The Finnish Farmer Who Became a Wartime Legend — 542 Enemy Soldiers, Never Once Seen

I. Introduction: The Ghost in the Snow

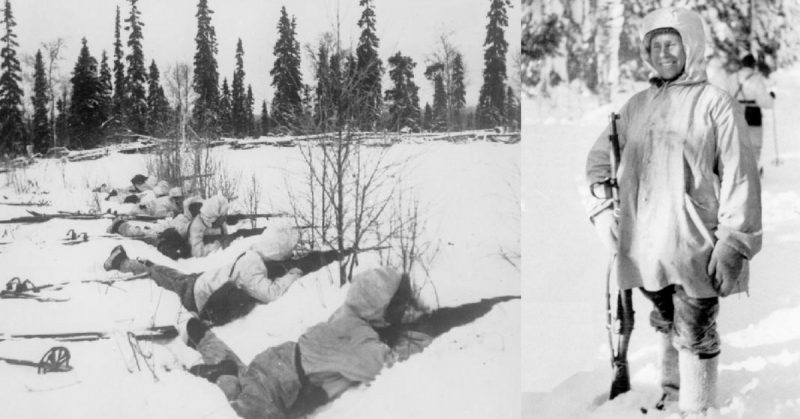

War is often remembered for its grand strategies, its generals, and its sweeping movements of armies. But occasionally, history pivots on the actions of a single, unassuming individual—someone whose quiet determination and extraordinary skill change the course of events. In the frozen forests of Finland during the Winter War of 1939–1940, one such figure emerged: Simo Häyhä, a farmer of slight build and silent demeanor, who became the deadliest sniper the world has ever known.

Häyhä’s legend is not simply one of numbers, though his confirmed 542 kills in 98 days remain unmatched. It is a story of patience, adaptation, and a kind of understated heroism that transcends the battlefield. It is the story of a man who, armed with nothing but a standard rifle and a lifetime of hunting experience, terrified an invading army and became a myth among both friend and foe.

II. The Road to War: A Farmer’s Preparation

Simo Häyhä was born on December 17th, 1905, in the rural village of Rautjärvi, Finland, near the Russian border. His family owned a modest farm, raising rye, potatoes, hay, cattle, and pigs. Life was isolated, marked by hard work and self-reliance. At age 14, Simo left school to work the land full-time, but his true passion lay in the forests that surrounded his home.

From the age of 12, Häyhä was a hunter. Finland’s forests were thick with pine, spruce, and birch, home to elk, deer, fox, wolf, and bear. Hunting was not just a pastime—it was survival. It required patience, stealth, an understanding of terrain, and precise marksmanship. By age 20, Simo was known as the best hunter in his region. He could shoot a running fox at 400 meters. He could remain motionless in sub-zero temperatures for hours, waiting for the perfect shot.

In 1925, Häyhä completed his mandatory military service. The Finnish Civil Guard, a volunteer defense organization, trained him in marksmanship—a skill highly valued in Finnish military doctrine. Häyhä excelled, consistently hitting targets at 150, 300, and 500 meters with iron sights. He won multiple national shooting competitions, always using the same rifle: a Finnish-modified Mosin-Nagant M28-30, the weapon that would become legendary.

III. The Winter War: Finland Against the Giant

On November 30th, 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland. Stalin demanded territory; Finland refused. The Red Army crossed the border with one million soldiers, 3,000 tanks, and 2,500 aircraft. Finland’s military numbered only 300,000, with no tanks and just over 100 aircraft. The world expected Finland to surrender in two weeks.

Instead, Finland fought.

Häyhä was mobilized to the 6th Company of the 34th Infantry Regiment, deployed to the Kollaa River sector—just 50 kilometers from his farm. The terrain was dense forest, frozen and hostile. The mission was simple: stop the Soviets, kill anyone crossing the river, hold the line.

The Soviets attacked in waves, using overwhelming numbers and accepting massive casualties. On December 7th, 1939, 14,000 Soviet soldiers attacked 4,000 Finnish defenders. Finnish machine guns cut down wave after wave; by nightfall, 2,400 Soviets were dead, at a cost of just 68 Finnish casualties. The Soviets had tanks and artillery; the Finns had rifles, knowledge of the land, and a determination born of desperation.

IV. Becoming the White Death

Häyhä participated in the first battles as a standard rifleman, but he quickly noticed the predictability of Soviet tactics. They moved in groups, followed roads, exposed themselves. His hunting instincts told him that predictable prey dies easily.

On December 9th, 1939, Häyhä requested transfer to sniper duty. He was assigned as a designated marksman, operating independently, selecting his own positions, and engaging targets of opportunity. His only restriction: stay within 500 meters of Finnish lines.

Häyhä’s approach was methodical. He left Finnish lines before dawn, moved 200–400 meters toward Soviet positions, and found concealment in snowdrifts, fallen trees, or dense brush. He prepared each position meticulously, packing snow around himself to minimize disturbance from muzzle blast, exposing only his rifle barrel and head. He waited—sometimes for hours, motionless in temperatures below –40°C.

He preferred firing at 250 meters, where his 7.62x54mmR cartridge retained lethal energy and wind drift was minimal. He always aimed center mass, ensuring instant kills. His technique was consistent: fire once, observe, fire again if targets presented, never more than three shots per position before relocating. This discipline made him nearly impossible to find.

V. Invisible and Unmatched

By December 22nd, 1939, Häyhä had 87 confirmed kills. His company commander verified each one, matching Soviet casualties to Häyhä’s reports. The Soviets began to notice. Patrols found dead soldiers with single gunshot wounds, no sign of the shooter. Survivors reported hearing one shot, seeing one man fall, then another, but never seeing the sniper. The Soviets called him “Belaya Smert”—White Death.

Counter-sniper teams were deployed, equipped with scoped rifles and trained in standard tactics: observe for muzzle flash, return fire immediately. But Häyhä’s muzzle blast dissipated into snow, and he fired from deep concealment. He held snow in his mouth to prevent breath vapor from revealing his position. He was always gone before return fire arrived.

Artillery was tried next. On January 15th, 1940, Soviet guns bombarded suspected areas with 200 shells. Häyhä simply moved before the shells landed, surviving every attempt.

Infiltration teams tried to ambush him. On January 22nd, 1940, an eight-man Soviet team waited for him at a trail intersection. Häyhä sensed danger, circled around, and eliminated four of the ambushers before the rest fled.

VI. The Mathematics of Death

By February 1st, 1940, Häyhä had 219 confirmed kills. He averaged 4.7 kills per day, seven times more effective than the average sniper. As the winter deepened, Soviet uniforms became more visible against the snow, and Häyhä increased his operating range to 350–450 meters, compensating for greater bullet drop and wind drift with instinctive skill.

On February 17th, 1940, Häyhä killed 16 Soviet soldiers in one day, including a 12-man patrol eliminated in four minutes. His efficiency was staggering. By February 21st, his kill count stood at 387.

The Soviets responded by saturating the entire area with artillery—4 hours per day, 500 shells per day, for 12 days. They destroyed three square kilometers of forest, hoping to eliminate cover and make sniping impossible. Häyhä adapted, operating at dawn and dusk, reducing exposure time, firing fewer rounds per position. His kill rate dropped, but remained significant.

VII. The Wound and Survival

On March 6th, 1940, Häyhä’s luck nearly ran out. A Soviet patrol, hunting snipers, spotted a disturbance in the snow and fired a volley at his position. A bullet struck Häyhä’s face, shattering his jaw and severing his tongue. Blood filled his mouth and throat; he was choking, dying.

But survival was another skill Häyhä had mastered. He crawled 290 meters to Finnish lines, pursued by Soviet soldiers. Finnish machine gunners opened fire, suppressing the patrol, and medics performed an emergency tracheotomy to save his life. He was evacuated, operated on for six hours, and survived, though his face would be permanently disfigured.

One week later, the Winter War ended. Finland lost 11% of its territory, including Häyhä’s family farm, but survived as an independent nation. The cost was high: 70,000 Finnish casualties, but 321,000 Soviet casualties—an exchange ratio of 5:1.

VIII. Legacy: The Humble Hero

Häyhä spent months recovering in hospital, undergoing multiple surgeries to reconstruct his jaw. He was promoted to second lieutenant and awarded the Cross of Kollaa, Finland’s highest military decoration. When asked by Commander-in-Chief Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim how he became such a good shot, Häyhä replied with characteristic understatement: “Practice.”

Unable to return to his farm, now Soviet territory, Häyhä relocated with his family to a new farm provided by the Finnish government. He lived quietly, hunting, farming, and teaching marksmanship to new snipers. His methods—simplicity, patience, iron sights, breath control—became the foundation for Finnish sniper doctrine.

He never boasted about his kills. When journalists asked, he said, “I did what was necessary, nothing more.” When asked about heroism, he replied, “Heroes are men who sacrificed themselves. I survived. I’m just a farmer who learned to shoot.”

![Historical Badasses: Simo Häyhä – [DOOR FLIES OPEN]](https://doorfliesopen.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/simo-hayha.jpg)

IX. Reflection: The Cost of War

Häyhä understood the human cost of his actions. In a rare interview in 1998, he said, “I regret that the war happened. I regret that men died, but I don’t regret my actions. Soviet soldiers invaded my country. They would have killed Finns. I stopped them. That was my duty.”

He did not hate his enemies. He saw sniping as problem-solving, not combat. “I killed soldiers. They would have killed me if they had seen me first. That is war. It is not heroic. It is not glorious. It is killing. I was good at killing. That doesn’t make me proud. It makes me sad that I was needed.”

This humility, this psychological distance, was key to his effectiveness. He approached war as he approached hunting: with patience, discipline, and a focus on the task at hand.

X. Lessons for History

Modern military analysts attribute Häyhä’s success to five factors: exceptional marksmanship, intimate terrain knowledge, extreme weather, Soviet tactical incompetence, and luck. Remove any one factor, and his effectiveness would have decreased. His story demonstrates that technology is not everything—iron sights and discipline can outperform scopes and teams if fundamentals are sound.

Häyhä also embodied the Finnish concept of sisu—determination, perseverance, refusal to quit despite impossible odds. Shot in the face, he crawled to safety, recovered, and lived 62 more years. Sisu is not just surviving; it is refusing to be defeated by war, injury, or circumstance.

XI. The Rifle and Remembrance

Häyhä’s Mosin-Nagant M28-30 survived the war, used by other snipers and eventually retired to the Finnish Military Museum in Helsinki. It remains unremarkable in appearance—standard wood stock, iron sights, no modifications. Its legacy is in the hands that wielded it.

Today, Häyhä’s techniques are taught in sniper schools worldwide. His lessons—patience, simplicity, adaptation—are timeless.

XII. Conclusion: A Farmer’s Duty

Simo Häyhä died on April 1st, 2002, at age 96, in a veteran’s nursing home in Finland. His funeral was attended by hundreds—veterans, politicians, journalists. His grave is simple, marked only with his name, birth and death dates, and one word: soldier.

Häyhä would not want to be remembered as a hero, but as a farmer who did his duty. His 542 kills are statistics; the important thing is that Finland survived. That was enough for him. That should be enough for history.

In the end, the legend of the White Death is not just about killing. It is about the power of patience, the value of skill, and the quiet determination of a man who refused to be defeated. It is a reminder that sometimes, the fate of nations rests not in the hands of generals, but in the steady aim of a farmer lying silent in the snow.