“The Strongest Prison is Made of Lies”: How Canada’s “Open” Camps and 3,000-Calorie Meals Defeated the Nazi Ideology

LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA — In June 1940, Franz Weber stood at the edge of a Canadian prairie, waiting to be shot. He was a soldier of the Third Reich, a man raised on the thunderous speeches of Adolf Hitler and the terrifying warnings of his commanding officers. He had been told that capture meant death—or worse. He had been told that the Allies were weak, cruel, and barbaric.

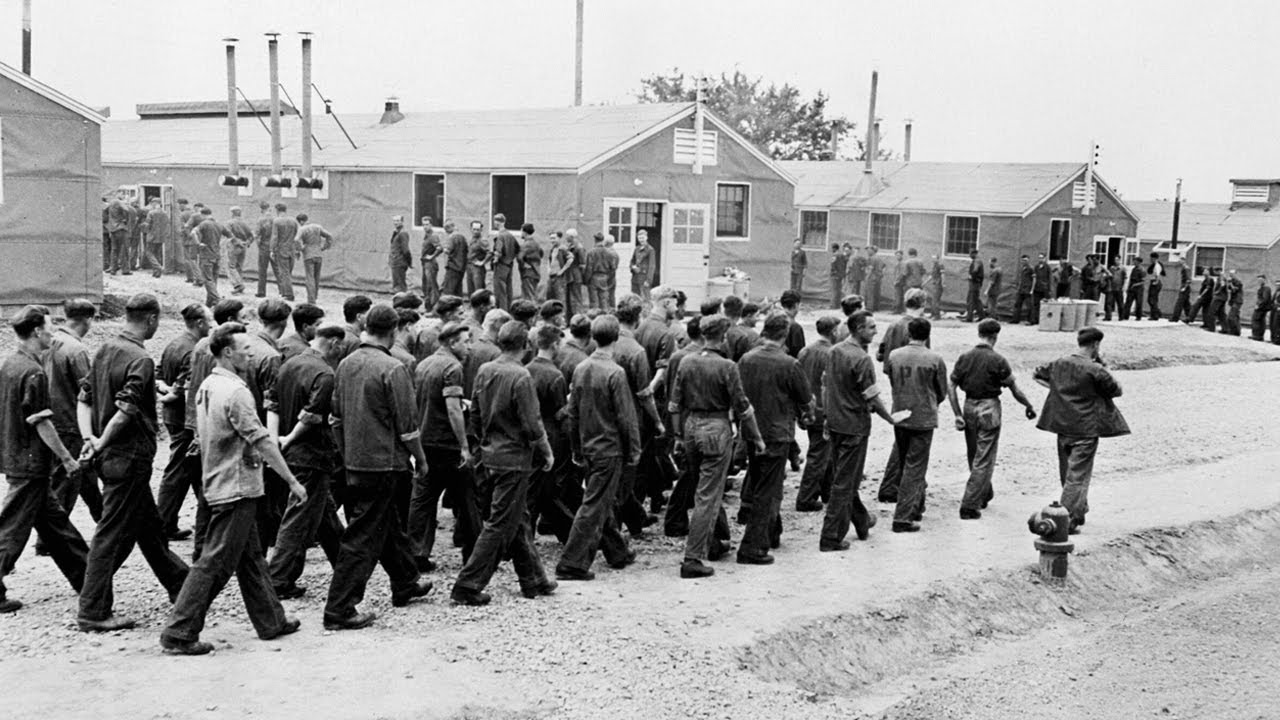

So, when he arrived at the prisoner of war camp in Lethbridge, Alberta, he looked for the walls. He looked for the machine gun towers. He looked for the barbed wire that would cage him in.

He saw nothing.

There were just wooden buildings arranged in neat rows and miles of green grass rippling in the wind. Confused and terrified, thinking this was a psychological game before the execution, Franz turned to a Canadian guard and asked where the fence was.

The guard looked at him, bored, and delivered a line that would haunt Franz for the rest of his life: “You can go for a walk if you want. Just be back by dinner.”

It wasn’t a trap. It was geography. They were thousands of miles from Germany, surrounded by an endless wilderness. But for Franz, that moment was the first crack in a worldview that had been carefully constructed by lies. Over the next six years, he would discover that the most effective weapon against hate wasn’t violence—it was a plate of bacon and eggs, a warm wool scarf, and the undeniable truth of a society so strong it didn’t need to lock its enemies behind a wall.

The Shock of Abundance

Franz’s journey to Canada had begun with dread. Captured in France, he was shipped across the Atlantic, expecting to be dumped in a frozen wasteland. Nazi propaganda had painted Canada as a primitive colonial outpost where prisoners would be left to freeze.

Instead, he watched from a train window as a massive, modernized country rolled by. He saw factories pumping smoke, roads filled with cars, and farms bursting with crops. Germany had claimed to be the greatest nation on earth, yet here was a country that seemed to function effortlessly on a scale he couldn’t comprehend.

The real psychological blow, however, was breakfast.

At 6:00 AM on his first morning, Franz shuffled into the mess hall, bracing himself for stale bread and watery gruel. The smell hit him first—the savory, impossible scent of frying meat.

A Canadian cook slapped a plate onto his tray: three strips of crispy bacon, scrambled eggs, toast with squares of real butter, and coffee with white sugar.

Franz stared at the food. His hands shook. This was a meal fit for a general in Berlin, and they were giving it to a low-ranking prisoner. He ate until his stomach hurt, surrounded by hundreds of other German soldiers doing the same. They ate in silence, some with tears in their eyes.

“We were told we would starve,” Franz later recalled. “Instead, we were eating 3,000 calories a day.”

The Christmas Truce of 1943

Life in the camp fell into a surreal rhythm. The prisoners worked on local farms, where they were treated like hired hands and paid 50 cents a day. They formed soccer leagues, organized theater troupes, and were given medical care that rivaled the best hospitals in Europe. When a prisoner named Josef had a toothache, he wasn’t told to suffer; he was taken to a dentist with shiny, modern tools who fixed him for free.

But the final blow to Franz’s indoctrination came in the winter of 1943.

It was Christmas Eve. The Canadian guards had decorated the mess hall with paper chains and a small tree. The air smelled of pine and roasted turkey. Dinner was a feast—ham, turkey, potatoes, gravy, and even beer.

After the meal, the doors opened, and a group of civilians walked in. They were townspeople from Lethbridge—mothers, fathers, and children. They didn’t carry weapons; they carried gifts.

An elderly woman with gray hair stopped at Franz’s table. She handed him a package wrapped in brown paper. “Merry Christmas,” she said.

Inside was a dark blue wool scarf. It was handmade. Franz ran his thumb over the tight, even stitches. This woman didn’t know him. He was the enemy. His countrymen were killing her countrymen across the ocean. Yet, she had spent hours knitting something to keep him warm.

Then, the singing started. A German prisoner began “Silent Night” in his native tongue. Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht. The Canadian guards joined in, singing in English. For a few minutes, two warring nations shared the same melody in the middle of the Alberta snow.

Franz looked around the room—at the full plates, the warm stove, the kind faces of the locals—and realized the truth.

“These people didn’t hate me,” he realized. “They pitied me. They knew I had been lied to. They showed me what a real country looks like—a country so strong it can afford to be kind.”

The Bitter Return

The war ended in May 1945, but it wasn’t until 1946 that Franz was sent home. He stood on the dock in Halifax, carrying a bag filled with English textbooks, photos of the camp, and his blue scarf. He was leaving the best years of his life behind.

When he arrived in Hamburg, the contrast was physically painful. The city was a graveyard of rubble. People walked the streets like ghosts, hollow-eyed and desperate.

Franz walked for three days to find his mother. When she opened the door, she screamed. She looked twenty years older, her hair white and her frame skeletal. Franz, meanwhile, was healthy, tanned, and 30 pounds heavier than when he had left.

She offered him tea made from dried roots and half her daily ration of bread—a hard, dark crust. Franz looked at the bread, then at his mother, and felt a crushing guilt. He had eaten steak and pie while she had starved.

The neighbors were less forgiving. “You got fat while we died,” one told him. “You were safe while we were bombed.”

Franz tried to explain about the camp, the lack of fences, the Christmas dinner. They looked at him like he was insane. The truth was too painful to accept: the enemy had treated their soldiers better than their own leaders had treated their citizens.

A Legacy of Peace

Franz stayed in Germany to help rebuild, using the farming skills he had learned in Alberta. But he never forgot Canada. He kept the blue scarf in a drawer, taking it out on hard days to remind himself that kindness was real.

He wasn’t the only one. In 1948, when Canada opened its doors to immigration, over 6,000 former German POWs made the shocking decision to move back to the country that had imprisoned them. They realized that Canada hadn’t been their prison; it had been their school.

Franz told his grandchildren the story until his death in 1984. He wanted them to know that the strongest prison isn’t made of wire or walls—it’s made of the lies you believe about the world.

“Canada won the war before they ever fought us,” he would say. “They defeated us not by breaking our bodies, but by showing us what we could have been.”