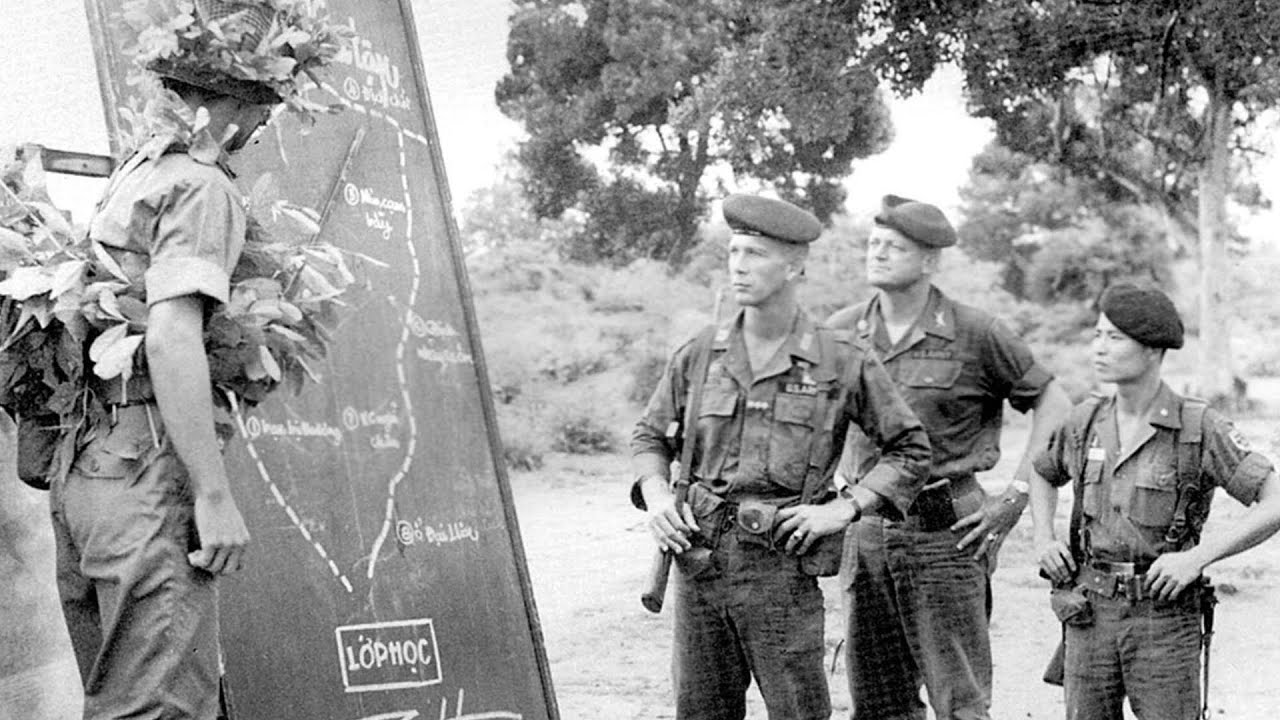

1967, a classified briefing room in Vietnam. 12 American Green Berets, the most elite soldiers the United States had to offer, receive an order that makes absolutely no sense. Under no circumstances are they to follow Australian SAS patrols. Not literally, not figuratively, not ever.

Wait, what? The Americans are forbidden from learning from a handful of Australians who smell like rotting fish and move through the jungle like ghosts. These are Green Berets we’re talking about. The best of the best. And they’re being told to stay away from the Aussies like they’re radioactive. But here’s the thing. This wasn’t an insult.

This was a survival order because anyone who followed an Australian patrol walked straight into a killing zone. And the Pentagon buried this story for 40 years because the truth was simply too embarrassing to admit. 500 Australian SAS soldiers achieved kill ratios that half a million Americans couldn’t match. 500 to1.

Some reports say 700 to1. Numbers so impossible that American commanders refused to believe their own intelligence reports. How did they do it? What was the spiderweb ambush that made the Vietkong call them ma run, jungle ghosts? And why did the Pentagon classify everything these men discovered about winning in the jungle? Stay with me until the end because what you’re about to learn was hidden in classified archives for decades.

And once you know the truth, you’ll understand why American generals still don’t like talking about it. This is the forbidden story of the Australian SAS in Vietnam, Fuakui Province, 1967. A classified briefing room at Long Bin Base. 12 American Green Berets sat in stunned silence as their commanding officer delivered an order that defied everything they had learned at Fort Bragg.

The words hung in the humid air like a death sentence for their professional pride. Under no circumstances were they to follow in the footsteps of Australian SAS patrols. Not literally, not figuratively, not ever. The Americans exchanged confused glances. These were elite soldiers, graduates of the most demanding special operations training the United States military could devise.

They had been taught they were the best in the world. And now they were being told to stay away from a handful of sunburned Australians who smelled like rotting fish sauce and moved through the jungle like something not entirely human. But this was no insult. This was survival advice of the highest order.

And the reason behind it would shake everything these green berets thought they knew about warfare. What those Green Berets did not yet understand would take months of painful observation to grasp. The Australians operated by rules that seemed to come from another century, another species, another dimension of warfare entirely. And the jungle paths they walked were not paths at all.

They were killing grounds disguised as safe passage. To follow an Australian SAS patrol was to volunteer for a body bag. The order had come directly from Military Assistance Command Vietnam. And behind it lay a story of tactical genius so profound that the Pentagon would spend the next four decades trying to pretend it never happened. This is that story.

And what you are about to learn was buried in classified archives until long after the war ended. But the classified files were only the beginning of the mystery. The Australian Special Air Service Regiment had arrived in Vietnam with a reputation built on Borneo, on Malaya, on conflicts the American public had never heard of.

They numbered barely 500 men across the entire war. A statistical irrelevance compared to the half million American troops who would eventually flood the country. But statistics, as the Vietkong would learn, can be deceiving in the most fatal ways imaginable. The first American intelligence officer to study their methods was a young captain named Marcus Webb.

Assigned to lies with the Australians at their base in New Webb had graduated top of his class at West Point. He had completed Ranger School with honors. He believed, as most Americans did, that the key to winning in Vietnam was superior firepower, helicopter mobility, and overwhelming technological advantage.

His first week with the Australians shattered every assumption he had ever held about warfare. Yet the real shock was still waiting for him in the jungle. The Australians did not call in air strikes when they found enemy positions. They did not radio for helicopter extraction at the first sign of contact. They did not carry enough ammunition to sustain a prolonged firefight.

And they absolutely categorically refused to use the trails that American patrols considered standard operating procedure. Webb watched a five-man Australian patrol prepare for deployment and thought he was witnessing professional incompetence. The men had stopped bathing three days before the mission. They had stopped using soap, toothpaste, and insect repellent.

They rire of newokm, the fermented fish sauce that Vietnamese peasants used in every meal. Their uniforms were deliberately torn and stained. Their boot souls had been modified with cuts that made their footprints unrecognizable. This was not slovenliness. This was the smell doctrine. And it would prove more valuable than a thousand artillery batteries.

But the smell doctrine was merely the outer layer of something far more lethal. The real secret lay in how they moved. American patrols traveled fast and loud, covering maximum ground in minimum time. They used established trails because trails were easier. They moved in daylight because daylight was safer. They made noise because making noise scared the enemy away.

Or so the theory went. The Australians inverted every single one of these principles. They moved at night when possible, using darkness as their primary weapon. They traveled off trail exclusively, cutting through vegetation so dense that progress was measured in meters/ hour rather than kilome per day. They made no sound whatsoever.

Not a whisper, not a cough, not the snap of a single twig. And here was the critical detail that would eventually generate that forbidden order at long bin. When the Australians did use trails, they did so only to set ambushes. The paths they walked were not routes of travel. They were elaborate killing zones pre-arranged and memorized where every tree and every bush concealed a potential firing position.

To follow an Australian patrol was to walk directly into their backup ambush line. This was the trap that no American commander wanted to explain to grieving families back home. Webb discovered this truth the hard way during his third week in Fuaktui. He had requested permission to accompany an Australian patrol eager to learn their methods firsthand.

The patrol leader, a sergeant named Colin Mitchell, had refused. No Americans, no exceptions, no explanations given. Webb was furious. He was an intelligence officer with top secret clearance. He had authorization from MACV itself. Who were these colonials to refuse a direct liaison request? Mitchell looked at him with eyes that seemed to belong to a different species.

The sergeant had been in the jungle for four straight months with only brief returns to base. His skin had taken on a grayish tinge. His movements were economical to the point of being mechanical. When he finally spoke, his voice was barely above a whisper, as though loud speech had become physically impossible for him. What Mitchell said next would change Web’s understanding of warfare forever.

If you follow us, you will walk into our rear security ambush. We will not know you are American until after we have engaged. You will not survive the first 3 seconds. This is not a threat. This is mathematics. Web demanded clarification. Mitchell provided it with terrifying precision. The Australians operated a system they called the spiderweb.

Every patrol laid multiple ambush lines as they moved through terrain. These were not formal positions with claymore mines and trip wires, though those existed, too. These were mental markers, pre-selected kill zones where every member of the patrol knew exactly where to fire if contact occurred from any direction. The rear ambush was always the most lethal.

It was designed to eliminate anyone attempting to track the patrol. And the system had never failed. Not once. Enemy scouts, Vietkong trackers, curious civilians, and yes, well-meaning American allies who thought they could learn by following all would meet the same fate. The Australians did not check identification before engaging rear contacts. They could not afford to.

In the jungle, hesitation measured in micros secondsonds meant the difference between living and not living. Their doctrine was simple and absolute. Anything behind them was hostile. Anything behind them received immediate and overwhelming fire. Webb asked how many friendly forces had been lost to this system.

Mitchell’s answer was zero because nobody followed them because word had spread through the Vietkong network, through the North Vietnamese Army intelligence apparatus, and eventually through American command channels as well. The warning had become legend among those who fought in the jungle. Do not follow the Australians. Do not track the Australians.

Do not attempt to ambush the Australians from behind. The enemy called them Maung, jungle ghosts, phantoms who appeared from nowhere, struck with surgical precision, and vanished before reinforcements could respond. But that name contained more than superstitious fear. It contained hard-earned tactical respect from an enemy who had been fighting foreign invaders for 20 years.

The Vietkong had learned to track American patrols with relative ease. The noise signatures alone were sufficient. The smell of American soap, American cigarettes, American insect repellent carried for hundreds of meters through the humid air. The bootprints were distinctive and unaltered. The radio chatter was constant and predictable.

But the Australians left no trail that could be followed. And this invisibility was no accident. It came from teachers older than European civilization itself. Their boots had been modified by Aboriginal trackers who served as instructors at the SAS training facility in Western Australia. These men came from traditions that predated European settlement by 40,000 years.

They had spent their entire lives reading the earth the way Americans read newspapers, and they had taught the SAS soldiers how to become invisible on any terrain. The boot modifications were just the beginning. The Australians walked in single file with the rear man using a branch to obscure footprints as they moved.

They avoided soft ground whenever possible. They crossed streams at rocky points where water would erase their passage within seconds. They selected rest positions with multiple exit routes and never used the same site twice. Captain Web spent six months studying these methods. He filled 17 notebooks with observations, diagrams, and tactical analyses.

He submitted report after report to Macv headquarters, arguing that American forces should adopt Australian techniques across the board. His reports were classified, filed, and ignored. But the reasons for this institutional blindness were even more disturbing than the blindness itself. The American military establishment of 1967 was not prepared to admit that a force of 500 Australians operating in a single province had achieved tactical results that half a million Americans could not match.

The numbers were simply too embarrassing. By the end of the war, Australian SAS patrols would achieve a confirmed elimination ratio of somewhere between 500 to1 and 700 to1, depending on which classified assessment you believed. For every Australian SAS soldier who fell in action, between 500 and 700 enemy combatants were confirmed eliminated.

American forces, by contrast, operated at ratios closer to 10 to1. Highly effective by historical standards. utterly humiliating compared to the Australians. These figures were buried so deep that decades would pass before anyone outside classified circles learned the truth. These figures were not propaganda.

They were derived from body counts, prisoner interrogations, captured enemy documents, and signals intelligence. They were verified by multiple independent sources and they were immediately classified at the highest levels because their implications were too damaging to American military prestige. How had the Australians achieved the impossible? The answer lay not in superior weapons, superior training, or superior courage.

American special forces possessed all of these qualities in abundance. The answer lay in a fundamental philosophical difference about the nature of jungle warfare. Americans fought the jungle. Australians became the jungle. And that transformation required sacrifices that American doctrine could never accept.

This distinction sounds abstract, but its practical applications were devastatingly concrete. American doctrine emphasized speed, mobility, and firepower. Get in fast, hit hard, get out before the enemy could respond. This approach worked brilliantly in conventional warfare. In Vietnam, it produced an endless cycle of brief contacts, inconclusive engagements, and mounting casualties from ambushes that American patrols walked into with depressing regularity.

Australian doctrine emphasized patience, invisibility, and precision. Move slowly. See everything. engage only when victory is certain. This approach required skills that could not be taught in a six-week training course. It required a complete psychological transformation. The men who volunteered for Australian SAS selection underwent a process that American observers described as somewhere between monastic initiation and deliberate psychological breakdown.

The selection course had a failure rate exceeding 90%. Those who passed emerged as something different from ordinary soldiers. They could remain motionless for hours in positions that would have driven most men to madness. They could detect enemy presence through smell alone, identifying the tobacco and food signatures that Vietkong units carried.

They could navigate without compasses through terrain that GPS systems would struggle with decades later. But most importantly, they had internalized a patience that bordered on the inhuman. The spiderweb ambush was the ultimate expression of this patience, and one operation would prove its devastating effectiveness beyond any doubt.

The operation that demonstrated the full horror of the spiderweb took place in September 1966 in a patch of jungle that American intelligence had written off as low priority. Five Australian SAS soldiers established an ambush position along a trail that signals intelligence suggested was being used for enemy resupply.

They arrived at the position in darkness, moving so slowly that it took 6 hours to cover 400 m. They settled into their hides and began waiting. The wait lasted 43 hours. For nearly two full days, five men remained essentially motionless in the Vietnamese jungle. They did not speak. They did not eat anything that required movement to prepare.

They urinated in place using techniques designed to minimize scent and sound. They fought off insects through pure mental discipline rather than swatting or scratching. American observers who later reviewed the operation logs refused to believe the timeline was accurate. No soldiers could maintain tactical readiness for 43 hours without movement, without communication, without the basic physical activities that human bodies require.

But the Australians had done exactly that. And when the enemy finally came, the result was not a battle. It was an execution. A Vietkong resupply column of 26 personnel walked directly into the kill zone at 0300 hours on the third day. The Australians allowed the column to fully enter the ambush area. Then they opened fire simultaneously from five positions.

The engagement lasted 11 seconds. 23 enemy combatants were eliminated in the initial volley. The remaining three were wounded and subsequently captured after attempting to flee into secondary ambush positions that the Australians had prepared on the previous day. Zero Australian casualties, zero rounds wasted, zero enemy escape.

The mathematics of 11 seconds had rewritten the rules of jungle warfare. The captured prisoners were interrogated and provided intelligence that led to three subsequent operations, each equally devastating. Within one month, the entire enemy logistics network in that sector had been dismantled. Captain Webb was present for the afteraction briefing.

He watched the Australian patrol leader deliver his report in the same barely audible whisper that seemed to be standard for men who had spent too long in the jungle. The facts were presented without emotion, without pride, without any acknowledgement that something extraordinary had occurred. Webb asked how they had maintained focus for 43 hours.

The patrol leader looked at him as though the question made no sense. You wait until the enemy comes, however long that takes. That is the job. This simple answer contained a philosophy that American military doctrine could not accommodate. This was the fundamental difference that American doctrine could not accommodate. The Australians did not operate on schedules.

They did not have extraction windows, mandatory check-in times, or logistical constraints that forced them to move before their missions were complete. They carried enough food and water for 10 days minimum. They could extend that to 14 days if necessary by supplementing with jungle resources. American patrols, by contrast, rarely exceeded 72 hours in the field.

They were tied to helicopter schedules, artillery support windows, and a command structure that demanded constant communication. This made them predictable, and in jungle warfare, predictability was the first step toward a body bag. The Vietkong had learned American patterns within months of the first major deployments.

They knew when American patrols departed, how far they would travel, and when they would return. They could calculate with reasonable accuracy where American forces would be at any given time. The Australians offered no such patterns to exploit. Their unpredictability made them more terrifying than any weapon system the Americans possessed.

A five-man SAS patrol might remain stationary for 3 days, then move 30 km in a single night, then establish a new ambush position and wait for another week. There was no predictable behavior to observe, no schedule to exploit, no weakness in the operational tempo. Enemy commanders who attempted to track Australian movements found themselves chasing ghosts through terrain that seemed to swallow every search party they sent.

But there was a cost to this effectiveness that American observers rarely discussed in their reports. And this cost would haunt the men who paid it for the rest of their lives. The men who mastered these techniques were changed by them in ways that did not always facilitate return to normal society. Sergeant Mitchell, the patrol leader who had warned Webb about the rear ambush system, completed four consecutive tours in Vietnam.

He accumulated more confirmed eliminations than any other Australian soldier in the war. He was decorated repeatedly for actions that remained classified for decades. He also never slept more than two hours consecutively for the rest of his life. The hypervigilance that kept him alive in the jungle became a permanent neurological condition.

His brain had been rewired by years of existing in an environment where relaxation meant termination. He could no more turn off his tactical awareness than he could stop his heart from beating. Other veterans reported similar transformations. They had difficulty maintaining eye contact because their vision had been trained to constantly scan peripheries for movement.

They could not sit with their backs to doors. They woke instantly at any unexpected sound, often already in motion toward cover before conscious thought engaged. The jungle ghosts had brought the jungle home with them, and it would never let them go. Some found ways to channel these changes into productive civilian careers. Others did not.

The Australian government would eventually acknowledge that SAS veterans experienced psychological difficulties at rates far exceeding regular military personnel, though the full extent of these difficulties remained obscured by classification and institutional reluctance. This was the dark bargain that jungle warfare demanded.

Become the ghost, achieve impossible effectiveness, but lose something of your humanity in the process. The Americans who observed Australian methods understood this bargain intellectually. They wrote about it in their classified reports. They recommended that selected American units be trained in similar techniques with appropriate psychological support systems.

Those recommendations were rejected. And the reason for that rejection would cost more lives than any single battle of the war. The reason was not cruelty or indifference. It was mathematics of a different kind. The American military was fighting an industrial war with an industrial army. Half a million soldiers required standardized training, standardized doctrine, and standardized expectations.

Creating elite units that operated by completely different rules would have complicated command structures, logistic systems, and personnel management beyond what the existing bureaucracy could accommodate. Better to maintain the current approach, absorb the casualties, and hope that overwhelming firepower would eventually produce victory.

This decision would prove catastrophic, but its full consequences would not become apparent for years. Meanwhile, the Australians continued their ghost war in Fuaktui province. They continued racking up elimination ratios that American commanders refused to believe and tactical successes that Pentagon planners refused to study.

The order prohibiting American forces from following Australian patrols remained in effect until the last Australian combat units withdrew in 1971. By that point, the warning had become unnecessary. Every American soldier in Vietnam knew the reputation of the Maung. Every American commander understood that the Australians operated by rules that did not apply to anyone else.

Some American special operators did eventually learn the spiderweb technique, though not through official channels. They learned it from Australian veterans in bars and training exchanges during the decades that followed. They incorporated elements into their own doctrine, adapting the patience and precision approach for new environments and new enemies.

But those lessons came too late for the men who needed them most. By the time the United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001, American special operations forces had finally absorbed many of the lessons that Webb had documented in 1967. The small unit tactics, the extended patience operations, the emphasis on invisibility over firepower.

These methods saved countless American lives in the mountains and deserts of the Middle East. They would have saved many more lives if they had been adopted 34 years earlier. The price of institutional pride could now be measured in gravestones. Colonel David Hackworth, the most decorated American soldier of the Vietnam War, said it directly in an interview that was classified for two decades.

The Australians showed us how to win this war in 1966. We were too proud to listen and we paid for that pride with 58,000 names on a black wall in Washington. Hackworth had spent time with the Australian SAS during his multiple tours. He had seen their methods firsthand. He had tried to implement similar approaches in his own units with significant success.

And he had been systematically marginalized by a command structure that viewed his advocacy for Australian tactics as borderline insubordination. The records of his recommendations, his reports, and his increasingly frustrated communications with Pentagon leadership were sealed until 1996. When they were finally released, military historians discovered a paper trail of ignored warnings, rejected proposals, and institutional blindness that read like a tragedy in bureaucratic form.

Those files told the story of a war that could have ended differently. Hackworth had predicted the eventual outcome of the war with disturbing accuracy. He had explained exactly why American tactics were failing and exactly how Australian methods could reverse the trend. He had provided specific actionable recommendations supported by evidence from actual operations. None of it mattered.

The machine ground forward on its predetermined course, and the casualty lists grew longer with each passing month. The Australians were withdrawn from Vietnam, not because their mission was complete, but because political pressure at home had made continued involvement impossible. They left behind a province that was more pacified than any comparable area in the country.

They left behind enemy forces that had learned to fear the sound of silence more than the roar of American helicopters. They left behind lessons that would take a generation to learn. And they left behind ghosts that still haunt the jungle to this day. Today, the spiderweb ambush technique is taught at special operations schools around the world.

The smell doctrine has been adapted for environments from Middle Eastern deserts to African jungles. The patients operations that seemed impossible in 1967 are now standard practice for elite units facing asymmetric threats. But the original warning still echoes through military history. A reminder of what happens when institutional pride prevents learning from those who have mastered their craft. Do not step in their tracks.

Do not follow where they walk. The path of the jungle ghost is not for those who have not paid the price of transformation. The Vietkong learned this lesson in blood. The Pentagon learned it in archived reports that gathered dust for decades. And the Green Berets, who sat in that briefing room at Long Bin, learned it in the only way that truly matters.

They survived because they listened to an order that made no sense until it made all the sense in the world. The Maung are gone now, retired to suburbs and farms across Australia. Their war fading into history with each passing year. But their methods live on in doctrine manuals and training programs, in the muscle memory of operators who have never heard their names, but who move through darkness using techniques those men invented.

And somewhere in the classified archives of three nations, the full story remains sealed. Not because it contains military secrets that could endanger current operations, but because it contains truths that military establishments still find too uncomfortable to acknowledge. 500 men achieved what 500,000 could not.

And they did it by breaking every rule that modern warfare held sacred. That is the legacy of the Australian SAS in Vietnam. That is why American Green Berets were forbidden from following their patrols. And that is why even now, decades later, the men who were there speak of those jungle ghosts in whispers, as though speaking too loudly might summon them back from whatever shadows they now call home.

Some secrets are buried because they are dangerous. Others are buried because they are embarrassing. The story of the Maung is both. And now you know why that order was given in a classified briefing room in 1967. Do not step in their tracks because their tracks lead to places that change you forever.