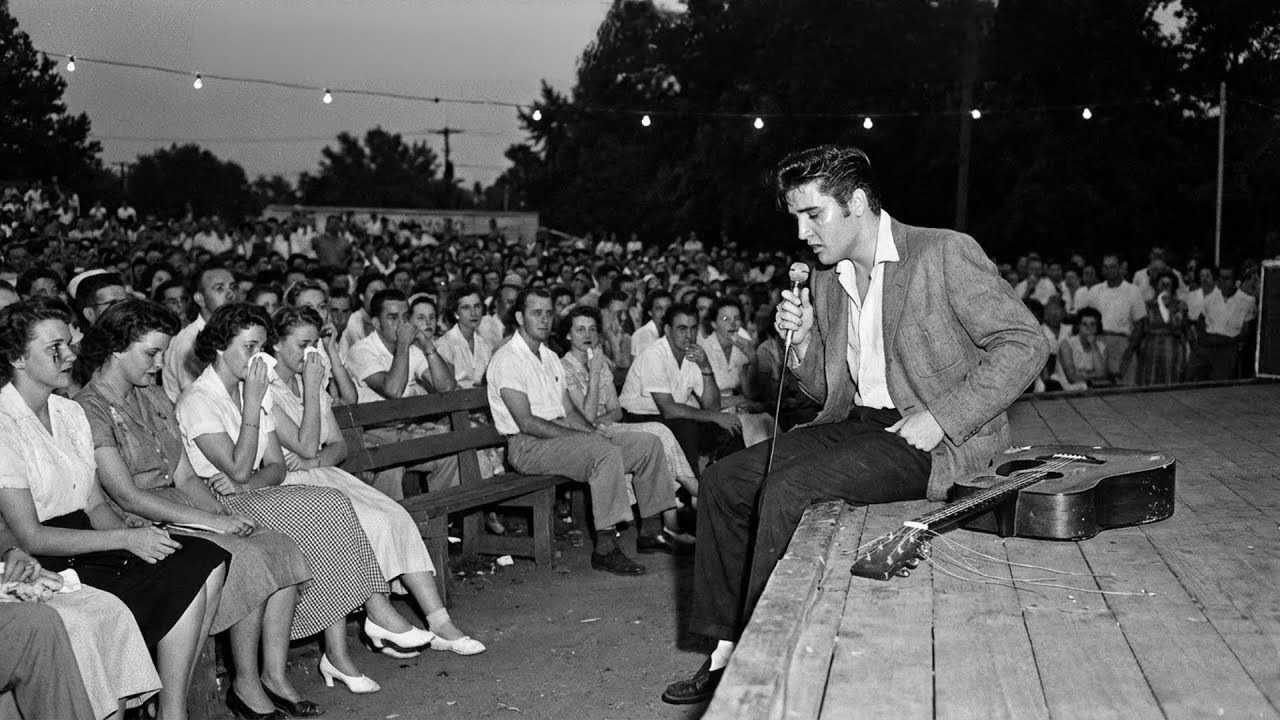

On September 23rd, 1955, at the Overton Park Shell in Memphis, 20-year-old Elvis Presley walked onto stage for what would become the most catastrophic performance of his entire career. In front of 2,500 hometown fans. Everything that Could go wrong went spectacularly, humiliatingly wrong.

His guitar strings snapped. His voice cracked on every high note. The sound system failed twice. And by the middle of his third song, half the audience was booing. But what happened in the final 10 minutes of that disastrous show would teach Elvis the most important lesson of his life about the power of vulnerability and create a moment so authentic and moving that the people who witnessed it still call it the most beautiful performance they ever saw.

But let me tell you exactly how everything fell apart that night. Because Elvis’s journey from complete failure to transcendent connection will show you that sometimes our greatest disasters become our most important discoveries about what it means to be truly human in front of others. September 1955 was supposed to be Elvis’s breakthrough moment.

He’d been performing for just over a year, had cut a few records with Sun Studio, and was starting to build a following around Memphis and the surrounding areas. The Overton Park Shell concert was his biggest booking yet, a hometown show that would prove he could handle a large audience and establish him as more than just a novelty act.

Elvis had been preparing for weeks. He’d practiced every song until he could perform them in his sleep, planned his stage movements, even bought a new outfit, a pink shirt and black pants that cost more than he usually spent on clothes in a month. This was going to be his moment to show Memphis that their local boy was ready for the big time.

But Elvis woke up that September morning feeling off. He’d barely slept the night before. His throat felt scratchy and his hands were shaking with nerves in a way they never had before. His girlfriend at the time, Dixie Lock, had tried to calm him down over breakfast. Elvis, you’ve done this dozens of times now. You know these songs better than anyone.

Not in front of 2,500 people, Dixie. Not with the whole music industry watching to see if I’m the real deal or just some flash in the pan. The pressure was getting to him in ways he hadn’t expected. Word had spread that talent scouts from Nashville would be in the audience along with music journalists and established performers who would be judging whether this young truck driver from Tupelo had what it took to make it in the music business.

By afternoon soundcheck, it was clear that nothing was going to go smoothly. The sound system at the Overton Park Shell was old and temperamental. Elvis’s microphone kept cutting out. The guitar amplifier was producing static, and the acoustics in the outdoor venue were challenging even for experienced performers. “Don’t worry about it,” said Scotty Moore, Elvis’s guitarist.

“We’ll make it work. We always do.” But Elvis could feel something different about this night. The confidence that usually carried him through performances felt fragile, replaced by a growing anxiety that made his stomach twist and his palms sweat. As the sun set and the audience filled the shell, Elvis stood backstage trying to calm his nerves.

Through the curtain, he could see the largest crowd he’d ever faced. Young people, older adults, families with children, all looking toward the stage with expectation. When the announcer introduced him, Elvis walked out to enthusiastic applause and cheers. But as soon as he strapped on his guitar and approached the microphone, he knew he was in trouble.

His first song was That’s All Right, the tune that had started his recording career. Elvis opened his mouth to sing, and his voice came out as a strangled croak. The weeks of nervous tension had tightened his throat, and the high notes that usually soared effortlessly became painful.

Obvious reaches that cracked and wavered. The audience noticed immediately. The cheering died down, replaced by confused murmurss. Elvis tried to recover, cleared his throat, and started the song again. This time, his voice held, but just as he was settling into the rhythm, his high E string snapped with a sharp ping that echoed through the sound system.

Scotty and basist Bill Black tried to cover for him, but Elvis was rattled. He fumbled with the broken string, his hands shaking as he tried to continue playing with five strings instead of six. The song limped to an awkward conclusion, and the applause was polite, but noticeably less enthusiastic. “Technical difficulties,” Elvis said into the microphone, trying to make light of the situation.

“Let me try another one.” His second song was Blue Moon of Kentucky, a number he’d performed confidently dozens of times. But as he launched into the opening, the sound system failed completely. His microphone went dead, the guitar amplifier cut out, and for 30 seconds, Elvis stood on stage in front of 2,500 people in complete silence.

Sound technicians scrambled to fix the equipment while Elvis stood frozen, unsure whether to keep playing his unplugged guitar or wait for the system to come back online. The audience began to grow restless. Some people started talking among themselves. Others began to leave. When the sound finally returned, Elvis was so flustered that he forgot the words to the second verse of a song he’d known for years.

He stumbled through improvised lyrics that made no sense. His voice still cracking on the high notes, his guitar playing tentative and uncertain. By the time he finished the second song, Elvis could hear actual booing from sections of the audience. Standing on that stage, listening to his hometown crowd express their disappointment.

Elvis felt something break inside him. This was supposed to be his big moment, his proof that he belonged on stage with professional entertainers. Instead, he was failing spectacularly in front of everyone who mattered. For a moment, he considered walking off stage. He could make up some excuse about being sick, blame the equipment problems, preserve what was left of his dignity.

The smart thing would be to cut his losses and try to rebuild his reputation at smaller venues. But as Elvis looked out at the audience, some still booing, others talking among themselves, many heading for the exits, he saw something that stopped him cold. In the front row, an elderly man was still watching intently, not with criticism or disappointment, but with what looked like compassion.

Next to him, a young mother was trying to quiet her restless child while still paying attention to the stage. And scattered throughout the shell were faces of people who hadn’t given up on him yet. They looked concerned, maybe even sorry for him, but they were still there, still listening, still hoping he might find his way back to the music they’d come to hear.

Elvis realized that this moment, this complete, humiliating failure, was teaching him something no successful performance ever could. He was seeing his audience not as judges or critics, but as human beings who understood what it felt like to struggle, to try something difficult and fall short. If you can feel Elvis’s moment of realization that failure can be more powerful than success, please hit that subscribe button.

What happened next would change how he understood the connection between performer and audience forever. And there are more incredible stories about finding strength and vulnerability coming. Instead of walking off stage, Elvis did something that surprised everyone, including himself. He sat down on the edge of the stage, letting his legs dangle like a child sitting on a fence, and spoke directly to the audience without the microphone.

“Folks,” he said, his voice carrying clearly in the sudden quiet. I reckon y’all can tell this isn’t going the way any of us hoped it would. A few people laughed, not mockingly, but with recognition of the obvious truth. I came out here tonight thinking I had to prove something to you, thinking I had to be perfect to earn your respect.

But sitting here looking at y’all, I’m realizing something. We’re all just people trying to make something beautiful together. And sometimes that means admitting when we’re scared or when things aren’t working out like we planned. Elvis stood up, walked back to the microphone, and made a decision that would change his approach to performing forever.

“I want to try something different,” he said. “Instead of trying to impress you with songs I’m supposed to sing perfectly, I want to sing something that means something to me, even if I mess it up, even if my voice cracks or I forget the words.” Because maybe that’s more honest than pretending to be something I’m not.

He started to sing Old Shep, a song about a boy and his dog that he’d learned from his mother when he was a child. It wasn’t one of his usual rock and roll numbers. Wasn’t something that would showcase his range or his energy. It was just a simple, sad, beautiful song about love and loss and growing up. Elvis sang it quietly, intimately, as if he were sitting on his front porch instead of standing on a stage.

His voice still cracked occasionally, but instead of trying to hide it, he let it happen. Let the emotions show through the imperfection. Something magical began to happen in the audience. People stopped talking, stopped leaving. They leaned forward, drawn in by the unexpected vulnerability of this young man who had stopped trying to be a star and started being human.

When Elvis finished Old Shep, the shell was completely quiet. Then slowly the applause began. Not the wild cheering of excited fans, but the deeper, more sustained appreciation of people who had just witnessed something real and unguarded. “Thank you,” Elvis said quietly. “That’s that’s who I really am, I guess.

Not the guy who was trying so hard to impress you earlier, but just someone who loves music and wants to share it with people who understand.” He sang two more songs, both slow and personal, both performed with the same undefended honesty. His voice still wasn’t perfect. His guitar playing was still tentative, but none of that mattered anymore.

He had found something more valuable than technical perfection. He had found authentic connection. When Elvis finally left the stage that night, he expected to face disappointed promoters and harsh reviews. Instead, he found something unexpected waiting for him backstage. People from the audience had gathered behind the venue, not to criticize or complain, but to thank him.

The elderly man from the front row approached first. “Son,” he said, “I’ve been to a lot of concerts in my 73 years, and I can tell you that what you did out there, admitting you were struggling and then singing from your heart anyway. That took more courage than any perfect performance ever could. A middle-aged woman with tears in her eyes added, “My husband died last year.

” And when you sang Old Shep, “It was the first time since his funeral that I felt like someone understood what grief actually feels like.” One by one, audience members shared similar sentiments. They hadn’t come expecting to see vulnerability or imperfection, but they’d witnessed something that perfect performances rarely provide.

the recognition that we’re all struggling with something and that sharing our struggles honestly can be more powerful than hiding them behind polished facades. That disastrous night at Overton Park Shell changed Elvis’s entire approach to performing. He learned that his greatest strength wasn’t his ability to execute flawless performances, but his willingness to be genuinely present with his audience, to let them see his humanity alongside his talent.

From that night forward, Elvis began incorporating more vulnerable moments into his shows. He’d talk to audiences between songs about his fears, his struggles, his gratitude. He’d acknowledge when things went wrong instead of trying to cover up mistakes. He learned to see technical difficulties not as disasters, but as opportunities to connect with people on a more human level.

The music critics who attended that night wrote reviews that focused not on Elvis’s vocal or instrumental abilities, but on his emotional courage. One journalist wrote, “Elvis Presley may not be the most technically accomplished performer on the circuit, but he has something more valuable, the ability to make 2,500 people feel less alone in the world.

” The recording industry scouts who had come to evaluate Elvis’s commercial potential left with a different kind of assessment. They realized they weren’t just looking at a singer, but at someone who could create genuine emotional experiences for audiences. Someone whose imperfections made him more relatable rather than less marketable.

Have you ever had a moment when everything went wrong, but that failure taught you something more valuable than success ever could have? A time when being vulnerable and honest connected you with people in ways that trying to be perfect never did. Tell us about those moments in the comments. Let’s celebrate the failures that became our greatest teachers.

If this story reminded you that authenticity is more powerful than perfection, make sure you’re subscribed for more incredible stories about finding strength through vulnerability. Hit that notification bell for stories about the moments when our greatest disasters become our most important discoveries. The most important thing Elvis learned that night wasn’t about performing or entertaining.

It was about the courage to be imperfect in front of others. He discovered that audiences don’t need their heroes to be flawless. They need them to be human, to struggle and fail and get back up again just like everyone else. Sometimes our worst performances become our best performances. Not because we execute them perfectly, but because we stop trying to be someone we’re not and start being exactly who we are.

Broken strings, cracked voices, and all. That September night, Elvis learned that the most beautiful music doesn’t come from perfection. It comes from the courage to sing your truth even when your voice isn’t working quite