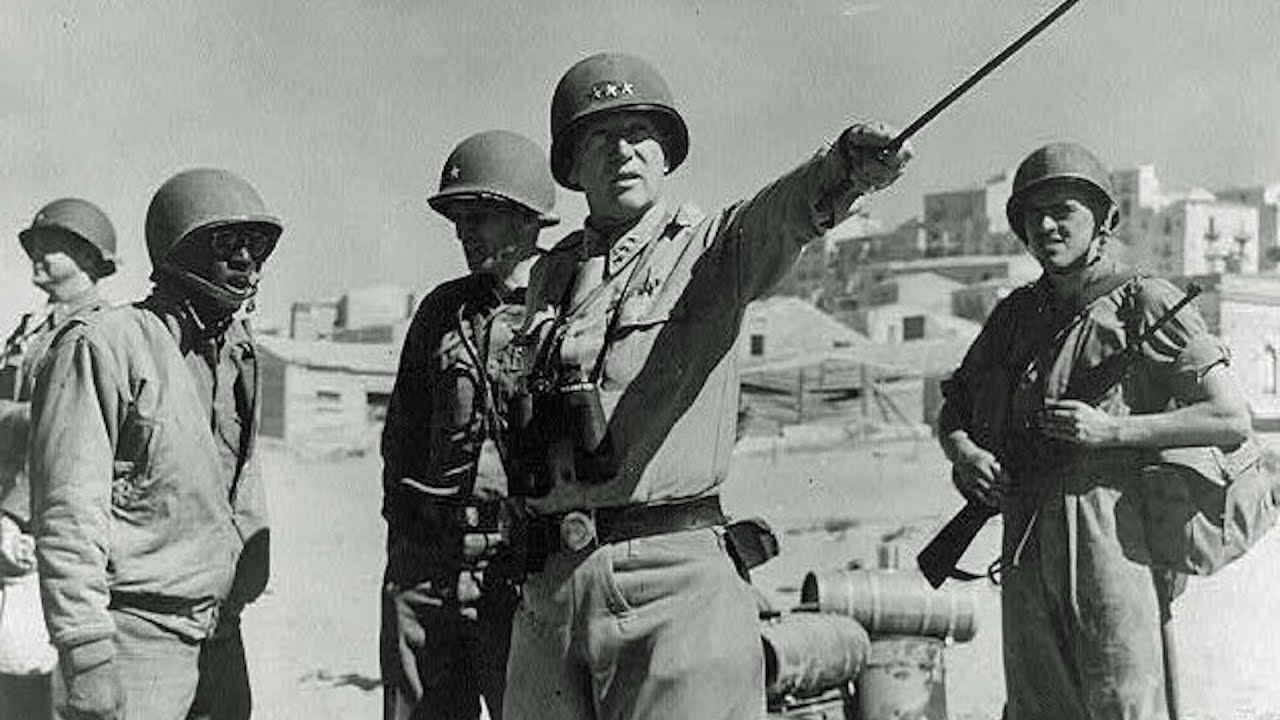

General George S. Patton stood apart from the others, his polished helmet resting on the table beside him, his ivory-handled pistols hanging silent at his hips. The men in the room watched him carefully. Patton was known for explosions—of temper, of profanity, of brilliance—but now he was quiet. He stared at the map the way a doctor stares at an X-ray that confirms the diagnosis he didn’t want to make.

He was running out of time.

And worse, he was running out of tanks.

His Third Army had smashed across France with a speed that stunned even its own commanders, but momentum had a cost. The Shermans were burned out, thrown tracks, blown apart by German 88s. Replacement vehicles were trickling in too slowly. Fuel was rationed. Men were exhausted. Winter was coming, and the enemy was digging in.

Across the Atlantic, and now scattered through muddy staging grounds in England and France, sat a reserve of power the United States Army had trained, equipped, and then quietly ignored. They drilled. They waited. They listened to rumors of white units shipping out while they remained behind.

They were strong. They were eager. They were trained on the same M4 Shermans as every other tanker unit in the U.S. Army.

But they were Black.

The 761st Tank Battalion.

They called themselves the Black Panthers.

Before the Germans would ever learn to fear that name, the American military establishment had to overcome something it had never truly confronted before: its own fear of what might happen if Black men were allowed to fight—and win.

The Army of 1944 was segregated by law and by habit. It was built on a lie repeated so often it had hardened into doctrine. Black soldiers, the lie went, lacked the intelligence for mechanized warfare, the discipline for armored combat, the courage for sustained frontline fighting. They were suited for labor, not leadership. Support, not shock.

They drove trucks. They cooked meals. They buried bodies.

They were not meant to kill Nazis from inside a thirty-ton machine of steel and fire.

Patton knew all this. He had grown up in it. He had spoken it himself, more than once, in moments of unguarded honesty. But Patton was many things before he was a politician or a philosopher. Above all else, he was a pragmatist. And pragmatism had a way of burning away illusions.

He looked at his depleted divisions.

Then he looked at the fresh, untested battalion of Black tankers waiting on the sidelines.

He knew the risks weren’t on the battlefield. They were in Washington. In newspapers. In whispered conversations back home. Sending Black men to do a white man’s job—as society defined it then—was political dynamite.

But the Germans weren’t waiting for America to sort out its conscience.

They were fortifying villages, laying mines, zeroing artillery. The Ardennes loomed dark and quiet, like a held breath. Patton needed killers.

So he made the call.

But he didn’t just send a piece of paper.

He went to see them.

To understand what happened when Patton stood before the men of the 761st, you had to understand where they came from.

Camp Hood, Texas, was less a training post than a crucible. The sun there was merciless, baking the red clay into something harder than concrete by day and turning it into sucking mud when the rains came. For two long years, the men of the 761st trained for a war they weren’t sure they would ever be allowed to fight.

White tank units passed through Camp Hood quickly, trained, stamped, and shipped overseas in a matter of months. The Black Panthers stayed.

They ran the same drills again and again until muscle memory replaced thought. They learned every inch of the Sherman—the engine’s whine, the recoil of the main gun, the smell of hot oil and cordite. They learned how to repair a broken track in the dark, under fire, with numb fingers. They learned how to load, fire, and reload until their arms shook.

They didn’t just learn to drive tanks.

They learned to make them dance.

And outside the training grounds, they learned another lesson entirely.

Texas in the 1940s did not hide its hatred. Signs told them where they could and could not go. White civilians reminded them daily of their place. Even within the Army, they were insulted, doubted, and sometimes outright sabotaged. Equipment went missing. Promotions stalled. Punishments came swiftly and unfairly.

The men of the 761st absorbed it all in silence.

They didn’t have the luxury of protest. What they had was pride, and something sharper underneath it: a cold, patient fury.

If the Army would not trust them, they would become impossible to ignore.

Patton arrived on a gray morning, his jeep splashed with mud, his arrival sending a ripple through the battalion like an electric current. The men stood at attention, rows of Black faces staring forward, expressions carved from stone.

Patton walked the line slowly.

He looked at their boots, their uniforms, their hands. He stopped in front of one tank crew, then another. He asked questions—not polite ones, not easy ones. He asked about gunnery ranges, fuel consumption, breakdown rates. He asked what they would do if their commander was killed. He asked how long it took to change a transmission.

The answers came back fast and precise.

Finally, Patton stopped and addressed them all.

“Men,” he said, his voice rough and unpolished, “I don’t care what color you are. I don’t care where you’re from. I only care about one thing.”

He paused, letting the silence stretch.

“Can you kill Germans?”

A beat passed.

Then, as if from a single throat, the answer came.

“Yes, sir.”

Patton nodded once.

That was enough.

When the 761st finally crossed into combat, it wasn’t with fanfare. There were no headlines. No bands. Just cold rain and the sound of artillery in the distance.

Their orders were simple and brutal: support infantry, take towns, keep moving.

Their first engagements were small, sharp, and deadly. A hedgerow here. A crossroads there. German anti-tank teams learned quickly that the Black Panthers did not hesitate. They advanced under fire, maneuvered aggressively, and when one tank was hit, another took its place without slowing.

Losses came early.

A Sherman burned on the edge of a village, black smoke clawing at the sky. A gunner killed by a sniper’s round through the vision slit. A driver crushed when his tank slid into a ditch under artillery fire.

The men grieved briefly.

Then they kept moving.

Word spread along the front, passed quietly from unit to unit. The Black tankers fought hard. They didn’t break. They didn’t pull back unless ordered. They took ground others couldn’t hold.

The Germans noticed too.

Enemy prisoners spoke of Panthers—confused at first, mistaking the name for the German tank. Then they learned. These Panthers were something else entirely.

They were relentless.

For the men of the 761st, every battle carried two wars inside it. One against the enemy in front of them. The other against the doubt behind them. Every mistake would confirm the lie. Every success chipped away at it.

So they allowed themselves no mistakes.

They fought through mud that swallowed tracks and snow that froze fingers to steel. They pushed into towns reduced to rubble, where every cellar might hide a Panzerfaust. They learned to read the land, to smell an ambush before it sprang.

Patton watched the reports with growing intensity.

What he felt was not surprise.

It was something closer to dread.

Because the Black Panthers were not just good.

They were devastating.

And Patton understood the implication before anyone else did. If these men proved themselves beyond doubt, then the old excuses—the old structures—would collapse. You could not send men like this home and tell them they were second-class.

Perhaps that was the fear that had stayed his hand.

Not that they would fail.

But that they would succeed too completely.

The winter offensive loomed.

The Ardennes waited.

And the Black Panthers rolled forward, into history, their first battle not against the Wehrmacht—but against the very nation whose flag flew from their tanks.

The snow came early that year.

It fell quietly at first, dusting the ruined villages and frozen fields with a thin white layer that made everything look peaceful from a distance. Up close, it only made the war crueler. Engines struggled in the cold. Oil thickened. Fingers went numb on metal triggers. Wounds that might have been survivable in summer turned fatal when the cold crept into bone and blood.

For the men of the 761st Tank Battalion, winter did not mean rest. It meant validation.

They were attached to Patton’s Third Army just as the pressure along the front intensified. German resistance stiffened, especially in the forests and narrow roads where tanks were vulnerable and infantry clung desperately to every inch of ground. The Black Panthers were sent where progress stalled, where commanders needed a hammer instead of a scalpel.

Their tanks rolled at dawn.

Sergeant Elijah Thompson sat inside his Sherman, breath fogging the interior despite the engine’s heat. He had grown up in Georgia, red dirt and cotton fields, a place where a Black man learned early how to keep his head down and his mouth shut. Inside the tank, there was no room for that kind of silence. Every man depended on the others. Every order mattered.

“Driver, forward slow,” he said, voice steady through the intercom.

The tank crept ahead, tracks crunching over frozen earth. Somewhere in the trees, a German gun waited.

The first shot came without warning.

A flash. A scream of metal. The tank to their left took the hit, its turret snapping sideways as flames burst from the engine compartment. Thompson flinched, then forced himself to breathe.

“Target, eleven o’clock, tree line,” the gunner shouted.

“Fire.”

The Sherman rocked as the 75mm roared. The shell tore through the trees, splintering trunks, scattering men. Machine guns joined in, raking the forest edge until nothing moved.

They advanced again.

No cheering. No celebration.

Just movement.

That was how the 761st fought. Methodical. Ruthless. Professional. They did not waste ammunition, and they did not waste lives—not theirs, not when discipline could prevent it.

But discipline did not mean mercy.

German units learned quickly that surrendering to the Black Panthers was safer than fighting them. Those who chose the latter rarely lived long enough to reconsider.

Reports filtered back to headquarters daily.

“761st advanced under heavy fire.”

“Enemy anti-tank positions eliminated.”

“Objective secured.”

At first, officers read them with mild curiosity. Then with respect. Then with something approaching awe.

Patton read every line.

He did not praise them publicly. He did not single them out in speeches. But he began assigning them harder tasks. More dangerous roads. More critical objectives.

They never refused.

And they never failed.

By December, the Germans launched their last gamble: a massive counteroffensive through the Ardennes Forest. The surprise was total. American lines buckled. Units fell back in confusion. Snowstorms grounded aircraft and turned roads into ice-choked traps.

The Battle of the Bulge had begun.

The 761st was thrown directly into the chaos.

They fought in conditions no training could fully prepare them for. Visibility dropped to yards. Mines lay hidden under snow. German armor lurked behind ridges and village ruins, waiting for point-blank shots.

Tank after tank was lost.

Crew after crew burned.

Still, the Panthers pressed on.

They supported surrounded infantry units, breaking through encirclements where others could not. They held roads vital to Patton’s rapid counterattack, sometimes fighting for days without relief. When fuel ran low, they siphoned from wrecks. When ammunition ran out, they scavenged from the dead.

One night, under a sky lit orange by distant fires, Thompson’s tank took a direct hit.

The blast knocked him unconscious.

When he came to, the tank was filled with smoke and screams. The driver was dead. The loader was bleeding badly, shrapnel embedded in his chest. The engine was on fire.

Thompson dragged the wounded man out, coughing, half-blind, and collapsed in the snow as the tank exploded behind them.

German infantry were close.

Too close.

Thompson picked up a rifle from the ground and stood over his wounded crewmate.

He did not think about Texas. Or Georgia. Or signs that said COLORED ONLY.

He thought about the months of waiting. About being told he wasn’t good enough. About every doubt that had ever been placed on his shoulders.

When the Germans came out of the smoke, he fired.

By morning, the road was still in American hands.

Losses mounted.

The 761st had entered combat with nearly 700 men. By the time the Bulge began to recede, a staggering number were dead or wounded. Some companies were reduced to half strength. Faces disappeared from mess lines. Names were crossed off rosters.

There was no replacement pool waiting behind them.

They fought on anyway.

Patton visited the front again in January. This time, he did not challenge them. He did not test them.

He simply stood in the cold, helmet pulled low, and watched the battered tanks roll past.

When an aide remarked on the battalion’s casualties, Patton replied quietly, “They’ve earned every mile they’ve taken.”

It was the closest thing to an apology he would ever give.

By spring, the German army was breaking.

The Black Panthers crossed rivers, smashed through rearguards, and pushed deeper into enemy territory. Villages surrendered without a fight when their tanks appeared. White units that had once doubted them now asked for their support.

The irony was not lost on the men of the 761st.

They were trusted with victory abroad, yet still barred from restaurants and restrooms back home.

In April 1945, the war ended.

The guns fell silent.

The men of the 761st did not celebrate wildly. They stood among the ruins, exhausted, grieving, proud.

They had fought 183 consecutive days in combat.

They had proven every lie false.

And then they went home.

Home did not greet them as heroes.

There were no parades. No medals pinned in front of cheering crowds. Many returned to segregation, to discrimination, to the same closed doors they had left behind.

But something had changed.

Quietly. Permanently.

The story of the Black Panthers spread from veteran to veteran, from unit to unit. It reached young men who would later march, protest, and demand the rights their fathers had earned in blood.

Patton died convinced he had commanded some of the finest soldiers of the war.

America took longer to admit it.

But history would not forget.

The 761st Tank Battalion had entered the meat grinder and emerged as one of the most ruthless, effective armored units in the European Theater—not because they were Black, and not despite it, but because they were soldiers who refused to be anything less than excellent.

They fought two enemies.

They defeated both.

The journey home was quieter than the journey to war.

The ships crossed the Atlantic under calm skies, gray hulls cutting through steel-colored water. For the men of the 761st Tank Battalion, the ocean felt wider than it had before, heavier with unspoken thoughts. They leaned against railings, watched gulls wheel overhead, and tried to imagine what waited for them on the other side.

Victory had a strange taste.

They had won the war they were sent to fight. They had crushed the enemy. They had survived the forests, the snow, the fire. Yet no one spoke openly about what came next. No one asked what kind of welcome they would receive.

Because deep down, they already knew.

Sergeant Elijah Thompson stood on deck as the coastline of America emerged from the fog. The Statue of Liberty rose in the distance, green and unmoving, her torch raised high. Men gathered beside him, some smiling, some silent.

“Looks the same,” someone muttered.

Thompson nodded.

It did.

The trains carried them south, west, back toward places with familiar names and old rules. Uniforms that had earned respect overseas meant little here. In some towns, white civilians stared at them with suspicion. In others, with open hostility.

At one station, Thompson stepped off the train to stretch his legs.

A sign hung above the water fountain.

COLORED.

He stared at it longer than necessary.

A week earlier, he had commanded a tank under fire. He had stood his ground against armed men who wanted him dead. He had helped break the back of the most dangerous army in Europe.

Now he was being reminded where he belonged.

He drank anyway.

The Army demobilized the 761st quietly.

There were no headlines announcing their return. No ceremonies to mark their sacrifice. A few medals were awarded behind closed doors, often without fanfare. Officers shook hands. Paperwork was signed.

And just like that, the Black Panthers ceased to exist as a unit.

Men scattered back into civilian life.

Some went north to factories and shipyards. Some returned to farms and small towns. Some carried wounds that never healed—shrapnel in bone, nightmares in the dark.

They told their stories to families who listened with pride and disbelief.

Most of America did not listen at all.

Years passed.

The war became something people talked about in past tense, a finished chapter. History books praised generals, strategies, decisive battles. The names of white units were printed in bold. Photographs showed smiling soldiers in clean uniforms.

The 761st was rarely mentioned.

But among those who knew, the legend endured.

Former infantrymen spoke of Black tanks that came when hope was gone. Officers remembered a unit that never complained and never broke. German veterans remembered the Panthers with something like fear.

The men themselves carried it quietly.

They gathered occasionally—reunions in small halls, churches, union buildings. Hair grayed. Backs bent. But when they talked about the war, something hardened behind their eyes.

They remembered the smell of burning fuel.

They remembered the sound of shells hitting armor.

They remembered proving the world wrong.

In the 1950s and 1960s, America began to change.

Slowly. Painfully.

Young Black men marched in the streets, demanding rights that had been denied for generations. Some were beaten. Some were jailed. Some were killed.

Among the crowds stood veterans.

Men who had worn the uniform.

Men who had fought for freedom abroad and were now demanding it at home.

Elijah Thompson watched one march from the sidewalk, his son beside him. The boy was tall, serious, his eyes bright with conviction.

“Dad,” the boy asked, “did you ever think it would come to this?”

Thompson thought of Camp Hood. Of Patton’s stare. Of the Ardennes in winter.

“I always knew it would,” he said. “I just didn’t know when.”

Recognition came late.

Decades late.

In 1978, long after many of the men were gone, the 761st Tank Battalion was finally awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. The words were formal. The ceremony was small. But for those who lived to see it, something settled at last.

They had not imagined it.

They had not exaggerated.

They had done what they said they did.

At the ceremony, Thompson stood with a cane in his hand, his uniform pressed one last time. When the citation was read, his throat tightened