They Mocked His “Useless” Tunnel—Until a Deadly Blizzard Proved Everyone Wrong

In the late 1800s, up in the mountains where the ridge lines cut hard against the sky and winter arrived like a sentence, a man did something that looked so foolish his neighbors couldn’t stop talking about it.

Not because it was dangerous. Not because it was violent. Not even because it was ambitious in the way people admire.

It was foolish because it seemed pointless.

Late autumn had settled in—one of those seasons where the air starts to smell like iron and every brittle leaf on the ground feels like a warning. Most homesteaders in that era used the same rituals their fathers and grandfathers had used: reinforce the roof, patch the cabin seams, dig storm cellars, stack firewood against the house under the eaves. They trusted tradition, because tradition had kept people alive long enough to become tradition.

But this man, isolated on a ridge above the valley, spent his precious days doing something else.

He built a long tunnel out of scrap canvas and rough timber poles—low to the ground, narrow, stretching from his woodshed all the way to his front door. It wasn’t a tent. It wasn’t a barn. It wasn’t big enough to store animals. It looked like a giant fabric snake slithering through the yard, flapping in the wind like a joke made physical.

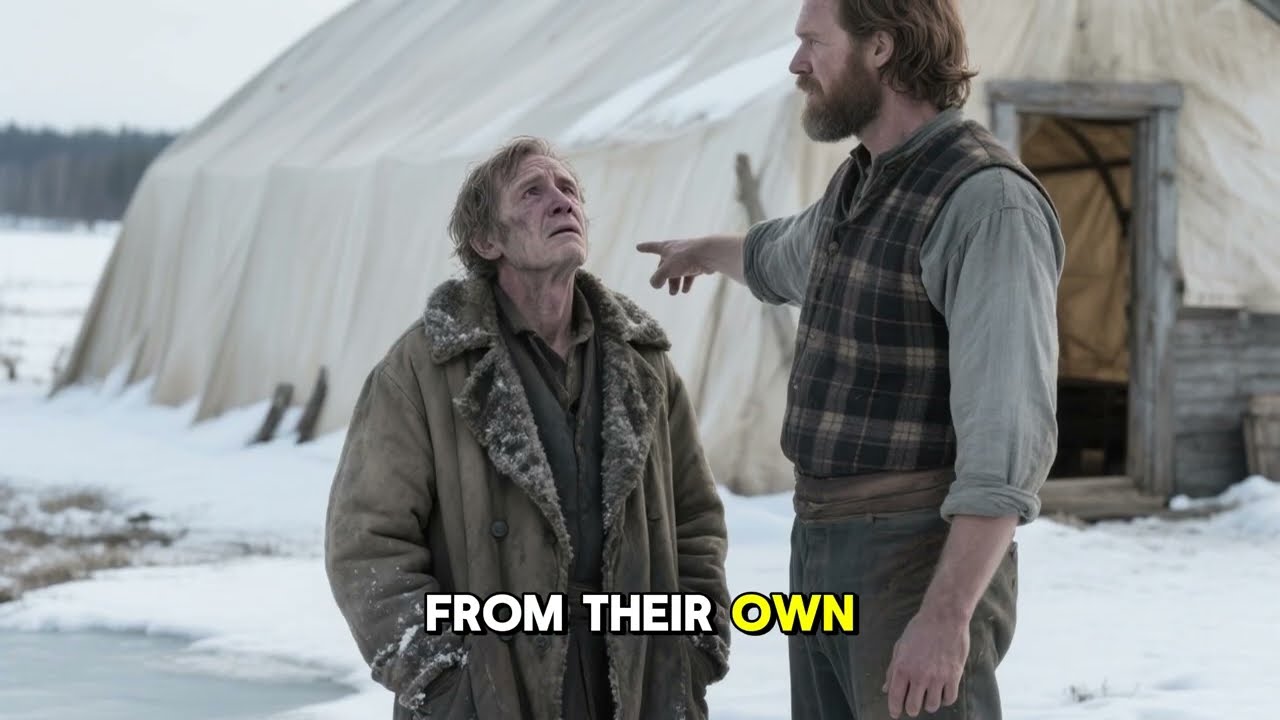

People in the nearby settlement laughed at him openly. Resources were scarce. A piece of sturdy canvas could patch a drafty window. It could cover a leaking roof. Timber poles could brace a weak wall. Using them to build a covered walkway felt like stupidity dressed up as creativity.

As they rode past on horses, shivering in coats, they pointed and made up names for what he was doing—ghost walkway, fool’s tunnel, fabric toy. They said the isolation had finally gotten to him.

The man never defended himself. He didn’t argue. He didn’t explain. He just kept tying knots, driving stakes into freezing mud, pulling the canvas tight enough to shed water but loose enough to breathe.

He wasn’t stubborn for no reason.

He knew something the others didn’t.

And when the blizzard hit, his neighbors discovered the terrifying difference between tradition and understanding.

The real killer wasn’t the cold—it was water

In frontier winters, firewood wasn’t just comfort. It was life support.

Firewood meant heat. Cooking. Light. The ability to melt snow for drinking water. It was the difference between living long enough to see spring and becoming another silent story buried under drifts.

Most homesteaders protected their wood the way they’d been taught: stack it against the cabin wall, under the eaves, believing the heat from inside the cabin would keep the logs dry. It seemed logical. It was also a trap, especially in mountain valleys where wind didn’t move in clean straight lines.

The man on the ridge understood an invisible enemy: moisture.

He understood that deep snow doesn’t just sit politely on the ground. Wind swirls, eddies, and drives powder snow into cracks and crevices—especially into wood piles stacked close to a warm cabin wall. During the day, sunlight or escaping heat melts that fine snow, turning it into seepage that soaks into logs. At night, temperatures plunge, and that water refreezes into a solid glaze.

The result is not just damp wood.

The result is wood that becomes a monolith—logs fused together in ice, impossible to separate, impossible to light, useless when you need it most.

That’s why the tunnel mattered.

It wasn’t a convenience. It wasn’t a luxury. It wasn’t a strange hobby.

It was survival engineering.

A ridiculous tunnel with a brutal purpose

The man’s neighbors saw a covered walkway. He saw a transition zone.

He understood that the deadliest winters don’t always kill by temperature alone. They kill by exhaustion—by forcing you to fight the elements for every basic task until you burn through your energy, your supplies, and your will.

His tunnel created a controlled space between the outside storm and the inside cabin. A buffer. A microclimate. A place where the air was still cold but stable, dry, and protected from wind-driven snow.

It wasn’t meant to be comfortable. It was meant to be predictable.

He built it before the heavy clouds rolled over the peaks, before the valley fell into that strange stillness that feels like a predator holding its breath. As the sky darkened and the world turned monochrome—white and gray and warning—the laughter in the settlement faded.

Because even the people who mocked him could sense something coming.

The air grew heavy. The silence sharpened. The kind of quiet that doesn’t feel peaceful—only loaded.

The man finished his last tie-down, looked at the sky, and went inside.

And the storm arrived.

The blizzard that didn’t “arrive”—it attacked

When the blizzard hit, it didn’t drift in gently. It slammed into the mountain like a freight train made of ice.

In less than 48 hours, five feet of snow buried the valley. Wind howled so hard it turned breath into pain. Drifts formed against doors, windows, walls—anything that gave the storm something to lean on.

For the neighbors who had mocked the tunnel, the reality of winter survival snapped into focus the moment they tried to fetch firewood.

They opened their doors and found walls of white blocking the way. They shoveled frantically, carving paths that filled in again, pushing forward with the kind of panic that burns calories faster than it solves problems.

Eventually they reached their wood piles—stacked neatly against the house like always.

And there, they found disaster.

Heat escaping through poorly insulated cabin walls had warmed the snow resting on the wood. During the day, it melted. At night, the brutal cold froze the runoff instantly. Their wood piles became solid blocks of ice—logs fused together, inseparable, as if welded by winter itself.

Men stood in blinding wind hacking at their own fuel supplies with axes, risking frostbite and collapse to pry a single log loose. When they managed to free one, it was soaked through with frozen moisture. In the stove, it hissed and popped, refusing to burn hot.

This is the cruel physics of wet firewood: energy that should heat a room gets wasted boiling water out of the logs. The fire doesn’t roar—it struggles. The stove doesn’t warm the cabin—it fights to stay alive. The colder it gets, the more wood you burn, but the less heat you receive.

That’s how winter kills even when there is “plenty” of wood nearby.

Inside those cabins, temperatures dropped. Children were wrapped in every blanket the family owned, huddled in the center of the room like animals seeking shared heat. Fathers cursed the weather, cursed the mountain, cursed fate—never fully realizing the failure had been sealed weeks earlier when they chose tradition over adaptation.

They weren’t losing to the storm alone.

They were losing to moisture.

Up on the ridge: the “madman” walks calmly through his tunnel

While the valley fought for every log, the ridge held a different scene—so different it almost feels insulting.

The man opened his front door and stepped not into the biting gale, but into the dim, canvas-filtered light of his tunnel.

Yes, the structure shook violently in the wind. The fabric snapped and flapped with deafening force. But inside, the ground was dry, clear of snow, protected.

He walked in his shirt sleeves, not needing a heavy coat, down the length of the tunnel to his woodshed.

The air in the woodshed was cold—but perfectly dry.

That was the genius.

The tunnel acted as a thermal buffer: neither fully inside nor fully outside. It prevented the harsh temperature clashes that cause condensation and icing. It also removed the storm’s ability to sabotage him with wind-driven snow. The wind slid over the rounded canvas shape, unable to find a flat face to push against or corners to pack with drifts.

He didn’t have to battle nature just to reach fuel.

So he burned only what he needed.

While neighbors burned through winter stores at double the rate trying to dry wet logs and keep a weak fire alive, he conserved energy and wood because his wood stayed bone dry.

He carried armfuls of hickory back to his stove. The logs caught instantly, throwing deep penetrating heat that dried the air and warmed the body all the way to the bones.

Outside, the blizzard howled—a sound that usually signals a fight for life.

For him, it was just noise on the other side of canvas.

The tunnel didn’t just protect his wood.

It protected his strength.

And in winter survival, strength is everything.

The real difference was foresight, not toughness

It’s easy to romanticize frontier life as a contest of grit. We tell stories about tough men, hard women, and stubborn families who survived on willpower alone.

But this story exposes a different truth: survival isn’t won by toughness. It’s won by understanding.

The man didn’t survive because he was stronger than his neighbors. He survived because he saw the problem before it arrived.

He recognized that winter wasn’t only cold. Winter was wet, and wind, and physics, and exhaustion.

And he built a solution that looked silly to people who didn’t understand the threat.

That’s one of the hardest lessons of any harsh environment: the biggest dangers are often invisible until it’s too late.

Weeks pass, and a new fear appears

As the storm dragged on for weeks, another danger emerged: scarcity.

Surviving the first night is one thing. Surviving the entire season is another. Food stores shrink. Fatigue accumulates. Small injuries become dangerous. Cabin walls sweat moisture into bedding. Smoke from wet wood irritates lungs until coughs turn chronic.

The transcript hints at this slow grind, the way winter becomes less about dramatic moments and more about endurance.

And endurance is where most people break—not because a single event kills them, but because a thousand small struggles wear them down.

For the valley homesteaders, the tunnel wasn’t just a clever trick.

It was the dividing line between living and slowly being consumed.

Spring thaw: the truth becomes visible

When spring finally arrived, it didn’t come gently. It came like a release valve.

Snow melted into slush. Valleys turned into mud pits. Creeks swelled with runoff. The world shifted from white prison to wet chaos.

And in that thaw, the true cost of winter became visible.

The neighbors emerged from their cabins gaunt and half-white, faces gray from months of inhaling smoke from wet wood and shivering through nights when the fire offered no real comfort. Their wood piles were wrecked—half-rotted from freeze-thaw cycles. Many had been forced to burn furniture, shelves, even floorboards just to make it through the final brutal weeks of February.

They climbed the ridge to check on the man they’d mocked, expecting to find a frozen corpse or a broken recluse.

If they had suffered that much using conventional methods, surely his ridiculous contraption had doomed him.

What they found stopped them cold.

The man was sitting on his porch shaving with a steady hand, looking as healthy and strong as he had in the autumn.

The tunnel was gone now—canvas folded neatly away for next year.

But evidence of its success was everywhere. While their yards were mud pits, the ground where the tunnel had stood was dry and packed hard. His remaining wood pile was pristine—logs curing perfectly in spring air instead of rotting.

The neighbors asked him how he had managed to keep his house so warm that he didn’t even look tired.

He didn’t gloat. He didn’t shame them.

He simply pointed to the folded canvas and explained.

A microclimate built from humility

The tunnel, he told them, hadn’t just kept snow off.

It used the earth’s own small amount of radiant heat to keep the air inside a few degrees warmer than outside. That tiny difference mattered. It created a microclimate that reduced condensation and prevented icing. It stabilized temperature swings. It offered protection from wind-driven snow. It kept the ground dry.

He didn’t survive by fighting nature head-on.

He survived by working around nature.

And that required something many people mistake for weakness: humility.

The man understood that fighting nature is usually a losing battle. Nature doesn’t get tired. It doesn’t get emotional. It doesn’t care if you’re brave.

But if you respect nature’s rules and design around them, you can survive without wasting your strength.

That’s why the neighbors, who had laughed at him in autumn, were now measuring the distance from their own doors to their sheds, planning their own tunnels for next winter.

From “madness” to passive design

The story of the canvas tunnel spread quietly through the mountains—not as a legend of magic, but as a practical lesson. Today, we might call it passive design: using simple materials and smart positioning to control environment without burning extra energy.

We live now with central heating, insulated jackets, weather apps, and modern building materials. It’s easy to forget what mattered most for most of human history.

Staying dry.

Dry fuel. Dry clothes. Dry bedding. Dry air.

Moisture is the silent assassin. Cold you can prepare for with layers and fire. Moisture turns everything against you: it freezes your fuel, chills your clothes, rots your supplies, and slowly steals your heat.

A piece of canvas on some poles doesn’t look heroic.

But in the frontier world, it could be the difference between seeing spring flowers and becoming part of frozen history.

The deeper lesson: the courage to look foolish

This story isn’t only about a tunnel. It’s about social instinct—and how dangerous it can be.

Communities often punish difference. When someone does something new, the first response is laughter. Not always because people are cruel, but because mockery is easier than admitting uncertainty. If you laugh at the unfamiliar, you don’t have to confront the possibility that your own methods might fail.

The man on the ridge didn’t survive because he won an argument.

He survived because he was willing to look foolish while he quietly built the thing that saved his life.

That willingness is rare. And it matters far beyond winter survival.

Because in every era, in every community, there are people building “useless” things—ideas, systems, inventions, habits—that others dismiss because they don’t yet understand the problem those things are meant to solve.

Sometimes those people are wrong.

But sometimes they’re building a tunnel while everyone else is still stacking wood in the rain.

What would you have done?

If you had ridden past his cabin in late autumn, watching the canvas flap and the poles lean, would you have laughed?

Would you have called him a madman?

Or would you have stopped, looked closer, and asked what he knew that you didn’t?

That question is the real spine of this story. Not the blizzard. Not the tunnel. Not the neighbors freezing in cabins.

The question is whether you can recognize preparedness when it looks strange.

Because the world doesn’t always warn you politely before it changes. Sometimes disaster arrives like a freight train of ice. Sometimes the storm exposes every weak assumption you’ve been leaning on.

And when that happens, the “useless” tunnel stops being a joke.

It becomes the only thing between you and the cold.

The man on the ridge proved something the frontier learned again and again: the greatest survival tool isn’t something you buy. It’s the ability to anticipate reality, even when it makes you unpopular.

In the end, the neighbors didn’t just learn how to build a tunnel.

They learned the cost of laughing at what they didn’t understand.

And they learned it the hard way—one frozen log at a time.